Deutsch

Geschätzter Gast oder geschuldete Last? Zur fragilen Geschichte eines symbiotischen Verhältnisses

Wenn mitten in der Nacht ein großes Büro am Institut noch hell erleuchtet und mit eifriger Betriebsamkeit erfüllt ist, dann weiß man: Hier stellen die Studierenden des Heidelberger Jessup Moot Court Teams ihre Schriftsätze fertig. Es ist kein gewöhnliches Büro, denn die Wände sind mit zahlreichen Plaketten und gerahmten Urkunden geschmückt, mit denen frühere Teams für ihre Erfolge ausgezeichnet wurden. Die Geschichte hinter diesen Erfolgen und der Beitrag des Instituts soll im Folgenden ergründet werden.

Am Jessup Moot Court, den es zunächst vorzustellen gilt (I.), haben bereits 39 Heidelberger Teams teilgenommen (II.). Das Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (MPIL) hat zahlreiche dieser Teams intensiv unterstützt. Der Rückblick in die Erfolgsgeschichte bringt aber auch deren Fragilität ans Licht (III.). Dessen ungeachtet hat sich zwischen MPIL und Jessup ein symbiotisches Verhältnis herausgebildet (IV.), das für die Fortschreibung dieser gewinnbringenden Tradition zuversichtlich stimmt (V.).

I. Der Jessup

Der Jessup International Law Moot Court (kurz: „Jessup“) ist der völkerrechtliche Moot Court par excellence. Der größte und älteste Wettbewerb auf dem Gebiet des Völkerrechts wurde 1960 an der Harvard University ins Leben gerufen, seit 1968 wird er international ausgetragen, in der Kampagne 2024 mit über 600 Teams aus aller Welt. Universitäten dürfen je ein Team mit bis zu fünf Student:innen (Mooties) und mehreren Betreuer:innen (Coaches) entsenden. Bei den nationalen Vorentscheiden (National Rounds) qualifizieren sich die erfolgreichsten Teams für die „International Rounds“, die sodann in Washington, D.C. ausgetragen werden. Der Jessup schult somit nicht nur Generationen von Studierenden im Völkerrecht, sondern leistet auch einen Beitrag zum internationalen Austausch.

Kern des Wettbewerbs ist die Simulation eines streitigen Verfahrens zweier Staaten vor dem Internationalen Gerichtshof, dem einst der Namenspate, der US-amerikanische Völkerrechtler und Diplomat Philip Caryl Jessup, als Richter angehörte. Der zur Bearbeitung gestellte fiktive Streitfall wirft dabei stets brisante völkerrechtliche Fragen auf. Jedes Team erarbeitet zunächst Schriftsätze (Memorials) für die Kläger- und Beklagtenseite und trägt die dabei entwickelten Argumente sodann in mündlichen Plädoyers (Pleadings) gegen andere Teams vor. Dabei spielen die Judges (typischerweise Praktiker:innen und Professor:innen des Völkerrechts) eine entscheidende Rolle; sie bewerten die Memorials und Pleadings. Während der Pleadings stellen sie zahlreiche Fragen zum Sachverhalt und zur rechtlichen Argumentation, die die nacheinander plädierenden Mooties jeweils allein und möglichst überzeugend aus dem Stegreif beantworten müssen. So entsteht ein intensiver, juristisch anspruchsvoller Austausch.

II. Die Heidelberger Jessup-Teams

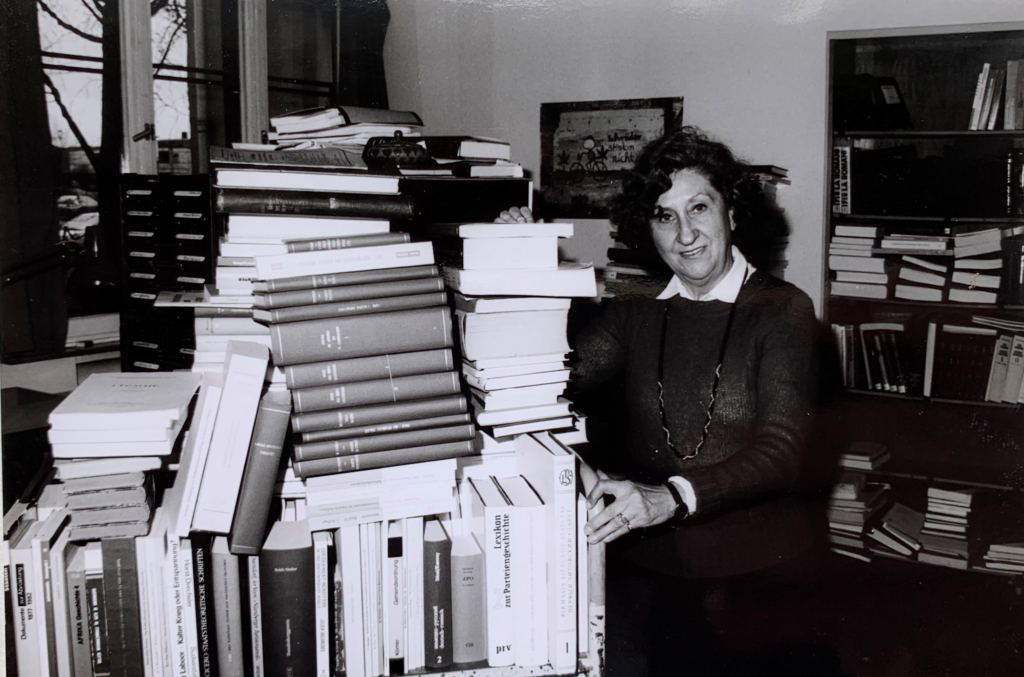

Das Jessup-Team 2008: David Schweizer, Daniel Scherr, Vasiliki Koligliati, Benedikt Walker, Natalia Jevglevskaja, Katerina Vagia, Verena Kling und Ingo Venzke (Foto: MPIL)

Jessup-Teams treten in der Regel im Namen ihrer Universität an. Es ist ein Wettbewerb für Studierende, die auszubilden universitäre Aufgabe ist. Seit Langem ist es in Heidelberg aber primär das MPIL, das die Jessup-Teams betreut. Ein Blick in die Tätigkeitsberichte des MPIL weist dies erstmals für das Wintersemester 1990/91 nach. Aber gab es bereits vorher Heidelberger Jessup-Teams? Wer betreute sie? Weder am MPIL noch bei der Juristischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität ließen sich dazu Hinweise finden. Auch aus den Erinnerungen befragter Zeitzeug:innen ergab sich kein klares Bild. Hinweise finden sich schließlich aber in den Aufzeichnungen der International Law Students Association (ILSA), die den Jessup verantwortet. Nach den Unterlagen von ILSA nahm erstmals 1985 ein Heidelberger Team teil, seit 1987 ist ununterbrochen für jedes Jahr ein Heidelberger Team verzeichnet. Beim Jessup 2024 trat somit das 39. Heidelberger Team an. Die Teams wurden bei ILSA meist im Namen der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität angemeldet, nur 2003 und 2009 im Namen des MPIL. Rückschlüsse auf die Betreuung lässt das aber nicht zu, weitere Tätigkeitsberichte des MPIL weisen nämlich klar auf die ununterbrochene Mitwirkung des Instituts seit 1990/91 hin. Indizien für eine Mitwirkung der Juristischen Fakultät an der Betreuung der Teams ließen sich lediglich für das Jahr 1993 finden.

Die fast vier Jahrzehnte Heidelberger Jessup-Tradition krönt mancher Erfolg: Bislang qualifizierten sich elf Heidelberger Teams für die Teilnahme an den International Rounds, zweimal (1997, 2000) waren sie unter den 16 besten Teams weltweit. Bei den German National Rounds erreichten fünf Heidelberger Teams einen ersten, fünf einen zweiten und sechs Teams einen dritten Platz (zuletzt 2023). Hinzu kommen unzählige Auszeichnungen für Memorials und individuelle Leistungen in den Pleadings. Auch eine Auszeichnung mit dem Spirit of the Jessup Award der German National Rounds – verliehen an das Team, das den Geist des Wettbewerbs am besten verkörpert – konnte Heidelberg 2018 erlangen.

III. Fragilität: Der Wandel der Unterstützung durch das MPIL

Das Jessup-Team 2023 in Den Haag. Hintere Reihe, vlnr: Lukas Hemmje (Coach), Jakob Mühlfelder (Coach), Jasper Kurth, Leo Volkhardt. Vordere Reihe, vlnr: Sophie Raab (Coach), Laura Schwamm, Bozheng Chen, Barbara Hauer

Ohne die Mitwirkung des MPIL wären diese Erfolge undenkbar. Als Gästen des Instituts wird den Teams vielfältigste Unterstützung zuteil. Sehr hilfreich ist zunächst, dass den Teams – wie eingangs erwähnt – ein eigenes Büro am Institut zur Verfügung steht. Für die Recherchen zu den streitigen völkerrechtlichen Fragen ist der Zugriff auf die Ressourcen der Bibliothek unentbehrlich, der von freundlicher Unterstützung seitens der Mitarbeiter:innen von Ausleihe, Fernleihe, Buchbestellung, Zeitschriftenabteilung und der UN-Depotbibliothek begleitet wird. Zeitweise wurden die Schriftsätze der Jessup Teams sogar mit eigener Signatur in die Bibliothek aufgenommen (VR: I G: 41). Hinzu kommen dutzende Probe-Pleadings mit Wissenschaftler:innen des Instituts, in denen die Mooties ihre Argumente und Kenntnisse auf den Prüfstand stellen können. Über die Unterstützung Heidelberger Teams hinaus hat das MPIL bereits sechs Mal (1996, 2001, 2007, 2013, 2015, 2022) die deutschen National Rounds des Jessup ausgerichtet – zweimal davon recht kurzfristig, wenn keine Universität die Ausrichtung übernehmen wollte.

Neben dem MPIL kommt der damit eng verbundenen Heidelberger Gesellschaft für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht eine besondere Bedeutung zu. Die Heidelberger Gesellschaft finanziert Heidelberger Teams nicht nur regelmäßig die beträchtliche Anmeldegebühr für den Jessup, sondern ermöglichte zahllosen Heidelberger Jessup-Generationen auch die große Pilgerreise der Völkerrechtsfans – eine Studienreise nach Den Haag. Dort gewannen die Teams inspirierende Einblicke in den Internationalen Gerichtshofs, den Internationalen Strafgerichtshof, die deutsche Botschaft und andere Wirkstätten des Völkerrechts.

Am wichtigsten ist wohl aber die Betreuung durch die vom Institut angestellten Coaches, die regelmäßig von besonderem persönlichem Engagement gekennzeichnet ist. An dieser Stelle zeigt sich auch die größte Veränderung der Jessup-Betreuung am MPIL, die schematisierend als Wandel von einem direktoralen Ansatz zu einem gemeinschaftlichen Ansatz beschrieben werden kann. In den 90er Jahren gingen alle wichtigen Schritte zum Zustandekommen der Jessup-Teams vom Direktorium aus: Ein Direktor wies ein oder zwei Wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiter:innen an, das Team zu betreuen, unterstützt von ein oder zwei Mooties des Vorjahres (angestellt als studentische Hilfskräfte). Es war auch das Direktorium, das die neuen Mooties gezielt in Völkerrechtsvorlesungen und -seminaren ansprach und auswählte.

Seit mehreren Jahren geht die Initiative für die Aufstellung neuer Teams hingegen stärker von der Gemeinschaft ehemaliger Heidelberger Jessup Mooties und Coaches (Jessup Community) aus. Die Mooties des Vorjahres ziehen durch die Vorlesungen und veranstalten Info-Abende, um neue Studierende für den Wettbewerb zu gewinnen. Es sind die ehemaligen Coaches, die sich auf die Suche nach neuen Coaches machen und den Wunsch nach entsprechenden Stellen am MPIL an das Direktorium herantragen. Jeder neuen Jessup-Runde geht dabei ein Bangen voraus, ob und wie viele neue Coaches sich finden lassen und wie viele Stellen am MPIL geschaffen werden können. Auf diesem Wege ließen sich zum Beispiel 2019 und 2020 nur je zwei ehemalige Mooties finden, die die Betreuung übernahmen – ein Engagement mit nicht unerheblicher Belastung neben ihrem Studium. Auch die Auswahl der neuen Mooties liegt seit vielen Jahren in der Hand der Heidelberger Jessup Community, die die Auswahlgespräche organisiert und durchführt.

Dieser Wandel hin zu einem gemeinschaftlichen Ansatz bringt einen ganz erheblichen Vorteil mit sich: Die Verantwortung, die damit bei den ehemaligen Mooties und Coaches liegt, befördert das besondere Gemeinschaftsgefühl der Heidelberger Jessup Community. Es zeugt vom großen Vertrauen des Instituts in diese Community, dass ihr so viel Gestaltungsfreiheit im gesamten Prozess der Auswahl und Betreuung der Teams gewährt wird. Die neuen Coaches können auf das tradierte Wissen und die Erfahrungen vorheriger Generationen zurückgreifen, haben darüber hinaus aber auch die Freiheit, neue Modelle und Methoden bei der Teambetreuung zu verwirklichen.

Als Kehrseite folgt für gegenwärtige und künftige Heidelberger Jessup-Generationen daraus zugleich ein Appell zum Engagement und zur Eigeninitiative. Ohne direktorale Initiative und Federführung ist die Jessup-Betreuung am MPIL keine institutionell garantierte Selbstverständlichkeit. Dies zeigt auch das Beispiel des Concours Européen des Droits de l‘Homme René Cassin, bei dem ein Verfahren vor dem Europäischen Gerichtshof für Menschenrechte in Straßburg simuliert wird. Das Institut hat mindestens seit 1993 Heidelberg René Cassin Teams unterstützt, im Jahr 1998 auch einen Sieg in Straßburg erzielt. Seit 2004 aber nehmen keine Heidelberger Teams mehr am Concours René Cassin teil. Eine einst erfolgreiche Tradition kann eben auch enden.

Für eine Fortschreibung der Heidelberger Jessup-Tradition ist es daher unabdingbar, dass ehemalige Mooties Verantwortung übernehmen für künftige Jessup-Generationen und die (in der Regel sehr großzügige) Unterstützung des MPIL auch aktiv einfordern. Mit dem Wandel des Betreuungsansatzes ging in der Regel zwar nicht einher, dass das Institut letztlich weniger Ressourcen für die Jessup-Betreuung eingesetzt hätte als unter direktoraler Leitung. Um diese Ressourcen muss von den ehemaligen und neuen Coaches aber beharrlich geworben werden. Dies ist nicht immer ganz leicht, warten nach der Teilnahme am Jessup oder der Betreuung eines Teams doch immer die nächsten zu erbringenden Studienleistungen, das Staatsexamen oder die Weiterarbeit an der Dissertation. Das dennoch ununterbrochene Fortbestehen der Heidelberger Jessup Tradition deutet an, wie viele Stunden freiwilligem Engagements – in Abendstunden, an Wochenenden und Feiertagen – die Heidelberger Jessup Community investiert hat.

IV. Symbiose: Beiderseitiger Nutzen für MPIL und Jessup

Einerseits lässt sich also ein Wandel der Unterstützung Heidelberger Jessup-Teams durch das MPIL von einem direktoralen hin zu einem gemeinschaftlichen Ansatz beobachten, mit dem eine gewisse Fragilität der Zukunft des Jessup am MPIL einhergeht. Andererseits suggerieren die langjährig ununterbrochene Jessup-Tradition und der letztlich mehr oder weniger unverändert bleibende Ressourceneinsatz des MPIL für die Jessup-Bereuung Verlässlichkeit und Kontinuität. Dieser ambivalente Befund – Kontinuität trotz Fragilität – lässt sich durch das symbiotische Verhältnis von Jessup und MPIL erklären, das sich in Heidelberg herausgebildet hat. Vordergründig profitieren die Jessup-Teams von der ressourcenintensiven Betreuung durch das MPIL. Zugleich, und darin liegt das Symbiotische, profitiert aber auch das MPIL vom Jessup.

Der Jessup bringt für Mooties, Coaches und das MPIL erheblichen Mehrwert. Für die Mooties bedeutet die Jessup-Teilnahme eine einmalige und großartige Chance. In der Regel bietet das Studium der Rechtswissenschaft in Deutschland kaum Gelegenheit zur Teamarbeit, nur verschwindend wenige internationale Bezüge, kaum Vermittlung von fachspezifischen Fremdsprachenkenntnissen, ein schlechtes Betreuungsverhältnis, wenig Anreize zur eigenständigen Entwicklung juristischer Argumente und erst recht kaum einen Rahmen, diese mündlich vorzutragen. All dies aber bietet der Jessup, in einem arbeits- und lernintensiven Semester. Neben einem herausragenden Verständnis der Grundlagen des Völkerrechts entwickeln die Mooties bei der Erstellung der Memorials exzellente Recherchefähigkeiten und lernen, zu den aufgeworfenen, komplexen Rechtsfragen in konziser und klarer Sprache Stellung zu nehmen. Wer später in anwaltlichen Schriftsätzen interessenorientiert, juristisch seriös und stichhaltig argumentieren will, wird von der mehrmonatigen, sorgfältigen Erstellung von Memorials erheblich profitieren. Die strenge Wortbegrenzung zwingt dabei dazu, die besten Argumente auszuwählen und auf den Punkt zu bringen. Die Vorbereitung der Pleadings kommt einem intensiven Englisch- und Rhetorikkurs gleich, in dem die Mooties lernen, spontan die kritischsten Fragen der Judges professionell zu parieren. Neben Legal English als Arbeitssprache, Beschäftigung mit dem Völkerrecht und Studienreise nach Den Haag bringt – nach Monaten harter Arbeit und mit etwas Glück – schließlich auch die Teilnahme an den International Rounds in Washington D.C. den Teams wertvolle internationale Erfahrungen. Zugleich zwingt die intensive Zusammenarbeit von Mooties und Coaches alle zur Weiterentwicklung ihrer Teamfähigkeiten. Zeitdruck und intensive Arbeit schweißen das Team zusammen. Coaches können erste Führungserfahrungen sammeln, die auch für eine weitere wissenschaftliche Karriere wichtig sind. Etliche Ehemalige blicken mit Freude auf diese Zeit zurück, die neben dem Erwerb juristischer Fähigkeiten auch langanhaltende Freundschaften stiftet. Dem Charakter des Jessup als Wettbewerb entsprechend, kann nicht jedes Team siegen. Gewonnen sind für alle Mooties aber die großartigen Lernchancen, die sich über die Monate der Vorbereitung hinweg bieten.

Diesen erheblichen Vorteilen stehen auch berechtigte Einwände gegenüber. Eine sinnvolle Betreuung der Jessup-Teams verlangt erhebliche finanzielle und personelle Ressourcen. Die Zahl der Mooties ist von ILSA auf fünf beschränkt, das Privileg der Teilnahme kann daher nur wenigen Studierenden gewährt werden. Zudem gehört die Ausbildung Studierender nicht zur Kernaufgabe eines der Grundlagen- und Spitzenforschung gewidmeten Instituts. Die als zuständig anzusehende Juristische Fakultät hat zur Betreuung der Heidelberger Jessup-Teams bislang allerdings kaum Ressourcen beigetragen.

Der Jessup hat aber auch erheblichen Nutzen für das MPIL. Mooties lernen als Gäste das Institut seine Abläufe und Strukturen kennen. Sie durchsuchen wissenschaftliche Quellen nach juristischen Argumenten und entwickeln dabei einen kritischen Blick auf die Völkerrechtswissenschaft und ihre Methodik. Mit ihrer exzellenten Befähigung zur eigenständigen Recherche völkerrechtlicher Fragen sind sie prädestiniert, dem Institut nach dem Jessup als Hilfskräfte verbunden zu bleiben – so ist es gängige Praxis. Manchen Mootie führte dieser Pfad sodann auch zu einer Promotion und wissenschaftlichen Mitarbeit am MPIL. Der Jessup hilft dem MPIL also, engagierte Studierende der Fakultät an das Institut heranzuführen und mit der Völkerrechtswissenschaft vertraut zu machen. Das MPIL gewinnt durch den Jessup erheblich an Sichtbarkeit an der Universität, durch die German National Rounds und durch Erfolge in den International Rounds wirkt diese Sichtbarkeit weit über Heidelberg hinaus. Zugleich kann das Direktorium die Studierenden zunächst als Gäste kennenlernen, bevor über eine Anstellung als Hilfskraft oder Mitarbeiterin zu entscheiden ist.

V. Rückblick und Ausblick

Die Geschichte des Jessup Moot Court am MPIL lässt sich daher unbedingt als Erfolgsgeschichte erzählen. In fast vier Jahrzehnten hat das Jessup-Fieber zahlreiche Heidelberger Mooties und Coaches angesteckt, die Teilnahme hat ihnen eine einzigartig wertvolle Lernerfahrung geboten. Von dieser Begeisterung junger Menschen für das Völkerrecht profitiert auch das MPIL. Ohne die oft sehr intensive Betreuung wäre dies nicht möglich gewesen. Das Erfolgsnarrativ sollte aber nicht den Blick darauf verschließen, dass die Kontinuität der Jessup-Tradition am MPIL oftmals auf der Kippe stand.

Wie kann daher für künftige Jessup-Generationen deren Fortschreibung garantiert werden? Dafür braucht es sowohl ein Engagement der Heidelberger Jessup Community, neue Teams auf vielfältige Weise zu unterstützen, als auch eine intensive institutionelle Unterstützung durch das MPIL und die Heidelberger Gesellschaft. Das Verhältnis dieser Triebkräfte der Heidelberger Jessup Tradition gilt es jedes Jahr neu auszuloten. Die Fortschreibung der Heidelberger Jessup Geschichte hängt am Zusammenspiel dieser Kräfte, die notwendige, für sich allein aber nicht hinreichende Bedingungen zu diesem Ende sind. Aus dieser Diagnose folgt, dass der Jessup in Heidelberg sowohl aus Perspektive des MPIL als auch aus Sicht der Jessup Community nicht als Selbstverständlichkeit angesehen werden kann. Umso beeindruckender, dass es ihn seit fast 40 Jahren in Heidelberg gibt.

Hinweis zur Quellenlage und Transparenz: Mein Beitrag speist sich aus eigener Anschauung (als Heidelberger Jessup Mootie 2018, Coach 2019 und 2022), aus Gesprächen und Schriftverkehr mit anderen ehemaligen Mooties, Coaches und mit weiteren Beteiligten am Institut sowie aus Erfahrungsberichten der Heidelberger Teams (ab 2006), Tätigkeitsberichten des Instituts, Dokumenten der Heidelberger Gesellschaft, Archivunterlagen von Prof. Wolfrum, Ordner III der Institutschronik und Aufzeichnungen der International Law Students Association (ILSA). Sichere Kenntnisse über das Abschneiden Heidelberger Teams bei den National und International Rounds liegen ab 1997 vor.

English

Valued Guest or Burden Owed? On the Fragile History of a Symbiotic Relationship

When in the middle of the night a spacious office at the institute is still brightly lit and filled with bustling activity, there is no doubt: This is where the students of the Heidelberg Jessup Moot Court team finalise their memorials. It is no ordinary office, as the walls are decorated with numerous plaquettes and framed certificates honouring previous teams for their successes. Delving into the story behind these successes and the Institute’s contribution to them is the purpose of this blogposts.

It begins by introducing the Jessup Moot Court (I.) before exploring the participation of 38 Heidelberg teams (II.). The Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (MPIL) has extensively supported many of these teams. However, a retrospective on this success story also reveals its fragility (III.). Nevertheless, a symbiotic relationship has emerged between MPIL and Jessup (IV.), instilling confidence in the continuation of this tradition (V.).

I. The Jessup

The Jessup Team 2008: David Schweizer, Daniel Scherr, Vasiliki Koligliati, Benedikt Walker, Natalia Jevglevskaja, Katerina Vagia, Verena Kling und Ingo Venzke (photo: MPIL)

The Jessup is the international law moot court par excellence. Initiated at Harvard University in 1960, it is the oldest and largest competition in the field of international law. Since 1968, it has been held internationally, in 2024 with over 600 teams participating from around the world. Each university may send one team of up to five students (Mooties) and several team advisers (Coaches) to the competition. The most successful teams in National Rounds qualify for the International Rounds held in Washington, D.C. Thereby, the Jessup not only educates generations of students in international law but also contributes to international exchange.

At the core of the competition is the simulation of contentious proceedings between two states before the International Court of Justice, where eponym Philip Caryl Jessup – US-American diplomat and international lawyer – once served as a judge. The fictitious case always raises challenging contemporary international legal issues. Each team prepares written submissions (Memorials) for the applicant and respondent state and presents their arguments in oral pleadings against other teams. The Judges (typically practitioners and professors of international law) play a decisive role; they evaluate the memorials and pleadings, thus determining the winning team. During the pleadings, they also ask numerous questions to which the Mooties must reply spontaneously and persuasively. This creates an intense, legally challenging discussion.

II. Heidelberg’s Jessup Teams

Jessup teams usually compete on behalf of their university. It is a competition for students, whose education is a university task. However, Heidelberg’s Jessup teams have long been primarily supported by the MPIL. According to MPIL’s annual activity reports, the institute’s involvement with Jessup dates back to the 1990/91 winter semester. No evidence could be found at MPIL or at the Faculty of Law at Ruprecht-Karls-University on any Heidelberg Jessup teams participating before that. The recollections of contemporary witnesses do not provide a clear picture either. However, records from the International Law Students Association (ILSA), responsible for organizing the Jessup, reveal that a Heidelberg team first participated in 1985, and that there has been a Heidelberg team every year since 1987. Hence, the team participating in Jessup 2024 will be the 39th Heidelberg team. Teams were usually registered with ILSA in the name of Ruprecht-Karls-University, except in 2003 and 2009 when they were registered as MPIL teams. However, this does not provide insight into coaching responsibilities, as MPIL’s activity reports clearly indicate continuous involvement of the institute since 1990/91. Evidence of the Law Faculty supporting Heidelberg’s Jessup teams could only be found for the year 1993.

The nearly four decades of Heidelberg Jessup tradition boast several successes. Eleven Heidelberg teams qualified for the International Rounds, and twice (1997, 2000) they were among the top 16 teams worldwide. In German National Rounds, five Heidelberg teams secured first place, five second place, and six third place (most recently in 2023). Additionally, numerous awards for memorials and individual achievements in pleadings have been earned. Heidelberg also received the Spirit of the Jessup Award at the German National Rounds in 2018, bestowed upon the team that best embodies the spirit of the competition.

III. Fragility: The Evolution of MPIL Support

The Jessup team 2023 in The Hague. Back row, from left to right: Lukas Hemmje (coach), Jakob Mühlfelder (coach), Jasper Kurth, Leo Volkhardt. Front row, from left to right: Sophie Raab (coach), Laura Schwamm, Bozheng Chen, Barbara Hauer

Without MPIL’s involvement, these achievements would be unthinkable. As guests of the institute, teams receive support in various forms. Having an office at the institute is particularly helpful, as it provides access to the library’s resources for research on contentious international legal issues. This is complemented by the friendly assistance of library staff in borrowing, interlibrary loans, book orders, journals section, and the UN Depository Library. At times, the Jessup teams’ Memorials were even archived in the Institute’s library with their own signature (VR: I G: 41). Moreover, there are numerous practice pleadings with MPIL’s staff researchers, allowing the Mooties to test their arguments and knowledge. Beyond supporting Heidelberg teams, MPIL has hosted the German National Rounds of the Jessup six times (1996, 2001, 2007, 2013, 2015, 2022) – two of which were organized at short notice when no university volunteered.

Apart from MPIL, the Heidelberger Gesellschaft für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (Heidelberg Society for Comparative Public Law and International Law) plays a crucial role. The society regularly pays the substantial registration fees for the Jessup and enables countless Heidelberg Jessup generations to embark on the great pilgrimage of international law – a study trip to The Hague. There, teams gain inspiring insights in the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court, the German Embassy, and other venues of international law.

However, the most critical element is the guidance provided by coaches employed by the institute. This aspect is where the most significant change in Jessup support at MPIL becomes evident, which can roughly be characterizes as a shift from a directorial approach to a communal approach. In the 1990s, all essential steps for forming Jessup teams were initiated by the directors: a director assigned one or two research assistants to coach the team, supported by one or two Mooties from the previous year (employed as student research assistants). The directors also used their international law lectures and seminars to approach students and invite them to join the team.

In contrast, for several years now, the initiative for forming new teams has increasingly come from the community of former Heidelberg Jessup Mooties and coaches (the Jessup Community). The previous year’s Mooties advertise the Jessup in lectures and organize information evenings to recruit new students for the competition. Former coaches actively seek out new coaches and convey the desire for corresponding jobs at MPIL to the directorate. Each new Jessup round is preceded by uncertainty about how many new coaches can be found and how many of them can be employed at MPIL. In 2019 and 2020, for example, only two former Mooties could be found to take on coaching responsibilities – a considerable commitment alongside their studies. The selection of new Mooties has also been in the hands of the Heidelberg Jessup Community for many years, organizing and conducting the selection interviews.

This shift towards a communal approach brings a significant advantage: the responsibility placed on former Mooties and coaches fosters a strong communal sense within the Heidelberg Jessup Community. Granting this community considerable freedom in the entire process of selecting and supervising teams is a sign of great trust. New coaches can draw on the traditional knowledge and experiences of previous generations while also having the freedom to implement new models and methods in team supervision.

As a flip side, this presents a call for initiative and engagement to current and future Heidelberg Jessup generations. Without directorial initiative and leadership, Jessup support at MPIL is not institutionally guaranteed. This is also illustrated by the example of the Concours Européen des Droits de l‘Homme René Cassin, a moot court simulating proceedings before the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. At least since 1993, the institute supported René Cassin Teams, winning the competition in the 1998 edition. However, after 2004, Heidelberg did not participate in the René Cassin anymore. Even a successful tradition may come to an end.

Against that background, ensuring the continuation of Heidelberg’s Jessup tradition requires former Mooties to take responsibility for future Jessup generations and actively call for the (generally very generous) MPIL support. The shift from a directorial approach to a communal approach only occasionally translated into the institute ultimately using fewer resources for Jessup coaching than under the directorial approach. However, these resources must be persistently solicited by former and new coaches. This is not always easy, given that after participating in the Jessup or supervising a team, the next academic achievements, the state examination or further work on the dissertation always await. The nonetheless continuous existence of Heidelberg’s Jessup tradition indicates how many hours Heidelberg’s Jessup Community has voluntarily invested – during evenings, weekends, and holidays.

IV. Symbiosis: Mutual Benefits for MPIL and Jessup

Crowned with success. Awards in the MPIL’s Jessup office (Photo: MPIL)

Thus, on one hand, a shift can be observed in MPIL’s support for Heidelberg Jessup teams from a directorial to a communal approach, bringing about a certain fragility in the future of Jessup at MPIL. On the other hand, the long-standing, uninterrupted Jessup tradition and the relatively unchanged resource allocation by MPIL for Jessup support suggest reliability and continuity. This ambivalent finding – persistence despite fragility – can be explained by the symbiotic relationship that has developed between Jessup and MPIL in Heidelberg. Evidently, Jessup teams greatly benefit from the resource-intensive support provided by MPIL. Simultaneously, and less obviously, MPIL also benefits from Jessup. Herein lies the symbiotic nature of the relationship between Jessup and MPIL.

For Mooties, coaches, and MPIL, the Jessup has a significant added value. For Mooties, Jessup participation is an outstanding opportunity. Typically, legal studies in Germany offer few chances for teamwork, minimal international elements, hardly any subject-specific language proficiency training, a poor student-to-supervisor ratio, limited incentives for independent development of legal arguments, and certainly no framework for presenting them orally. The Jessup provides all of these in an intensive semester of working and learning. In addition to an excellent understanding of the foundations of international law, Mooties develop sophisticated research skills while drafting memorials, and they learn to articulate clear and concise responses to complex legal questions. Anyone who later wants to argue in an interest-orientated, legally serious and cogent manner in legal briefs will benefit considerably from the meticulous preparation of memorials over several months. The strict word limit compels Mooties to select the best arguments and present them succinctly. The preparation of pleadings resembles an intensive English and rhetoric training, where Mooties learn to professionally respond to the judges’ most critical questions spontaneously. Beyond Legal English as a working language, engagement with international law, and a study trip to The Hague, participation in the International Rounds in Washington, D.C., after months of hard work and a bit of luck, provides teams with valuable international experiences. Simultaneously, the intense collaboration between Mooties and coaches forces everyone to further develop their teamwork skills. Time pressure and intensive work unite the team, while coaches gain initial leadership experiences crucial for further academic careers. Many alumni fondly look back on this time, which not only imparts legal skills but also fosters enduring friendships. As is in the nature of a competition, not every team can win the Jessup. However, all Mooties gain tremendous learning opportunities over the months of preparation.

These substantial benefits are countered by valid objections. Meaningful support for Jessup teams demands significant financial and human resources. ILSA restricts the number of Mooties to five, limiting the privilege of participation to only a few students each year. Moreover, educating students is not a core task of an institute dedicated to foundational and top-level research. However, the responsible Faculty of Law has, thus far, contributed hardly any resources to support Heidelberg’s Jessup teams.

The MPIL also benefits considerably from the Jessup. Mooties, as guests, familiarize themselves with the institute’s processes and structures. They research sources for legal arguments, developing a critical view of international law and its methodology. With their excellent ability to independently research international legal questions, they are well-suited to remain connected to the institute as student research assistants after the Jessup – indeed a common practice. For some Mooties, this path has led to pursuing a doctoral degree at MPIL. Therefore, the Jessup helps MPIL introduce dedicated law students to the institute and acquaint them with the study of international law. MPIL gains significant visibility at the university through the Jessup, and the German National Rounds and International Rounds extend this visibility far beyond Heidelberg. Meanwhile, the directorate can get to know the students as guests before employing them as researchers or assistants.

V. Retrospect and Outlook

The history of the Jessup Moot Court at MPIL can certainly be told as a success story. Over nearly four decades, the Jessup fever has infected numerous Heidelberg Mooties and coaches, providing them with a uniquely valuable learning experience. The MPIL has benefited from this enthusiasm of young people for international law, which would not have been possible without the often very intense support. This narrative of success, however, should not veil the fact that the continuity of MPIL’s Jessup tradition was often hanging by a thread.

How can the continuation of Jessup for future generations be guaranteed? This requires both the commitment of the Heidelberg Jessup Community to support new teams in diverse ways, and intensive institutional support from MPIL and the Heidelberg Society. The relationship between these driving forces of the Heidelberg Jessup tradition must be re-evaluated every year. The continuation of the Heidelberg Jessup history depends on the interplay of these forces, which are necessary but not sufficient conditions for this end. From this diagnosis, it follows that Jessup in Heidelberg cannot be considered a given, both from the perspective of MPIL and the Jessup Community. It is all the more impressive that there have been Heidelberg Jessup teams for almost 40 years now.

Note on sources and transparency: My contribution is based on personal experience (as a Heidelberg Jessup Mootie in 2018, coach in 2019 and 2022), conversations and correspondence with other former Mooties, coaches, and other stakeholders at the institute, as well as reports from Heidelberg teams (from 2006 onwards), activity reports from the institute, documents from the Heidelberg Society, archive materials from Prof. Wolfrum, Folder III of the institute’s chronicle, and records from the International Law Students Association (ILSA). Reliable knowledge about the performance of Heidelberg teams in National and International Rounds is available from 1997 onwards.

Felix Herbert ist wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am MPIL.

Felix Herbert is Research Fellow at the MPIL.