Im Sommersemester 1966 veranstaltete die Universität Heidelberg eine Studium-Genereale-Reihe zum Thema „Wissenschaft und Nationalsozialismus“. Zwei der insgesamt fünf Vorträge wurden von Hermann Mosler übernommen. Seine quasi am Vorabend der Studentenbewegung gehaltenen Vorlesungen über „Staatsrechtslehre und Nationalsozialismus“ zählen zu den wenigen öffentlichen Auseinandersetzungen des Völkerrechtlers mit dem „Dritten Reich“. Sie sind für Moslers Verhältnisse sehr direkt und nahezu persönlich formuliert. Mosler ist deutlich darum bemüht, den Studierenden ein umfassendes Bild von der nationalsozialistischen Staatslehre und ihren Ursprüngen sowie von den Arbeits- und Lebensbedingungen unter der Diktatur zu vermitteln: „Ich gehöre zu einem Jahrgang [1912], der im Jahre 1933 noch nicht handeln konnte, wohl aber urteilsfähig war.“[1] Mosler führt aus, er habe sich als Student, Doktorand und junger Wissenschaftler „zu jeder Phase eine Meinung gebildet. Manches sehe ich heute anders, teils deutlicher, teils weniger deutlich als ich das zu wissen glaubte.“

Detailliert schildert Mosler die Situation Deutschlands und der Staatsrechtswissenschaft in der Endphase der Weimarer Republik, führt die Reaktion seines Faches auf die „Machtergreifung“ aus, schildert den Ausbau des „totalen Staates“ und die Aushöhlung des Rechtsstaates. Mosler scheut sich nicht, eine klare Haltung zu bedeutenden ideologischen Akteuren der NS-Rechtswissenschaft wie Carl Schmitt, Reinhard Höhn oder auch seinem Fakultätskollegen Ernst Forsthoff zu beziehen und ihren Beitrag zur Legitimierung des NS-Regimes zu erörtern.

Mosler verweist aber auch darauf, dass sich nicht jeder Jurist blind auf den NS-Staat eingelassen habe, dass es auch mutige Wissenschaftler gegeben habe, die offen Widerspruch geübt hatten. Als Gewährsmann aus seinem Fach führt er seinen Bonner Mit-Doktoranden Rudolf Timmermans an, der in seiner 1936 erschienenen Dissertation deutliche Kritik am Führerstaat geäußert hatte und dessen Arbeit daraufhin von der Gestapo beschlagnahmt worden war; der Autor selbst hatte ins Ausland fliehen müssen, wo er den Krieg nicht überlebte.[2] Ein anderer Name, der insbesondere mit Blick auf eines der Vorlesungsdaten, den 20. Juli 1966, erwartbar gewesen wäre, fällt indes nicht: Berthold von Stauffenberg. Anders als der völlig unbekannte Timmermans war Stauffenberg für Mosler kein Anknüpfungspunkt für eine Rehabilitierung der Völkerrechtswissenschaft – trotz dessen Beteiligung am Widerstand des 20. Juli 1944. Teile der neueren völkerrechtshistorischen Forschung sehen in Stauffenberg indes eine Lichtgestalt der eigenen Disziplin im „Dritten Reich“ – einen aktiven Verfechter des Rechtstaates, der Völkergemeinschaft, des Friedens und der Humanität, mithin einen Völkerrechtler im Widerstand.[3] Eine Haltung, die der dem NS-Regime kritisch gegenüberstehende und politisch weitgehend unbelastete Hermann Mosler nie einnahm. Wenngleich er sich andernorts zu Stauffenberg bekannte, so blieb seine Haltung zu seinem früheren Kollegen doch stets distanziert. Dieser Beitrag möchte der komplexen Stellung Bertholds von Stauffenberg innerhalb der Erinnerungskultur des heutigen Max-Planck-Instituts für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (MPIL) auf den Grund gehen, indem er schlaglichtartig Leben und Wirken des Völkerrechtlers am Institut untersucht und der Frage nachgeht, welche Bedeutung er heute für das historische Selbstverständnis des MPIL hat.

Zwischen Vaterlandsverrat und Heldenkult. Anmerkungen zu Quellenlage und Literaturstand

Anders als sein weitaus populärerer Bruder Claus von Stauffenberg, der das gescheiterte Bomben-Attentat auf Adolf Hitler am 20. Juli 1944 ausgeführt hatte, ist Berthold von Stauffenberg nur wenigen innerhalb der historisch interessierten deutschen Völkerrechtswissenschaft ein Begriff.[4] Sich Berthold von Stauffenberg historisch zu nähern, ist kein leichtes Unterfangen. Hierbei stößt man schnell auf zwei grundlegende Probleme: einen eklatanten Mangel an Quellen und eine hierzu in keinem Verhältnis stehende Überproduktion von Literatur zum Thema „Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus“.[5] Weder Stauffenbergs Wirken am Institut, noch seine Rolle im Widerstand lässt sich jenseits seiner wissenschaftlichen Publikationen auf stabiler Faktenbasis nachvollziehen, da viele Absprachen im Geheimen und mündlich stattfanden und belastende Dokumente nach dem Scheitern des Attentats vernichtet wurden.[6]

Bei dem Blick in die Literatur lässt sich festhalten, dass Bewertung und Stellung des Widerstands in der deutschen Erinnerungskultur starken Konjunkturen unterlagen, die von vehementer Ablehnung bis zum Heldenkult reichten. Bis weit in die 1950er Jahre hielten sich nationalsozialistische Deutungsmuster, galten die Verschwörer des 20. Juli 1944 manchen als „Eidbrecher“ und „Vaterlandsverräter“, die ihren Kameraden an der Front feige in den Rücken gefallen seien.[7] Erst ab den 1960ern wandelte sich das Bild. In dem Maße, in dem sich die früheren Träger des „Dritten Reiches“ als Funktionselite der Bundesrepublik etablierten und sich in die neue demokratische Ordnung integrierten, wurden die überwiegend aus Adel, Großbürgertum und Militär stammenden Verschwörer des 20. Juli 1944 als Vertreter des „anderen Deutschland“ idealisiert. Während in der Bundesrepublik der bereits seit 1933 aktive kommunistische und sozialdemokratische Widerstand marginalisiert wurde, erhob man nun jene zu Vorkämpfern und Kronzeugen einer freiheitlich demokratischen Wertordnung, die sich erst kurz vor dem Ende des Krieges gegen Hitler gestellt hatten.[8] In der wissenschaftlichen Literatur und öffentlichen Wahrnehmung wurden die Verschwörer, wie Thomas Karlauf schreibt, fortan im Sinne der gesellschaftlichen Vorbildfunktion zu „weitgehend immune[n] Lichtgestalten“ stilisiert:

„Statt zu fragen, wie sie es schafften, sich von der Begeisterung der Mehrheitsgesellschaft abzusetzen und sich zu einer eigenen Haltung durchzuringen, setzte man auf die Fiktion mehr oder weniger ‚autarker‘ Persönlichkeiten, die prinzipiell die Gegenposition zu Hitler verkörperten und niemals vom rechten Weg abkamen.“[9]

Wie auch Ruth Hoffmann in ihrer unlängst erschienenen Studie zum deutschen Widerstand hervorhebt, wurden und werden Ambivalenzen in der Wahrnehmung der Widerstandskämpfer zumeist ignoriert.[10] Dies gilt auch für den Großteil der Publikationen zu Berthold von Stauffenberg, dessen Beteiligung am Widerstand rückblickend als freiheitlich-demokratischer Akt in quasi vorauseilender Verwirklichung des Grundgesetzes gesehen wird, wobei seine zeitgeisttypischen antidemokratischen, antisemitischen und auch nationalsozialistischen Überzeugungen in den Hintergrund gerückt werden.

„Im Grunde vollkommen überflüssig“. Berthold von Stauffenberg am KWI

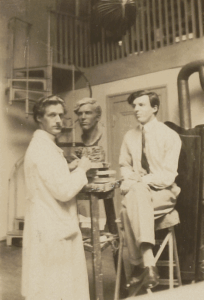

Berthold von Stauffenberg (rechts) mit Frau Schmitz, der Ehefrau des stellvertretenden Institutsdirektors Ernst Martin Schmitz, auf der Betriebsfeier des Instituts 1939[11]

Berthold von Stauffenberg kam 1929 kurz nach der Verteidigung seiner Tübinger Dissertation an das Institut, das ihm durch seine beiden Berliner Studiensemester bei Viktor Bruns bekannt war.[12] Stauffenbergs Eintritt in das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut (KWI) war jedoch nur als Übergang gedacht, da er weder eine wissenschaftliche noch eine juristische Karriere anstrebte.[13] Stattdessen hatte Stauffenberg sein Referendariat abgebrochen und sich 1928 erfolglos um die Aufnahme in den Auswärtigen Dienst beworben.[14] Nach der Absage aus dem AA blieb Stauffenberg zunächst bis 1931 am Institut, ehe ihn Bruns als redigierenden Sekretär in die von Åke Hammarskjöld geleitete Kanzlei des Ständigen Internationalen Gerichtshofs (StIGH) nach Den Haag vermittelte.[15] Wenngleich Stauffenberg hier hauptsächlich in der Verwaltung tätig war, wurde er häufig als Gutachter herangezogen. Schließlich erhielt er von Hammarskjöld den Auftrag zur Abfassung eines Kommentars zum Statut des StIGH, welcher 1934 über das KWI in französischer Sprache erschien und als Stauffenbergs wissenschaftliches Hauptwerk gilt.[16] Doch seine Tätigkeit in Den Haag vermochte den Juristen nicht zufrieden zu stellen. Sein Verhältnis zur internationalen Gerichtsbarkeit, die er für einen „Schwindel“ hielt, war durchaus nicht von zustimmender Überzeugung geprägt.[17] So schrieb er seinem „Meister“, dem Dichter Stefan George, dessen intellektuellem Kreis er seit frühester Jugend angehörte: „Die richter hier scheinen in einen zustand immer grösserer vertrottelung zu geraten und es wäre das beste man würden den ganzen haufen nach hause schicken“.[18] Nach dem Austritt Deutschlands aus dem Völkerbund im Jahre 1933 kündigte Stauffenberg seine Stelle, da er „es nicht für richtig halte weiter einen gehalt [sic] vom Völkerbund zu beziehen“.[19] Ein Schritt, den Hammarskjöld für „unnötig“ hielt und mit „grosse[r] Enttäuschung“ aufnahm.[20] Stauffenberg kehrte an das Institut zurück und versuchte es 1934 ein zweites Mal erfolglos beim Auswärtigen Amt. Obgleich er die Rechtswissenschaft eigentlich für sich ausgeschlossen hatte, bewarb er sich 1934, ebenfalls vergeblich, um einen Völkerrechtslehrstuhl in München.[21] So blieb Stauffenberg notgedrungen am KWI, an dem er seine Arbeit für „im grunde [sic] vollkommen überflüssig“ hielt.[22] Seinen Dienst am Institut versah er zwischen 11 und 18 Uhr nach ausgedehnten morgendlichen Reiteinheiten im Tattersall Beermann am Zoologischen Garten eher nach Vorschrift.[23] Stauffenbergs mangelnde Erwärmung für den juristischen Beruf und seine gescheiterten Bewerbungen an das AA und die Universität München 1934 hat die (juristische) Forschung als frühes Zeichen widerständiger Haltung beziehungsweise fehlender NS-Konformität gesehen.[24] Jedoch scheint der eigentliche Grund hierfür in einer ausgeprägten Gehemmtheit Stauffenbergs im persönlichen Auftreten gelegen zu haben.[25] Sein Verhältnis zur Rechtswissenschaft blieb für den musisch und literarisch breit Interessierten distanziert, wie sein langjähriger Kollege Alexander N. Makarov festhält: „Berthold von Stauffenberg hat mir einmal gesagt, er hätte kein einziges juristisches Buch zu Hause. (…) [D]ie Rechtswissenschaft war im Grunde genommen nur sein Beruf, nicht seine Berufung.“[26]

Viktor Bruns wollte Stauffenberg dennoch am Institut halten und förderte ihn nach Kräften. 1934 wurde Stauffenberg zum stellvertretenden Abteilungsleiter für Völkerrecht befördert, 1935 wurde er als Nachfolger des wegen seiner jüdischen Wurzeln aus dem Institut vertriebenen Erich Kaufmann zum wissenschaftlichen Mitglied und Mitherausgeber der ZaöRV ernannt.[27] In demselben Jahr wurde Stauffenberg zum Leiter der kriegsrechtlichen Abteilung im KWI befördert sowie Mitglied im wehrmachtsnahen Ausschuss für Kriegsrecht der Akademie für Deutsches Recht von Hans Frank. Auch war er mit Carl Bilfinger, Carl Schmitt und Ernst Schmitz Mitglied des Ausschusses für Völkerrecht der Akademie.[28] Schwerpunkt von Stauffenbergs wissenschaftlicher Arbeit im Institut war die Herausgabe der ersten Bände der Fontes Iuris Gentium zusammen mit Ernst Martin Schmitz und Abraham Feller. Der Großteil seiner Publikationen setzte sich mit dem Haager Gerichtshof auseinander.[29] Viktor Bruns sah in Stauffenberg einen derart verlässlichen Mitarbeiter, dass er ihn in seinem Testament, nach seinem Cousin Carl Bilfinger, als zweite Option für seine Nachfolge vorschlug.[30]

„Die Grundideen des Nationalsozialismus zum größten Teil durchaus bejaht“. Haltung zum „Dritten Reich“

„Der Gedanke des Führertums, der selbstverantwortlichen und sachverständigen Führung, verbunden mit dem einer gesunden Rangordnung und dem der Volksgemeinschaft, der Grundsatz ‚Gemeinnutz geht vor Eigennutz‘ und der Kampf gegen die Korruption, die Betonung des Bäuerlichen und der Kampf gegen den Geist der Großstädte, der Rassegedanke und der Wille zu einer neuen, deutsch bestimmten Rechtsordnung erschien uns gesund und zukunftsträchtig“[31]

– Verhörprotokoll Berthold von Stauffenberg 16. Oktober 1944

Berthold von Stauffenberg hatte, wie auch das KWI als solches, zunächst kein Problem mit dem Nationalsozialismus. Die Entlassung und Flucht von als Juden verfolgten Institutskollegen löste keinen Protest bei ihm aus, den Austritt Deutschlands aus dem Völkerbund nahm er mit Erleichterung auf. Zur “Röhm-Affäre” 1934, zur NS-Gleichschaltungspolitik, zur Aufhebung von Bürgerrechten oder zur Reichspogromnacht 1938 sind keine Äußerungen Stauffenbergs überliefert – weder zustimmende noch ablehnende. Kontrovers diskutiert werden zwei in der ZaöRV erschienene Aufsätze, die zu den wenigen wissenschaftlichen Stellungnahmen Stauffenbergs zur NS-Politik zählen: „Die Entziehung der Staatsangehörigkeit und das Völkerrecht – Eine Entgegnung“ (1934)[32] und „Die Vorgeschichte des Locarno-Vertrages und das russisch-französische Bündnis“[33] (1936). Beide Beiträge rechtfertigen juristisch zwei entscheidende Etappen der nationalsozialistischen (Völker-)Rechtsbruch-Politik.

Erklärt sich Stauffenbergs Rechtfertigungsschrift zum völkerrechtswidrigen Einmarsch deutscher Truppen in das demilitarisierte linksrheinische Gebiet 1936 mit klassischem deutschen Großmachtdenken, so lässt sich sein Aufsatz zur Staatsangehörigkeitsfrage als implizite Zustimmung zur nationalsozialistischen Judenverfolgung lesen.[34] Im Juli 1933 erließ die Reichsregierung das Gesetz über den Widerruf von Einbürgerungen und die Aberkennung der deutschen Staatsangehörigkeit. Das Gesetz sah vor, Einbürgerungen aus dem Zeitraum vom 9. November 1918 bis zum 30. Januar 1933 zu widerrufen, sofern diese als „unerwünscht“ anzusehen seien (§ 1). Die Unerwünschtheit bemaß sich laut der zugehörigen Durchführungsverordnung nach „völkisch-nationalen Grundsätzen“, explizit sollten neben Kriminellen auch „Ostjuden“ hierunter erfasst sein.[35]

Das Gesetz hatte den französischen Juristen Georges Scelle zu einer engagierten Stellungnahme veranlasst.[36] Stauffenbergs unmittelbare Entgegnung richtet sich dezidiert an ein internationales Publikum, gegenüber dem das deutsche Gesetz gerechtfertigt werden sollte. Anders als Scelle, der das Gesetz vor allem inhaltlich bewertet, argumentiert Stauffenberg positivistisch, insbesondere weist er den von Scelle erhobenen Vorwurf des Rechtsmissbrauchs zurück. Denn: „Die Entziehung der Staatsangehörigkeit um der Reinheit der Nation willen läßt sich ohne weiteres begreifen.“[37] Stauffenberg argumentiert im Folgenden vorwiegend rechtsvergleichend und kommt zu dem Schluss, dass der Entzug der Staatsangehörigkeit eine souveräne nationalstaatliche Entscheidung sei, die nicht im Widerspruch zur Staatenpraxis und zum Völkerrecht stehe.

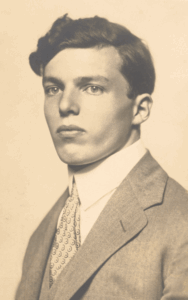

Berthold und Claus von Stauffenberg, um 1925[38]

Das mochte sachlich richtig argumentiert sein und für sich genommen wenig Rückschlüsse auf eine antisemitische Haltung des Verfassers geben – so wie auch Stauffenbergs Kommentar zum StIGH-Statut seine Ablehnung der internationalen Gerichtsbarkeit nicht zum Ausdruck brachte. Auch bedient sich Stauffenberg keinesfalls einer völkisch-rassistisch geprägten Sprache, die mit wenigen Ausnahmen auch nicht dem Habitus und Stil des Instituts entsprochen hätte.[39] Setzt man den Text jedoch mit anderen zeitgenössischen Dokumenten in Bezug, so fügt er sich in eine für weite Teile der damaligen deutschen Elite zeitgeisttypische antisemitische Grundhaltung ein, die auch von Bertholds Bruder Claus geteilt wurde.[40] Diese Einstellung bekundete Stauffenberg auch bei der Vernehmung nach seiner Verhaftung im Juli 1944:

„Auf innenpolitischem Gebiet hatten wir die Grundideen des Nationalsozialismus zum größten Teil durchaus bejaht.“[41]

Hierzu gehörte auch die Rassepolitik:

„Der Rassegedanke ist in diesem Krieg aufs schwerste verraten worden, indem gerade das rassisch beste deutsche Blut unwiederbringlich hingeopfert wird, während gleichzeitig Deutschland durch Millionen fremder Arbeiter bevölkert ist, die sicher nicht als rassisch hochwertig zu bezeichnen sind.“[42]

Beide Brüder hatten die Rassengrundsätze „an sich bejaht“, wenngleich schließlich für „überspitzt und übersteigert“ gehalten.[43]

Zur Führung berufen. Der Weg in den Widerstand

„Statt ‚berufener‘ Führer kamen im allgemeinen ‚kleine Leute‘ an die Spitze, die eine unkontrollierte Macht ausübten. Gegen den Gedanken der Volksgemeinschaft wurde verstoßen, indem gegen die oberen Schichten und die ‚Intellektuellen‘ gehetzt und überhaupt nach Möglichkeit das Ressentiment des Kleinbürgers geweckt wurde.“[44]

– Verhörprotokoll Berthold von Stauffenberg 16. Oktober 1944

Erste Zweifel Berthold von Stauffenbergs am nationalsozialistischen Deutschland sind vom Sommer 1942 überliefert.[45] Diese Zweifel bezogen sich auf die militärische Lage, da Stauffenberg kaum mehr daran glaubte, dass Deutschland den Krieg gewinnen könne.[46] Als Jurist war Stauffenberg ab Mitte der 1930er Jahre an der rechtlichen Vorbereitung eines zu erwartenden nächsten Krieges beteiligt gewesen, von dem er sich eine erneute deutsche Hegemonie in Europa erhoffte.[47] Bei seiner Tätigkeit im Ausschuss für Kriegsrecht erarbeitete er bis 1939 eine neue deutsche Prisenordnung, die Maßnahmen von Kriegsschiffen gegenüber neutralen und feindlichen Handels- und Passagierschiffen regulierte. Ferner war er an der Ausarbeitung einer neuen Luftkriegsordnung beteiligt.[48] Hierbei handelte und dachte er im Rahmen des geltenden Kriegsvölkerrechtes.

Seit Kriegsbeginn war das KWI innerhalb des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht (OKW) dem für völkerrechtliche Fragen der Kriegsführung zuständigen „Amt Ausland-Abwehr“ unterstellt.[49] Auch Stauffenberg war zum Kriegsdienst verpflichtet, den er im Oberkommando der Marine (OKM) leistete. Zu seinen Aufgaben gehörte die Ausarbeitung von Gutachten zu Völkerrechtsfragen für das OKM. Hierbei kam Stauffenberg, wie auch die anderen KWI-Mitarbeiter, mit den Rechtsbrüchen der deutschen Kriegsführung in Kontakt. War für Stauffenberg der Krieg lange ein legitimes Mittel zur Durchsetzung deutscher Interessen und zur Überwindung des Versailler „Diktatfriedens“ gewesen, schien ihm mit der fortschreitenden Eskalation an der Ostfront ein Ausmaß erreicht, das für ihn nicht mehr tragbar war.[50] Wann dieser Punkt genau erreicht war, lässt sich mangels Quellen nicht eruieren.[51]

Eine geheime Opposition gegen das NS-Regime in zivilen und militärischen Kreisen hatte schon seit 1933 bestanden. Auch Berthold von Stauffenberg war immer wieder mit Vertretern des Widerstands in Kontakt gekommen, so mit Helmuth James Graf von Moltke, einem der führenden Köpfe des „Kreisauer Kreises“, der ebenfalls als Völkerrechtsexperte an das OKW abgeordnet war. Dennoch schloss er sich keiner Gruppe an. Erste konkrete Attentatspläne diskutierten Berthold und Claus im Sommer 1943.[52] Unter dem Druck der sich rapide verschlechternden militärischen Lage arbeiteten zivile und militärische Oppositionsgruppen um den „Kreisauer Kreis“, den ehemaligen Leipziger Oberbürgermeister Carl Friedrich Goerdeler und den früheren Generalstabschef Ludwig Beck zusammen und entwarfen einen als „Operation Walküre“ bekannt gewordenen Umsturzplan. Stauffenbergs Bruder Claus geriet in das Zentrum des militärischen Widerstands. Sein wichtigster Berater und Vertrauter war hierbei Berthold von Stauffenberg.[53]

Aufgrund der verschiedenen politischen Zielsetzungen der einzelnen Gruppen – einig waren sie sich nur darin, Hitler beseitigen und den Krieg beenden zu wollen – verzichteten sie auf die detaillierte Planung einer Nachkriegsordnung. Die beiden Stauffenberg-Brüder hatten jedoch für sich einen „Eid“ abgelegt, in dem sie Grundzüge ihrer eigenen, von adeligem Standesdenken und Georgeschen Idealen geprägten Zukunftsvisionen skizzierten: „Wir wollen eine Neue Ordnung, die alle Deutschen zu Trägern des Staates macht und ihnen Recht und Gerechtigkeit verbürgt, verachten aber die Gleichheitslüge und beugen uns vor den naturgegebenen Rängen.“[54] Diese elitäre Haltung kommt auch bei der Vernehmung Stauffenbergs zum Ausdruck, wie der Bericht des Sicherheitsdienstes (SD) nicht undespektierlich festhält:

„Nach der Auffassung der Verschwörer ist die zur Führung berufene Schicht des Adels und des intelligenten Bürgertums durch den Nationalsozialismus abgelöst worden durch Emporkömmlinge, kenntnislose Schreier ohne Bildung und Kinderstube, die nun von der ihnen zur Verfügung stehenden Macht in absolut eigennütziger und selbstsüchtiger Weise Gebrauch machen“ [55]

Den Abend vor dem Attentat hatten beide Brüder in Bertholds Wohnung verbracht und waren alle Pläne noch einmal durchgegangen. Bereits am 17. Juli hatte Stauffenberg indirekt Hermann Mosler ins Vertrauen gezogen, der mit Stauffenberg und Moltke zusammengearbeitet und einem kritischen Institutsgesprächskreis angehört hatte, in dem man sich über die deutsche Kriegsführung ausgetauscht hatte.[56] Nach dem gescheiterten Attentat wurde Berthold von Stauffenberg zusammen mit seinem Bruder im Bendlerblock verhaftet. Während Claus dort standrechtlich exekutiert wurde, wurde Berthold in Gewahrsam genommen und 21 Tage lang von der Gestapo verhört. Ob er dabei, wie viele andere, gefoltert wurde, ist nicht überliefert. Am 10. August 1944 wurde er vor dem Volksgerichtshof wegen Hoch- und Landesverrats angeklagt und in einem Schauprozess durch den Volksgerichtshofpräsidenten Roland Freisler zum Tode durch den Strang verurteilt. Das Urteil wurde noch am selben Tag vollstreckt, die durch die Hinrichtung angefallenen „Gebühren“ wurden den Hinterbliebenen in Rechnung gestellt.[57] Die Familien Claus‘ und Bertholds von Stauffenberg wurden in „Sippenhaft“ genommen, was hieß, dass ihre Kinder in Heime verbracht und die Ehefrauen in KZs inhaftiert wurden. Sie überlebten das Ende des „Dritten Reiches“.

Ein frühes, aber vorsichtiges Bekenntnis. Berthold von Stauffenberg im kollektiven Gedächtnis des Instituts

Für die Institutsangehörigen bedeutete die Verhaftung und Hinrichtung Stauffenbergs einen Schock. Durch den Tod des Direktors Viktor Bruns im September 1943 in gewisser Weise „führungslos“ geworden, hatte sich am KWI, wie Rüdiger Hachtmann schreibt, eine Atmosphäre von „Denunziantentum und Misstrauen“ ausgebildet. Schon im Januar 1944 war der Institutsmitarbeiter Wilhelm Wengler von seinem Kollegen Herbert Kier wegen einer defätistischen Äußerung denunziert und von der Gestapo verhaftet worden.[58] Kurz vor dem Attentat waren Teile des Instituts aus Berlin in das Umland evakuiert worden. Nach der Verhaftung Stauffenbergs befürchtete man Razzien und Festnahmen im KWI, die jedoch ausblieben.[59] Die Bestürzung über das Schicksal des Kollegen wurde schnell eingeholt von den für das Institut nicht minder dramatischen Ereignissen des Kriegsendes, wie die Zerstörung der Institutsräume im Berliner Schloss, die Vernichtung großer Teile der Bibliothek und die Flucht von Mitarbeitern vor der Roten Armee.

Dennoch wurde Berthold von Stauffenberg keinesfalls vergessen. Bereits 1947 veröffentlichte Alexander N. Makarov in der „Friedenswarte“ einen Nachruf auf seinen früheren Kollegen, der in der Reihe „Vorkämpfer der Völkerverständigung und Völkerrechtsgelehrte als Opfer des Nationalsozialismus“ erschien.[60] Die Anfrage zur Abfassung des Erinnerungstextes zu Stauffenberg war eigentlich von Hans Wehberg direkt an Mosler gegangen, der diesen an Makarov delegiert hatte.[61] Auf Makarovs in der ersten Version sehr vorsichtigen Text entgegnete er, dass man „diese günstige Gelegenheit wahrnehmen sollte, die Ehrenrettung des Instituts in einer etwas prononcierteren Weise vorzunehmen, als Sie es bei der Schilderung […] der Beteiligung Bertholds am 20. Juli getan haben. Vielleicht können Sie die darauf bezogenen Sätze als Tatsachen bringen, nicht als Wissen vom Hörensagen. […] Dass Sie Strebels oder meinen Namen als Quellen nennen, scheint mir weder notwendig, noch richtig zu sein.“[62] Mosler, der redaktionell nicht unerheblich in Makarovs Text eingriff, nutzte Stauffenberg hier gezielt und geschickt zur Wiederherstellung des Institutsrufes.

Das erste öffentliche Bekenntnis seitens des Instituts als Ganzes findet sich 1951 in der ersten Nachkriegsausgabe der ZaöRV. In sechs Nekrologen wird dort jener Kollegen gedacht, die während des Krieges und der Nachkriegszeit verstorben waren, unter ihnen Berthold von Stauffenberg. Diese frühe Positionierung zu Stauffenberg ist angesichts der öffentlichen Haltung zum deutschen Widerstand und auch der geringschätzenden Meinung des politisch belasteten Institutsdirektors Carl Bilfinger über seinen ehemaligen Mitarbeiter nicht selbstverständlich.[63] Verfasst wurde der Nachruf vom ZaöRV-Schriftleiter Helmut Strebel, den ein enges persönliches Verhältnis mit Stauffenberg verbunden hatte. Strebels Würdigung ist politisch zurückhaltend, er nimmt Stauffenbergs Widerstandsakt nicht für das Institut im Allgemeinen in Anspruch und betont, dass „seine Beteiligung an den Umsturzplänen erst unmittelbar vor dem Attentat einzelnen andeutend bekannt wurde.“ Hierin unterscheidet er sich von Alexander N. Makarov, der eine größere Implikation des KWI in die Widerstandsplanung andeutet.[64] Gemeinsam ist beiden Nachrufen, dass sie vor allem Stauffenbergs Bedeutung als Wissenschaftler würdigen, wobei sie seinen StIGH-Kommentar hervorheben. Sie erwähnen auch den Locarno-Aufsatz, nicht aber denjenigen zur Staatsangehörigkeit.[65] Beide Nachrufe äußern sich nicht zur Motivation Claus von Stauffenbergs für das Attentat.

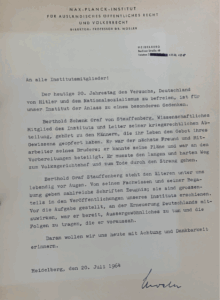

Ähnlich hielt es Hermann Mosler, der 1954 das Direktorium von Carl Bilfinger übernahm. Auch er bekannte sich früh zu Berthold von Stauffenberg, ging jedoch jeder näheren Qualifizierung der Motivationen des Widerstandskämpfers aus dem Weg. Gegenüber Karl Josef Partsch äußerte er 1966, dass er sowohl zum zehnten Jahrestag des Attentats 1954 vor Studenten in Frankfurt als auch zum 20. Jahrestag 1964 eine Rede gehalten habe, das zweite Mail jedoch als Direktor für die Belegschaft des Instituts, was ihm bedeutend schwerer gefallen sei.[66] Hier zeigt sich ein Grundmuster im Umgang Moslers mit der NS-Geschichte. Scheute er sich nicht, in der außerinstitutionellen (Fach-) Öffentlichkeit deutlich Stellung gegen den Nationalsozialismus zu beziehen[67], vermied er innerhalb des Instituts jede historische Auseinandersetzung.[68] Wenn Mosler sich zur Geschichte des Instituts äußerte, dann geschah dies so knapp als möglich ausschließlich zu offiziellen Jubiläumsveranstaltungen. Die erste öffentliche Stellungnahme Moslers zu Stauffenberg und zur NS-Zeit am Institut erfolgte 1961 anlässlich des 50-jährigen Jubiläums der Kaiser-Wilhelm-/Max-Planck-Gesellschaft:

„Die nationalsozialistische Epoche schränkte die Wirkungsmöglichkeiten allmählich und in zunehmendem Maße ein, ohne aber die wissenschaftliche Objektivität der Arbeiten zu zerstören. Alle Mitarbeiter, die das Regime ablehnten, verdankten dem Geschick von Bruns und der unbeirrbaren Sachlichkeit von Schmitz, im Institut eine Zuflucht und die Freiheit der wissenschaftlichen Entwicklung gefunden zu haben. Nach Bruns‘ Tod wuchs die Bedrängnis. In den ersten Kriegsjahren unterstützte das Institut durch Beratungen und Gutachten die Bemühungen des wissenschaftlichen Mitglieds Berthold Schenk Graf v. Stauffenberg, der im Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine völkerrechtliche Fragen bearbeitete, und von Graf Helmuth v. Moltke, der die entsprechende Tätigkeit im Oberkommando der Wehrmacht ausübte, um eine völkerrechtsgemäße Kriegsführung. Beide wurden Opfer der Terrormaßnahmen, die auf den 20. Juli 1944 folgten. Die mit Graf Stauffenberg getroffene Abrede, das Institut nach dem Umsturz der neuen Reichsregierung zur Verfügung zu stellen, blieb den Machthabern unbekannt.“[69]

Stauffenbergs Widerstand wird von Mosler gänzlich unpathetisch dargestellt, ohne dass Mosler sich diesen zu eigen macht. Auch Mosler spart die politisch-ideologischen Hintergründe für Stauffenbergs Attentat aus. Stattdessen findet an anderer Stelle in seiner Jubiläumsschrift eine Aneignung Stauffenbergs durch Mosler statt, indem Mosler explizit auf die Bedeutung seines StIGH-Kommentars von 1934 verweist und die Arbeit des Heidelberger MPIL in die Tradition der Internationalisierung des Rechts stellte.[70] Hierbei unterschlug er, dass Stauffenberg gegenüber dem Gericht sehr skeptisch war und die Abfassung des Kommentars als lästige Pflicht empfand.

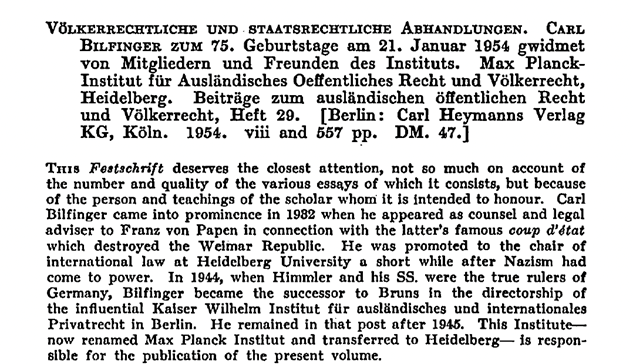

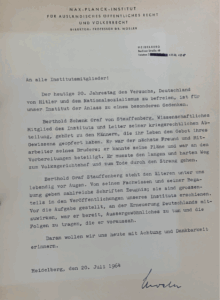

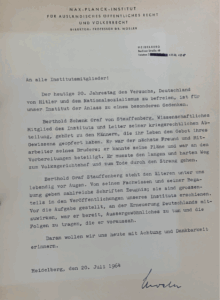

Schreiben Mosler zum 20. Jahrestag des Hitler-Attentats[71]

Moslers nüchtern-distanziertes Bekenntnis zu Stauffenbergs Widerstand, das er 14 Jahre später anlässlich des 50-jährigen Institutsjubiläums, anlässlich dessen eine Büste Stauffenbergs am Institut aufgestellt wurde, wortgleich wiederholen sollte, hatte verschiedene Gründe.[72] Der Direktor war sich bewusst, dass das „Dritte Reich“ von den Institutsangehörigen durchaus unterschiedlich erlebt worden und nicht jeder Mitarbeiter mit dem Attentat einverstanden gewesen war. Grundsätzliche und potentiell spaltende Debatten zur Rolle des Instituts und seiner Angehörigen im „Dritten Reich“ wollte Mosler in jedem Fall vermeiden. Wenngleich Mosler mit Stauffenbergs Tat durchaus übereinstimmte, mussten ihm viele politische, aber auch lebensanschauliche Einstellungen Stauffenbergs fremd geblieben sein. Mosler kannte Stauffenberg seit seinem eigenen Eintritt in das Institut 1937 und wusste um dessen Mitgliedschaft im Kreis um den Dichter Stefan George, in welchem eine elitäre, vielfach anti-demokratische und antiwestliche Geisteshaltung dominierte. Daran konnte und wollte Hermann Mosler nicht anknüpfen.

„Völkerrecht im Widerstand“? Fazit

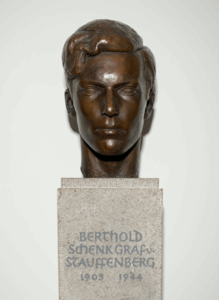

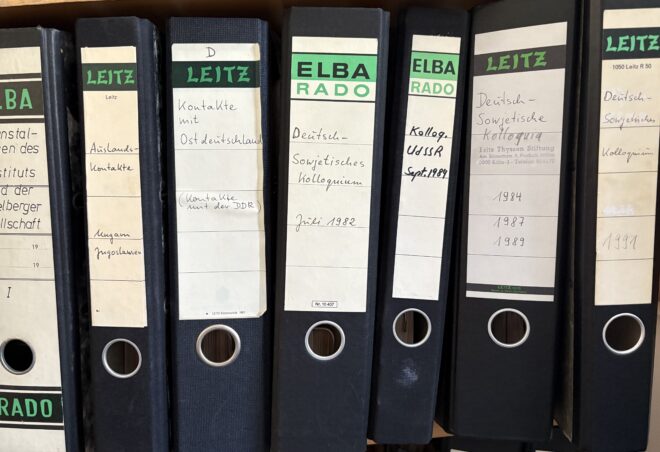

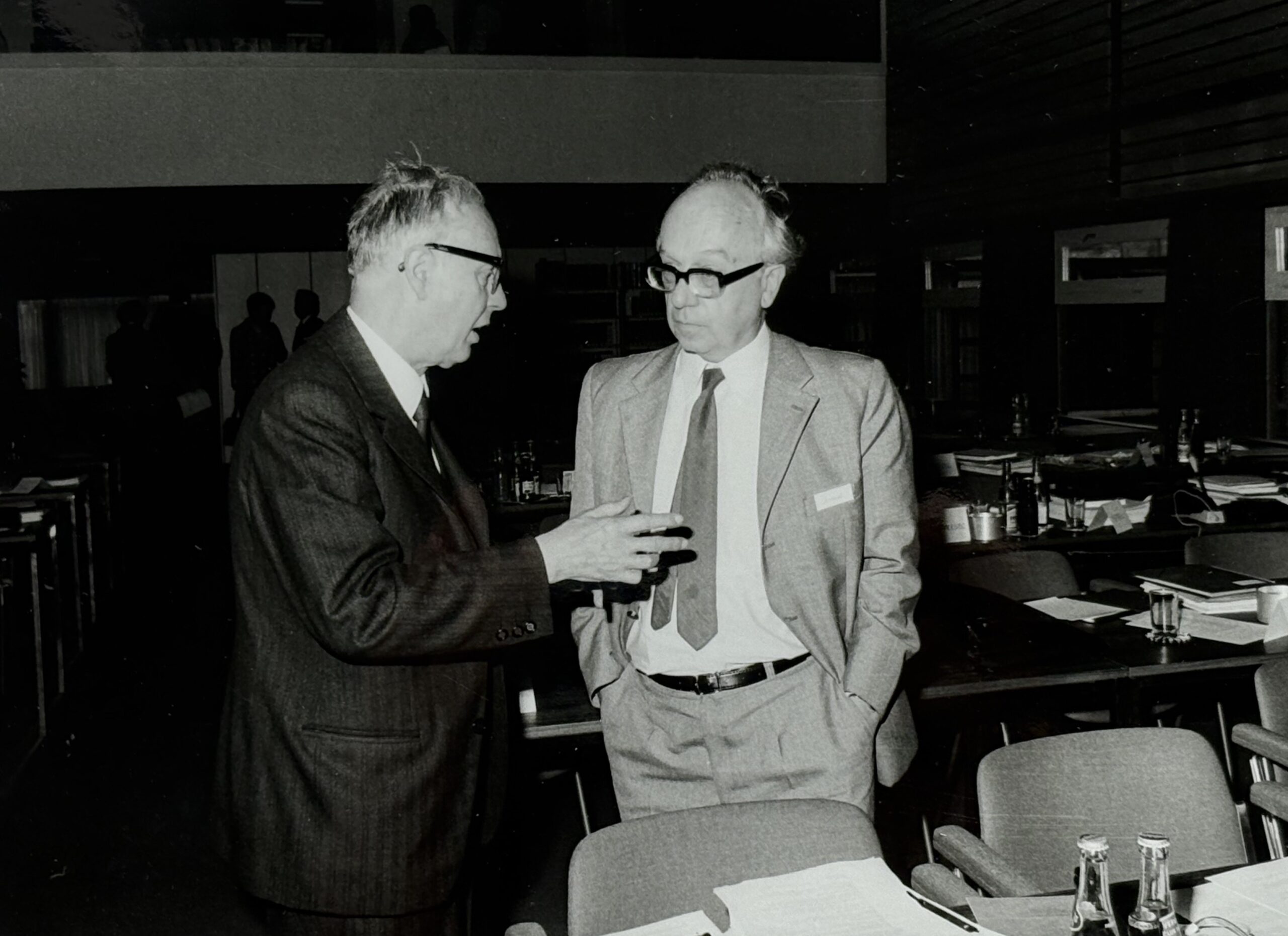

Am Institut blieb die Haltung zu Berthold von Stauffenberg komplex. Hermann Mosler befasste sich nach seiner Ansprache zum 50-jährigen Bestehen des Instituts 1975 nie mehr öffentlich mit der Geschichte des Instituts, auch sein Nachfolger Rudolf Bernhardt sparte in seiner Institutschronik von 2018 die Zeit vor 1949 und somit auch Stauffenberg als Institutsakteur aus. Andere Institutsangehörige wie Helmut Strebel setzten sich intensiv mit dem Leben und Werk Stauffenbergs auseinander und versuchten erfolglos auch das Direktorium hierfür zu erwärmen.[73] Eine Verbindung des Instituts mit Stauffenbergs Widerstand beziehungsweise eine Mobilisierung Stauffenbergs für die Rehabilitierung des eigenen Faches vermied insbesondere Hermann Mosler. Dies taten einzelne Exponenten der deutschen Völkerrechtswissenschaft erst eine Generation später, als sie Stauffenbergs Motivation zum Hitler-Attentat als „Völkerrecht im Widerstand“ zu deuten begannen.[74] Das zeigte sich auch innerhalb des Instituts, als Referent Theodor Schweisfurth 1987 im Zuge der Debatte um den Neubau beziehungsweise Umzug des Instituts nach Berlin den Vorschlag machte, das MPIL in „Berthold-von-Stauffenberg-Institut der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft“ umzubenennen.[75] Soweit kam es zwar nie, dennoch bekam die von Frank Mehnert geschaffene Stauffenberg-Büste unter dem Direktorium von Jochen Frowein und Rüdiger Wolfrum einen zentraleren Platz im 1996 neu gebauten Institut. Auch heute steht die Büste des jugendlichen Stauffenberg zentral am Eingang.

Die Stauffenberg-Büste von Frank Mehnert am Haupteingang des MPIL[76]

Doch fragt sich, was sie uns heute sagt und sagen soll – und wofür Stauffenberg heute steht. Im aktuellen Selbstverständnis der Forschenden am Institut stellt Berthold von Stauffenberg kaum mehr eine historische Referenzfigur dar, an der man die eigene Arbeit oder Haltung – in welcher Form auch immer – messen würde. Dafür liegen die Ereignisse des 20. Juli zu weit zurück und strahlen zu wenig aus. Auch gesamtgesellschaftlich ist die Deutung des Widerstands im Umbruch. Die starke Überzeichnung und symbolische Aufladung einzelner Akteure der Widerstandsbewegung, insbesondere des 20. Juli 1944, wirkt mittlerweile unglaubwürdig. In liberalen, aufgeklärten Kreisen sind Helden als Vorbildfiguren zur Überwindung der NS-Geschichte nicht mehr nötig, wir können uns mittlerweile den zeitgebundenen Ambivalenzen der Akteure jener Zeit stellen und halten diese aus. Und vielleicht ist es das, was uns im Institut Berthold von Stauffenberg heute vermittelt: die Erkenntnis historischer Zeitgebundenheit und lebensanschaulicher Komplexität. Doch ist beides gleichzeitig auch Aufgabe an uns. Stauffenberg ist uns Mahnung für die Verantwortung des Wissenschaftlers, er konfrontiert uns mit dem Erbe unserer belasteten Geschichte und lässt uns die Errungenschaft der freiheitlichen, liberalen Demokratie und des Rechtsstaats deutlich werden. Geschichte ist komplex und der Umgang mit ihr nicht einfach. Und wenn er einfach scheint, dann ist er falsch. Überlassen wir Stauffenberg also nicht jenen, die in diesen Zeiten allzu einfache Antworten bieten, sondern nehmen wir ihn als Einladung zur Auseinandersetzung mit uns selbst.

***

Der Verfasser dankt Sarah Gebel, Alexandra Kemmerer, Johannes Mikuteit, Moritz Vinken und Joachim Schwietzke für ihre hilfreichen Anmerkungen zum Text.

[1] Hermann Mosler, Staatsrechtslehre und Nationalsozialismus. Vorträge innerhalb der Studium-Generale-Reihe „Wissenschaft und Nationalsozialismus“ im Sommersemester 1966, unveröffentlichtes Typoskript, 3. Der Verfasser dankt Prof. Dr. Karl Mosler für die Überlassung des Textes.

[2] Mosler, Staatsrechtslehre (Fn. 1), 8; Rudolf Timmermans, Demokratie und Führerstaat: Studien über Begriffe und Formen des Volksstaates, Berlin: Fährmann-Verlag 1936.

[3] Alexander Meyer, Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (1905–1944). Völkerrecht im Widerstand, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2001, 261–262; Wolfgang Graf Vitzthum, Der stille Stauffenberg. Der Verschwörer, Georgeaner und Völkerrechtler Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2024, 152–153.

[4] Vitzthum, Der stille Stauffenberg (Fn. 3); Meyer (Fn. 3); ebenfalls zu nennen: Peter Hoffmann, Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg und seine Brüder, Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags Anstalt 1992. Allen Werken gemein ist die sehr affirmative Herangehensweise an den Biographierten. Zu Berthold von Stauffenberg ist überdies noch eine Reihe von Aufsätzen von Wolfgang Graf Vitzthum erschienen, die den Juristen im Kontext der georgeschen Geisteswelt diskutieren.

[5] Verwiesen sei hier beispielhaft auf die Bibliographie der Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung.

[6] Zu Stauffenbergs Wirken am Institut gibt es keine überlieferten zeitgenössischen Quellen. Stauffenbergs Personalakte im Archiv der MPG ist dünn und vollzieht v.a. seine innerinstitutionellen Karriereschritte nach. Durch die Zerstörung der Institutsräumlichkeiten im Berliner Schloss im Januar 1945 ist überdies ein Großteil der Institutsakten vernichtet worden, augenscheinlich haben auch Institutsmitarbeiter Unterlagen nach Stauffenbergs Verhaftung vernichtet.

[7] Ruth Hoffmann, Das deutsche Alibi. Mythos „Stauffenberg-Attentat“ – wie der 20. Juli 1944 verklärt und politisch instrumentalisiert wird, München: Goldmann 2024, 42.

[8] Hoffmann, Das deutsche Alibi (Fn. 7), 10.

[9] Thomas Karlauf, Stauffenberg. Porträt eines Attentäters, München: Pantheon 2019, 27.

[10] Hoffmann, Das deutsche Alibi (Fn. 7), 390.

[11] Foto: AMPG.

[12] Meyer (Fn. 3), 31.

[13] Meyer (Fn. 3), 47.

[14] Hoffmann, Stauffenberg (Fn. 4), 72.

[15] Vitzthum, Der stille Stauffenberg (Fn. 3), 51.

[16] Meyer (Fn. 3), 55.

[17] So schrieb Stauffenberg am 17.10.1932 an George: „Inzwischen bin ich wieder an die arbeit gegangen. nicht mit besonderer freude. Sie scheint nicht sonderlich sinnvoll – man lernt den schwindel rasch kennen. und dann bietet er einem nichts neues mehr“, zitiert nach: Vitzthum, Der stille Stauffenberg (Fn. 3), 51. Die Zitate Stauffenbergs sind allesamt in der für Stefan Georges minimalistischer Ästhetik folgenden Kleinschreibung gehalten.

[18] Brief von Berthold von Stauffenberg an Stefan George, datiert 27.10.1933, zitiert nach: Karlauf (Fn. 9), 124.

[19] Brief von Bertholf von Stauffenberg an Stefan George, datiert 27.10.1933, zitiert nach: Vitzthum, Der stille Stauffenberg (Fn. 3), 55.

[20] Hans Wehberg, Unveröffentlichte Lebensbeschreibung Berthold von Stauffenberg, Anlage eines Schreibens von Hans Wehbehrg an Hermann Mosler, datiert 15. August 1947, AMPG, III Rep 191 Nr. 20, Bd. 2.

[21] Meyer (Fn. 3), 59.

[22] Brief von Berthold von Stauffenberg an seine Frau Maria, zitiert nach: Hoffmann, Stauffenberg (Fn. 4), 151.

[23] Hoffmann, Stauffenberg (Fn. 4), 151.

[24] Meyer (Fn. 3), 58–59; Hoffmann, Stauffenberg (Fn. 4), 151. Zeitgenössische Quellen, die diese Sicht stützen würden, wurden bislang nicht aufgefunden.

[25] Zeitzeugen zufolge galt Stauffenberg als der „Schweiger“, da er im kollegialen Umgang als still und verschlossen galt und sich auch bei wissenschaftlichen Debatten im Institut kaum zu Wort meldete, vgl.: Joachim von Elbe, Unter Preußenadler und Sternenbanner. Ein Leben für Deutschland und Amerika, München: C. Bertelsmann 1983, 123; Helmut Strebel, Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (1905–1944), ZaöRV 13 (1950), 14–16; ferner: Hoffmann, Stauffenberg (Fn. 4), 492; Vitzthum, Der stille Stauffenberg (Fn. 3), 65. Ein namentlich nicht genannter früherer Mitarbeiter in der Gerichtsschreiberei des StIGH beschrieb Stauffenberg als „reserved and shy“. Ferner: „(H)e kept very much to himself (…) and made no friends amongst the staff of the court“, zitiert nach: Wehberg, Lebensbeschreibung (Fn. 20).

[26] Alexander N. Makarov, Vorkämpfer der Völkerverständigung und Völkerrechtsgelehrte als Opfer des Nationalsozialismus. Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (1905–1944), Die Friedenswarte. Blätter für internationale Verständigung und zwischenstaatliche Organisation 6 (1947), 360–365, 364.

[27] Wolfgang Graf Vitzthum, Stauffenberg, Berthold Alfred Maria Schenk Graf von, in: Achim Aurnhammer et al. (Hrsg.), Stefan George und sein Kreis: Ein Handbuch, München: De Gruyter 2016, 1666–1671, 1667.

[28] Andreas Toppe, Militär und Kriegsvölkerrecht. Rechtsnorm, Fachdiskurs und Kriegspraxis in Deutschland 1899–1940, München: De Gruyter 2008, 207–208.

[29] Vgl. die Bibliographie bei Makarov (Fn. 26), 365; ferner: Vitzthum, Der stille Stauffenberg (Fn. 3), 69.

[30] Testament Viktor Bruns, AMPG, PA Viktor Bruns, II. Abt., Rep. 0001A, Pag. 40.

[31] Bericht des Sicherheitsdienstes vom 16.10.1944, in: Hans-Adolf Jacobsen (Hrsg.), „Spiegelbild einer Verschwörung“. Die Opposition gegen Hitler und der Staatsstreich vom 20. Juli 1944 in der SD-Berichterstattung. Geheime Dokumente aus dem ehemaligen Reichssicherheitshauptamt, Bd. 1, Stuttgart: Seewald 1984, 447. Hervorhebung im Original.

[32] Berthold von Stauffenberg, Die Entziehung der Staatsangehörigkeit und das Völkerrecht – Eine Entgegnung, ZaöRV 4 (1934), 261–276.

[33] Berthold von Stauffenberg, Die Vorgeschichte des Locarno-Vertrages und das russisch-französische Bündnis, ZaöRV 6 (1936), 215–234.

[34] Karlauff (Fn. 9), 66. Die Stauffenberg-Forschung kommt jedoch durchweg zu dem Ergebnis, dass Stauffenbergs Aufsatz von 1934 keinerlei Rückschlüsse auf seine persönliche Einstellung zulasse. Allgemein wird der Aufsatz als reine Auftragsarbeit aus der Institutsleitung bzw. vom Auswärtigen Amt gedeutet, die Stauffenberg mehr oder weniger gegen seinen Willen durchgeführt habe, so: Meyer (Fn. 3), 62–63; Hoffmann, Stauffenberg (Fn. 4), 152; Wolfgang Graf Vitzthum, Berthold von Stauffenberg und das Widerstandsrecht, in: Frank-Lothar Kroll, Rüder von Voss (Hrsg.), Für Freiheit, Recht, Zivilcourage. Der 20. Juli 1944, Berlin: Bebra Verlag 2020, 145–174, 157–158.

[35] § 2 des Gesetzes sah den Entzug der Staatsangehörigkeit auch für im Ausland befindliche deutsche Staatsangehörige vor, sofern diese „durch ein Verhalten, das gegen die Pflicht zur Treue gegen Reich und Volk verstößt, die deutschen Belange geschädigt haben“, worunter v.a. „feindselige Propaganda“ gefasst wurde. Unmittelbar betroffen hiervon waren u.a. Schriftsteller und Kritiker wie Lion Feuchtwanger, Alfred Kerr, Heinrich Mann oder Kurt Tucholsky, was dem literaturaffinen Stauffenberg kaum entgangen sein kann.

[36] Georges Scelle, À propos de la loi allemande du 14 juillet 1933 sur la déchéance de la nationalité, Revue critique de droit international XXIX (1934), 63–76.

[37] Stauffenberg, Entziehung (Fn. 32), 265.

[38] Foto: Ullstein Bild.

[39] Ingo Hueck, Die deutsche Völkerrechtswissenschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Das Berliner Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, das Hamburger Institut für Auswärtige Politik und das Kieler Institut für Internationales Recht, in: Doris Kaufmann (Hrsg.), Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Bestandaufnahme und Perspektiven der Forschung, Göttingen: Wallstein 2000, Bd. 2, 490–528, 503; Rüdiger Hachtmann, Das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht 1924 bis 1945, MPIL100.de.

[40] Karlauff (Fn. 9), 66.

[41] Bericht des Sicherheitsdienstes (Fn. 31), 447. Hervorhebung im Original.

[42] Bericht des Sicherheitsdienstes (Fn. 31), 450.

[43] Bericht des Sicherheitsdienstes (Fn. 31), 450.

[44] Bericht des Sicherheitsdienstes (Fn. 31), 453.

[45] Brief von Berthold von Stauffenberg an Frank Mehnert, datiert 21. August 1942, zitiert nach: Karlauff (Fn. 9), 194–195.

[46] Auszug Vernehmung Berthold von Stauffenberg, 21.07.1944, Bericht des Sicherheitsdienstes (Fn. 31), 19.

[47] Hachtmann (Fn. 39).

[48] Toppe (Fn. 28), 207.

[49] Toppe (Fn. 28), 193. Vom Institut abgestellt wurden Hermann Mosler, Günter Jaenicke, Wilhelm Wengler und Ernst Martin Schmitz mit den Arbeitsschwerpunkten Land- und Seekrieg sowie Kriegsgefangenenrecht.

[50] Felix Lange, Praxisorientierung und Gemeinschaftskonzeption. Hermann Mosler als Wegbereiter der westdeutschen Völkerrechtswissenschaft nach 1945, Heidelberg: Springer 2017, 110.

[51] Vitzthum, Der stille Stauffenberg (Fn. 3), 110. Die von Institutsangehörigen überlieferten Gutachten waren im Einklang mit dem geltenden Kriegsvölkerrecht gehalten, womit sie nicht als Rechtfertigungen des Weltanschauungskrieges gelten können. Einen offenen Widerstand gegen das „Dritte Reich“ bedeuten sie indes nicht.

[52] Stauffenberg zu Kranzfelder, Herbst 1943, zitiert nach: Bericht des Sicherheitsdienstes (Fn. 31), 115.

[53] Meyer (Fn. 3), 90.

[54] Zitiert nach: Karlauff (Fn. 9), 298.

[55] Bericht des Sicherheitsdienstes (Fn. 31), 453. Zum vielfach ignorierten Quellenwert der Protokolle: Karlauff (Fn. 9), 25–26.

[56] Lange, Praxisorientierung (Fn. 50), 110. Dies beruht auf einer nicht durch Zeugnisse Dritter verifizierbaren Selbstauskunft Moslers.

[57] Vitzthum, Der stille Stauffenberg (Fn. 3), 150.

[58] Felix Lange, Kolonialrecht und Gestapo-Haft. Wilhelm Wengler 1933–1945, ZaöRV 76 (2016), 633–659, 649.

[59] Mit Ausnahme der Tagebuchaufzeichnungen der Bibliothekarin Annelore Schulz sind keine zeitgenössischen Quellen zur Institutssicht auf diese Ereignisse überliefert. Auch die Notizen von Annelore Schulz sind, vermutlich aus Angst vor Überwachung, zurückhaltend. „Die Attentatsgeschichte bewegt die Gemüter sehr. Wir fürchten alle, daß unser Graf Berthold Schenk v. Stauffenberg mit Familie nicht mehr lebt, für das Institut kann die Angelegenheit die schlimmsten Folgen haben.“, Eintrag 24. Juli 1944. Dass es nicht zu Razzien gekommen war, lag vermutlich daran, dass der Partei-Vertrauensmann Herbert Kier diese verhindert hatte: Lange, Kolonialrecht (Fn. 58), 638.

[60] Makarov (Fn. 26), 360–365.

[61] Brief von Hans Wehberg an Hermann Mosler, datiert 15. August 1947, AMPG, III Rep 191 Nr. 20, Bd. 2.

[62] Brief von Hermann Mosler an Alexander N. Makarov, datiert 13. Oktober 1947, AMGP, III Rep 191 Nr. 20, Bd. 2.

[63] Gegenüber Strebel hatte sich Bilfinger im Sommer 1945 sehr abfällig über Stauffenberg geäußert, was Strebel als „erstaunliche Geschmacklosigkeit“ empfand wie auch als Mangel an „Fähigkeit zu einem gewissen Schamgefühl“: Brief von Helmut Strebel an Hermann Mosler, datiert 4. Januar 1946, zitiert nach: Florian Hofmann, Helmut Strebel (1911-1992). Georgeaner und Völkerrechtler, Baden-Baden: Nomos 2010, 121.

[64] Makarovs Beitrag liest sich gleichermaßen als ein Nachruf auf Stauffenberg wie auch auf das „Bruns‘sche Institut“ selbst. So betont er, dass es ab Sommer 1943 zu regelmäßigen, offenen und regimekritischen Aussprachen Moltkes und Stauffenbergs mit den Institutsmitarbeitern gekommen sei. Makarov führt ferner die Episode um Moslers indirekte Einweihung in die Attentatspläne an, womit er eine Unterstützung des Widerstands durch das KWI suggeriert: Makarov (Fn. 26).

[65] Makarov erwähnt ihn aber in der von Helmut Strebel zusammengestellten und angefügten Bibliographie.

[66] Brief von Hermann Mosler an Karl Josef Partsch, ohne Datum, jedoch vor dem 4.2.1966, Mappe „Stefan George Stiftung“, Hausbestand MPIL. Der Vortrag von 1954 scheint nicht überliefert zu sein. Zur Ansprache von 1964: siehe Anhang.

[67] Mosler, Staatsrechtslehre (Fn. 1).

[68] Philipp Glahé, History as a Problem? On the Historical Self-Perception of the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, ZaöRV 83 (2023), 565–578.

[69] Hermann Mosler, Geschichte des Max-Planck-Instituts für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, in: Jahrbuch der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e. V., Bd. II (1961), 687–703, 696.

[70] Mosler, Geschichte (Fn. 69), 701.

[71] Scan aus: AMPG, III Rep 191, Nr. 101.

[72] Hermann Mosler, Aufgaben und Arbeitsweise des Instituts, in: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft (Hrsg.), Berichte und Mitteilungen 2 (1975), 7–21.

[73] Briefwechsel zwischen Helmut Strebel und Rudolf Bernhardt, Mappe „Betr. Nachforschungen Dr. Strebel im Bundesarchiv/Akten betr. Prisenrecht usw.“, MPIL.

[74] Meyer (Fn. 3).

[75] Theodor Schweisfurth, Vermerk betr. Neubau des Institutes, 4. Oktober 1987, 1–19, 19, Ordner „Institutschronik III, MPIL.

[76] Foto: Maurice Weiss/ MPIL.

In the summer semester of 1966, Heidelberg University held a Studium Generale lecture series on “Academia and National Socialism”. Two of the five lectures were delivered by Hermann Mosler. These lectures, held just before the onset of the student movement, are among the few public deliberations on the “Third Reich” by the international law scholar. By Mosler’s standards, they are remarkably direct and almost personal in tone. Born in 1912, he clearly aims to present the young students with a comprehensive picture of the National Socialist political philosophy and its origins, as well as the working and living conditions under the dictatorship: “I belong to a generation that, in 1933, was not capable to act, but was capable of judgement.”[1] Mosler goes on to say that as a student, a doctoral candidate, and a young scholar, he “formed an opinion on every stage. I see some things differently today, some more clearly, some less clearly than I thought I knew.”

Mosler provides a detailed account of the situation in Germany and within constitutional law scholarship in the late Weimar Republic, describes his field’s reaction to the National Socialist seizure of power, and details the expansion of the “total state” and the erosion of the rule of law. He does not shy away from taking a clear stance on key ideological figures of National Socialist legal scholarship, such as Carl Schmitt, Reinhard Höhn, or his own faculty colleague Ernst Forsthoff, and discusses their roles in legitimising the Nazi regime.

However, Mosler also points out that not every jurist blindly submitted to the Nazi state, and that there were courageous scholars who openly voiced dissent. He cites his former doctoral colleague in Bonn, Rudolf Timmermans, as an example. Timmermans had published a dissertation in 1936 that strongly criticised the Führer state and was consequently confiscated by the Gestapo. The author therefore had to flee abroad and did not survive the war.[2] However, one name is missing in Mosler’s lectures, even though one might expect to hear it, especially given the lecture’s date on 20 July 1966 – Berthold von Stauffenberg. Unlike the much less widely known Timmermans and despite his involvement in the resistance of 20 July 1944, Stauffenberg did not serve as a point of reference for Mosler in rehabilitating the discipline of international law. Some recent scholarship, however, presents Berthold von Stauffenberg as a paragon within the field during the “Third Reich” – as an advocate for the rule of law, the international community, peace, and humanity. In other words, an international lawyer in resistance.[3] This was a position that the politically mostly unencumbered Mosler never took. Even though Mosler did reference Stauffenberg positively elsewhere, he always maintained a certain distance. This essay seeks to explore the complex role of Berthold von Stauffenberg within the culture of remembrance at today’s Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (MPIL) by examining aspects of his life and work at the Institute and questioning his relevance to the Institute’s historical self-image.

Treason or Heroism? Notes on the Availability of Sources and the Existing Literature

Unlike his far more popular brother Claus von Stauffenberg, who carried out the failed bomb attack on Adolf Hitler on 20 July 1944, Berthold von Stauffenberg is only known to few historically interested German scholars of international law.[4] Approaching Berthold von Stauffenberg historically is no easy endeavour. In doing so, one quickly encounters two fundamental problems: a glaring lack of sources and a disproportionate overproduction of literature on the subject of “resistance against National Socialism”.[5] Neither Stauffenberg’s work at the Institute nor his role in the resistance can be reconstructed on a stable factual basis beyond his academic publications, as many agreements were made secretly and verbally and incriminating documents were destroyed after the failure of the assassination attempt.[6]

A look at the literature shows that the assessment and evaluation of the resistance within German remembrance culture was subject to strong fluctuations, ranging from vehement rejection to hero worship. National Socialist patterns of interpretation persisted well into the 1950s, and the conspirators of 20 July 1944 were regarded by some as “oath-breakers” and “traitors” who had cowardly and treacherously backstabbed their comrades at the front.[7] It was not until the 1960s that the narrative changed. While former supporters of the “Third Reich” established themselves as the functional elite of the new Federal Republic of Germany and integrated themselves into the new democratic order, the conspirators of 20 July 1944, who came predominantly from the aristocracy, the upper middle class, and the military, were idealised as representatives of “the other Germany”. While the communist and social democratic resistance, which had been active since as early as 1933, was marginalised in the Federal Republic, those who had only opposed Hitler shortly before the end of the war were now elevated to the status of pioneers and crown witnesses of a liberal democratic value system.[8] In academic literature and public perception, the conspirators were henceforth stylised as “paragons mostly immune from criticism” in the name of serving as social role models, according to Thomas Karlauf:

“Instead of asking how they managed to distance themselves from the euphoria of societal mainstream and come to their own opinions, one favoured the fiction of more or less ‘autarkic’ figures, who symbolized the fundamental opposite of Hitler and never strained from righteousness.”[9]

As Ruth Hoffmann also emphasises in her recently published study on the German resistance, ambivalences were and are mostly ignored in the perception of the resistance fighters.[10] This also applies to the majority of publications on Berthold von Stauffenberg, whose participation in the resistance is seen in retrospect as a liberal-democratic act in quasi-pre-emptive realisation of today’s democratic German constitution, whereby his anti-democratic, anti-Semitic, and even National-Socialist convictions, typical of the zeitgeist, are pushed into the background.

“Really Entirely Superfluous”. Berthold von Stauffenberg at the KWI

Berthold von Stauffenberg (right) with Mrs. Schmitz, the wife of the Institute’s deputy director Ernst Martin Schmitz, at the Institute’s staff party in 1939[11]

Berthold von Stauffenberg came to the Institute, which he knew from his two semesters studying in Berlin under Viktor Bruns, in 1929, shortly after defending his dissertation in Tübingen.[12] However, Stauffenberg’s employment at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (KWI) was only intended to be transitionary, as he was not aiming for a career in academia or law.[13] Instead, Stauffenberg had dropped out of his legal clerkship and unsuccessfully applied to join the Foreign Service in 1928.[14] After being turned down by the Foreign Office, Stauffenberg initially remained at the Institute until 1931, when Bruns assisted him in becoming an editorial secretary in the office of the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) under Åke Hammarskjöld.[15] Stauffenberg’s work there was mainly administrative, but he was frequently called upon for expert opinions. Eventually, Hammarskjöld commissioned him to write a commentary on the Statute of the PCIJ, which was published in French by the KWI in 1934 and is regarded as Stauffenberg’s main academic work.[16] However, his employment in The Hague did not satisfy the jurist. His relationship with international jurisdiction, which he regarded as a “charade”, was not at all characterised by approval.[17] He wrote to his “master”, the poet Stefan George, whose intellectual circle he had belonged to since his earliest youth: “the judges here seem to fall into a state of ever greater idiocy, and it would be best if the whole lot of them were sent home”.[18] After Germany withdrew from the League of Nations in 1933, Stauffenberg resigned from his position because he “did not think it right to continue drawing a salary from the League of Nations”[19] – a step that Hammarskjöld considered “uncalled for” and received with “great disappointment”.[20] Stauffenberg returned to the Institute and again applied to the Foreign Office in 1934, without success. Despite having ruled out a career in legal scholarship previously, he then applied, also in vain, for a chair in international law at the University of Munich in 1934.[21] It was for lack of a better option that Stauffenberg remained at the KWI, where he considered his work to be “really entirely superfluous”.[22] He performed his duties at the Institute between 11 a.m. and 6 p.m., after extensive morning horse riding sessions at the Beermann stable near the Berlin Zoological Garden.[23] Staufenberg’s lack of enthusiasm for a legal career as well as his failed application to the Foreign Service and Munich University have been interpreted by scholarship as early signs for his rebellious attitude and nonconformity with National Socialism.[24] However, the real reason seems to have laid in Stauffenberg’s pronounced social inhibitions.[25] While he was widely interested in the fine arts and literature, his relationship to law remained distant as Stauffenberg’s long-time colleague Alexander N. Makarov notes: “Berthold von Stauffenberg once told me that he did not own a single legal textbook. […] Law was really only his profession, not his vocation.”[26]

Viktor Bruns nevertheless wanted to keep Stauffenberg at the Institute and supported him to the best of his ability. In 1934, Stauffenberg was promoted to deputy head of the Department of International Law, and in 1935 he was appointed an academic member and co-editor of the Institute’s journal Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (ZaöRV, English title: Heidelberg Journal of International Law, HJIL). In this position he succeeded Erich Kaufmann, who had been expelled from the Institute due to his Jewish roots.[27] In the same year, Stauffenberg was promoted to Head of the Department for the Law of War at the KWI and became a member of Hans Frank’s Committee for the Law of War at the Academy for German Law (Akademie für Deutsches Recht), which was closely linked to the German military (Wehrmacht). He was also a member of the Academy’s Committee for International Law, along with Carl Bilfinger, Carl Schmitt, and Ernst Schmitz.[28] The focus of Stauffenberg’s academic work at the Institute was the publication of the first volumes of the Fontes Iuris Gentium, together with Ernst Martin Schmitz and Abraham Feller. The majority of his publications dealt with the Hague Court.[29] Viktor Bruns trusted Stauffenberg to such an extent that, in his will, he pointed to him as a second option for his own successor, next to his cousin Carl Bilfinger.[30]

“For the Most Part Generally Affirmed”. Attitude towards the “Third Reich”

“The idea of Führertum, of self-reliant and expert leadership, combined with that of a healthy hierarchy and that of the Volksgemeinschaft, the principle of ‘common good before self-interest’ and the fight against corruption, the emphasis on the rustic and the fight against the metropolitan spirit, race ideology and the will for a new, German-determined legal order seemed healthy and promising to us.”[31]

– Berthold von Stauffenberg interrogation protocol of 16 October 1944

Berthold von Stauffenberg, like the KWI as a whole, was not opposed to National Socialism, initially. The dismissal and flight of Institute colleagues who were persecuted as Jews did not evoke any protest from him, and he was relieved when Germany left the League of Nations. There are no surviving statements by Stauffenberg – neither positive nor critical – on the Röhm murders of 1934, the policy of Gleichschaltung, the abolition of civil rights, or the November Pogroms of 1938. Two essays published in HJIL, which are among the few academic deliberations by Stauffenberg on National Socialist policy, are the subject of controversy: Die Entziehung der Staatsangehörigkeit und das Völkerrecht – Eine Entgegnung (“The Withdrawal of Citizenship and International Law – A Rebuttal”, 1934)[32] and Die Vorgeschichte des Locarno-Vertrages und das russisch-französische Bündnis (“The Origins of the Locarno Treaty and the Russian-French Alliance”, 1936)[33]. These contributions seek to justify, from a jurisprudential point of view, two decisive steps of the National Socialist policy of breaking (international) law.

While Stauffenberg’s justification of the invasion of German troops into the demilitarised area on the left bank of the Rhine in 1936, which violated international law, can be explained with traditional German imperialism, his article on the question of citizenship can be read as implicit approval of the National Socialist persecution of Jews.[34] In July 1933, the Reich government passed the “Act on the Revocation of Naturalisations and Withdrawal of German Nationality” (Gesetz über den Widerruf von Einbürgerungen und die Aberkennung der deutschen Staatsangehörigkeit). The law provided for naturalisations from the period between 9 November 1918 and 30 January 1933 to be revoked if they were considered “undesirable” (§ 1). According to the associated implementation ordinance, undesirability was to be measured according to “völkisch-national principles”, explicitly including Ostjuden [“Eastern Jews”] alongside criminals.[35]

The law had prompted the French jurist Georges Scelle to issue an impassioned statement.[36] Stauffenberg’s direct rebuttal was aimed squarely at an international audience, to whom the German law was to be justified. Unlike Scelle, who primarily assessed the content of the law, Stauffenberg utilizes legal positivism, rejecting in particular Scelle’s accusation of an abusive use of law, because: “The revocation of citizenship for the sake of the purity of the nation can easily be grasped.”[37] In the following, Stauffenberg argues primarily from a comparative law perspective and comes to the conclusion that the withdrawal of citizenship is a sovereign decision of the nation-state that does not contradict state practice and international law.

Berthold and Claus von Stauffenberg, around 1925[38]

This may have been a coherent argument and, in itself, does not give much indication of an anti-Semitic attitude on the part of the author – just as Stauffenberg’s commentary on the PCIJ Statute did not express his rejection of international jurisdiction. Furthermore, Stauffenberg did not make use of völkisch-racist language, which, with a few exceptions, would not have been in keeping with the Institute’s habitus and style.[39] However, if one compares the text with other contemporary documents, it is in line with an anti-Semitic attitude typical of the zeitgeist within large sections of the German elite at the time and shared by Berthold’s brother Claus.[40] Stauffenberg also expressed this attitude during the interrogation after his arrest in July 1944:

“In the area of domestic politics, we had for the most part generally affirmed the basic ideas of National Socialism.”[41]

This also included Rassenpolitik (“race policy”):

“The racial idea has been betrayed in the most serious way in this war, in that the racially superior German blood is being irretrievably sacrificed, while at the same time Germany is populated by millions of foreign workers who certainly cannot be described as being of high racial quality.”[42]

Both brothers had “generally affirmed” the racial principles, although they ultimately considered them to be “exaggerated and hyperbolized”.[43]

Called to Leadership. The Path to Resistance

“Instead of ‘born’ leaders, it was generally ‘ordinary people’ who came up on top, who exercised uncontrolled power. The idea of the Volksgemeinschaft was violated by agitating against the upper classes and the ‘intellectuals’ and generally trying to arouse the resentment of the petty bourgeoisie as much as possible.”[44]

– Berthold von Stauffenberg interrogation protocol of 16 October 1944

Berthold von Stauffenberg’s first doubts about National Socialist Germany can be traced back to the summer of 1942.[45] These doubts related to the military situation, as Stauffenberg no longer believed that Germany could win the war.[46] From the mid-1930s, Stauffenberg, as a legal scholar, had been involved in the legal preparations for an anticipated next war, which he hoped would lead to a renewed German hegemony in Europe.[47] As part of his work on the Committee for the Law of War, he finished drafting a new German prize order, which regulated the actions of warships towards neutral and enemy merchant and passenger ships, in 1939. He was also involved in the drafting of new law of aerial warfare.[48] In this capacity, he acted and thought within the framework of the applicable international law of war.

From the beginning of the war, the KWI was subordinated to the Foreign Defence Office (Amt Ausland-Abwehr) within the High Command of the Wehrmacht (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, OKW), which was responsible for international law issues relating to the conduct of the war.[49] Stauffenberg was not exempt from military service, which he performed in the High Command of the Navy (Oberkommando der Marine, OKM). His duties included preparing expert opinions on international law issues for the OKM. In doing so, Stauffenberg, like other KWI employees, came into contact with the ways Germany violated legal rules in its warfare. While Stauffenberg had long considered the war to be a legitimate means of asserting German interests and overcoming the “dictated peace” of Versailles, the progressive escalation on the Eastern Front was finally no longer acceptable to him.[50] It is impossible to ascertain exactly when this point was reached due to a lack of sources.[51]

Secret opposition to the National Socialist regime in civilian and military circles had existed since 1933 and Berthold von Stauffenberg repeatedly came into contact with representatives of the resistance, such as Helmuth James Graf von Moltke, one of the leading figures of the “Kreisau Circle”, who, too, was seconded to the OKW as an expert in international law. Nevertheless, Stauffenberg did not join any group. Berthold and Claus discussed their first concrete assassination plans in the summer of 1943.[52] Under the pressure of the rapidly deteriorating military situation, civilian and military opposition groups around the “Kreisau Circle”, the former mayor of Leipzig Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, and the former Military Chief of Staff Ludwig Beck joined forces and drew up a plan to overthrow the regime, which became known as Operation Walküre (“Operation Valkyrie”). Stauffenberg’s brother Claus found himself at the centre of the military resistance. His most important advisor and confidant in this was Berthold von Stauffenberg.[53]

Due to the different political objectives of the individual groups – they were only united in wanting to eliminate Hitler and end the war – they refrained from making any detailed plans for a post-war order. However, the two Stauffenberg brothers took an “oath” for themselves in which they outlined the main features of their own vision for the future, which was characterised by aristocratic class thinking and the ideals of their “master” Stefan George: “We want a New Order that makes all Germans bearers of the state and guarantees them law and justice, but we despise the lie of equality and bow to the natural ranks.”[54] This elitist attitude was came through in Stauffenberg’s interrogation, as the report of the SS intelligence agency “Security Service of the Reichsführer SS” (Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers SS, SD) states, not without contempt:

“In the opinion of the conspirators, the class of the nobility and the intelligent bourgeoisie called to leadership has been replaced by National Socialism by upstarts, ignorant bawlers without education or upbringing, who are now making use of the power at their disposal in an absolutely selfish and self-centred manner.”[55]

Both brothers spent the night before the assassination attempt in Berthold’s apartment in Berlin and went over the plans one last time. On 17 July, Stauffenberg had already indirectly taken Hermann Mosler into his confidence, who had worked with Stauffenberg and Moltke and belonged to a critical Institute discussion group in which views on the German warfare had been exchanged.[56] After the failed assassination attempt, Berthold von Stauffenberg and his brother were arrested in the Bendlerblock, the headquarters of the Foreign Defence Office. While Claus was executed immediately, Berthold was taken into custody and interrogated by the Gestapo for 21 days. It is not known whether he, like many others, was tortured. On 10 August 1944, he was charged with treason and treachery and sentenced to death by hanging in a show trial by the president of the so-called Volksgerichtshof (“People’s Court”), Roland Freisler. The sentence was carried out on the same day and the “fees” incurred by the execution were charged to the bereaved.[57] The families of Claus and Berthold von Stauffenberg were taken into “clan custody”, which meant that their children were sent to orphanages and their wives were imprisoned in concentration camps. They survived the end of the “Third Reich”.

An Early but Cautious Tribute. Berthold von Stauffenberg in the Collective Memory of the Institute

Stauffenberg’s arrest and execution came as a shock to the members of the Institute. The death of Director Viktor Bruns in September 1943 had left the Institute “headless” to a certain extent and, as Rüdiger Hachtmann points out, an atmosphere of “denunciation and mistrust” had developed at the KWI. As early as January 1944, Institute employee Wilhelm Wengler had been denounced by his colleague Herbert Kier for making a defeatist statement and arrested by the Gestapo.[58] Shortly before the assassination attempt, parts of the Institute had been evacuated from Berlin to the surrounding area. After Stauffenberg’s arrest, there were fears of raids and arrests at the KWI, but these failed to materialise.[59] The dismay over the fate of the colleague was quickly overtaken by the events during the end of the war, which were no less dramatic for the Institute, such as the destruction of the Institute’s premises in the Berlin Palace, the destruction of large parts of the library, and the flight of staff from the Red Army.

Nevertheless, Berthold von Stauffenberg was by no means forgotten. As early as 1947, Alexander N. Makarov published an obituary of his former colleague in the journal Friedenswarte, as part of a series entitled “Vanguards of International Understanding and International Law Scholars as Victims of National Socialism”.[60] Hans Wehberg’s request to write the memorial text on Stauffenberg had actually gone out directly to Hermann Mosler, who had delegated it to Makarov.[61] In response to Makarov’s first draft of the text, which was very cautious, he replied that one “should make use of this favourable opportunity to rehabilitate the Institute in a somewhat more pronounced manner than you did in your representation […] of Berthold’s involvement on 20 July. Perhaps you could present the related sentences as facts, not as hearsay. […] Citing Strebel’s or my name as sources seems to me neither necessary nor correct.”[62] Here, Mosler, who made considerable editorial changes to Makarov’s text, skilfully and purposefully used Stauffenberg to restore the Institute’s reputation.

The first public tribute on the part of the Institute as a whole can be found in the first post-war issue of HJIL from 1951. There, six necrologies commemorate those colleagues who had died during the war and the post-war period, including Berthold von Stauffenberg. This early positioning on Stauffenberg cannot be considered a matter of course, given the negative attitude of the general public towards the German resistance and also the disdainful opinion of the then-director of the Institute, Carl Bilfinger, who was himself not at all free from connections to the National Socialist system, towards his former colleague.[63] The obituary was written by HJIL editor Helmut Strebel, who had had a close personal relationship with Stauffenberg. Strebel’s tribute is reserved in terms of political positioning. He does not claim Stauffenberg’s act of resistance for the Institute as a whole and emphasises that “his involvement in the plans to overthrow [the regime] only became known in outlines to a few individuals just before the assassination attempt.” In this, he differs from Alexander N. Makarov, who suggested a greater involvement of the KWI in the resistance’s planning.[64] What both obituaries have in common is that they primarily honour Stauffenberg’s scholarly career, emphasising his PCIJ commentary. They also mention the Locarno essay, but not the one on citizenship.[65] Neither obituary comment on Claus von Stauffenberg’s motivations for the assassination attempt.

Hermann Mosler, who took over the directorship from Carl Bilfinger in 1954, took a similar approach. He, too, declared his allegiance to Berthold von Stauffenberg early on, but avoided any further qualification of the resistance fighter’s motivations. In 1966, he told Karl Josef Partsch that he had given a speech on the tenth anniversary of the assassination attempt in 1954, to students in Frankfurt, as well as on the 20th anniversary in 1964, as director of the Institute to the staff, which he had found significantly more difficult.[66] This reveals an underlying pattern in Mosler’s handling of National Socialist history. While he was not afraid to take a clear stance vis-a-vis the broader scholarly community and the public,[67] he avoided any historical debate within the MPIL.[68] When Mosler did comment on the history of the Institute, he did so as briefly as possible and only at official anniversary events. Mosler’s first public statement on Stauffenberg and the National Socialist era at the Institute was made in 1961 on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Kaiser Wilhelm/Max Planck Society:

“The National Socialist era gradually and increasingly restricted the possibilities for action, but without destroying the scientific objectivity of the work. All employees who rejected the regime owed it to Bruns‘ skill and Schmitz’ unwavering objectivity that they had found refuge and the freedom to develop their scholarship at the Institute. After Bruns’ death, the distress grew. In the first years of the war, the Institute supported, by providing advice and expert opinions, the efforts of academic member Berthold Schenk Graf v. Stauffenberg, who worked on international law issues at the High Command of the Navy, and Graf Helmuth v. Moltke, who worked on the equivalent issues at the High Command of the Wehrmacht, towards a conduct of war in line with international law. Both became victims of the terror measures that followed 20 July 1944. The agreement made with Graf Stauffenberg to make the Institute available to the new Reich government after the overthrow [of the old one] remained unknown to those in power.”[69]

Stauffenberg’s resistance is portrayed by Mosler in a completely unpathetic manner and without associating himself with it. Mosler also omits the political and ideological background of Stauffenberg’s assassination attempt. Yet, elsewhere in his anniversary publication, Mosler does appropriate Stauffenberg by explicitly referring to the significance of his PCIJ commentary of 1934 and placing the work of the Heidelberg Institute in the tradition of the internationalisation of law.[70] Here, he fails to mention that Stauffenberg was very sceptical of the court and considered writing the commentary a chore.

Mosler’s letter on the 20th anniversary of the attempted Hitler assassination[71]

There were various reasons for Mosler’s sober and distanced statement on Stauffenberg’s resistance, which he was to repeat verbatim 14 years later on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Institute.[72] The Director was aware that the “Third Reich” had been viewed in various different ways by different members of the Institute and that not every member of staff had applauded the assassination attempt. Mosler wanted to avoid fundamental and potentially divisive debates on the role of the Institute and its members in the “Third Reich” at all costs. Although he certainly agreed with Stauffenberg’s actions, many of Stauffenberg’s political and ideological views must have remained alien to him. Mosler had known Stauffenberg since he had joined the Institute in 1937 and was aware of his membership in the circle around the poet Stefan George, in which an elitist, often anti-democratic and anti-Western attitude dominated. Hermann Mosler could not and did not want to build on this.

“International Law in Resistance”? Conclusions

At the Institute, the attitude towards Berthold von Stauffenberg remained complex. After his speech on the 50th anniversary of the Institute in 1975, Hermann Mosler never publicly addressed the history of the Institute again; and similarly, his successor Rudolf Bernhardt omitted the period before 1949 and thus Stauffenberg as an Institute member in his 2018 chronicle of the Institute. Other members of the Institute, such as Helmut Strebel, intensively researched Stauffenberg’s life and work and unsuccessfully tried to win over the directors for this topic.[73] Hermann Mosler in particular avoided linking the Institute with Stauffenberg’s resistance or mobilising Stauffenberg for the rehabilitation of his own discipline. This was only done later, by a number of exponents of German international law of a new generation, who went on to interpret Stauffenberg’s motivation for the assassination attempt as “international law in resistance”.[74] This view materialized within the Institute when, in 1987, during the debate about the Institute’s rebuilding or relocation to Berlin, Theodor Schweisfurth suggested renaming the MPIL “Berthold von Stauffenberg Institute of the Max Planck Society”.[75] Although it never came to that, under the directorship of Jochen Frowein and Rüdiger Wolfrum, the bust of Stauffenberg sculpted by Frank Mehnert was given a more central position in the new Institute building from 1996. Even today, the bust of the young Stauffenberg has a prominent place in the foyer.

The Stauffenberg bust by Frank Mehnert at the main entrance to the MPIL[76]

But the question remains: What does it tell us and what should it tell us today – and what does Stauffenberg stand for today? In the current self-image of the researchers at the Institute, Berthold von Stauffenberg is hardly a historical reference figure against which one would measure one’s own work or attitude – in whatever form. The events of 20 July are too far in the past and have too little impact for that. The views of the resistance in broader society are also undergoing radical change. The strong exaggeration and symbolic charging of individual actors of the resistance movement, especially of 20 July 1944, is considered dishonest today. In liberal, enlightened circles, heroes are no longer necessary as role models for overcoming National Socialist history; we can now face up to the time-bound ambivalence of the protagonists of that period and deal with it. And perhaps this is what Berthold von Stauffenberg conveys to us at the Institute today: the realisation of historical time-boundness and the necessary complexity of our conception of life. But both are also a task for us: Stauffenberg is a reminder of the responsibility of the scholar; he confronts us with the legacy of our burdened history and makes us realise the achievements of liberal democracy and the rule of law. History is complex and dealing with it is not easy. And if it seems easy, it is done wrong. So let us not leave Stauffenberg to those who offer overly simplistic answers in these times but let us take him as an invitation to question ourselves.

***

The author would like to thank Sarah Gebel, Alexandra Kemmerer, Johannes Mikuteit, Moritz Vinken, and Joachim Schwietzke for their helpful annotations to the text.

[1] Hermann Mosler, Staatsrechtslehre und Nationalsozialismus. Vorträge innerhalb der Studium-Generale-Reihe „Wissenschaft und Nationalsozialismus“ im Sommersemester 1966, unpublished typoskript, 3. The author would like to thank Professor Dr. Karl Mosler for providing the text. This and all following direct quotes are translated by the editor, except where indicated otherwise.

[2] Mosler, Staatsrechtslehre (fn. 1), 8; Rudolf Timmermans, Demokratie und Führerstaat: Studien über Begriffe und Formen des Volksstaates, Berlin: Fährmann-Verlag 1936.

[3] Alexander Meyer, Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (1905–1944). Völkerrecht im Widerstand, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2001, 261–262; Wolfgang Graf Vitzthum, Der stille Stauffenberg. Der Verschwörer, Georgeaner und Völkerrechtler Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2024, 152–153.