Deutsch

Das Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht und die Sowjetunion waren praktisch Zeitgenossen. Die Sowjetunion wurde am 30. Dezember 1922 gegründet, das Kaiser‑Wilhelm‑Institut (KWI) nur zwei Jahre später. Da Deutschland zwischen Westeuropa und Russland liegt, war man in Berlin immer auch interessiert daran, wie im Osten Völkerrecht praktiziert und gedacht wurde. Das russische Kaiserreich und später die Sowjetunion haben das weltpolitische Schicksal Deutschlands mehrmals mitbestimmt. Das akademische Interesse am sowjetischen Völkerrecht war somit ernsthaft und keineswegs nur theoretisch: die praktische Relevanz des Forschungsgegenstandes war evident.

In den unterschiedlichen Tätigkeitsfeldern und Entwicklungsphasen des Instituts haben die sowjetische Praxis und Theorie des Völkerrechts die Berliner und später Heidelberger Völkerrechtler oft beschäftigt. In den 1920er-1940er Jahren gehörten zum Institut gleich mehrere Wissenschaftler aus dem ehemaligen Zarenreich: Alexander Makarov (1888-1973), Georg von Gretschaninow (1892-1973), aber auch der Sohn des berühmten russischen Völkerrechtlers Friedrich Martens, Nikolai von Martens (1880-1947). Makarov beispielsweise hat mehrmals in der Haager Akademie Vorlesungen gehalten – vor allem zum internationalen Privatrecht, auch zu dem der UdSSR, die viele alte („bürgerliche“) Rechtsgrundsätze, vor allem bezüglich des Privateigentums, abgelehnt und abgeschafft hatte. Auch in den deutschen Völkerrechtszeitschriften kommentierte Makarov mehrmals die Völkerrechtsentwicklungen in und bezüglich der Sowjetunion – unter anderem, als die Sowjetunion die drei baltischen Staaten Estland, Lettland und Litauen im August 1940 völkerrechtswidrig eingliederte. Die Geheimprotokolle des Hitler-Stalin-Paktes vom 23. August 1939 waren damals noch nicht öffentlich bekannt.

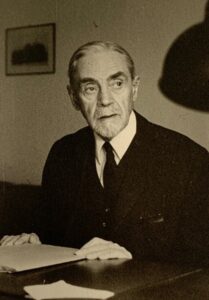

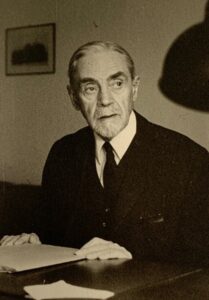

Alexander N. Makarov (undatiert)[1]

In den 1920er und 1930er Jahren entwickelte sich ein Sondergebiet der Rechtswissenschaft in Deutschland – das Ostrecht. Dieses Forschungsgebiet wurde vom KWI in Berlin kaum als besonders ausgewiesener Forschungsschwerpunkt bearbeitet, hier war das Osteuropa-Institut in Breslau (heute Wroclaw in Polen) führend im deutschsprachigen Raum. Es waren auch meistens Juristen, die im ehemaligen Zarenreich geboren waren, die in den deutschen Forschungsinstituten im Ostrecht führend waren. Zum Beispiel kamen sowohl Axel Freytagh‑Loringhoven (der Leiter des Breslauer Instituts) als auch Boris Meissner (in der Nachkriegszeit Leiter des Kölner Instituts für Ostrecht) aus Estland, dem kleinen Nachfolgestaat des Zarenimperiums an der Ostsee. Meistens hatten diese Professoren wenig Illusionen über das Wesen und die juristische Praxis der Sowjetunion, aber sorgfältig erforscht wurde das juristische Geschehen dennoch. Das KWI hat aber auch bis 1933 mit Jacob Robinson (1889-1977), einem jüdischen Rechtswissenschaftler aus Litauen, der durch seine Forschung des Minderheitenproblems bekannt wurde, zusammengearbeitet.

‘Ostrechtsforschung‘ am MPIL: Theodor Schweisfurth und die sowjetmarxistische Theorie vom Völkerrecht ‚neuen Typs‘

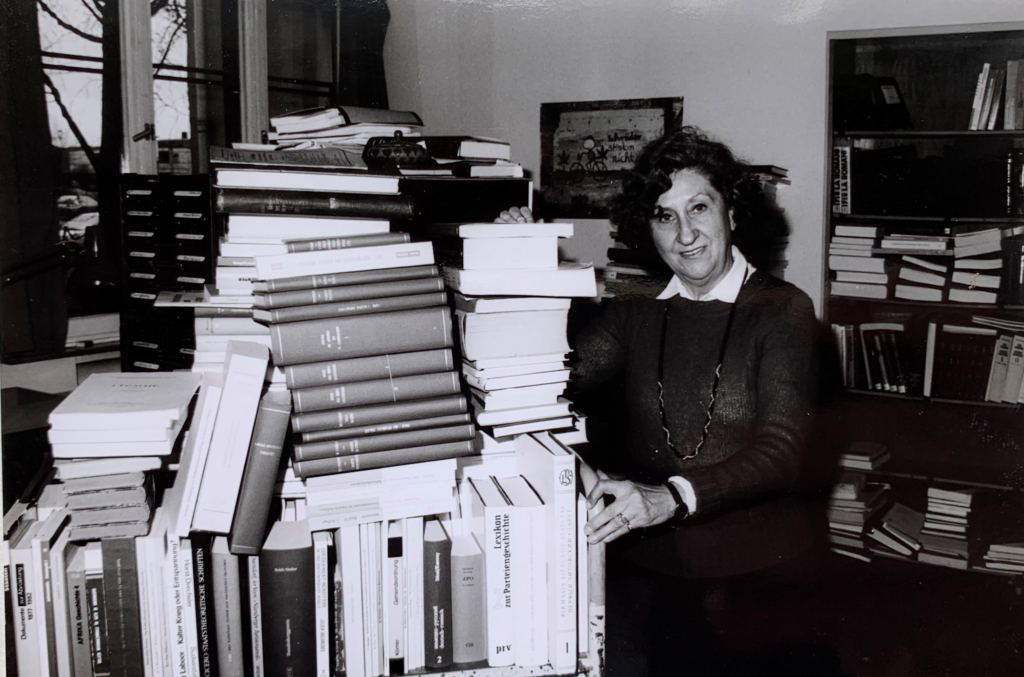

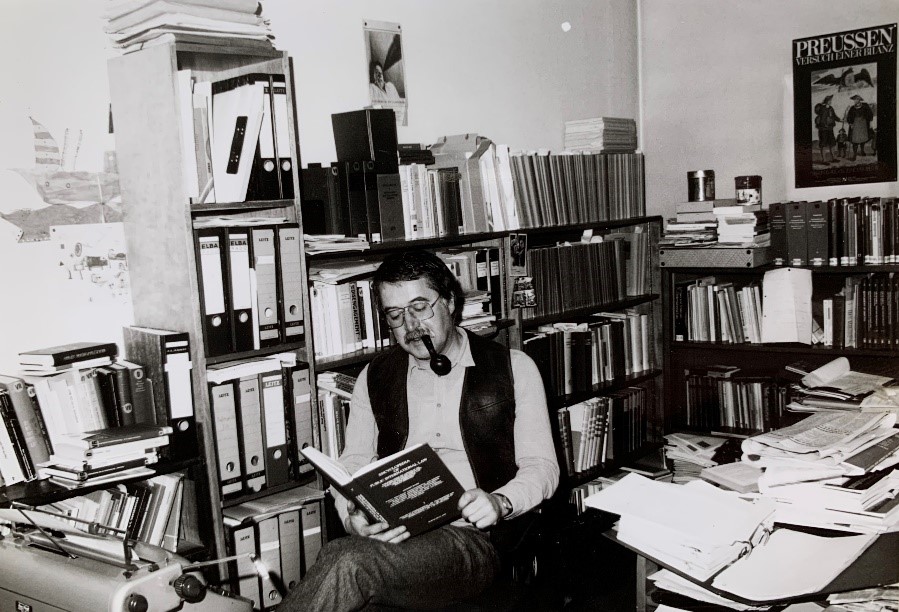

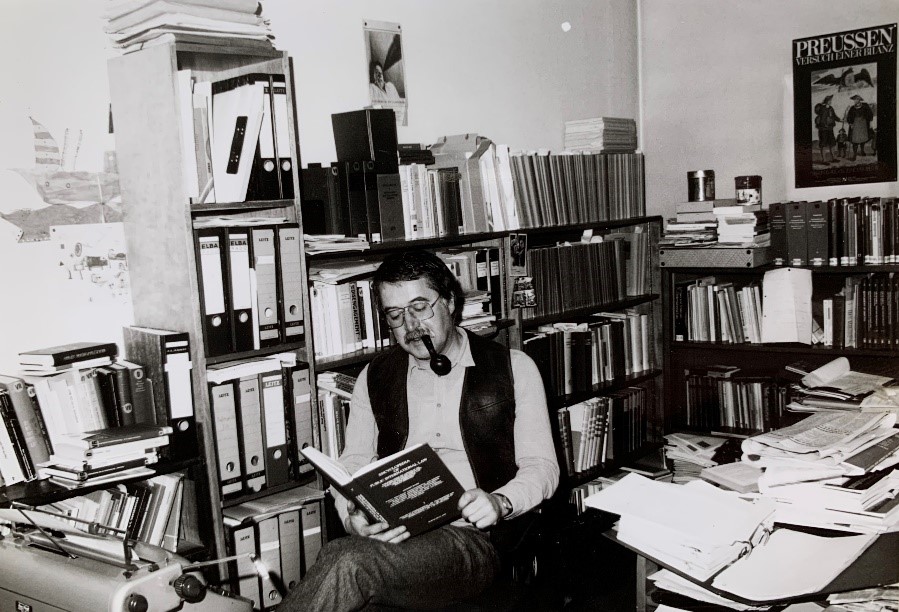

Theodor Schweisfurth in seinem Büro, 1985 [2]

Eines der besten deutschsprachigen wissenschaftlichen Werke zur Theorie des Völkerrechts in der Sowjetunion entstand jedoch am Heidelberger MPIL. Im Jahre 1979 erschien in der Schwarzen Reihe Theodor Schweisfurths Monografie Sozialistisches Völkerrecht? Darstellung – Analyse – Wertung der sowjetmarxistischen Theorie vom Völkerrecht ’neuen Typs’.[3] Das Manuskript wurde als Habilitationsschrift an der Universität Köln verteidigt und vom bereits erwähnten Boris Meissner akademisch betreut. Schweisfurth war aber auch von 1973 bis 1993 am Heidelberger MPIL tätig. Die Hauptfrage, die er in seinem Buch stellt, ist, ob die sowjetische Doktrin des besonderen sozialistischen Völkerrechts ernst zu nehmen sei und welche Bedeutung sie habe. Schweisfurth hatte hierzu in Moskau in sowjetischen wissenschaftlichen Bibliotheken arbeiten können und war insofern fachlich sehr gut vorbereitet. Schweisfurth zeigt in seinem Buch überzeugend, wie die sowjetische Völkerrechtsdoktrin im Grunde immer die Bedürfnisse der sowjetischen Außenpolitik gestützt hat. Als sich die territorialen und machtpolitischen Bedürfnisse Moskaus mit der Zeit änderten, habe meistens auch die völkerrechtliche Doktrin reagiert und sich dementsprechend geändert. Schweisfurth ist sehr gut gelungen, das Wesen der Theorie des ’sozialistischen Völkerrechts’ mit der Hegemoniebildung der Sowjetunion in Ost- und Mitteleuropa zu verknüpfen. Der realpolitische Kern des ’sozialistischen Völkerrechts’ bestand darin, dass die völkerrechtliche Theorie der Sowjetunion es ermöglichte, deren militärische Interventionen in Ungarn (1956) und in der Tschechoslowakei (1968) irgendwie zu rechtfertigen. Für die sozialistischen Staaten galt ein besonderes Völkerrecht – das sozialistische Völkerrecht – das (aus sowjetischer Sicht) nicht nur Vorrang hatte gegenüber den Normen des universellen Völkerrechts, sondern auch Pflichten beinhaltete. Insbesondere galt die gemeinsame Verpflichtung, zu vermeiden, dass ein sozialistischer Staat in den Kapitalismus ‚zurückfallen‘ könnte. Mit den Normen des universellen Völkerrechts (UN-Charta) waren diese sowjetische Praxis und die damit verbundenen Hegemonieansprüche aber kaum vereinbar, was auch die Konkurrenten der UdSSR, damals sehr deutlich die Volksrepublik China, immer betont haben.

Deutsch-sowjetische Forschungskooperation: die Völkerrechtskolloquien der 1980er Jahre

Ein besonderes Kapitel in der Geschichte des MPIL sind die sowjetisch-deutschen völkerrechtlichen Kolloquien. Die erste dieser Veranstaltungen fand vom 5. bis 10. Juli 1982 in Heidelberg statt; danach wurden sie etwa alle zwei Jahre abwechselnd in der UdSSR (meistens in Moskau) und in Deutschland abgehalten. Mein späterer Doktorvater an der Humboldt‑Universität zu Berlin, damals noch Professor in Bonn, Christian Tomuschat, konnte am ersten Kolloquium nicht teilnehmen. Er drückte in einem persönlichen Brief gegenüber dem Institutsdirektor Rudolf Bernhardt die Hoffnung aus, dass beim Kolloquium ein erfreuliches Arbeitsklima geherrscht habe:

„Auch Sowjetmenschen sind ja letzten Endes von innerer Freude durchdrungen, wenn sie für eine kleine Weile aus dem sozialistischen Paradies verstoßen werden und die Erniedrigung des Menschen im kapitalistischen System auf sich nehmen müssen.“[4]

Das zweite gemeinsame Völkerrechtskolloquium fand schon vom 16. bis 22. Oktober 1984 in Moskau und Leningrad (heute: Sankt Petersburg) statt. Es waren nicht nur führende sowjetrussische Völkerrechtler wie Grigori Tunkin dabei, sondern auch Völkerrechtler, die symbolisch die sonstigen Sowjetrepubliken vertreten sollten – Levan Aleksidze (Georgien), Igor Lukashuk (Ukraine) und Rein Müllerson (Estland). Wilhelm Karl Geck, ein deutscher Teilnehmer schrieb nach dem Kolloquium dem MPIL-Direktor Rudolf Bernhardt in einem persönlichen Brief vom 26. September 1984 anerkennend:

„Für Sie war die Sache ja auch deshalb besonders anstrengend, weil Sie auf die verschiedenen Reden der sowjetischen Herren reagieren mussten, was bei den obwaltenden Umständen nicht ganz einfach war. Auch im Rückblick glaube ich, dass sich die deutsche Seite gut gehalten hat: Ohne dezidiertes Eingehen auf Details bei sowjetischen Angriffen kam der grundsätzlich andere Standpunkt in wesentlichen Facetten zum Ausdruck.“

Wenn man die sowjetischen Jahrbücher für Völkerrecht der frühen 1980er Jahre (Herausgeber: Grigori Tunkin) durchblättert, sieht man, dass der Kalte Krieg in vollem Gange und die ideologische Gegnerschaft, auch auf dem Gebiet der Völkerrechtstheorie, erbittert war. In seinem 2012 publizierten Tagebuch zählt Tunkin auf, wer von den deutschen Völkerrechtlern dabei war als er das MPIL in Heidelberg besuchte und dort eine Vorlesung hielt; insbesondere erwähnt er auch seine „reaktionären“ Gegner – vor allem Boris Meissner.[5]

Das dritte Kolloquium fand vom 4. bis 8. Mai 1987 in Kiel statt. Bei den ersten beiden Kolloquien war es um diverse Themen des Völkerrechts gegangen, aber jetzt war es wohl der Einfluss des späteren MPIL-Direktors Rüdiger Wolfrum, der dafür sorgte, dass man sich für ein genauer umrissenes Generalthema entschied: Völkerrecht und Landesrecht. Aus dem Kolloquium ist auch ein Sammelband entstanden.[6]

Man kann sich fragen, was die DDR-Völkerrechtler(innen) von den deutsch‑sowjetischen Kolloquien gedacht haben mögen und ob sie so etwas wie eine gewisse politisch‑wissenschaftliche Eifersucht empfunden haben. Führende DDR-Völkerrechtler, wie zum Beispiel Bernhard Graefrath und Peter Alfons Steiniger, hatten wohl keinen Grund, in einer möglichen Annäherung der sowjetischen und westlichen Positionen etwas eindeutig Positives für die DDR zu sehen. Sicherlich hat auch nicht jeder Völkerrechtler in der Sowjetunion mit Freude auf die Kolloquien geblickt – so erschien beispielsweise 1986 in Moskau das kritische Buch des sowjetischen Völkerrechtlers Vladimir Pustogarov mit dem Titel Der westdeutsche Revanchismus und das Völkerrecht.[7]

Die deutsch-sowjetischen Völkerrechtskolloquien gaben den deutschen Teilnehmern die Gelegenheit, von der ersten Reihe aus mitzusehen, wie sich die sowjetische Gesellschaft im Rahmen der Perestroika veränderte. Manche Teilnehmer (Rainer Hofmann)[8] erinnern, wie sich die Machtdynamik und Kraftverhältnisse innerhalb der sowjetischen Delegationen mit der Zeit wandelten und dass die jüngeren sowjetischen Völkerrechtler später den älteren manchmal auch widersprachen, was zuvor wohl unerhört gewesen wäre, zumindest vor den westlichen Kollegen.

Vom 29. Mai bis 4. Juni 1989 traf man sich für ein Kolloquium abermals in Moskau– wobei die Deutschen im „Hotel Ukraina“ unterkamen und ihr Mittagessen im „Restaurant Praha“ einnahmen (Moskau war noch immer die Hauptstadt eines Imperiums!). Knapp ein Jahr später kam die Wiedervereinigung Deutschlands im Oktober 1990.

Kurz vor dem Zusammenbruch der Sowjetunion traf man sich ein letztes Mal in Heidelberg. Vom 17. Bis 18. Oktober 1991 setzte man sich mit dem Thema Föderalismus-Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit auseinander. In ihrer hochinteressanten Monografie Die Konzepte ’staatliche Einheit’ und ’einheitliche Macht’ in der russischen Theorie von Staat und Recht zeigt Caroline von Gall, dass manche russische juristische Autoren den Deutschen später vorwarfen, die Ideologie des Föderalismus, die damals propagiert wurde, habe den machtpolitischen Interessen Russlands geschadet[9]. Mit dem Scheitern eines echten Föderalismus war aber auch die Entscheidung getroffen, dass die russländische Föderation auch nach der Sowjetunion weiterhin ein Quasi-Imperium bleiben sollte, mit allem Negativen, was daraus resultiert, sowohl für die Nachbarstaaten als auch für politisch andersdenkende Russen.

Das Interesse an Russland und dem dortigen Völkerrecht lebt auch heute fort am MPIL – vor allem in der wissenschaftlichen Arbeit von Matthias Hartwig[10], der inzwischen in den Ruhestand eingetreten ist, aber weiter am Institut forscht. Auch jüngere Völkerrechtler am MPIL haben zu diesem Thema interessante Forschung beigetragen.[11] Im Vergleich zu den früheren Jahrzehnten scheint aber die Erforschung der völkerrechtlichen Theorie und Praxis im Osten heutzutage keine strategische Priorität zu sein – was vielleicht, wenn man unter anderem den jetzigen Krieg Russlands gegen Ukraine betrachtet, ein Versäumnis sein könnte.

Das MPIL hat die Sowjetunion überlebt. Ob es aber die besseren völkerrechtlichen Argumente der Deutschen waren, die am Ende auch die sowjetischen Völkerrechtler überzeugten, oder die besseren Konsumgüter im Westen (oder im Kapitalismus), darüber kann man streiten.

***

Der Autor dankt Philipp Glahé und Alexandra Kemmerer für den Zugang zu den Archiven im MPIL, betreffend die Planung und Durchführung der sowjetisch-deutschen Kolloquien.

[1] Foto: MPIL.

[2] Foto: MPIL.

[3] Theodor Schweisfurth, Sozialistisches Völkerrecht? Darstellung – Analyse – Wertung der sowjetmarxistischen Theorie vom Völkerrecht ‚neuen Typs‘, Berlin: Springer 1979.

[4] Schreiben von Christian Tomuschat an Rudolf Bernhardt, datiert 12. Juli 1982, Ordner “Deutsch-Sowjetisches Kolloquium”, MPIL Archiv.

[5] William Elliott Butler (Hrsg.) The Tunkin Lectures: The Diary and Collected Lectures of G. I. Tunkin at the Hague Academy of International Law, Den Haag: Eleven International Publishing 2012.

[6] J. Enno Harders/Grigory I. Tunkin/Rüdiger Wolfrum (Hrsg.), International Law and Municipal Law. Proceedings of the German-Soviet Colloqui on International Law at the Institut für Internationales Recht an der Universität Kiel, 4 to 8 May 1987, Berlin: Duncker und Humblot 1988.

[7] Vladimir V. Pustogarov, Zapadno-germanskii revanshizm i mezhdunarodnoe pravo, Moskau: Nauka, 1986.

[8] Persönliches Gespräch bei der Jahrestagung von American Society of International Law, am 6. April 2024.

[9] Caroline von Gall, Die Konzepte ’staatliche Einheit’ und ’einheitliche Macht’ in der russischen Theorie von Staat und Recht. Der Einfluss des Gemeinschaftsideals auf die russische Verfassungsentwicklung, Berlin: Duncker und Humblot 2010.

[10] Siehe z.B.: Matthias Hartwig, Vom Dialog zum Disput? Verfassungsrecht vs Europäische Menschenrechtskonvention. – Der Fall der Russländischen Föderation, Europäische Grundrechtezeitschrift 44 (2017), 1-23.

[11] Siehe z.B.: Christian Marxsen, The Crimea Crisis. An International Law Perspective, ZaÖRV 74 (2014), 377-391.

English

The Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law and the Soviet Union were practically contemporaries. The Soviet Union was founded on 30 December 1922, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (KWI) only two years later. As Germany is located between Western Europe and Russia, in Berlin, one was always interested in how international law was practiced and thought about in the East. After all, the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union helped determine Germany’s global political fate on several occasions. Academic interest in Soviet international law was therefore serious and by no means merely theoretical: the practical relevance of the subject was evident.

In the various fields of activity and phases of development of the Institute, Soviet practice and theory of international law often occupied the international law scholars in Berlin and later Heidelberg. In the 1920s-1940s, the Institute housed several academics from the former Tsarist Empire: Alexander Makarov (1888‑1973), Georg von Gretschaninow (1892‑1973), but also the son of the famous Russian international law expert Friedrich Martens, Nikolai von Martens (1880‑1947). Makarov, for example, gave several lectures at the Hague Academy – above all on private international law, including that of the USSR, which had rejected and abolished many old (“bourgeois”) legal principles, especially with regard to private property. Makarov also commented several times in German international law journals on developments in international law in and concerning the Soviet Union – including when the Soviet Union annexed the three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in August 1940 in violation of international law. The secret protocols of the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 23 August 1939 were not yet known to the public at the time.

Alexander N. Makarov[1]

In the 1920s and 1930s, a novel field of legal research developed in Germany – ‘East European Law’ (Ostrecht). The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin hardly focused on this field as a special research area. Here, the Osteuropa-Institut in Breslau (now Wroclaw in Poland) was the leading‑edge in the German‑speaking world. It was also mostly lawyers who were born in the former Tsarist Empire who premiered in the German research institutes in East European law. For example, both Axel Freytagh‑Loringhoven (director of the Breslau Institute) and Boris Meissner (director of the Cologne Institute for East European Law in the post-war period) came from Estonia, the small successor state to the Tsarist Empire on the Baltic Sea. For the most part, these professors had few illusions about the nature and legal practice of the Soviet Union, but the legal developments were nevertheless researched carefully. Until 1933, the KWI also collaborated with Jacob Robinson (1889-1977), a Jewish legal scholar from Lithuania who became famous for his research into minority issues.

‘East European Law Research’ at the MPIL: Theodor Schweisfurth and the Soviet-Marxist Theory of a ‘New Type’ of International Law

Theodor Schweisfurth in his office, 1985[2]

However, one of the best German-language academic works on the theory of international law in the Soviet Union was written at the Heidelberg MPIL. In 1979, Theodor Schweisfurth’s monograph Sozialistisches Völkerrecht? Darstellung – Analyse – Wertung der sowjetmarxistischen Theorie vom Völkerrecht ’neuen Typs’ („Socialist International Law? Description – Analysis – Evaluation of the Soviet‑Marxist Theory of ‘New Type’ International Law”)[3] was published. The manuscript was defended as a habilitation thesis at the University of Cologne and academically supervised by the aforementioned Boris Meissner. Schweisfurth worked at the Heidelberg MPIL from 1973 to 1993. The main question that he poses in his book is whether the Soviet doctrine of a novel socialist international law should be taken seriously and what significance it has. Schweisfurth had been able to work on this in Soviet academic libraries in Moscow and was therefore very well informed in this respect. In his book, Schweisfurth convincingly shows how the Soviet doctrine of international law has essentially always supported the needs of Soviet foreign policy. When Moscow’s territorial and power-political needs changed over time, the doctrine of international law usually reacted and changed accordingly. Schweisfurth succeeded in linking the essence of the theory of ‘socialist international law’ with the formation of Soviet hegemony in Eastern and Central Europe. In terms of Realpolitik, ‘socialist international law’ allowed the Soviet Union to somehow justify its military interventions in Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968). According to Soviet doctrine, the socialist states were subject to a novel international law – socialist international law – which (from the Soviet perspective) not only took precedence over the norms of universal international law but also contained obligations: in particular, the common obligation to prevent a socialist state from ‘falling back’ into capitalism. However, this Soviet practice and the associated claims to hegemony were hardly compatible with the norms of universal international law (UN Charter), which the USSR’s competitors – very noticeably at that time, the People’s Republic of China – continually emphasised.

German-Soviet Research Co-operation: the International Law Colloquia of the 1980s

A significant chapter in the history of the MPIL are the Soviet-German Colloquia on International Law, the first of which took place in Heidelberg from 5 to 10 July 1982. Afterwards, they were held alternately in the USSR (usually in Moscow) and in Germany approximately every two years. Christian Tomuschat, who would later be my doctoral supervisor at the Humboldt University in Berlin, then still a professor in Bonn, was unable to attend the colloquium. In a personal letter to the director of the MPIL, Rudolf Bernhardt, he expressed the hope that a pleasant working atmosphere had prevailed at the colloquium:

“Even Soviet people are ultimately imbued with inner joy when they are cast out of socialist paradise for a little while and have to accept the abasement of human beings in the capitalist system.” [4]

The second joint colloquium on international law took place from 16 to 22 October 1984 in Moscow and Leningrad (today: Saint Petersburg). It was attended not only by leading Soviet‑Russian international law experts such as Grigori Tunkin, but also by international law experts who were to symbolically represent the other Soviet republics – Levan Aleksidze (Georgia), Igor Lukashuk (Ukraine) and Rein Müllerson (Estonia). Wilhelm Karl Geck, a German participant, expressed his approval to MPIL director Rudolf Bernhardt after the colloquium, in a personal letter from 26 September 1984:

“For you, the matter was surely particularly strenuous because you had to react to the various speeches by the Soviet gentlemen, which was not easy in the prevailing circumstances. Even in retrospect, I believe that the German side held up well: Without detailed rebuttal of Soviet attacks, the fundamentally different point of view was expressed in its essential facets.”

Leafing through the Soviet Yearbooks of International Law from the early 1980s (edited by Grigori Tunkin), it is obvious that the Cold War was in full swing and ideological conflict was fierce, also in the field of international law theory. In his diary, published in 2012, Tunkin lists which German international lawyers were present when he visited the MPIL in Heidelberg and gave a lecture there; in particular, he mentions his ‘reactionary’ opponents – above all Boris Meissner. [5]

The third colloquium took place in Kiel from 4 to 8 May 1987. The first two colloquia had dealt with various topics of international law, but now it was probably the influence of the later MPIL director Rüdiger Wolfrums that led to the decision in favour of a more precisely defined overarching topic: International Law and Municipal Law. The colloquium also resulted in an anthology.[6]

One might ask oneself what the international law experts of the GDR may have thought of the German-Soviet Colloquia and whether they felt something like a political or scientific jealousy. Leading GDR international law experts, e.g. Bernhard Graefrath and Peter Alfons Steiniger, likely had no reason to see a possible convergence of Soviet and Western positions as something clearly positive for the GDR. Likewise, certainly not every international law expert in the Soviet Union looked forward to the colloquia – for example, Soviet international law expert Vladimir Pustogarov published a critical book entitled ‘West German Revanchism and International Law’ in 1986.[7]

The German-Soviet Colloquia on International Law gave the German participants the opportunity to observe from the front row how Soviet society changed in the context of perestroika. Some participants (Rainer Hofmann)[8] recall how the power dynamics and relations within the Soviet delegations changed over time and that the younger Soviet international law experts would in later years sometimes contradict their older counterparts, which would probably have been unheard of in the past, at least in front of Western colleagues.

From 29 May to 4 June 1989, another colloquium was held in Moscow – where the Germans stayed in the “Hotel Ukraina” and had lunch in the “Restaurant Praha” (Moscow was still the capital of an empire!). Less than a year later came the reunification of Germany in October 1990.

The last colloquium, shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union took place from 17 to 18 October 1991in Heidelberg. Here, one discussed the topic of Federalism – Constitutional Jurisdiction. In her highly interesting monograph Die Konzepte ’staatliche Einheit’ und ’einheitliche Macht’ in der russischen Theorie von Staat und Recht (“The concepts of ‘state unity’ and ‘unitary power’ in the Russian theory of state and law”), Caroline von Gall shows that some Russian legal scholars later denounced the Germans because the ideology of federalism, propagated at the time, had supposedly harmed Russia’s power-political interests[9] . With the failure of genuine federalism, however, the decision was also made that the Russian Federation, even after the Soviet Union, would remain a quasi-empire with all the negative consequence this entails, both for the neighbouring states and for Russians with differing political views.

The interest in Russia and its international law lives on at the MPIL even today – especially in the academic work of Matthias Hartwig[10] , who has recently retired but continues to conduct research at the institute. Younger international law scholars at the MPIL have also contributed interesting research on this topic.[11] Compared to earlier decades, however, research into the theory and practice of international law in the East does not seem to be a strategic priority these days – which may be an omission, considering Russia’s current war against Ukraine, among other things.

The MPIL survived the Soviet Union. But whether it was the Germans’ better international law arguments that ultimately convinced the Soviet international law experts or rather better consumer goods in the West (or in capitalism) is debatable.

***

The author would like to thank Philipp Glahé and Alexandra Kemmerer for their kind support in accessing the archives at the MPIL with regard to the planning and organisation of the Soviet‑German Colloquia.

Translation from the German original: Sarah Gebel

[1] Photo: MPIL.

[2] Photo: MPIL.

[3] Theodor Schweisfurth, Sozialistisches Völkerrecht? Darstellung – Analyse – Wertung der sowjetmarxistischen Theorie vom Völkerrecht ‚neuen Typs‘, Berlin: Springer 1979.

[4] Letter by Christian Tomuschat to Rudolf Bernhardt, dated 12 July 1982, Folder “Deutsch-Sowjetisches Kolloquium”, MPIL Archive, translated by the editor.

[5] William Elliott Butler (ed.) The Tunkin Lectures: The Diary and Collected Lectures of G. I. Tunkin at the Hague Academy of International Law, The Hague: Eleven International Publishing 2012.

[6] J. Enno Harders/Grigory I. Tunkin/Rüdiger Wolfrum (eds), International Law and Municipal Law. Proceedings of the German-Soviet Colloqui on International Law at the Institut für Internationales Recht an der Universität Kiel, 4 to 8 May 1987, Berlin: Duncker und Humblot 1988.

[7] Vladimir V. Pustogarov, Zapadno-germanskii revanshizm i mezhdunarodnoe pravo, Moscow: Nauka, 1986.

[8] Personal conversation at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of International Law, 6 April 2024.

[9] Caroline von Gall, Die Konzepte ’staatliche Einheit’ und ’einheitliche Macht’ in der russischen Theorie von Staat und Recht. Der Einfluss des Gemeinschaftsideals auf die russische Verfassungsentwicklung, Berlin: Duncker und Humblot 2010.

[10] See e.g.: Matthias Hartwig, Vom Dialog zum Disput? Verfassungsrecht vs Europäische Menschenrechtskonvention. – Der Fall der Russländischen Föderation, Europäische Grundrechtezeitschrift 44 (2017), 1-23.

[11] See e.g.: Christian Marxsen, The Crimea Crisis. An International Law Perspective, HJIL 74 (2014), 377-391.

Lauri Mälksoo is Professor of International Law at the University of Tartu in Estonia.