Berlin under National Socialism, 1937 (Picture: Creative Commons)

Deutsch

Carl Schmitt, Viktor Bruns und das KWI für Völkerrecht

Am 2. November 1933 schreibt der Vorsitzende des Kuratoriums „an die Herren Mitglieder des Instituts für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht e. V.“:

„Der Direktor des Instituts für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht e. V., Herr Geheimer Justizrat Professor Dr. Bruns hat beantragt, den zum ordentlichen Professor an der Juristischen Fakultät der Universität Berlin ernannten Herrn Staatsrat Professor Dr. Carl Schmitt zum wissenschaftlichen Berater des Instituts zu wählen. Der Herr Institutsdirektor hat zur Begründung seines Antrages noch folgendes angeführt:

‚Die Stellung, die Herr Professor Dr. Carl Schmitt in der Wissenschaft seines Faches einnimmt, macht eine Begründung dieses Antrags überflüssig. Ich möchte lediglich darauf hinweisen, welche große Bedeutung der Gewinn dieses Gelehrten für die Arbeit des Instituts zukommt [sic!], der in hervorragendem Maße an der Vorbereitung neuer Gesetze[1] beteiligt ist. Es ist zu erwarten, daß durch seine Person die Arbeit des Instituts auf staatsrechtlichem Gebiet in den unmittelbaren Dienst praktischer Staatsaufgaben gestellt werden wird. Es entspricht dies den Zielen und Aufgaben, die sich das Institut von seiner Gründung an gesetzt hat, und die es seither besonders auf dem Gebiete des Völkerrechts zu verwirklichen berufen war.‘

Ich stelle diesen Antrag gemäß § 5 der Satzungen des Instituts zur Abstimmung.

Sollte ich bis zum 15. d. Mts. mit einer Antwort nicht beehrt sein, so nehme ich an, daß die Herren Kuratoriumsmitglieder mit dem Vorschlag einverstanden sind.“

Carl Schmitt hatte am 8. September seine Annahme des Rufes nach Berlin erklärt und Viktor Bruns wenige Tage später, am 18. September, „sehr freundlich“[2] im Hotelzimmer getroffen. Vielleicht besprachen sie damals seine Anbindung als „Berater“ am Institut. Am 5. November, also wenige Tage nach dem Schreiben des Kuratoriumsvorsitzenden, notiert Schmitt nach einer „Sitzung der Akademie für Deutsches Recht“ dann ein Treffen mit Bruns und Richard Bilfinger im Fürstenhof. Auf der Sitzung hielt Bruns einen Vortrag über „Deutschlands Gleichberechtigung als Rechtsproblem“.[3] In seiner völkerrechtlichen Programmschrift „Nationalsozialismus und Völkerrecht“ schreibt Schmitt zum Vortrag: „Unser Anspruch auf Gleichberechtigung ist kürzlich noch von Viktor Bruns in einer geradezu klassischen Weise nach seinen verschiedenen juristischen Stellen hin dargelegt worden.“[4] Nur sehr selten zitierte er Publikationen von Bruns. Die positive Erwähnung einer ausgewogenen juristischen Analyse ist auch etwas vergiftet; in anderen Zusammenhängen hätte Schmitt vielleicht abschätziger von liberalem, diplomatisch zurückhaltendem Positivismus gesprochen. Ende 1933, als Schmitt gerade in Berlin in seiner neuen Rolle als „Kronjurist“ ankommt, scheint der Kontakt mit Bruns jedenfalls besonders intensiv und positiv zu sein. Kehren wir hier zum Schreiben des Kuratoriumsvorsitzenden zurück, so verwundert es im November 1933 geradezu, dass noch satzungsgemäß gewählt wurde, wurde die Universitätsverfassung doch gerade auf das „Führerprinzip“ umgestellt. Die Wahl ist auch förmlich fragwürdig, da nur eine Frist zum Einspruch gestellt ist, für einen Antrag, der seine Begründung für „überflüssig“ erklärt und selbstverständlich von Zustimmung ausgeht. Waren alle Mitglieder des Instituts wahlberechtigt oder nur die Kuratoriumsmitglieder, wie es anklingt? Wurde ein Abstimmungsergebnis festgestellt? Was versprach sich Bruns damals eigentlich von der Ersetzung Erich Kaufmanns durch Schmitt? Erwartete er eine Intensivierung des rechtspolitischen Einflusses auf das „staatsrechtliche Gebiet“? Ging es um eine Loyalitätsgeste oder suchte er das Institut darüber hinaus auch durch den „Staatsrat“ abzusichern und vor Übergriffen zu schützen?

Der „Kronjurist“ am KWI. Eine strategische Wahl?

In den Archiven des MPI finden sich nur wenige Quellen zu Schmitts Beraterfunktion. Schmitt war im Herbst 1933 mit dezidiert „staatspolitischem“ Auftrag aus Köln an die Berliner Universität gewechselt und stand im Zenit seiner nationalsozialistischen Karriere. Er war von Hermann Göring zum Preußischen Staatsrat ernannt worden und kooperierte sein einigen Monaten eng mit dem „Reichskommissar“ und „Reichsrechtführer“ Hans Frank. Auf dem von Adolf Hitler höchstpersönlich eröffneten Deutschen Juristentag, eigentlich der 4. Reichstagung des Bundes Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher Juristen (BNSDJ), hatte er gerade am 3. Oktober eine programmatische Rede zum „Neubau des Staats- und Verwaltungsrechts“[5] gehalten, die „Führertum und Artgleichheit als Grundbegriffe des nationalsozialistischen Rechts“ exponierte und die Institution des neuen Staatsrats als „erste anschauliche und vorbildliche Gestalt“ zur „Errichtung eines Führerrats“ empfahl, auf den der Ehrgeiz des „Kronjuristen“ damals wohl aspirierte.[6]

Schmitt setzte auf einen durchgreifenden Umbau des „totalen Staates“ zum personalistisch integrierten, mehr oder weniger „charismatischen“ „Führerstaat“. Es entspricht seinen Überlegungen, wenn Bruns in seinem leicht verblümten Oktroy schreibt, dass durch dessen „Person die Arbeit des Instituts auf staatsrechtlichem Gebiet in den unmittelbaren Dienst praktischer Staatsaufgaben gestellt“ werde. Wenn Bruns mit spitzer Feder sorgfältig formulierte, klingt eine Unterscheidung zwischen dem wissenschaftlichen Institut und politischen Anwendern an, die als Personen selbstständig agieren und nur als „Berater“ angebunden sind. Was Schmitt für sein Honorar genauer tat, ist noch nicht erforscht und teils wohl auch nicht schriftlich fixiert. Seine institutionelle Einbindung blieb aber auch in den nächsten Jahren relativ schwach. Zwar hatte er Erich Kaufmann, mit dem er seit gemeinsamen Bonner Tagen herzlich verfeindet war, mit schärfster antisemitischer Denunziation aus der Universität vertrieben und dessen Rolle im KWI-Institut übernommen – er wurde auch Mitherausgeber der institutseigenen Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (ZaöRV) -, gehörte aber wohl niemals zum engsten und innersten Kreis der Berater und Mitarbeiter von Bruns. Zwar arbeitete er in den nächsten Jahren ab und an in der Institutsbibliothek, die im Stadtschloss, der Universität benachbart, prächtig residierte, und suchte dort wohl auch das gelegentliche Gespräch, insbesondere mit Heinrich Triepel, zu dessen Hegemonie Schmitt sich in einer eingehenden Besprechung kritisch positionierte;[7] das KWI wurde aber wohl niemals zur bevorzugten Bühne seiner nationalsozialistischen Gleichschaltungsaktivitäten.

So extensiv und intensiv die internationale Schmitt-Forschung auch ist, fehlen ihr gerade für die Zeit nach dem 30. Juni 1934 doch die Quellen zur genauen Beschreibung von Schmitts vielfältigem rechtspolitischen Wirken. Als einfacher Zugang muss hier deshalb die Selbstbeschreibung in Nürnberger Untersuchungshaft von 1947 genügen, auch wenn sie offenbar apologetisch geschönt ist.[8] Der Ankläger Robert Kempner wünschte eine schriftliche Stellungnahme zur Frage, ob Schmitt die „theoretische Untermauerung der Hitlerschen Grossraumpolitik gefördert“ habe. Schmitt verneinte dies ausführlich. Hierbei kam er auch auf seine Rolle am KWI und sein Verhältnis zu Viktor Bruns zu sprechen:

„Ich bin seit 1936 von Niemand, weder von einer Stelle noch von einer Person, weder amtlich noch privat um ein Gutachten[9] gebeten worden und habe auch kein solches Gutachten gemacht, weder für das Auswärtige Amt noch für eine Partei-Stelle noch für die Wehrmacht, die Wirtschaft oder die Industrie. Ich habe auch keinen Rat erteilt, der irgendwie auch nur entfernt mit Hitlers Eroberungs- oder Besatzungspolitik in Zusammenhang stände. […] Ich habe, wie viele andere Rechtslehrer, an mehreren Sitzungen des von Prof. Bruns geleiteten Ausschusses für Völkerrecht der Akademie für Deutsches Recht teilgenommen,[10] habe mich aber dort, auch in Diskussionen, ganz zurückgehalten und nicht den geringsten Einfluss gehabt und gesucht. […] Ich habe während des Krieges kein Amt und keine Stellung übernommen, weder als Kriegsgerichtsrat, noch als Kriegsverwaltungsrat im besetzten Gebiet, noch als Mitglied eines Prisenhofes oder irgend etwas Ähnliches. Es ist mir auch keine solche Stellung angeboten worden, noch habe ich mich darum bemüht. Ich bin nicht einmal Nachfolger von Prof. Bruns in der Leitung des Instituts für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft) geworden, als Prof. Bruns im September 1943 gestorben war. […] Ich habe kein Institut gehabt, bin niemals Rektor oder Dekan geworden.“

Bei den zahlreichen Fehlanzeigen, die er strategisch verzeichnet, verwundert die ihrerseits fast verwunderte Formulierung, er sei „nicht einmal“ Nachfolger von Bruns geworden. War das Amt so unbedeutend? Konnte Schmitt Ende 1943 noch Ansprüche machen, wenn er „seit 1936“ wirklich so ohnmächtig war, wie er glauben machen möchte?

Schmitt und sein Verhältnis zu Viktor Bruns und Carl Bilfinger

Im Mai 1941 äußerte Schmitt sich Rudolf Smend gegenüber über eine der Völkerrechts-Ausschusssitzungen; er nannte diesen „Auftrieb“ eine der „Erniedrigungen der reinen Wissenschaft“ und führte aus:

„Zu sehen, wie Professoren sich hochgeehrt fühlen, wenn sie jüngeren Referenten oder auch alten aus dem Ministerium lauschen dürfen, ist sehr traurig. Wenn dann noch eine von Bruns geleitete ‚Diskussion‘ eintritt, in der Herr Thoma, Herr Bilfinger und ein ebenso alter Herr von Düngern [sic!] bahnbrechende Konstruktionen – unter Dankesbezeugungen, daß ihnen eine so auszeichnende Erlaubnis zuteil wurde – an die Adresse seiner hohen Behörden vortragen, dann sehnt man sich nach der Mansarde.“[11]

Dass Schmitt sich 1941 so despektierlich über Richard Thoma, Bruns und Bilfinger äußerte, ist einigermaßen überraschend. Schmitt bezieht sich auf eine Sitzung vom 2. Mai 1941 zum Tagungspunkt „Landkriegsordnung“. Conrad Roediger trug über das „kodifizierte Landrecht im gegenwärtigen Krieg“ vor. Richard Thoma sprach dazu in einem längeren Statement über die Geltung des Völkerrechts im Generalgouvernement, also im Machtbereich Hans Franks. Thoma fragte danach, wie man „eine Übereinstimmung des Vorgehens der deutschen Regierung in diesem völlig überwundenen Gebiet mit dem Völkerrecht durchführen kann“.[12] Er meinte, es ließe ich nicht mit der occupatio bellica argumentieren, sondern nur mit der offenen Erklärung, dass die „Besetzung mit der intentio der völligen Zerstörung des besiegten Feindes“ erfolgt. Thoma mahnte also das Völkerrecht und eine offene Erklärung des nationalsozialistischen Extremismus an. Otto von Dungern widersprach umgehend im nationalsozialistischen Sinn, Bruns beendete als Vorsitzender dann sofort die Diskussion. Eine Stellungnahme Schmitts, des Autors der „Wendung zum diskriminierenden Kriegsbegriff“, ist nicht verzeichnet. Sein Brief an Smend setzt Thoma also herab, indem er ihn mit von Dungern assoziiert, obgleich, oder eben weil, Thoma die konträre Position vertrat und an das Völkerrecht im Generalgouvernement erinnerte. Schmitts Polemik lässt zweifeln, dass er einen „klassischen“ Kriegsbegriff vertrat. Er tabuisierte die offene Rede über die Kriegsverbrechen in Franks Generalgouvernement. Dass er Smend gegenüber brieflich gegen Thoma polemisierte, verwundert bei seiner politischen Differenz zu Smend nicht. Eher überraschen die negativen Bemerkungen zu Bilfinger und Bruns.

Zuvor hatte er mit allen Dreien vergleichsweise freundliche Beziehungen gepflegt. Bilfinger muss sogar als einer seiner engsten Weggefährten und Mitstreiter bezeichnet werden, politisch deutlich näherstehend als Smend, der, ebenso wie Triepel, schon 1930 zur Apologie des Präsidialsystems auf Abstand gegangen war und mit dem Schmitt seitdem in alter Verbundenheit mehr diplomatische Beziehungen unterhielt. Mit Bilfinger pflegte Schmitt seit 1924 freundschaftliche und auch familiäre Beziehungen. Schon vor ihrer engen Zusammenarbeit als Prozessvertreter in der Rechtssache Preußen contra Reich vor dem Leipziger Staatsgerichtshof übernachteten beide in Halle und Berlin häufig wechselseitig im Hause. Da Bilfinger mit Bruns verwandt und befreundet war, erstreckte sich der Umgang vor 1933 auch auf Bruns. Man begegnete sich bei diversen Gelegenheiten und unternahm auch kleinere Touren zusammen in Bruns Horch-Limousine in die Umgebung. Auch wenn nur wenige Briefe von Bruns im Nachlass Schmitts erhalten sind, belegen die erhaltenen Tagebücher doch eindeutig, dass beide sich näher kannten. Bruns war kein NSDAP-Mitglied und dachte politisch wohl deutlich gemäßigter als sein Vetter Bilfinger. Schmitts Tagebuch verzeichnet gerade für die Jahre 1933/34 zahlreiche Begegnungen und positive Erwähnungen in fachlichen Zusammenhängen, an die sich private Geselligkeit anschloss. So hörte Bruns am 24. Januar 1934 Schmitts Vortrag über „Heerwesen und staatliche Gesamtstruktur“, die Exposition der verfassungsgeschichtlichen Programmschrift „Staatsgefüge und Zusammenbruch des zweiten Reiches“; Schmitt hörte am 4. Juli 1934 im Gegenzug Bruns‘ Vortrag über „Völkerrecht und Politik“.[13]

Mit Bilfinger stand Schmitt nach 1933 weiter in enger Beziehung. Dieser optierte nicht weniger entschlossen als Schmitt für den Nationalsozialismus. Auch wenn sich ab etwa 1934 eine gewisse Ermüdung in der Beziehung beobachten oder vermuten lässt, blieb sie doch nach 1933 – und auch nach 1945 noch – relativ eng und freundschaftlich. So übernahm Bilfinger Schmitts alten Bonner Schüler Karl Lohmann als Mitarbeiter und ermöglichte ihm in Heidelberg die Habilitation. Für die Entwicklung der Beziehung zu Bruns nach 1934 fehlen aussagekräftige Quellen. Zwar ist nicht von engen freundschaftlichen Kontakten auszugehen, doch gibt es keine Anzeichen für ein Zerwürfnis. So verwundern die negativen Äußerungen von 1941 wie 1947; Loyalität war aber gewiss nicht Schmitts Stärke.

Das KWI aus Schmitts Sicht

In seiner Stellungnahme gegenüber Kempner 1947 geht Schmitt auch auf die Arbeit des KWI im Dritten Reich, insbesondere auf die ZaöRV ein, deren Mitherausgeber er war. In seinen weiteren Ausführungen ging er seine Zeitschriftenbeiträge einzeln durch und betonte jeweils die „wissenschaftliche“ Zielführung und Selbständigkeit seiner Äußerungen. Zum KWI meinte er hier:

„Die bedeutendste rechtswissenschaftliche Zeitschrift, die in diesen Jahren (1939-1945) völkerrechtliche Fragen vom deutschen Standpunkt aus behandelte, war die ‚Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht‘, herausgegeben von Prof. Viktor Bruns, dem Direktor des ‚Instituts für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht‘ der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft. Bruns, der auch den Völkerrechts-Ausschuss der Akademie für Deutsches Recht leitete, war ein Völkerrechtler von internationalem Ansehen und grosser persönlicher Vornehmheit. Als er im Herbst 1943 starb, hat ihm das ‚American Journal of International Law‘ einen respektvollen Nachruf gewidmet. Einer der Mitherausgeber der Zeitschrift war Graf Stauffenberg, ein Bruder, Mitarbeiter und Schicksalsgenosse des Grafen Stauffenberg, der das Attentat auf Hitler am 20. Juli 1944 unternommen hat. Mein Name stand neben dem Namen von Heinrich Triepel auf der Zeitschrift als „unter Mitwirkung von“ Triepel und mir herausgegeben. Ich habe jedoch seit 1936 keinen Einfluss mehr auf die Zeitschrift genommen und auch keinen Aufsatz mehr veröffentlicht. Die Zeitschrift hat im übrigen wertvolle Aufsätze gebracht und gutes Material veröffentlicht, das sie von amtlichen deutschen Stellen erhielt. Wie sich ihre Zusammenarbeit mit dem Auswärtigen Amt und anderen Behörden abspielte, weiss ich nicht. Ich habe mich nicht darum gekümmert und Prof. Bruns hätte mich in dieses, von ihm streng gehütete Arcanum seiner Zeitschrift wohl auch keinen Einblick tun lassen.“[14]

Die Ausführungen sind voller Ambivalenzen. Einerseits lobt Schmitt und andererseits setzt er doch leise herab. So zitiert er den Stauffenberg-Mythos herbei und betont andererseits doch die „advokatorische“ Rolle des Instituts. In der Zeitschrift des Instituts publizierte er damals immerhin eine Selbstanzeige[15] seiner Besprechungsabhandlung „Die Wendung zum diskriminierenden Kriegsbegriff“. Dass er keinen großen Aufsatz veröffentlichte, sondern andere NS-Organe präferierte, widerspricht eigentlich dem Zweck seiner Ausführungen. In seiner Stellungnahme von 1947 nennt Schmitt diverse Akteure, Wirkungskreise und Konkurrenzen.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://mpil100.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Picture1.pdf”]Das Titelblatt der ZaöRV-Ausgaben Bd. III (1933) bis V (1934). Carl Schmitt erscheint als Mitherausgeber, Rudolf Smend und Erich Kaufmann wurden entfernt.

Wo Schmitt genau in den diversen Fragen zwischen Göring, Frank und Joseph Goebbels, Otto Koellreutter, Reinhard Höhn und Werner Best, Triepel, Bruns und Bilfinger stand, ist bei dem wendigen und enigmatischen Autoren schwer zu sagen. Gerade im Völkerrecht suchte er als Anwalt der „legalen Revolution“ und „Bewegung“ institutionelle Alternativen zum Staat des 19. Jahrhunderts. Schon in der Auseinandersetzung mit Triepel kritisierte er die „dualistische Theorie“ strikter Unterscheidung von Völkerrecht und Landesrecht mit ihrer völkerrechtlichen Orientierung am Staatsbegriff. „Völkerrechtliche Großraumordnung“ propagierte dann den „Reichsbegriff“ als Grundbegriff eines hegemonialistischen Völkerrechtsdenkens, das Macht und Recht eng miteinander verknüpfte und Macht ins Recht setzte, wenn und sobald sie als „konkretes Ordnungsdenken“ politische Souveränität und Ordnung formierte.

Schmitts Suche nach institutionellen Alternativen zum „bürgerlichen Rechtsstaat“ und einer neuen Verfassung – nach dem Oxymoron eines nationalsozialistischen „Normalzustands“ – implizierte auch Alternativen zum überlieferten Wissenschaftssystem und Juristentypus.[16] Schmitt bejahte Franks Gründung einer Akademie für Deutsches Recht als eine solche institutionelle Alternative. Auch als Autor und Herausgeber suchte er neue publizistische Formen akademischer Auseinandersetzung. So begründete er die Reihe Der deutsche Staat der Gegenwart, in der programmatische Kampfschriften zur Gleichschaltung und Neuausrichtung der Rechtswissenschaft erschienen. Zweifellos betrachtete er das KWI und dessen Zeitschrift nicht als Musterfall und Inbegriff einer nationalsozialistischen Institution. Ob er deren Form und Wirksamkeit strategisch mit Blick auf die internationale Außenwirkung schätzte, ist schwer zu sagen. Als ein Nachfolger von Bruns hätte er manches gewiss verändert. In sein Tagebuch notierte er am 25. Oktober 1943 Ärger über Bilfingers Ernennung zum Direktor des Instituts: „Bilfinger soll Nachfolger von Bruns werden. Schadenfroh darüber, welch lächerliche Vetternwirtschaft, Schieberei über den Tod hinaus.“[17] Als Bilfinger 1949 dann überraschend erneut Direktor des Instituts wurde,[18] brach er den über 25 Jahre doch recht intensiven Kontakt brüsk ab. Hatte er 1943, nach dem Tod von Bruns, wirklich erwartet, Institutsdirektor zu werden? Eine realistische Aussicht war das wohl nicht. Wie Professoren aber so sind, wollte er damals vielleicht wenigstens gefragt werden. Eigentlich passte das Amt, wie er wohl wusste, aber nicht zu seiner Person und Rolle. Er gehörte eher zu den nationalsozialistischen Scharfmachern und verstand sich weniger auf überzeugende Diplomatie. Auch deshalb war er bald isoliert.

***

Andere Fassung des Blog-Beitrags in: Reinhard Mehring, “Dass die Luft die Erde frisst…” Neue Studien zu Carl Schmitt, Baden-Baden 2024, S. 91-107.

Zudem sei verwiesen auf die im Frühjahr erscheinende Edition zum Briefwechsel zwischen Carl Schmitt und Carl Bilfinger: Philipp Glahé / Reinhard Mehring / Rolf Rieß (Hrsg.), Der Staats- und Völkerrechtler Carl Bilfinger (1879-1958). Dokumentation seiner politischen Biographie. Korrespondenz mit Carl Schmitt, Texte und Kontroversen, Baden-Baden 2024.

[1] Vor allem: Carl Schmitt, Das Reichsstatthaltergesetz, Berlin: Carl Heymanns Verlag 1934.

[2] Wolfgang Schuller (Hrsg.), Carl Schmitt Tagebücher 1930 bis 1934, Berlin: Akademie Verlag 2010, 303.

[3] Viktor Bruns, Deutschlands Gleichberechtigung als Rechtsproblem, Berlin: Carl Heymanns Verlag 1933.

[4] Carl Schmitt, Nationalsozialismus und Völkerrecht, in: Günter Maschke (Hrsg.), Carl Schmitt Frieden oder Pazifismus? Arbeiten zum Völkerrecht und zur internationalen Politik 1924-1978, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2005, 391-423, 393.

[5] Carl Schmitt, Der Neubau des Staats- und Verwaltungsrechts, in: Carl Schmitt, Gesammelte Schriften 1933-1936, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2021, 57-69.

[6] Carl Schmitt, Staat, Bewegung, Volk. Die Dreigliederung der politischen Einheit, in: Schmitt (Fn. 6), 76- 115, 105-106.

[7] Dazu: Carl Schmitt, Führung und Hegemonie, in: Günter Maschke (Hrsg.): Carl Schmitt Staat, Großraum, Nomos. Arbeiten aus den Jahren 1916-1969, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 1995, 225-231.

[8] Carl Schmitt, Stellungnahme I: Untermauerung der Hitlerschen Großraumpolitik; Stellungnahme II: Teilnehmer des Delikts „Angriffskrieg“? in: Helmut Quaritsch (Hrsg.), Carl Schmitt Antworten in Nürnberg, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2000, 68-90.

[9] 1936 war Schmitt gescheitert mit: Carl Schmitt, Stellungnahme der Wissenschaftlichen Abteilung des National-Sozialistischen Rechtswahrerbundes zu dem von der amtlichen Strafprozesskommission des Reichsjustizministeriums aufgestellten Entwurf einer Strafverfahrensordnung, in: Schmitt (Fn. 6), 431-481.

[10] So hielt er am 30. März 1935 ein Referat über das „Problem der gegenseitigen Hilfeleistung der Staaten“ in der 3. Vollsitzung des Ausschusses für Völkerrecht. Am 6. Mai 1938 stellte er in der 2. Sitzung der Völkerrechtlichen Gruppe seinen Bericht über „Die Wendung zum diskriminierenden Kriegsbegriff“ vor. Die Protokolle der Akademie verzeichnen noch die Teilnahme und einen Redebeitrag zu Vorträgen von Arnold Toynbee (28. Februar 1936 und Sommer 1937).

[11] Reinhard Mehring (Hrsg.), „Auf der gefahrenvollen Straße des öffentlichen Rechts“ Briefwechsel Carl Schmitt – Rudolf Smend 1921-1961, 2. überarb. Aufl., Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2012, 103f.

[12] Werner Schubert (Hrsg.), Akademie für Deutsches Recht. Ausschüsse für Völkerrecht und für Nationalitätenrecht (1934-1943), Frankfurt: Peter Lang Verlag 2002, 164.

[13] Schmitt (Fn. 5), 392; dazu: Schuller (Fn.3), 349; vgl. dazu: Viktor Bruns, Völkerrecht und Politik, Berlin: Junker und Dünnhaupt 1934.

[14] Schmitt (Fn. 9), 73f.

[15] Carl Schmitt, Die Wendung zum diskriminierenden Kriegsbegriff (Selbstanzeige), ZaöRV 8 (1938), 588-590.

[16] Dazu etwa: Carl Schmitt, Bericht über die Fachgruppe Hochschullehrer im BNSDJ, in: Schmitt (Fn. 6), 116-118; Carl Schmitt, Aufgabe und Notwendigkeit des deutschen Rechtsstandes, in: Schmitt (Fn. 6), 350-361; Carl Schmitt, Geleitwort: Der Weg des deutschen Juristen, in: Schmitt (Fn. 6), 165-173.

[17] Diese Information danke ich Dr. Gerd Giesler.

[18] Dazu eingehend: Felix Lange, Carl Bilfingers Entnazifizierung und die Entscheidung für Heidelberg. Die Gründungsgeschichte des völkerrechtlichen Max-Planck-Instituts nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, ZaöRV 74 (2014), 697-731.

|

Suggested Citation: Reinhard Mehring, Polykratie der Völkerrechtler. Carl Schmitt, Viktor Bruns und das KWI für Völkerrecht, MPIL100.de, DOI: 10.17176/20240327-103002-0 |

|

| Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED | |

English

Carl Schmitt, Viktor Bruns and the KWI for International Law

On 2 November 1933, the Chairman of the Board of Trustees wrote “to the members of the Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law”:

“The Director of the Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, Privy Councillor of Justice Professor Dr Bruns, has requested that the State Councillor Professor Dr Carl Schmitt, who has been appointed ordinary professor at the Faculty of Law of the University of Berlin, be elected scientific advisor to the Institute. The Director of the Institute has added the following in support of his application:

‘The position that Professor Dr Carl Schmitt occupies in the science of his subject makes a justification of this motion superfluous. I would merely like to point out the great importance for the work of the institute corresponding to the appointment of this scholar, who is involved to an outstanding degree in the preparation of new laws[1] . It is to be expected that through his person, the work of the institute in the field of constitutional law will be placed in the direct service of practical government responsibilities. This corresponds to the goals and tasks which the institute has set itself since its founding and which it has since been called upon to realise especially in the field of international law.’

I put this motion to the vote in accordance with § 5 of the Institute’s Statutes.

If I am not honoured with a reply by the 15th of this month, I assume that the members of the Board of Trustees are in agreement with the proposal.”

Carl Schmitt had declared his acceptance of the call to Berlin on 8 September and had a “very friendly”[2] meeting with Viktor Bruns in a hotel room a few days later, on 18 September. Perhaps they discussed his employment as an “advisor” at the Institute on that occasion. On 5 November, i.e. a few days after the letter from the Chairman of the Board of Trustees, Schmitt notes a meeting with Bruns and Richard Bilfinger “at the Fürstenhof ” after a “meeting of the Academy for German Law [Akademie für Deutsches Recht]”. At that meeting, Bruns gave a lecture on “Germany’s equality as a legal problem.[3] In his treatise on international law “Nationalsozialismus und Völkerrecht” (“National Socialism and International Law”), Schmitt wrote about the lecture: “Our claim to equal rights has only recently been set out by Viktor Bruns in an almost classical manner towards his various legal functions.”[4] Only very rarely did he cite publications by Bruns. The positive mention of balanced legal analysis is also somewhat poisoned; in other contexts, Schmitt might have spoken more disparagingly of liberal, diplomatically restrained positivism. In any case, at the end of 1933, when Schmitt is just arriving in Berlin in his new role as “crown jurist”, his contact with Bruns seems particularly intense and positive. If we return here to the letter from the Chairman of the Board of Trustees, it is almost surprising that in November 1933 elections were still held in accordance with the statutes, since the university constitution had just been changed to fit the “Führer principle”. The election is also questionable from a formal point of view, since objections are only accepted up to a deadline, for a motion that declares its justification “superfluous” and naturally assumes approval. Were all members of the Institute eligible to vote or only the trustees, as is implied? Was a vote taken? What were Bruns intentions behind replacing Erich Kaufmann with Schmitt? Did he expect an intensification of legal-political influence in the “constitutional law field”? Was it a gesture of loyalty or did he also seek to secure the institute through the “Councillor of State” and protect it from encroachment?

The “crown lawyer” at KWI. A strategic choice?

Only few sources on Schmitt’s advisory function can be found in the MPI archives. Schmitt had transitioned from Cologne to Berlin University in autumn 1933 with a decidedly “state-political (staatspolitisch)” mandate and was at the zenith of his Nazi career. He had been appointed Prussian State Councillor by Hermann Göring and had been cooperating closely with the “Reich Commissar (Reichskommissar)” and “Reich Law Leader (Reichsrechtsführer)” Hans Frank for several months. At the German Lawyers’ Congress (Deutscher Juristentag), actually the 4th Conference of the Federation of National Socialist German Lawyers (Bund Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher Juristen, BNSDJ), which was opened by Adolf Hitler himself, he had just, on 3 October, given a programmatic speech on the “Reconstruction of Constitutional- and Administrative Law“[5], which emphasised “Führertum and ethnic identity [Artgleichheit] as fundamental concepts of National Socialist law” and recommended the institution of the new State Council as the “first illustrative and exemplary figure” for the “establishment of a Führer Council”, to which the ambition of the “crown jurist” probably aspired at the time. [6]

Schmitt relied on a thorough transformation of the “total state” into a personalistically integrated, more or less “charismatic” “Führer state”. It is in line with this thinking when Bruns writes in his slightly oblique octroy that through his “person, the work of the institute in the field of constitutional law will be placed in the direct service of practical government responsibilities”. In Bruns’ careful wording, a distinction between the scientific institute and political practitioners, who act independently and are only employed as “advisors” is alluded to. What Schmitt actually did for his pay has not yet been researched and is in part probably not even fixated in writing. However, his institutional involvement remained relatively weak in the following years. Although he had driven Erich Kaufmann, with whom he had been cordial enemies since their days together in Bonn, out of the university by intense anti-Semitic denunciation and had taken over his role at the KWI and he also became co-editor of the institute’s Journal Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (ZaöRV; today: Heidelberg Journal of International Law, HJIL), he most-likely never belonged to Bruns’ closest and innermost circle of advisors and contributors. During the next few years, he occasionally worked in the institute’s library, which was splendidly housed in the city palace next to the university, and probably also sought occasional discussions there, especially with Heinrich Triepel, on whose concept of hegemony Schmitt took a critical position in an in-depth review;[7] however, the KWI probably never became the preferred stage for his National Socialist Gleichschaltung activities.

As extensive and intensive as international research on Schmitt is, it lacks sources for a precise description of Schmitt’s multifaceted legal-political work, especially for the period after 30 June 1934. The self-description during his pretrial detention in Nuremberg in 1947 must therefore suffice as a basic access point here, even if it is obviously apologetically embellished.[8] Prosecutor Robert Kempner wanted a written statement on the question of whether Schmitt had “promoted the theoretical underpinning of Hitler’s Großraum policy”. Schmitt denied this at length. On that occasion he also mentioned his role at the KWI and his relationship with Viktor Bruns:

“Since 1936, I have not been asked by anyone, neither by an office nor by a person, neither officially nor privately, for an expert opinion[9] and I have not given such an opinion, neither for the Foreign Office nor for a party [NSDAP] office nor for the Wehrmacht, the economy or the industrial sector. Nor have I given any advice that was in any way even remotely connected with Hitler’s policy of conquest or occupation. […] Like many other law professors, I took part in several meetings of the Committee for International Law of the Academy for German Law, which was chaired by Prof. Bruns,[10] but I kept completely to myself there, even in discussions, and did not have or seek the slightest influence. […] I did not take on any office or position during the war, neither as a court martial councillor, nor as a war administrative councillor in occupied territory, nor as a member of an admiralty court or anything similar. Neither was I offered any such position, nor did I seek it. I did not even succeed Prof. Bruns as director of the Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (Kaiser Wilhelm Society) when Prof. Bruns died in September 1943. […] I did not have an institute, never became rector or dean.”

In view of the numerous misrepresentations he makes strategically, the almost astonished formulation that he “did not even” succeed Bruns is astonishing. Was the office so insignificant? Could Schmitt still make claims at the end of 1943 if he had really been as powerless “since 1936” as he would have us believe?

Schmitt and his relationship to Viktor Bruns and Carl Bilfinger

In May 1941, Schmitt commented to Rudolf Smend about one of the meetings of the International Law Committee; he called this “rout” one of the “humiliations of pure science” and elaborated:

“To see how professors feel highly honoured when they are allowed to listen to younger speakers or even old ones from the ministry is very sad. When then a ‘discussion’ led by Bruns occurs, in which Mr Thoma, Mr Bilfinger Mr von Düngern [sic!], who is just as old, present pioneering concepts – with expressions of gratitude that they have been granted such distinguishing permission – to the address of his high authorities, one longs for the garret.” [11]

That Schmitt made such disparaging remarks about Richard Thoma, Bruns and Bilfinger in 1941 is somewhat surprising. Schmitt refers to a meeting on 2 May 1941 on the agenda item “Land War Convention [Landkriegsordnung]”. Conrad Roediger spoke about the “codified law of the land [Landrecht] in the present war”. Richard Thoma spoke in a longer statement about the “validity of international law in the General Government”, i.e. in Hans Frank’s sphere of power. Thoma asked how one could “achieve a conformity of the German government’s actions in this completely overcome area with international law”.[12] He argued that occupatio bellica could not be used as legal grounds, but instead an open declaration that the “occupation is carried out with the intentio of the complete destruction of the defeated enemy”. Thoma thus dunned international law and an open declaration of National Socialist extremism. Otto von Dungern immediately objected in National Socialist spirit, Bruns as chairman then promptly ended the discussion. A statement by Schmitt, who authored „Die Wendung zum diskriminierenden Kriegsbegriff“ (“The Turn to the Discriminating Concept of War”), is not recorded. His letter to Smend thus belittles Thoma by associating him with von Dungern, although, or precisely because, Thoma took the contrary position and called to mind international law in the General Government. Schmitt’s polemics make one doubt that he represented a “classical” concept of war. He considered open mentioning of the war crimes in Frank’s General Government taboo. The fact that he polemicized against Thoma in letters to Smend is not surprising given his political differences with Smend. More surprising are the negative remarks about Bilfinger and Bruns.

Previously, he had maintained comparatively friendly relations with all three. Bilfinger must even be described as one of his closest companions; clearly closer to Schmitt in political terms than Smend, who, like Triepel, had already distanced himself from the apologia of the presidential system in 1930 and with whom Schmitt had since maintained rather diplomatic relations based on old ties. Schmitt had however maintained friendly and also familiar relations with Bilfinger since 1924. Even before their close collaboration as councils in the Prussia versus Reich case before the Leipzig State Court, the two frequently stayed overnight in each other’s homes in Halle and Berlin. Since Bilfinger was a relative and friend of Bruns, their interactions before 1933 also extended to Bruns. They met on various occasions and also went on short trips together in Bruns’ Horch limousine to the surrounding area. Even though only a few letters from Bruns have been preserved in Schmitt’s estate, the surviving diaries clearly prove that the two knew each other quite well. Bruns was not a member of the NSDAP and was probably much more politically moderate than his cousin Bilfinger. Schmitt’s diary records numerous meetings and positive mentions in professional contexts, followed by private socialising, especially for the years 1933/34. On 24 January 1934, for example, Bruns heard Schmitt’s lecture on the “army and the overall structure of the state”, the exposition of the constitutional-historical treatise “Staatsgefüge und Zusammenbruch des zweiten Reiches” (“State-composition and collapse of the Second Reich [German Empire]”); in return, Schmitt heard Bruns’ lecture on “international law and politics” on 4 July 1934.[13]

Schmitt remained in close contact with Bilfinger after 1933. The latter opted for National Socialism no less resolutely than Schmitt. Even if a certain cooling of the relationship can be observed or assumed from around 1934, it remained relatively close and friendly after 1933 – and even after 1945. Bilfinger took on Schmitt’s former student from Bonn Karl Lohmann as an employee and enabled him to complete his habilitation treatise in Heidelberg. There are no meaningful sources for the development of his relationship with Bruns after 1934. Although close friendly contacts cannot be assumed, there are no signs of a rift. The negative statements of 1941 and 1947 are therefore surprising; loyalty was however certainly not Schmitt’s strong suit.

The KWI from Schmitt’s point of view

In his statement to Kempner in 1947, Schmitt also addresses the work of the KWI in the Third Reich, in particular the ZaöRV, of which he was co-editor. In his further remarks, he went through his journal contributions one by one, emphasising in each case the “scientific” aim and independence of his statements. Regarding the KWI, he said here:

“The most important jurisprudential journal that dealt with questions of international law from the German point of view during these years (1939-1945) was the ‘Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht’, edited by Prof. Viktor Bruns, the director of the ‘Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law’ of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. Bruns, who also headed the International Law Committee of the Academy of German Law, was an international law scholar of international renown and great personal distinction. When he died in autumn 1943, the ‘American Journal of International Law’ dedicated a respectful obituary to him. One of the co-editors of the journal was Graf Stauffenberg, a brother, associate and companion in fate of the Graf Stauffenberg, who made the assassination attempt on Hitler on 20 July 1944. My name was next to Heinrich Triepel’s on the journal as “published with the cooperation of” Triepel and myself. However, I have had no influence on the journal since 1936 and have not published any essays. Incidentally, the journal produced valuable essays and published good material that it received from official German agencies. How its cooperation with the Foreign Office and other authorities played out, I do not know. I did not bother and Prof. Bruns would probably not have let me gain insightinto this arcanum of his journal, which he guarded closely. [14]

The remarks are full of ambivalences. On the one hand, Schmitt praises and yet on the other hand he quietly disparages. Thus, he cites the Stauffenberg mythos and yet on the other hand emphasises the “advocatory” role of the Institute. It remains that he did publish a self-disclosure[15] of his review essay “Die Wendung zum discriminierenden Kriegsbegriff” (“The Turn to the Discriminating Concept of War”), in the institute’s journal at the time. The fact that he did not publish a major essay, but preferred other Nazi organs, actually contradicts the purpose of his remarks. In his 1947 statement, Schmitt names various actors, spheres of activity and competitors.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://mpil100.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Picture1.pdf”]The title page of the ZaöRV editions Vol. III (1933) to V (1934). Carl Schmitt appears as co-editor, Rudolf Smend and Erich Kaufmann have been removed.

Where exactly Schmitt stood between Göring, Frank and Joseph Goebbels, Otto Koellreutter, Reinhard Höhn and Werner Best, Triepel, Bruns and Bilfinger on various issues is difficult to say with the agile and enigmatic author. Particularly in international law, he sought institutional alternatives to the state of the 19th century as an advocate of the “legal revolution” and “movement”. In debate with Triepel, he had already criticised the “dualistic theory” of strict distinction between international law and national law with its orientation on the concept of the state stemming from international law. His work “Völkerrechtliche Großraumordnung” (“The Großraum Order of International Law”) then propagated the “concept of empire” as the central concept of hegemonialist thinking on international law, which closely linked power and law and equated power to law if and when it formed political sovereignty and order as “konkretes Ordnungsdenken” (roughly: theory of factual order).

Schmitt’s search for institutional alternatives to the “civic constitutional state” and a new constitution – after the oxymoron of a National Socialist “Normalzustand” (“normal state”, as opposed to the state of exception) – also implied alternatives to the traditional academic system and type of jurist.[16] Schmitt affirmed Frank’s founding of an Academy for German Law as such an institutional alternative. As an author and editor, he also sought new journalistic forms of academic debate. Thus, he founded the series “Der deutsche Staat der Gegenwart” (“The German State of the Present”), in which programmatic pamphlets on the Gleichschaltung and reorientation of jurisprudence were published. There is no doubt that he did not regard the KWI and its journal as a model and epitome of a National Socialist institution. It is difficult to say whether he appreciated its form and effectiveness from a strategic point of view due to its international impact. As a successor to Bruns, he would have certainly made some changes. On 25 October 1943, he noted his annoyance at Bilfinger’s appointment as director of the institute in his diary: “Bilfinger is to be Bruns’ successor. Gloating about it, what ridiculous nepotism, racketeering even beyond death.”[17] When Bilfinger surprisingly became director of the Institute again in 1949,[18] he brusquely broke off the contact, which had been quite intensive for 25 years. Did he really expect to become director of the Institute in 1943, after Bruns’ death? That was probably not a realistic prospect. But perhaps, in typical professorial fashion, he at least wanted to be asked. Yet, as he well knew, the office did not fit his person and role. He was more of a National Socialist agitator and less adept at convincing diplomacy. This was one of the reasons he was soon isolated.

Translation from the German original: Sarah Gebel

[1] Above all: Carl Schmitt, Das Reichsstatthaltergesetz, Berlin: Carl Heymanns Verlag 1934.

[2] Wolfgang Schuller (ed.), Carl Schmitt Tagebücher 1930 bis 1934, Berlin: Akademie Verlag 2010, 303.

[3] Viktor Bruns, Deutschlands Gleichberechtigung als Rechtsproblem, Berlin: Carl Heymanns Verlag 1933.

[4] Carl Schmitt, Nationalsozialismus und Völkerrecht, in: Günter Maschke (ed.), Carl Schmitt Frieden oder Pazifismus? Arbeiten zum Völkerrecht und zur internationalen Politik 1924-1978, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2005, 391-423, 393.

[5] Carl Schmitt, Der Neubau des Staats- und Verwaltungsrechts, in: Carl Schmitt, Gesammelte Schriften 1933-1936, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2021, 57-69.

[6] Carl Schmitt, Staat, Bewegung, Volk. Die Dreigliederung der politischen Einheit, in: Schmitt (fn. 6), 76- 115, 105-106.

[7] On this: Carl Schmitt, Führung und Hegemonie, in: Günter Maschke (ed.): Carl Schmitt Staat, Großraum, Nomos. Arbeiten aus den Jahren 1916-1969, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 1995, 225-231.

[8] Carl Schmitt, Stellungnahme I: Untermauerung der Hitlerschen Großraumpolitik; Stellungnahme II: Teilnehmer des Delikts „Angriffskrieg“? in: Helmut Quaritsch (ed.), Carl Schmitt Antworten in Nürnberg, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2000, 68-90.

[9] In 1936, Schmitt had failed with: Carl Schmitt, Stellungnahme der Wissenschaftlichen Abteilung des National-Sozialistischen Rechtswahrerbundes zu dem von der amtlichen Strafprozesskommission des Reichsjustizministeriums aufgestellten Entwurf einer Strafverfahrensordnung (Statement of the Scientific Department of the National Socialist Federation of Lawkeepers [National-Sozialistischer Rechtswahrerbund] on the Draft of a Law of Criminal Proceedings as Presented by the Official Commission on Criminal Proceedings of the Reich Ministry of Justice), in: Schmitt (Fn. 6), 431-481.

[10] Thus, on 30 March 1935, he gave a presentation on the “Problem of Mutual Assistance Between States” at the 3rd plenary session of the Committee on International Law. On 6 May 1938, he presented his report on “The Turn to the Discriminating Concept of War” at the 2nd session of the International Law Group. The Academy minutes also record the participation in and a verbal contribution to presentations by Arnold Toynbee (28 February 1936 and summer 1937).

[11] Reinhard Mehring (ed.), “Auf der Gefahrenvollen Straße des öffentlichen Rechts” Briefwechsel Carl Schmitt – Rudolf Smend 1921-1961, 2nd revised edition, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2012, 103f.

[12] Werner Schubert (ed.), Academy for German Law. Committees for International Law and for Nationality Law (1934-1943), Frankfurt: Peter Lang Verlag 2002, 164.

[13] Schmitt (fn. 5), 392; see on this Schuller (fn. 3), 349; cf: Viktor Bruns, Völkerrecht und Politik, Berlin: Junker und Dünnhaupt 1934.

[14] Schmitt (fn. 9), 73f.

[15] Carl Schmitt, Die Wendung zum diskriminierenden Kriegsbegriff (Selbstanzeige), HJIL 8 (1938), 588-590.

[16] On this, for example: Carl Schmitt, Bericht über die Fachgruppe Hochschullehrer im BNSDJ, in: Schmitt (fn. 6), 116-118; Carl Schmitt, Aufgabe und Notwendigkeit des deutschen Rechtsstandes, in: Schmitt (fn. 6), 350-361; Carl Schmitt, Geleitwort: Der Weg des deutschen Juristen, in: Schmitt (fn. 6), 165-173.

[17] I would like to thank Dr Gerd Giesler for this information.

[18] In detail: Felix Lange, Carl Bilfingers Entnazifizierung und die Entscheidung für Heidelberg. Die Gründungsgeschichte des völkerrechtlichen Max-Planck-Instituts nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, HJIL 74 (2014), 697-731.

|

Suggested Citation: Reinhard Mehring, Polycratic International Law Scholarship. Carl Schmitt, Viktor Bruns and the KWI for International Law, MPIL100.de, DOI: 10.17176/20240327-103053-0 |

|

| Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED | |

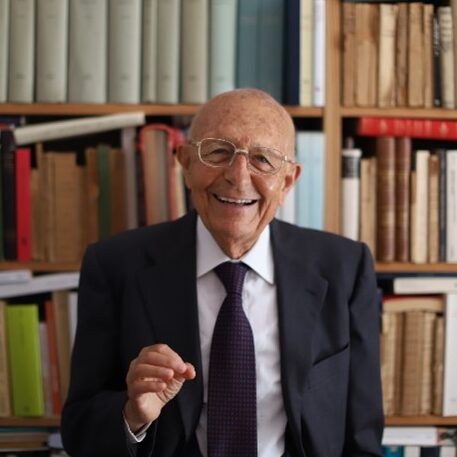

Reinhard Mehring ist seit 2007 Professor für Politikwissenschaft und ihre Didaktik an der Pädagogischen Hochschule Heidelberg. Zuletzt von ihm erschienen: Reinhard Mehring, “Dass die Luft die Erde frisst…” Neue Studien zu Carl Schmitt, Baden-Baden 2024 .