„Unsere Strassen stürmen die Autos […]. Im Luftraum gleiten Flugzeuge […]; sie missachten die Landesgrenzen und verringern den Abstand von Volk zu Volk. […] Die Gleichzeitigkeit der Ereignisse erweitert maßlos unsern Begriff von „Zeit und Raum“, sie bereichert unser Leben. […] Wir werden Weltbürger. […] Gewerkschaft, Genossenschaft, A. G., G. m. b. H., Kartell, Trust und Völkerbund sind die Ausdrucksformen heutiger gesellschaftlicher Ballungen […]. Kooperation beherrscht alle Welt. […] Jedes Zeitalter verlangt seine eigene Form. […] Internationalität ist ein Vorzug unsrer Epoche.“[1]

Dieses Zitat stammt nicht aus der Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (ZaöRV), sondern aus dem 1926 veröffentlichten Aufsatz „Die Neue Welt“ des Architekten und Urbanisten Hannes Meyer. Meyer war von 1926 bis 1930 am Bauhaus tätig, zuletzt als Direktor. 2023/24 erleben wir nicht nur 100 Jahre Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, sondern auch 100 Jahre Bauhausausstellung Weimar. Im Bauhaus war die Ausrichtung zwischen Wissenschaft und Praxis ein Grundsatzkonflikt. Das 1924 gegründete Kaiser‑Wilhelm‑Institut (KWI) für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht sollte sich mit den Rechtsfragen seines Zuständigkeitsbereichs aus einer praxisorientierten und dogmatischen Perspektive zu befassen. Diese Ausrichtung ist entscheidend für das Verständnis der Weimarer Jahre des Instituts unter dem Direktorat Viktor Bruns’. Zum einen sollte damit das Völkerrecht als Rechtssystem gefördert und der Standard der Völkerrechtswissenschaft in Deutschland gehoben werden. Zum anderen aber wurde die am KWI versammelte Rechtsexpertise als wichtiger Faktor für die Positionierung Deutschlands gegenüber dem Versailler Vertrag angesehen.[2] Insofern also bewegte sich auch das KWI zwischen Wissenschaft und Praxis oder „zwischen Wissenschaft und Politikberatung“.[3]

Abgesehen von diesen Parallelen ist Meyers Text aus einem weiteren Grund für das Verständnis des KWI der Weimarer Jahre von Interesse: Der Text zeugt von einer gefühlten Internationalität in der Mitte der 1920er Jahre, die zwar nicht repräsentativ gewesen sein wird, aber dennoch prägend. Die Internationalität in Kunst und Kultur, aber auch der Wirtschaft war schon vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg sehr weit fortgeschritten; der Krieg zerstörte viele dieser Verbindungen.[4] Internationalität war jedoch für die Einzelnen auch im Alltag der Weimarer Jahre vielfältig wahrnehmbar und erfahrbar. Die Agenda des KWI blieb dagegen im Wesentlichen auf die Außenbeziehungen im klassisch zwischenstaatlichen Sinn ausgerichtet. Das entsprach der auch von den Zeitgenossen „scharf“ gezogenen „Grenze“ zwischen Völkerrecht und Staatsrecht.[5] Dabei sollte sich das Institut nicht allein mit dem Völkerrecht befassen, denn die mögliche Anwendung des Völkerrechts in der Praxis hing weitgehend von den verfassungsrechtlichen Zwängen der Staaten ab. Deshalb erschien es notwendig, auch das ausländische öffentliche Recht in die Forschung einzubeziehen.[6] Dementsprechend sind „ausländisches öffentliches Recht“ und „Völkerrecht“ Namensbestandteile nicht nur des KWI, sondern auch der 1927 begründeten Beiträge zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht und der seit 1929 erscheinenden ZaöRV.

Nicht im Fokus stand konsequenterweise das inländische Außenverfassungsrecht der auch insoweit innovativen Weimarer Reichsverfassung (WRV) von 1919. Das „Außenverfassungsrecht“ war in den 1920er Jahren noch nicht als Forschungsfeld etabliert. Als Lehrfach („Staatsrecht III“) und Gegenstand von Veröffentlichungen entstand das Außenverfassungsrecht erst sehr viel später, in der Bundesrepublik Mitte der 1970er Jahre.[7] Jedoch hatte sich der Rechtsbegriff der „auswärtigen Gewalt“ bereits mit dem 1892 veröffentlichten Lehrbuch von Albert Hänel durchgesetzt[8] und es war den Zeitgenossen bewusst, dass die Frage nach dem Verhältnis von Völkerrecht und innerstaatlichem Recht angesichts sich vervielfachender internationaler Berührungspunkte ständig an Bedeutung gewann.[9] Offensichtlich wurde 1924 kein Institut für „Völkerrecht und Landesrecht“ gegründet. Dennoch ist die Beobachtung nicht trivial: Mit der Ausrichtung des Instituts ging auch eine Perspektive auf das „Völkerrecht“ selbst „als Rechtsordnung“[10] verloren. Sie betrifft seine – potentielle – Bedeutung für die Einzelnen, seine Auswirkungen auf die innerstaatliche Rechts- und Sozialordnung unter der neuen Verfassung sowie seinen Zusammenhang mit dem demokratischen Prozess und seine Bedeutung für die gerichtliche Praxis. Es entstand eine programmatische Lücke zwischen „ausländischem öffentlichen Recht“ und „Völkerrecht“. Zugleich wurde der Blick auf die Bedeutung des Völkerrechts jenseits der klassischen Außenbeziehungen verstellt.

Innovatives Weimarer „Außenverfassungsrecht“

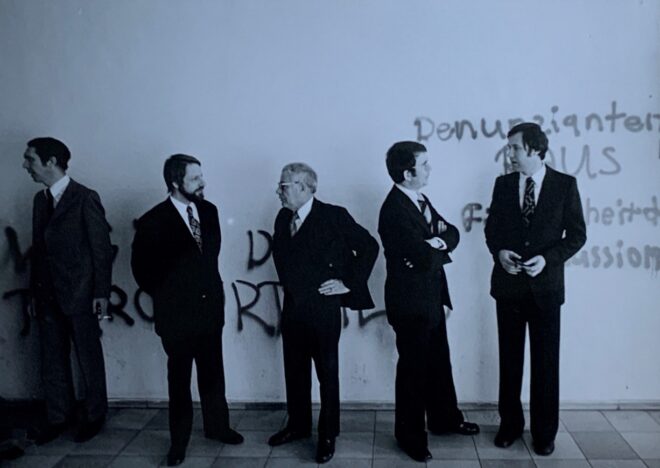

Verfassungsfeier 11. August 1929. Der Bundesvorstand des Reichsbanners vor dem Berliner Schloss.[11]

In der WRV war ein Hineinwirken des Völkerrechts in das innerstaatliche Recht angelegt, wie auch ein innerer Zusammenhang von demokratischem Rechtsstaat und internationaler Ordnung. Nach Art. 4 WRV sollten die „allgemein anerkannten Regeln des Völkerrechts“ „als bindende Bestandteile des deutschen Reichsrechts“ gelten. Dieser neue Artikel an prominenter Stelle zu Beginn des Verfassungstextes hat zunächst eine symbolische Funktion. Er verkündet den Wiedereintritt Deutschlands in die Völkergemeinschaft und markiert einen Bruch mit der Vergangenheit. Hugo Preuß formulierte in der Nationalversammlung:

„Einen geeinten, freien nationalen Staat wollen wir organisieren, aber nicht in nationalistischer Abschließung. Wie einst die jungen Vereinigten Staaten von Nordamerika in den Kreis der alten Staatenwelt eintraten mit dem Bekenntnis zur bindenden Kraft des internationalen Rechts, so bekennt sich die junge deutsche Republik […] zur Geltung des Völkerrechts.“[12]

Das war natürlich umstritten, auch in der Nationalversammlung und im Verfassungsausschuss.[13] Die Idee der „Einfügung des Reichs als demokratischer Rechtsstaat in die Völkerrechtsgemeinschaft“[14] brachte noch § 2 der Entwurfsfassungen von Preuß zum Ausdruck, der demokratisches Prinzip und verfassungsrechtlich sanktionierte Völkerrechtsbindung in ein und derselben Verfassungsbestimmung zusammenfasst.[15] In der Sache erlangte der Einzelne, dessen Beziehungen zur internationalen Gemeinschaft bislang absolut mediatisiert waren, durch Art. 4 WRV nunmehr unmittelbaren Kontakt mit dem Völkerrecht.[16] Allerdings wurde die in Art. 4 WRV angelegte „Völkerrechtsfreundlichkeit“ (Gerhard Anschütz)[17] im Schrifttum und in der gerichtlichen Spruchpraxis nach 1919 vielfach dadurch unterlaufen, dass die Wendung von den „allgemein anerkannten Regeln des Völkerrechts“ als Erfordernis der spezifischen Zustimmung des Reiches zu dem betreffenden Völkerrechtssatz interpretiert wurde.[18] Der Kommentar von Anschütz spiegelt insofern die gängige Lehrmeinung wider: Um als bindender Bestandteil des deutschen Reichsrechts zu gelten, müsse ein Völkerrechtssatz vom Deutschen Reiche „anerkannt“ sein; diese Anerkennung sei auch „frei widerruflich“.[19]

Völkerrecht jenseits der klassischen Außenbeziehungen

Bereits vor 1914 kam dem Völkerrecht im innerstaatlichen Bereich eine stetig wachsende Bedeutung zu.[20] 1891 betonte der spätere „Vater der Weimarer Verfassung“ Preuß den „innige[n] Zusammenhang“ des Völkerrechts „mit dem Wirthschaftsleben“: „Das Völkerrecht […] existirt in lebendigster Wirklichkeit; in tausend Verhältnissen des täglichen Lebens macht es seine Existenz segensreich fühlbar“.[21] Auch wenn der Erste Weltkrieg eine Zäsur bedeutete, gewannen völkerrechtliche Verträge und die Mitgliedschaft in internationalen Organisationen danach wieder an Bedeutung. Trotz allgemeiner Ablehnung des Versailler Vertrags und in der öffentlichen Meinung vorherrschenden Nationalismus war Weimar-Deutschland international eingebunden und engagiert. Insbesondere in den 1920er Jahren schloss Deutschland eine Reihe von internationalen Verträgen ab.[22] Viele von ihnen beziehen sich auf Fragen von Frieden und Sicherheit. Diesen „politischen Verträgen“ widmete das KWI eine eigene Dokumentensammlung.[23] In der Weimarer Republik wurden die Außenbeziehungen insgesamt zu einem gewissen Grad als politisch-militärische Angelegenheit verstanden.[24] Jedoch ist die Zahl der Verträge, die sich auf das tägliche Leben der Menschen und die Wirtschafts- und Sozialordnung bezogen, sogar noch größer.

So trat Deutschland 1922 etwa dem Madrider System für die internationale Registrierung von Marken bei.[25] Zu den relevanten Verträgen gehören auch das Übereinkommen und Statut über die internationale Rechtsordnung der Seehäfen von 1923,[26] der deutsch-amerikanische Freundschafts-, Handels- und Konsularvertrag von 1923[27] und das Haager Abkommen über die internationale Hinterlegung gewerblicher Muster und Modelle von 1925.[28] Mit dem Beitritt zum Übereinkommen und Statut von Barcelona über die Freiheit des Durchgangsverkehrs von 1921[29] entsprach Deutschland der Verpflichtung aus Art. 379 des Vertrags von Versailles, „jedem allgemeinen Übereinkommen über die zwischenstaatliche Regelung des Durchgangsverkehrs, der Schiffahrtswege, Häfen und Eisenbahnen beizutreten, das zwischen den alliierten und assoziierten Mächten mit Zustimmung des Völkerbunds binnen fünf Jahren […] geschlossen wird.“[30]

Besonders bedeutsam dürften in diesem Bereich jedoch die Übereinkommen der Internationalen Arbeitsorganisation (International Labour Organization, ILO) sein, deren Mitglied Deutschland seit 1919 war. Von insgesamt 63 bis einschließlich 1933 von der Internationalen Arbeitskonferenz verabschiedeten Übereinkommen ratifizierte Deutschland zwischen 1925 und 1933 immerhin 19.[31] Das internationale Arbeitsrecht hat in Deutschland allerdings stets eine relativ marginale Rolle gespielt.[32] Die Gründe dafür finden sich zum einen in den historisch älteren Wurzeln des nationalen Arbeits- und Sozialrechts, zum anderen in der Haltung gegenüber dem Versailler Vertrag, der die ILO‑Verfassung als Teil XIII enthielt. Im Rückblick erscheint diese deutsche Distanz zur ILO freilich im Spannungsverhältnis zur sozialen Programmatik[33] der Weimarer Reichsverfassung.

1926 wurde Deutschland Mitglied des Völkerbundes, was durchaus auch jenseits von Fragen von Frieden und Sicherheit sowie der Abrüstung von Bedeutung war.[34] Die 1919 eingesetzte „Kommission für neue Staaten“ erarbeitete Verträge zum Schutz von Minderheiten in den Staaten Osteuropas, die unter der Garantie des Völkerbundes standen,[35] darunter den Polnischen Minderheitenvertrag,[36] der der deutschen Minderheit in Polen zugutekam. Die Struktur des Völkerbundes umfasste die Wirtschafts- und Finanzorganisation,[37] die Gesundheitsorganisation, die Organisation für Kommunikation und Transit, das Internationale Komitee für geistige Zusammenarbeit, den Ständigen Zentralen Opiumausschuss, den Beratenden Ausschuss für Frauen- und Kinderhandel, die Flüchtlingskommission und den Ausschuss für die Untersuchung der Rechtsstellung der Frau. Freilich ist das spätere System der UN‑Charta für die internationale Zusammenarbeit auf wirtschaftlichem und sozialem Gebiet in dieser Form ohne Vorbild im Völkerbund und gilt auch als eine der Lehren, die aus dem wirtschaftlichen Chaos und den sozialen Missständen der Zwischenkriegszeit als Friedensbedrohung gezogen wurden.[38]

Die Einleitung zur Neuauflage des Völkerrechtslehrbuchs von Franz von Liszt von 1925 gab einen Überblick über die durch die „geänderten Verhältnisse“ bedingten neuen Themen des Völkerrechts, unter anderem Mandatssystem, Binnenschifffahrt, internationaler Arbeitsschutz, Völkerbund, Kriegsverhütung einschließlich Abrüstung sowie Ständiger Internationaler Gerichtshof (StIGH).[39] Eine Durchsicht der Bände 1‑3 (1929‑1933, insgesamt mehr als 2.300 Druckseiten) der ZaöRV bestätigt diesen Befund dagegen nur teilweise;[40] insbesondere ist er in der systematischen Untergliederung der „Ersten Abteilung: Völkerrecht“ nicht abgebildet.

Deutschland war auch maßgeblich an der internationalen Streitbeilegung beteiligt. In den 1920er Jahren war Deutschland im Allgemeinen vor dem StIGH erfolgreich, insbesondere im Hinblick auf die deutschen Interessen und Minderheitenrechte in Polen.[41] Mit dem Völkerbund und dem StIGH verband sich die Hoffnung, dass die im Lichte der Erfahrungen des Ersten Weltkriegs geschaffene internationale Rechtsordnung zur Schaffung einer universellen Rechtsgemeinschaft führen würde. Diese Hoffnung beruhte – gerade für den Kriegsverlierer Deutschland – vor allem auf der legalistischen Vision einer Ordnung, in der alle Staaten der obligatorischen Schiedsgerichtsbarkeit durch einen internationalen Gerichtshof zustimmen würden.

Völkerrecht als „Rechtsordnung für die Gemeinschaft der Staaten“

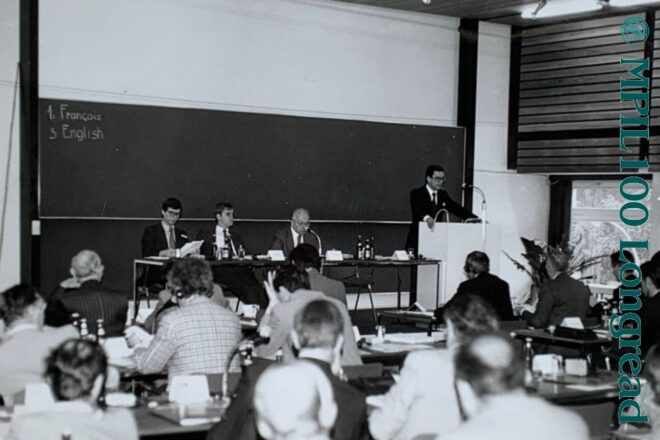

Viktor Bruns 1937 bei einem Vortrag.[42]

Hier setzt Bruns in seiner innovativen und als programmatische Grundlegung zu verstehenden Schrift in der ersten Ausgabe der ZaöRV von 1929 an. Zwischen 1927 und 1932 war er selbst als Richter ad hoc am StIGH und als nationaler Richter am deutsch‑polnischen Gemischten Schiedsgericht und am deutsch‑tschechoslowakischen Gemischten Schiedsgericht tätig und vertrat die deutsche Regierung in verschiedenen Fällen vor dem StIGH.[43] Nun arbeitet er den Charakter des Völkerrechts als autonome Rechtsordnung heraus, die nicht auf der Souveränität, sondern auf der „Rechtsgemeinschaft“ der Staaten beruht: „Das Völkerrecht ist eine Rechtsordnung für die Gemeinschaft der Staaten, ein System von Rechtsgrundsätzen, Rechtsinstituten und Rechtssätzen, die untereinander in einem Ordnungszusammenhang stehen.“ Dies lässt sich als Weiterentwicklung der Lehre Heinrich Triepels vom Gemeinwillen verstehen.[44] In bemerkenswerter Weise überträgt Bruns dazu die Vorstellung von Carl Schmitt zum Verhältnis von „geschriebene[r] Verfassung“ und „deutsche[r] Rechtsgemeinschaft“ auf die Völkerrechtsordnung. „Ganz ebenso“ könne die Rechtsnatur der Verträge in der Staatengemeinschaft nicht aus dem Selbstverpflichtungswillen der Staaten im Einzelfall, sondern nur aus der Rechtsordnung der zu einer Rechtsgemeinschaft zusammengeschlossenen Staaten gefolgert werden: „Recht einer Rechtsgemeinschaft sind alle sich aus der konkreten Ordnung dieser Gemeinschaft ergebenden rechtlichen Folgerungen und Voraussetzungen.“[45] Die Bedeutung dieser Rechtsordnung für die Einzelnen greift Bruns indes nicht auf. Er thematisiert weder die Innovationen der Reichsverfassung mit Bezug zum Völkerrecht noch die Bedeutung des zeitgenössischen Völkerrechts jenseits der klassischen Außenbeziehungen.

Dass dadurch eine durchaus signifikante Lücke zwischen „ausländischem öffentlichen Recht“ und „Völkerrecht“ klaffte, wird – zugegebenermaßen retrospektiv, with the benefit of hindsight, zumal aus der Warte der offenen Staatlichkeit des Grundgesetzes – besonders deutlich. Sicherlich aber hätte ein Forschungsinstitut mit mehr Distanz zum politischen Betrieb auch ein anderes Forschungsprogramm entwickelt. Zugleich muss man sich vergegenwärtigen, wie kurz die Weimarer Jahre des Instituts waren, wie kurz auch die deutsche Mitgliedschaft im Völkerbund war – und wie dominant der „Kampf gegen Versailles“ für die deutsche Völkerrechtswissenschaft. Es war nicht der Moment für die praktische „Vollendung der Genossenschaftsidee im Völkerrecht“,[46] wie sie Preuß angedacht hatte. Dabei bot sich der Genossenschaftsgedanke, wie zuletzt im Nachgang zum Jubiläum der Verfassung von 1919 erinnert wurde, theoretisch auch für eine völkerrechtliche Gemeinschaftsordnung an: So wie die demokratische Verfassung die Anerkennung von Pluralismus und Rechtsstaatlichkeit im Inneren erforderte, so verlangte sie auch ein neues Verständnis des Staates als einen unter vielen, der zu kooperieren habe. Die theoretische wie praktische Kontinuität von inneren und äußeren Verhältnissen reflektiert zwar nicht die völkerrechtliche Schrift des KWI-Direktors, wohl aber das Eingangszitat des späteren Bauhausdirektors: „Gewerkschaft, Genossenschaft, A. G., G. m. b. H., Kartell, Trust und Völkerbund sind die Ausdrucksformen heutiger gesellschaftlicher Ballungen, […]. Kooperation beherrscht alle Welt.“

[1] Hannes Meyer, Die Neue Welt, Das Werk 13 (1926), 205-224 (205, 221, 222), Herv. i.O.

[2] Felix Lange, Between Systematization and Expertise for Foreign Policy, EJIL 28 (2017), 535-558 (537, 543); Ingo Hueck, in: Doris Kaufmann (Hrsg.), Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven der Forschung, Göttingen: Wallstein 2000, 490-491; Rüdiger Hachtmann, Das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht 1924 bis 1945, MPIL100.

[3]„Völkerrecht als Rechtsordnung? Das KWI zwischen Wissenschaft und Politikberatung“ – So der Titel eines Panels am 15.6.2023 im Rahmen der interdisziplinären Seminarreihe „100 Jahre öffentliches Recht“ zur Geschichte des MPIL.

[4] Für die Kultur: Peter Gay, Die Republik der Außenseiter: Geist und Kultur in der Weimarer Zeit 1918-1933, Berlin: Fischer 1989, 25.

[5] Siehe: Dieter Grimm, 100 Jahre Öffentliches Recht, MPIL100.

[6] Carlo Schmid, Erinnerungen, Stuttgart: S. Hirzel 2008, 120.

[7] Frank Schorkopf, Staatsrecht der internationalen Beziehungen, München: C.H. Beck 2017, § 10 Rn. 87.

[8] Albert Hänel, Deutsches Staatsrecht, Bd.1, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot 1892, 531–562; vgl. Schorkopf (Fn. 7), § 10 Rn. 14.

[9] Ruth D. Masters, The Relation of International Law to the Law of Germany, Political Science Quaterly 45 (1930), 359-394 (359).

[10] Viktor Bruns, Völkerrecht als Rechtsordnung I, ZaöRV 1 (1929), 1-56.

[11] BArch, Bild 102-08214 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

[12] Verhandlungen der verfassungsgebenden Deutschen Nationalversammlung, Bd. 326, Stenographische Berichte 1920, 286A (Protokoll der 14. Sitzung, 24.2.1919).

[13] Laila Schestag, Weimar International, Jahrbuch des öffentlichen Rechts der Gegenwart 2022, 373-413 (393–396), m.N.

[14] Hugo Preuß, Reich und Länder. Bruchstücke eines Kommentars zur Verfassung des Deutschen Reiches, Köln: C.Heymann 1928, 82.

[15] Vorentwurf (Entwurf I) datiert 3.1.1919; Entwurf des allgemeinen Teils der künftigen Reichsverfassung (Entwurf II), datiert 20.1.1919; s. dazu Schestag (Fn. 12), 400–402, m.w.N.

[16] Preuß (Fn. 13), 86-87; s. auch Alfred Verdross, Reichsrecht und internationales Recht. Eine Lanze fur Art. 3 des Regierungsenwurfes der deutschen Verfassung, Deutsche Juristen-Zeitung 24 (1919), 291-293 (292–293); Gerhard Anschütz, Die Verfassung des Deutschen Reichs. Ein Kommentar für Wissenschaft und Praxis, Berlin: Georg Stilke 1933, Art. 4, 62-63.

[17] Anschütz (Fn. 15), 68.

[18] Thilo Rensmann, Die Genese des “offenen Verfassungsstaats” 1948/49 in: Thomas Giegerich (Hrsg.), Der „offene Verfassungsstaat“ des Grundgesetzes nach 60 Jahren, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2010, 37-58 (44-46); Rechtsprechungsnachweise bei: Lawrence Preuss, International Law in the Constitutions of the Länder in the American Zone in Germany, AJIL 41 (1947), 888-899 (893–895).

[19] Anschütz (Fn. 15), 65, 68.

[20] Peter Caldwell, Sovereignty, Constitutionalism, and the Myth of the State: Article Four of the Weimar Constitution, in: Leonard V. Kaplan/Rudy Koshar (Hrsg.), The Weimar Moment. Liberalism, Political Theology, and Law, Lanham: Lexington Books 2012, 345-370 (350).

[21] Hugo Preuß, Das Völkerrecht im Dienste des Wirthschaftslebens, Berlin: L. Simion 1891, 4-5.

[22] Wikipedia: Treaties of the Weimar Republic.

[23] Viktor Bruns (Hrsg.), Politische Verträge: Eine Sammlung von Urkunden, 3 Bde, Berlin: Carl Heymann 1936–1942.

[24] Gaines Post, The Civil-Military Fabric of Weimar Foreign Policy, Princeton: Princeton University Press 2015.

[25] Madrider Abkommen über die internationale Registrierung von Marken, 14.4.1891, RGBl. 1922 II S. 669.

[26] Übereinkommen und Statut über die internationale Rechtsordnung der Seehäfen, 9.12.1923, RGBl. 1928 II S. 23.

[27] Freundschafts-, Handels- und Konsularvertrag, 8.12.1923, RGBl. 1925 II S. 795.

[28] Haager Abkommen über die internationale Hinterlegung gewerblicher Muster und Modelle, 6.11.1925, RGBl. 1928 II S. 175, 203.

[29] Übereinkommen und Statut über die Freiheit des Durchgangsverkehrs, 14.4.1921, RGBl. 1924 II S. 387.

[30] Friedensschluß zwischen Deutschland und den alliierten und assoziierten Mächten (Versailler Vertrag), 28.6.1919, RGBl. 1919 S. 687.

[31] International Labour Organization, Ratifications for Germany, m.N.

[32] Sandrine Kott, Dynamiques de l’internationalisation: l’Allemagne et l’Organisation internationale du travail (1919-1940), Critique Internationale 52 (2011), 69-84 (71).

[33] Michael Stolleis, Die soziale Programmatik der Weimarer Reichsverfassung, in: Horst Dreier/Christian Waldhoff (Hrsg.), Das Wagnis der Demokratie: Eine Anatomie der Weimarer Reichsverfassung, München: C.H. Beck 2018, 195-218.

[34] League of Nations, The Development of International Co-operation in Economic and Social Affairs: Report of the Special Committee (Bruce Report) 1939, L.o.N. A.23.1939; vgl. Patricia Clavin, Securing the World Economy: The Reinvention of the League of Nations, 1920-1946, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2013.

[35] Carl Georg Bruns, Die Garantie des Völkerbundes über die Minderheitenverträge, ZaöRV 2 (1931), 3-16.

[36] Minderheitenschutzvertrag zwischen den Alliierten und Assoziierten Hauptmächten und Polen, 28.6.1919, CTS 225, 412.

[37] S. dazu: Patricia Clavin/Jens-Wilhelm Wessels, Transnationalism and the League of Nations, Contemporary European History 14 (2005), 465-492; Yann Decorzant, La Société des Nations et l’apparition d’un nouveau réseau d’expertise économique et financière (1914–1923), Critique International 3 (2011), 35-50.

[38] Mohammed Bedjaoui, Article 1 (commentaire général), in: Jean-Pierre Cot/Alain Pellet, La Charte des Nations Unies. Commentaire article par article, Paris: Economica 2005, 318.

[39] Franz von Liszt (Hrsg.), Das Völkerrecht: systematisch dargestellt, Berlin: Verlag Julius Springer 1925, IV-V.

[40] S. insb. André N. Mandelstam, Der internationale Schutz der Menschenrechte und die New-Yorker Erklärung des Instituts für Völkerrecht, ZaöRV 2 (1931), 335-377.

[41] Ole Spiermann, International Legal Argument in the Permanent Court of International Justice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2005, 292.

[42] AMPG, Bruns Viktor II 3.

[43] Lange (Fn. 2), 540.

[44] Heinrich Triepel, Völkerrecht und Landesrecht, Leipzig: C.L. Hirschfeld 1899, 32-33, 88 (diese Anbindung macht Bruns, langjähriger Berliner Fakultätskollege von Triepel, allerdings in seinem Aufsatz nicht explizit).

[45] Bruns (Fn. 10), 10–12, 1, 13.

[46] Schestag (Fn. 12), 399–403.

“Motor cars dash along our streets. […] Aircraft slip through the air […]; they disregard national frontiers and bring nation closer to nation. […] The simultaneity of events enormously extends our concept of “space and time,” it enriches our life. […] We become cosmopolitan. […] Trade union, co-operative, Lt., Inc., cartel, trust, and the League of Nations are the forms in which today’s social conglomerations find expression […]. Co-operation rules the world. […] Each age demands its own form. […] Internationalism is the prerogative of our time.”[1]

This quote is not from the Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (ZaöRV, English title: Heidelberg Journal of International Law), but from the 1926 essay “The New World” (“Die Neue Welt”) by the architect and urbanist Hannes Meyer. Meyer worked at the Bauhaus from 1926 to 1930, ultimately as director. In 2023/24, we are not only celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, but also the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus exhibition in Weimar. At the Bauhaus, the positioning between theory and practice was a fundamental conflict. Founded in 1924, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (KWI) for Comparative Public Law and International Law, founded in 1924, was to deal with the legal issues in its field of activity from a practice‑orientated and dogmatic perspective. This positioning is crucial for understanding the Weimar years of the Institute under the directorship of Viktor Bruns. On the one hand, the aim was to promote international law as a legal system and to raise the standard of international law scholarship in Germany. On the other hand, the legal expertise gathered at the KWI was seen as an important factor in Germany’s positioning vis-à-vis the Treaty of Versailles.[2] In this respect, the KWI was also situated between theory and practice or “between scholarship and political advicesory”.[3]

Apart from these parallels, Meyer’s text is of interest for understanding the KWI in the Weimar years for another reason: The text bears witness to a perceived internationalism in the mid-1920s, which will not have been representative, but nonetheless formative. Internationality in art and culture, but also in the economy, was already very advanced before the First World War; the war destroyed many of these connections.[4] However, internationality could be perceived and experienced in many ways by individuals in everyday life during the Weimar years. In contrast, the KWI’s agenda remained essentially focussed on foreign relations in the classic intergovernmental sense. This corresponded to the “boundary” “sharply drawn” also by contemporaries between international law and constitutional law.[5] The Institute was not intended to deal solely with international law, as the possible application of international law in practice largely depended on the constitutional constraints of the states. It therefore seemed necessary to include foreign public law in the research.[6] Accordingly, “comparative public law” and “international law” are not only part of the name of the KWI, but also of Beiträge zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht (“Contributions on Comparative Public Law and International Law”), which was founded in 1927, and ZaöRV, which has been published since 1929.

Consequently, the focus was not on the domestic constitutional law of foreign relations of the 1919 Weimar Constitution, which was innovative also in this respect. In the 1920s, “constitutional law of foreign relations” (“Außenverfassungsrecht”) was not yet established as a field of research. As a university subject (“Staatsrecht III”) and subject of publications, constitutional law of foreign relations only emerged much later, in the Federal Republic of Germany in the mid-1970s.[7] However, the legal concept of “foreign affairs” (“auswärtige Gewalt”) had already become established with Albert Hänel’s textbook published in 1892[8] and contemporaries were aware that the question of the relationship between international law and domestic law was becoming increasingly important in view of the multiplication of international points of contact.[9] Obviously, no institute for “international law and national law” was founded in 1924. Nevertheless, the observation is not trivial: with the orientation of the institute, a perspective on “international law as a legal system” in itself[10] was lost. This concerns its – potential – significance for individuals, its impact on the domestic legal and social order under the new constitution, as well as its connection with the democratic process and its significance for judicial practice. A programmatic gap emerged between “comparative public law” and “international law”. At the same time, the significance of international law beyond traditional foreign relations was obscured.

Innovative Weimar “Constitutional Law of Foreign Relations”

Verfassungsfeier (“Constitution Day”) on 11 August 1929. The Federal Board of the Reichsbanner (“Banner of the Reich”, an anti-fascist political organization) in front of the Berlin Palace.[11]

The Weimar Constitution embraced an influence of international law on domestic law, as well as an inherent connection between the democratic constitutional state and the international order. According to Article 4, the “rules of international law, universally recognized” were “deemed to form part of German federal law and, as such, have obligatory force”.[12] This new article in a prominent position at the beginning of the constitutional text initially had a symbolic function. It proclaims Germany’s re-entry into the community of nations and marks a break with the past. Hugo Preuß formulated in the National Assembly:

“We want to organise a united, free, and national state, but not in nationalist isolation. Like once the young United States of North America entered the circle of the old world of states with a commitment to the binding force of international law, the young German Republic commits […] to the validity of international law.”[13]

This was of course controversial, also in the National Assembly (Nationalversammlung) and the Constitutional Committee (Verfassungsausschuss).[14] The idea of the “integration of the Reich as a democratic constitutional state into the community of international law”[15] was still expressed in Section 2 of the draft versions by Preuß, which summarised the democratic principle and constitutionally sanctioned commitment to international law in one and the same constitutional provision.[16] Materially, the individual, whose relations with the international community had hitherto been completely mediatised, was, by Article 4 of the new constitution, brought into direct contact with international law.[17] However, this “Völkerrechtsfreundlichkeit” (a term coined by Gerhard Anschütz, that can loosely be translated to “openness towards international law”)[18] laid down in Art. 4 WRV was often undermined in the legal literature and in court practice after 1919 by the interpretation of “rules of international law, universally recognized” as requiring the specific consent of the Reich to the relevant rule of international law.[19] In this respect, Anschütz’s commentary reflects the prevailing doctrine: In order to be considered a binding component of German federal law, a rule of international law must be “recognised” by the German Empire and this recognition is “freely revocable”.[20]

International Law Beyond Traditional Foreign Relations

Even before 1914, international law was becoming increasingly important in the domestic sphere.[21] In 1891, Hugo Preuß, who was later to become a “father of the Weimar Constitution” emphasised the “intimate connection” of international law “with economic life”: “International law […] exists in the most vivid reality; in a thousand circumstances of daily life, it makes its existence gloriously perceivable”.[22] Even though the First World War marked a turning point, international treaties and membership in international organisations regained importance afterwards. Despite the general rejection of the Treaty of Versailles and the nationalism prevailing in public opinion, Weimar Germany was internationally integrated and engaged. In the 1920s in particular, Germany concluded a number of international treaties,[23] many of them related to issues of peace and security. The KWI dedicated a separate collection of documents to these “political treaties”.[24] In the Weimar Republic, foreign relations as a whole were understood to a certain extent as a political-military matter.[25] However, the number of treaties relating to people’s daily lives and the economic and social order was even greater.

For example, Germany joined the Madrid System for the international registration of trademarks in 1922.[26] The relevant treaties also include the Convention and Statute on the International Régime of Maritime Ports of 1923,[27] the German-American Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Consular Relations of 1923,[28] and the Hague Agreement Concerning the International Deposit of Industrial Designs of 1925.[29] By acceding to the Barcelona Convention and Statute on Freedom of Transit of 1921[30], Germany fulfilled its obligation under Art. 379 of the Treaty of Versailles “to adhere to any General Conventions regarding the international regime of transit, waterways, ports or railways which may be concluded by the Allied and Associated Powers, with the approval of the League of Nations, within five years […].”[31]

Particularly significant in this area are the conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO), of which Germany had been a member since 1919. Of a total of 63 conventions adopted by the International Labour Conference up to and including 1933, Germany ratified as many as 19 between 1925 and 1933.[32] However, international labour law has always played a relatively marginal role in Germany.[33] The reasons for this can be found, on the one hand, in the historically older roots of national labour and social law and, on the other hand, in the attitude towards the Treaty of Versailles, which contained the ILO‑Constitution as part XIII. In retrospect, however, this German distance from the ILO appears to be in tension with the social programme[34] of the Weimar Constitution.

In 1926, Germany became a member of the League of Nations, which was also significant beyond questions of peace, security and disarmament.[35] The “Commission on New States” established in 1919 drew up treaties for the protection of minorities in the Eastern European states under the guarantee of the League of Nations,[36] including the Polish Minorities Treaty,[37] which benefited the German minority in Poland. The structure of the League of Nations included the Economic and Financial Organisation,[38] the Health Organisation, the Communications and Transit Organisation, the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, the Permanent Central Opium Board, the Advisory Committee on Traffic in Women and Children, the High Commission (and later International Office) for Refugees and the Committee for the Study of the Status of Women. Admittedly, the later system of international co-operation in economic and social matters as established by the UN‑Charter is unprecedented in the League of Nations and is also regarded as one of the lessons learnt from the economic chaos and social ills of the interwar period as a threat to peace.[39]

The introduction to the new edition of Franz von Liszt’s 1925 textbook on international law provided an overview of the new topics of international law resulting from the “changed circumstances”, including the mandate system, inland waterway transport, international labour standards, the League of Nations, war prevention including disarmament and the Permanent International Court of Justice.[40] A review of volumes 1‑3 (1929‑1933, totalling more than 2,300 pages) of the ZaöRV only partially confirms this finding however;[41] in particular, it is not reflected in the systematic subdivision of the “First Division: International Law”.

Germany was also significantly involved in international dispute settlement. In the 1920s, Germany was generally successful before the Permanent International Court of Justice, particularly with regard to German interests and minority rights in Poland.[42] The League of Nations and the Permanent Court of International Justice were associated with the hope that the international legal order created in the light of the experiences of the First World War would lead to the creation of a universal legal community. This hope was based – especially for Germany as the loser of the war – above all on the legalistic vision of an order in which all states would agree to compulsory arbitration by an international court.

International Law as a “Legal Order for the Community of States”

Viktor Bruns during a presentation in 1937.[43]

This is where Bruns comes in with his innovative article in the first issue of the ZaöRV of 1929, which is to be understood as a programmatic foundation. Between 1927 and 1932, he himself served as an ad hoc judge at the Permanent International Court of Justice and as a national judge at the German-Polish and the German‑Czechoslovakian Arbitral Tribunals and represented the German government in various cases before the Permanent International Court of Justice.[44] He now elaborates on the character of international law as an autonomous legal order that is not based on sovereignty, but on the “legal community” of states: “International law is a legal order for the community of states, a system of legal principles, legal institutions and legal rules that are interrelated in an organized system.”[45] This can be understood as a further development of Heinrich Triepel’s doctrine of the common will (Gemeinwillen).[46] In a remarkable way, transfers Carl Schmitt’s idea of the relationship between the “written constitution” and the “German legal community” to the international legal order. “In the same way”, the legal nature of treaties in the community of states cannot be inferred from the will of states to fulfil their obligations in individual cases, but only from the legal order of the states that have joined together to form a legal community: “The law of a legal community is all legal consequences and prerequisites resulting from the concrete order of this community.”[47] However, Bruns does not take into account the significance of this legal order for the individual. He neither addresses the innovations of the Weimar Constitution in relation to international law nor the significance of contemporary international law beyond classical foreign relations.

The fact that there was a significant gap between “comparative public law” and “international law” becomes – admittedly retrospectively, with the benefit of hindsight – particularly obvious from the perspective of the openness to international law of the Grundgesetz (Basic Law). However, a research institute with more distance from politics would certainly have developed a different research programme. At the same time, one must bear in mind how short the Weimar years of the Institute were, how short Germany’s membership of the League of Nations was – and how dominant the “struggle against Versailles” was for German international law scholarship. It was not the moment for the practical “completion of the Genossenschaftsidee [loosely: associational idea] in international law”,[48] as envisaged by Preuß. Even though, as was recently recalled in the wake of the anniversary of the 1919 constitution, this idea would have theoretically lent itself also to a community order under international law: Just as the democratic constitution required the recognition of pluralism and the rule of law at home, it also demanded a new understanding of the state as one among many that had to co-operate. The theoretical and practical continuity of internal and external relationships is not reflected in the KWI director’s essay on international law, but in the opening quote by the later Bauhaus director: “Trade union, co-operative, Lt., Inc., cartel, trust, and the League of Nations are the forms in which today’s social conglomerations find expression […]. Co-operation rules the world.”

Translation from the German original: Sarah Gebel

[1] Hannes Meyer, Die Neue Welt, Das Werk 13 (1926), 205 (205, 221, 222), translation following: The Charnel House.

[2] Felix Lange, Between Systematization and Expertise for Foreign Policy, EJIL 28 (2017), 535-558 (537, 543); Ingo Hueck, in: Doris Kaufmann (ed.), Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven der Forschung, Göttingen: Wallstein 2000, 490-491; Rüdiger Hachtmann, The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law 1924 to 1945, MPIL100.

[3] “International law as a legal order? The KWI between scholarship and political advisory” (“Völkerrecht als Rechtsordnung? Das KWI zwischen Wissenschaft und Politikberatung”, translated by the editor) was the title of a panel held on 15 June 2023 in the context of the interdisciplinary seminar series “100 Years of Public Law” on the history of the MPIL.

[4] On culture: Peter Gay, Die Republik der Außenseiter: Geist und Kultur in der Weimarer Zeit 1918-1933, Berlin: Fischer 1989, 25.

[5] See: Dieter Grimm, 100 Years of Public Law, MPIL100.

[6] Carlo Schmid, Erinnerungen, Stuttgart: S. Hirzel 2008, 120.

[7] Frank Schorkopf, Staatsrecht der internationalen Beziehungen , Munich: C.H. Beck 2017, § 10 para. 87.

[8] Albert Hänel, Deutsches Staatsrecht, vol.1, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot 1892, 531-562; cf. Schorkopf (fn 7), § 10 para. 14.

[9] Ruth D. Masters, The Relation of International Law to the Law of Germany, Political Science Quaterly 45 (1930), 359-394 (359).

[10] Viktor Bruns, Völkerrecht als Rechtsordnung I, HJIL 1 (1929), 1-56.

[11] BArch, Bild 102-08214 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

[12] Translation following: Heinrich Oppenheimer, The Constitution of the German Republic, London: Stevens and Sons 1923, Appendix: The constitution of the German Federation of August 11, 1919, 219-260.

[13] Verhandlungen der verfassungsgebenden Deutschen Nationalversammlung, vol. 326, Stenographische Berichte 1920, 286A (Minutes of the 14th session, 24 February 1919), translated by the editor.

[14] Laila Schestag, Weimar International, Jahrbuch des öffentlichen Rechts der Gegenwart 2022, 373-413 (393-396), with references.

[15] Hugo Preuß, Reich und Länder. Bruchstücke eines Kommentars zur Verfassung des Deutschen Reiches, Köln: C.Heymann 1928, 82, translated by the editor.

[16] Vorentwurf (draft I) dated 3 January 1919; Entwurf des allgemeinen Teils der künftigen Reichsverfassung (draft II), dated 20 January 1919; see Schestag (fn 12), 400-402, with further references.

[17] Preuß (fn 13), 86-87; see also Alfred Verdross, Reichsrecht und internationales Recht. Eine Lanze für Art. 3 des Regierungsenwurfes der deutschen Verfassung, Deutsche Juristen-Zeitung 24 (1919), 291-293 (292–293); Gerhard Anschütz, Die Verfassung des Deutschen Reichs. Ein Kommentar für Wissenschaft und Praxis, Berlin: Georg Stilke 1933, Art. 4, 62-63.

[18] Anschütz (fn 15), 68.

[19] Thilo Rensmann, Die Genese des „offenen Verfassungsstaats“ 1948/49 in: Thomas Giegerich (ed.), Der „offene Verfassungsstaat“ des Grundgesetzes nach 60 Jahren, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2010, 37-58 (44-46); references to legal cases: Lawrence Preuss, International Law in the Constitutions of the Länder in the American Zone in Germany, AJIL 41 (1947), 888-899 (893-895).

[20] Anschütz (fn 15), 65, 68, translated by the editor.

[21] Peter Caldwell, Sovereignty, Constitutionalism, and the Myth of the State: Article Four of the Weimar Constitution, in: Leonard V. Kaplan/Rudy Koshar (eds.), The Weimar Moment. Liberalism, Political Theology, and Law, Lanham: Lexington Books 2012, 345-370 (350).

[22] Hugo Preuß, Das Völkerrecht im Dienste des Wirthschaftslebens, Berlin: L. Simion 1891, 4-5, translated by the editor.

[23] Wikipedia: Treaties of the Weimar Republic.

[24] Viktor Bruns (ed.), Politische Verträge: Eine Sammlung von Urkunden, 3 vols, Berlin: Carl Heymann 1936-1942.

[25] Gaines Post, The Civil-Military Fabric of Weimar Foreign Policy, Princeton: Princeton University Press 2015.

[26] Madrider Abkommen über die internationale Registrierung von Marken, 14.4.1891, RGBl. 1922 II S. 669.

[27] Übereinkommen und Statut über die internationale Rechtsordnung der Seehäfen, 9.12.1923, RGBl. 1928 II S. 23.

[28] Freundschafts-, Handels- und Konsularvertrag, 8.12.1923, RGBl. 1925 II S. 795.

[29] Haager Abkommen über die internationale Hinterlegung gewerblicher Muster und Modelle, 6.11.1925, RGBl. 1928 II S. 175, 203.

[30] Übereinkommen und Statut über die Freiheit des Durchgangsverkehrs, 14.4.1921, RGBl. 1924 II S. 387.

[31] Friedensschluß zwischen Deutschland und den alliierten und assoziierten Mächten (Versailler Vertrag), 28.6.1919, RGBl. 1919 S. 687, translation following: Wikisource.

[32] International Labour Organization, Ratifications for Germany, with references.

[33] Sandrine Kott, Dynamiques de linternationalisation: l’Allemagne et l’Organisation internationale du travail (1919-1940), Critique Internationale 52 (2011), 69-84 (71).

[34] Michael Stolleis, Die soziale Programmatik der Weimarer Reichsverfassung, in: Horst Dreier/Christian Waldhoff (eds), Das Wagnis der Demokratie: Eine Anatomie der Weimarer Reichsverfassung, Munich: C.H. Beck 2018, 195-218.

[35] League of Nations, The Development of International Co-operation in Economic and Social Affairs: Report of the Special Committee (Bruce Report) 1939, L.o.N. A.23.1939; cf. Patricia Clavin, Securing the World Economy: The Reinvention of the League of Nations, 1920-1946, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2013.

[36] Carl Georg Bruns, Die Garantie des Völkerbundes über die Minderheitenverträge, HJIL 2 (1931), 3-16.

[37] Minorities Treaty between the Principal Allied and Associated Powers and Poland, signed 28 June 1919.

[38] Cf: Patricia Clavin/Jens-Wilhelm Wessels, Transnationalism and the League of Nations, Contemporary European History 14 (2005), 465-492; Yann Decorzant, La Société des Nations et l’apparition d’un nouveau réseau d’expertise économique et financière (1914-1923), Critique International 3 (2011), 35-50.

[39] Mohammed Bedjaoui, Article 1 (commentaire général), in: Jean -Pierre Cot/ Alain Pellet, La Charte des Nations Unies. Commentaire article par article, Paris: Economica 2005, 318.

[40] Franz von Liszt (ed.) , Das Völkerrecht: systematisch dargestellt, Berlin: Verlag Julius Springer 1925, IV-V .

[41] S. esp. André N. Mandelstam, Der internationale Schutz der Menschenrechte und die New-Yorker Erklärung des Instituts für Völkerrecht, HJIL 2 (1931), 335-377.

[42] Ole Spiermann, International Legal Argument in the Permanent Court of International Justice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2005, 292.

[43] AMPG, Bruns Viktor II 3.

[44] Lange (fn 2), 540.

[45] Translated by the editor.

[46] Heinrich Triepel, Völkerrecht und Landesrecht, Leipzig: C.L. Hirschfeld 1899, 32-33, 88 (this connection however, is not made explicit in his essay by Bruns, a long-time Berlin faculty colleague of Triepel)

[47] Bruns (n 10), 10-12, 1, 13, translated by the editor.

[48] Schestag (fn 12), 399-403.