Nach Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs war im deutschen Sprachraum begonnen worden, die traditionellen Ansätze des religiösen Minderheitenschutzes und der innerstaatlichen Nationalitätenpolitik Österreich-Ungarns zugunsten einer völkerrechtlichen Minderheitenpolitik aufzugreifen, wobei vor dem Hintergrund der europäischen Neuordnung infolge der Pariser Vorortverträge statt eines – bereits seinerzeit in den wesentlichen Grundzügen entstandenen – individualrechtlichen Antidiskriminierungsschutzes ein System völkisch-kollektiver Sonderrechte etabliert werden sollte. Eine entscheidende Rolle bei der theoretischen Entwicklung des ‚modernen‘ Nationalitäten- und Volksgruppenrechts spielte Hermann Raschhofer (1905–1979), der besonders mit seinen für die völkische Völkerrechtslehre bis heute prägenden Arbeiten über die Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts (1931) und Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff (1936/37) hervortrat.

Herkunft und Ausbildung

Raschhofer wurde am 26. Juli 1905 in Ried im Innkreis (Oberösterreich) geboren. Er studierte in Marburg, Wien und Innsbruck Rechts- und Staatswissenschaften, legte 1925 seine erste und 1928 seine zweite juristische Staatsprüfung ab und promovierte in Innsbruck 1927 zum Dr. rer. pol. und 1928 zum Dr. jur. Von April 1928 bis März 1930 war er Assistent am Institut für Grenz- und Auslandsstudien in Berlin-Steglitz, anschließend Assistent an der Juristischen Fakultät der Universität Tübingen. Vom Herbst 1931 bis Ende 1933 war Raschhofer Fellow der Rockefeller Foundation in Frankreich (Paris) und Italien (Turin).[1]

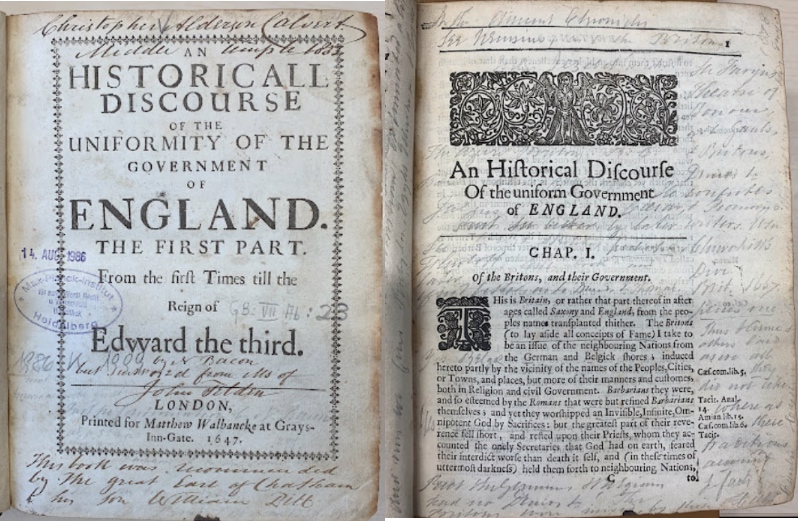

Hermann Raschhofer, 1975[2]

Raschhofers wissenschaftliche Interessen, die sich – wie er selbst schrieb – „im Zusammenhang mit praktischer Grenzlandarbeit entwickelten, galten frühzeitig dem Fragenkreis des Nationalitätenrechts.“ [3] Seine wissenschaftspolitische Orientierung wurde dabei nachhaltig durch die Wahl seines Studienortes Marburg und den dort lehrenden Johann Wilhelm Mannhardt geprägt. Mannhardt bekleidete die (eigens für ihn geschaffene) Professur für Grenz- und Auslanddeutschtum am 1919 neu initiierten Institut für Grenz- und Auslanddeutschtum an der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Marburg und war zunächst Geschäftsführer, später auch Direktor dieses Instituts.[4] Prägend wurde für Raschhofer überdies die Auseinandersetzung mit der Arbeit von Max Hildebert Boehm, zu dem er während seiner Zeit als wissenschaftlicher Assistent des Instituts für Grenz- und Auslandstudien in Berlin-Steglitz Ende der 1920er Jahre auch persönliche Beziehungen aufbaute.[5] Raschhofer übernahm in seinen wissenschaftlichen Arbeiten zum Nationalitätenrecht die Diktion von Boehm, nach der „eine Nationalität […] überall da entstehen (muss), wo durch den Nichtzusammenfall von Volks- und Staatsgrenzen ethnisch bedingte Teilgebiete erwachen, die durch Berührung mit dem Staat, also im Element der Politik eine Gestaltwerdung irgendwelcher Art gewonnen haben oder sie anstreben.“[6] Er teilte dabei Boehms euphorisches Bekenntnis zur Theorie des „eigenständigen Volks“, die die wichtigste theoretische Grundannahme für die europäische Volksgruppenpolitik der Weimarer Zeit darstellte.[7]

Raschhofer als Nationalitätenrechtler

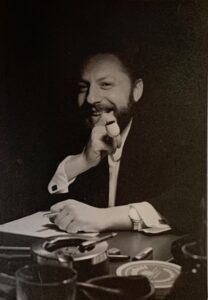

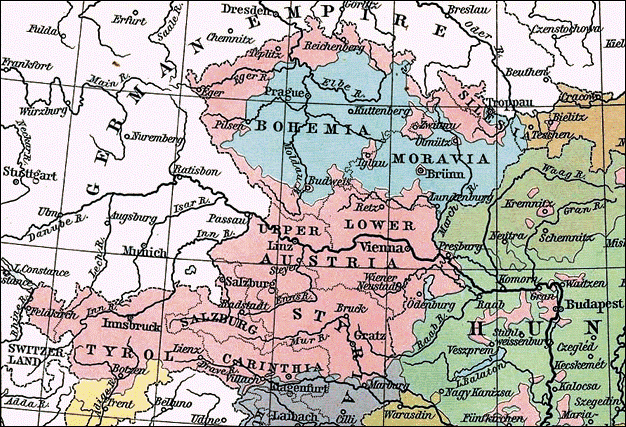

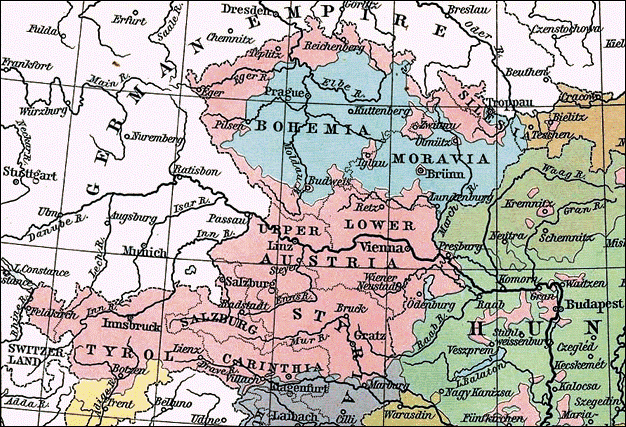

Deutschsprachige/Deutsche Minderheiten in Österreich-Ungarn (rosa gefärbt), Karte der Nationalitäten in Österreich-Ungarn (1911), The Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1911.[8]

Raschhofers erste große wissenschaftliche Arbeit mit dem Titel Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts,[9] für die er von der Deutschen Akademie (München) 1929 mit dem Ersten Preis eines Preisausschreibens über Minderheitenrecht ausgezeichnet wurde, verfolgte bereits dieses Ziel, wenngleich auch sprachlich in eher noch gemäßigtem Duktus.

Raschhofer analysierte in dieser Studie das positive internationale Minderheitenrecht und kontrastierte dieses mit den „Institutionen des Nationalitätenrechtes“ (5), also denjenigen Rechtsinstrumenten, die die nationalitätenrechtlichen Protagonisten innerstaatlich und völkerrechtlich an die Stelle des liberal-demokratischen Minderheitenrechts setzen wollten. Dabei sollte es stets um die „Rechte der Nationalität als Volkspersönlichkeit“ gehen, mit dem Ziel der Schaffung einer „Verfassung als Körperschaft des öffentlichen Rechts“ (76).

Raschhofer wandte sich damit explizit gegen die – wie er sie nannte – „Großpariser Minderheitenschutzverträge“, die er dahingehend kritisierte, dass „die Nationalitäten unter dem Rechtszustand von atomisiert gedachten nationalen Individuen unter Minderheitenrecht leben müssen“, ohne dabei als „organische Persönlichkeiten“ anerkannt zu werden (76f.) bzw. ohne als „Rechtspersönlichkeit selbst anerkannter Träger von Recht“ zu sein (78):

„Nationalität ist [..] nicht Eigenschaft, die zufällig bei diesen und jenen Staatsbürgern per se auftritt und diese sozusagen erst nachträglich zusammenführt, wie sich etwa die Mitglieder eines Vereins zur Vertretung irgendwelcher Interessen durch Assoziation ursprünglich sich Fremder zusammenfinden; sie ist nicht Summe, sondern Totalität.“ (77)

Von Nationalität ist also in diesem Verständnis nur dann zu sprechen, wenn – wie Raschhofer schrieb – „ihre Mitglieder gruppenhaft-organisch, und zwar als historisch-kulturell positiv qualifizierbare Volksgruppen erscheinen.“ (77)

Das zu erstrebende Nationalitätenrecht schütze „wohlerworbene Berechtigungen“ und verlange unumstößlich den Zusammenhang von „Boden und Geschichte“ (77). Das von Raschhofer postulierte „Wesen der Nationalität“ erfordere dabei die rechtliche Möglichkeit „im eigenen Bereich eigener Herr zu sein, also Autonomie“ (154).

In diesem seinem ersten großen Entwurf zum Thema Nationalitätenrecht entwickelte Raschhofer einen Begriff von Nationalität als „Totalität“ (77) mit „heiligen Rechten“ (156), den er explizit von dem Begriff der Minderheit abgrenzte. Da Raschhofer von einem essentialistischen bzw. primordialen Ethnizitätsbegriff ausging, erschienen für ihn Volk bzw. Volksgruppe und Nationalität stets als nicht weiter zu beweisende, übernatürliche Existenzen, deren attestierbare Unterschiede er nicht als historisch entstanden und somit veränder- und aufhebbar interpretierte, sondern als substanzielle ethnische, kulturelle und auch „rassische“ Differenz. Die damit zur Faktizität erklärte Ethnizität stellte wiederum die Grundlage für Raschhofers nationalitätenrechtliches Modell dar. Hiernach sollte Nationalitätenrecht stets am Kollektiv als Rechtssubjekt orientiert sein und um die Schaffung von exklusiven Sonderrechten für die Nationalitäten gegenüber der Restbevölkerung bemüht. Hier zeigte sich bereits deutlich Raschhofers fundamentale Gegnerschaft zum bürgerlichen Nationalstaat und zur liberalen Minderheitenpolitik des Völkerbundes – denn während der bürgerliche Nationalstaat gerade als Einheit seiner Staatsangehörigen mit gleichen Rechten konzipiert ist, waren die nach Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs geschlossenen Minderheitenschutzverträge mit dem Ziel des individuellen Schutzes vor Diskriminierungen geschaffen worden.

Raschhofer am KWI

Festschrift zum 25-jährigen Bestehen der KWG 1936: Hermann Raschhofer, Asche Graf Mandelsloh, Adolf Schüle und Viktor Bruns vertreten das Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht

Mit der Schrift Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts begründete Raschhofer sein wissenschaftliches Profil als Nationalitätenrechtler. Nach seinen Lehr- und Forschungstätigkeiten am Berliner Institut für Grenz- und Auslandsstudien, in Tübingen, Paris und Turin gelangte der junge Doppeldoktor schließlich über Erich Kaufmann an das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (KWI) in Berlin. Raschhofer wurde im Januar 1934 Referent am KWI und blieb dies bis Oktober 1937. Die Zeit am KWI war für ihn sehr wichtig, da er sein Renommee als Experte in Nationalitätenfragen nachhaltig ausbauen konnte. So schrieb er in der Jubiläumsausgabe zum 25-Jährigen Bestehen der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft 1936 den Institutsbeitrag zum Thema Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff, was neben der großen Auszeichnung für ihn eben auch die weitere Popularisierung seiner Thesen bedeutete.[10]

Dieser Aufsatz, der auch separat in Buchform erschien, ist vor allem deshalb bemerkenswert, weil Raschhofer darin seine Thesen aus Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts zuspitzt und dabei die völkische Fundierung der Theorie des Nationalitätenrechts deutlich zum Ausdruck bringt. Raschhofer versteht unter Nationalität nun eine „völkische Gruppe, die den Einzelnen als Glied einer Teilgruppe von den übrigen Staatsangehörigen unterscheidet“, ja eine „völkische Wesenheit“.[11] Die Bindungen des einzelnen an dieses Kollektiv sind seiner Auffassung nach als „vorgängig, objektiv und zugleich prägend“ anzusehen (20), wobei der Nationalität ein „naturhafter Zug“ eigen sei, nämlich „das Moment des Dauerns, das Ruhen im Vorgeschichtlichen.“ (21)

Nationalität sei ein zu einer „Artgemeinschaft gehörendes Teilganzes“, ein „Teilstück“ einer „blutmäßig begründeten Artgemeinschaft“ (44), weshalb das Bekenntnis zur Volksgemeinschaft und zur Nationalität auch nichts Neues begründe, sondern lediglich bereits vermeintlich objektiv Vorhandenes „willensmäßig“ (44) unterstreiche:

„Im Bereich des Völkischen gibt es nur ein Ja-Sagen zu seiner eigenen einzigen oder der vorherrschenden Art und das Anormale des theoretisch wie praktisch möglichen Falles eines Nein-Sagens zur eigenen Art, wird von der Sprache hinreichend mit dem verurteilenden Wort Entartung gekennzeichnet.

Es gibt daher wesensmäßig einen objektiv umgrenzten Kreis derer, die sich zu einem Volkstum, zu einer Nationalität als Artgemeinschaft bekennen können. Wenn die Nürnberger Gesetze eine solche Begrenzung getroffen haben, indem sie Artfremde und Artverwandte nunmehr endgültig scheiden, wobei den jüdischen Mischlingen, in denen das Deutschblütige überwiegt, ein Aufgehen im Deutschtum ermöglicht wurde, so kann nur hoffnungslos liberales Besserwissen dies als ein den Interessen der Volksgruppen abträgliches Vorgehen bezeichnen.“ (45)

Die bereits in seiner Arbeit Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts anklingende Konfrontation mit dem bürgerlichen Nationalstaat wird in Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff offen artikuliert. Der bürgerliche Nationalstaat gilt Raschhofer nun als „Zwangsapparat“, wobei er die Staatsbürgerschaft gegenüber der Nationalitätenzugehörigkeit abqualifiziert, da erstere „keine primäre, soziologisch gesehen urständige Größe darzustellen braucht“ (16), wohingegen letztere aufgrund ihrer „Ursprünglichkeit und Selbständigkeit als gesellschaftliches Gebilde, als reale Gruppe“ gekennzeichnet sei und sich damit „wesensmäßig vom abstrakten Staatsvolk“ unterscheide (17) – was Raschhofer auch zur Unterscheidung von staatlicher „Rechtsgemeinschaft“ und „Volksgemeinschaft“ (17) führt.

Während Raschhofer in den Hauptproblemen des Nationalitätenrechts argumentativ noch auf eine annährend gleichrangige Wertigkeit von Staat und Volk orientiert, wobei den Nationalitäten mehr Rechte zuerkannt werden müssten, gerät der nicht-völkische Staat in Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff nun vollends in die negative, sich quasi gegenüber den Nationalitäten rechtfertigen müssende Rolle. Denn unabhängig davon, ob eine Rechtsordnung die Existenz von Nationalitäten anerkenne oder verneine, so Raschhofer, könne dies nicht als objektive soziologische Entscheidung gelten, da die juristische Sicht auf den Gegenstand keinen sozialwissenschaftlichen Erkenntniswert intendiere:

‚Die „Definition des Volkes, der Nationalität [aus Perspektive des juristischen Nationalitätsbegriffs]“, kann nie die Frage nach deren Wesen beantworten. Er muß das mehrdimensionale, vielverschlungene, Vorder- und Hintergrundschichten, reflektierende und träumende Dasein umfassen, Blut und Geschichte, von Interessen, Gewohnheit, Begeisterung und Opfern zusammengehaltene Gebilde der konkreten Nationalität auf die Eindimensionalität eines auf individuellen Willensakten beruhenden rechtlichen Verbandes bringen.‘ (43)

Dem bürgerlichen Nationalstaat soll de facto die Möglichkeit zur Nicht-Anerkennung von Nationalitäten im völkisch-kollektiven Sinn entzogen werden, da einer diese angebliche Faktizität des Völkischen nicht-anerkennenden Rechtsordnung die Legitimation für ihr Handeln abgesprochen wird. Die juristische Methode wird damit genau umgekehrt und der rechtspositivistische Ansatz aufgrund des Prinzips, dass das angeblich übernatürliche und konsistente Recht der völkisch verstandenen Volksgruppen das positive Recht breche, durch eine naturrechtliche Perspektive in voraufklärerischer Tradition ersetzt.

Raschhofer schärfte in seiner Zeit beim KWI jedoch nicht nur sein Profil als regimetreuer Nationalitätenrechtler, sondern auch als Vordenker in dieser Frage, da seine Schriften zum Nationalitätenrecht zu den ersten überhaupt zählen, in denen eine (völker)rechtliche Perspektive mit der völkischen – Raschhofer selbst unterstellt diese als „soziologisch“ – mit dem Ziel verschmolzen wird, ein homogenes Modell eines „modernen“ Volksgruppen- bzw. Nationalitätenrechts als verbindlichen Entwurf für die Rechtsordnung Europas zu formulieren.

Zudem fällt seine Zeit am KWI zusammen mit seiner Habilitation im Februar 1937 (und der Ernennung zum Dr. jur. habil. im Juli 1937) an der Universität Berlin bei dem Völkerrechtler Viktor Bruns, dem Direktor des KWI. Raschhofer habilitierte sich mit dem Buch Der politische Volksbegriff im modernen Italien.[12] Sein wissenschaftlicher Werdegang wurde damit erfolgreich fortgesetzt und Raschhofer übernahm unmittelbar nach seiner Habilitation auch gleich eine bis 1939 dauernde Vertretung in Göttingen,[13] wobei ihm auch ein Angebot des Auswärtigen Amtes vorgelegen hatte, als „Presseattaché bei einer der europäischen Botschaften des Reiches einzutreten“.[14]

Raschhofer als nationalsozialistischer Rechtspraktiker und Aktivist

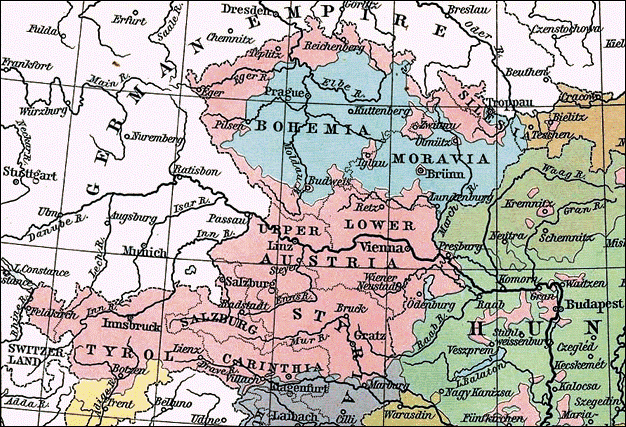

Reinhard Heydrich, stellvertretende Reichsprotektor in Böhmen und Mähren mit Karl Hermann Frank im Prager Schloss 1941[15]

Parallel zu seiner wissenschaftlichen Karriere arbeitete Raschhofer an der praktischen Umsetzung seiner Handlungsmaximen: „In den letzten Jahren trat zu den theoretischen Studien eine praktisch beratende Tätigkeit für deutsche Volksgruppen im Ausland in Fragen des positiven Minderheiten- und Staatenrechts“, resümierte er seine Tätigkeiten Mitte der 1930er Jahre rückblickend.[16] Und in einer Auseinandersetzung mit Boehms Arbeit zum „eigenständigen Volk“ schrieb Raschhofer, dass der Gegenstand „Volk“ sich „zugleich als Objekt wissenschaftlicher, soziologisch-volkstheoretischer Bemühungen, wie als Subjekt und Objekt praktischer Politik“ darstellen würde,[17] was zweifelsfrei auch seine eigenen Integration von völkischer Theoriebildung und volkstumspolitischer Praxis widerspiegelte.

Denn Raschhofer war Mitglied der illegalen NSDAP Österreichs, des VDA, des NS-Juristenbundes und des NS-Dozentenbundes. Anfang der 1930er Jahre hatte seine rechtspolitische Beratungstätigkeit für die illegale NSDAP Österreichs und für die Sudetendeutsche Partei (SdP) begonnen.[18] Insbesondere seine aus engen Kontakten zu Konrad Henlein und Karl Hermann Frank resultierende Nähe zur Politik der Sudetendeutschen legte den Grundstein für seine Berufung nach Prag: Raschhofer übernahm 1940 zunächst eine außerordentliche, später dann eine ordentliche Professur an der Deutschen Universität Prag, wo er das Institut für Völker- und Reichsrecht leitete und hätte 1944 auch Dekan der Juristischen Fakultät werden sollen, lehnte dies aber ab, da er „zuviel andere Aufträge“ gehabt habe.[19]

Raschhofers Berufung an die Deutschen Universität Prag erfolgte auf persönlichen Wunsch von Karl Hermann Frank, dessen juristischer Berater Raschhofer wurde und mit dem er durch persönliche Freundschaft eng verbunden war.[20] Frank hatte sich bereits im April 1939 dafür stark gemacht, Raschhofer nach Prag zu berufen, da dieser sowohl ihm wie auch Konrad Henlein seit 1934 politisch-wissenschaftlich beratend zur Seite gestanden hatte und künftig im Protektorat als Berater in besonderen Rechtsfragen firmieren sollte.[21] Raschhofer habe, so Frank, „wertvolle Beiträge nicht nur zur Auseinandersetzung mit der Feindpropaganda, sondern auch zur Bekämpfung der tschechischen Staats- und Geschichtsauffassung geliefert.“[22]

Überhaupt war Raschhofers Nähe zum NS-Regime unzweifelhaft. Der Reichsdozentenbundsführer bescheinigte ihm 1938, dass er „politisch gesehen“ ein „entschiedener Volksdeutscher“ sei und auch „innenpolitisch die nationalsozialistischen Gedankengänge“ bejahe.[23] Raschhofer hatte 1933 die Machtübernahme der Nationalsozialisten ebenso begrüßt, wie später den Anschluss Österreichs und der Sudetengebiete an das Deutsche Reich.[24]

Raschhofer in den „Beiträgen zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht“

Einen Grundstein für die Destablilisierung der Tschechoslowakei durch die NS-Propaganda hatte Raschhofer 1937 durch die Zusammenstellung einer strategisch wichtigen Dokumentation gelegt: Die tschechoslowakischen Denkschriften für die Friedenskonferenz von Paris 1919/20, ein Band, in dem die elf Denkschriften der tschechoslowakischen Delegation zusammengetragen waren, mit denen diese insbesondere ihre territorialen Forderungen nach Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs formuliert hatte.[25] Auch wenn die Denkschriften, wie Johann Wolfgang Brügel anmerkte, „überhaupt nicht geheim“ waren und kurz nach 1919 „bei Altpapierhändlern erstanden werden“ konnten[26] – und im übrigen von Raschhofer auch auf genau diesem Weg zufällig erworben worden waren – nutze die NS-Propaganda die Denkschriften im Rahmen der Kampagne zur Ausschaltung des „demokratischen Bollwerks“ (Brügel) Tschechoslowakei. Hierbei ging es insbesondere um das Mémoire No. 3, das sich mit der deutschen Minderheit in Böhmen befasste und – obgleich es bereits 1920 in einer deutschsprachigen Zeitschrift in Prag veröffentlicht worden war[27] – zur skandalträchtigen Inszenierung der These diente, die Tschechoslowakei betreibe im Geheimen eine minderheitenfeindliche Politik.

Raschhofers beratende Tätigkeit für das NS-Regime beschränkte sich jedoch nicht nur auf öffentliche Arbeiten, sondern umfasste auch geheimdienstliche Tätigkeiten. Spätestens seit 1941 unternahm Raschhofer regelmäßig Reisen in die Slowakei und verfasste politische Lageberichte und personenbezogene Stellungnahmen für Karl Hermann Frank und den deutschen Gesandten in der Slowakei, Hanns Ludin.[28] Im Herbst 1944 war Raschhofer dann im Auftrag von Frank auch an der Niederschlagung des bewaffneten Nationalaufstandes im NS-Marionettenstaat Slowakei als „politischer Berater“ des Generals der Waffen-SS Obergruppenführer Hermann Höfle beteiligt.[29] Unter der Kommandoführung von SS-Untersturmführer Adolf Leitgeb nahm Raschhofer dabei auch an einem „propagandistischen Einsatz“ der Einsatzgruppe H in der Slowakei teil, die den Aufstand als „sowjetisch bestimmt“ herausstellten[30] und beteiligte sich 1942/43 am Sonderverband Bergmann unter Führung von Theodor Oberländer als dessen persönlicher Berater.[31]

Bemerkenswert ist, dass Raschhofers Treue zum NS-Regime bis zuletzt Bestand hatte: So hatte er noch einen Aufsatz unter dem Titel Europäischer Nationalismus für das zu Ehren von Hitlers Geburtstag im Jahr 1945 geplante März/April-Heft der Zeitschrift Böhmen und Mähren verfasst, in dem er sich auch explizit positiv auf die „Neujahrsbotschaft des Führers“ bezog.[32]

Sein wissenschaftlicher Wiederaufstieg begann im Jahr 1952, als er Professor an der Universität Kiel wurde. Von dort aus ging er Ende 1955 als ordentlicher Professor (die Ernennung erfolgte nach einer kurzen Lehrstuhlvertretung im Januar 1957)[33] an die Universität Würzburg, zunächst für Kirchenrecht, Völkerrecht und Rechtsphilosophie später dann für „Staats- und Völkerrecht, insbesondere Minderheiten- und Nationalitätenrecht, Recht der internationalen Organisationen und Verfassungsgeschichte“.[34] Seine wissenschaftliche und politische Nachkriegskarriere wurde nie durch ein Ermittlungsverfahren gestört, obgleich er während seiner Tätigkeit an der Universität Würzburg von Studierendenseite wegen seiner NS-Aktivitäten öffentlich scharf kritisiert wurde.[35]

***

Bei dem Beitrag handelt es sich um eine stark gekürzte Fassung von Samuel Salzborn: Zwischen Volksgruppentheorie, Völkerrechtslehre und Volkstumskampf. Hermann Raschhofer als Vordenker eines völkischen Minderheitenrechts, in: Sozial.Geschichte, 21 (2006) 3, S. 29–52. Siehe zur historischen und theoretischen Einordnung insgesamt: Samuel Salzborn, Ethnisierung der Politik. Theorie und Geschichte des Volksgruppenrechts in Europa, Frankfurt a.M./New York 2005.

[1] Zusammengestellt aus: Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf, undatiert; Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf, 18. Juli 1939; „Stammblatt“ der Akte, undatiert (handschriftliche Ergänzungen bis Ende 1940), Bundesarchiv Berlin Dahlwitz-Hoppegarten (im Folgenden: BArchBD-H), ZB/2 1923, Akte 4.

[2] Foto: Manfred Abelein, Otto Kimminich (Hrsg.), Studien zum Staats- und Völkerrecht. Festschrift für Hermann Raschhofer zum 70. Geburtstag am 26. Juli 1975, Kallmünz: Verlag Michael Laßleben 1977.

[3] Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf, undatiert (Fn. 1).

[4] Vgl. Scheuner/Schumann/Schulin, Sachbericht in Sachen des Prof. Dr. J. W. Mannhardt, undatiert (ca. Juni 1955), Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg (im Folgenden HSTM), Best. 307d Acc. 1967/11, Nr. 385.

[5] Vgl. Max Hildebert Boehm, Bestätigung des Instituts für Grenz- und Auslandstudien e.V. in Berlin-Steglitz/Geschäftsstelle Lüneburg, datiert 25. November 1957, Universitätsarchiv Würzburg (im Folgenden: UAW), ARS R 29, Nr. II.

[6] Vgl. Max Hildebert Boehm, Das eigenständige Volk. Volkstheoretischen Grundlagen der Ethnopolitik und Geisteswissenschaften, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1932, 36-37; Hermann Raschhofer, Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff. Sonderdruck aus 25 Jahre Kaiser Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, Berlin: Springer 1937, 1, Fn. 1.

[7] Vgl. Ulrich Prehn, Max Hildebert Boehm. Radikales Ordnungsdenken vom Ersten Weltkrieg bis in die Bundesrepublik, Göttingen: Wallstein 2013.

[8] Bild: Wikimedia Commons.

[9] Hermann Raschhofer, Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts, Stuttgart: Enke 1931; Alle folgenden, im Text lediglich mit Seitenzahlen belegten Zitate beziehen sich auf diese Quelle.

[10] Vgl. Ingo Hueck, Die deutsche Völkerrechtswissenschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Das Berliner Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, das Hamburger Institut für Auswärtige Politik und das Kieler Institut für Internationales Recht, in: Doris Kaufmann (Hrsg.), Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven der Forschung, Bd. 2, Göttingen: Wallstein 2000, 490-527, 502, 511, 519.

[11] Hermann Raschhofer, Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff (Fn. 6), 16, 20; Alle folgenden, im Text lediglich mit Seitenzahlen belegten Zitate beziehen sich auf diese Quelle.

[12] Hermann Raschhofer, Der politische Volksbegriff im modernen Italien, Berlin: Volk und Reich 1936..

[13] Vgl. Hueck (Fn. 10), 518.

[14] Vgl. Schreiben von Hermann Raschhofer an Karl Herrmann Frank, datiert 21. September 1941, Národní archiv/Státní ústřední archiv Praha [Nationalarchiv/ehem. Staatliches Zentralarchiv] (im Folgenden NA/SÚA), NSM-AMV 110, Nr. 22, Sig. 110-4/155.

[15] Foto: BArch, Bild 146-1972-039-26.

[16] Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf, undatiert (Fn.1).

[17] Vgl. Hermann Raschhofer, Zum Gegenstandsbereich der Volkstheorie, Deutsche Arbeit, 32 (1932), 308.

[18] Vgl. Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf, undatiert; Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf, 18. Juli 1939; „Stammblatt“ der Akte (Fn.1).

[19] Vgl. Schreiben des Sicherheitsdienstes des Reichsführer-SS/SD-Leitabschnitt Prag an Gies, Deutsches Staatsministerium für Böhmen und Mähren, datiert 21. November 1944, Archiv Ministerstva Vnitra Praha [Archiv des Tschechischen Innenministeriums] (im Folgenden: MVČR), Z-10-P-72.

[20] Vgl. Peter K. Steck, Zwischen Volk und Staat. Das Völkerrechtssubjekt in der deutschen Völkerrechtslehre (1933–1941), Baden-Baden: Nomos 2003, 123.

[21] Vgl. Karel Fremund, Z činnosti poradců nacistické okupační moci (Výběr dokumentů), Prag: Archivní správa Ministerstva vnitra Roč 1966, 24-25, 40-41.

[22] Vgl. Václav Král (Hrsg.), Die Deutschen in der Tschechoslowakei 1933–1947. Dokumentensammlung, Prag: Nak. Československé akademie věd 1964, 454.

[23] Vgl. Schreiben des NS-Dozentenbund/Der Reichsdozentenbundsführer an Wacker, Reichserziehungsministerium, datiert 21. Juni 1938, BArchBD-H, ZB/2 1923, Akte 4.

[24] 1933 erklärte Raschhofer: „Im Nationalsozialismus gruppiert sich ein politischer Kader, der mit Bewußtsein vom Ganzen der geschichtlich existenten deutschen Nation her denkt und daraus seine Totalitätsansprüche rechtfertigt.“, Zitiert nach: Walter Heynowski/Gerhard Scheumann, Der Mann ohne Vergangenheit, in: Der Präsident im Exil und Der Mann ohne Vergangenheit sowie ein nachdenklicher Bericht über Die Schlacht am Killesberg, Berlin: Verlag der Nation 1969, 124.

[25] Vgl. Hermann Raschhofer, Die tschechoslowakischen Denkschriften für die Friedenskonferenz von Paris 1919/1920, Berlin: Heymanns 1937, 2. ergänzte Aufl. 1938.

[26] Vgl. Johann Wolfgang Brügel, Tschechen und Deutsche 1918–1938, München: Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung 1967, 87.

[27] Vgl. Elizabeth Wiskemann, Czechs & Germans. A study of the struggle in the historic provinces of Bohemia and Moravia, 2. Aufl., London: Macmillan 1967.

[28] Vgl. die entsprechenden Berichte in: NA/SÚA ÚŘP-AMV 114 Nr. 14 Sig. 114-3/18

[29] Vgl. Johann Wolfgang Brügel (Fn. 26), 96-97.

[30] Vgl. Chef der Einsatzgruppe H der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD, Bescheinigung, 23. Oktober 1944; Adolf Leitgeb, Kommandobericht, 29. Oktober 1944, MVČR 302-64-10.

[31] Vgl. Albert Jeloschek et al., Freiwillige vom Kaukasus. Georgier, Armenier, Aserbaidschaner, Tschetschenen u.a. auf deutscher Seite – Der „Sonderverband Bergmann“ und sein Gründer Theodor Oberländer, Graz: Stocker 2003, 139, 161; Philipp-Christian Wachs, Der Fall Theodor Oberländer (1905–1998). Ein Lehrstück deutscher Geschichte, Frankfurt a.M.: Campus Verlag 2000, 104.

[32] Vgl. Hermann Raschhofer, Europäischer Nationalismus (Korrekturfahne); Schreiben von Hess, Hauptschriftleiter „Böhmen und Mähren“ an Gies, Deutsches Staatsministerium für Böhmen und Mähren, datiert 16. März 1945, NA/SÚA, NSM-AMV 110, Nr. 106, Sig. 110-12/134.

[33] Vgl. Ernennungsurkunde des Freistaates Bayern, 24. Januar 1957, UAW, ARS R 29, Nr. II.

[34] Vgl. Schreiben des Bayerisches Staatsministeriums für Unterricht und Kultus an das Rektorat der Universität Würzburg, datiert 26. März 1962, UAW, ARS R 29, Nr. II.

[35] Vgl. Süddeutsche Zeitung, 27. Januar 1970.

In the German-speaking world after the First World War, traditional approaches to the protection of religious minorities and the domestic nationality policy of Austria-Hungary increasingly gave way to the development of a minority policy under international law. Against the backdrop of the European reorganisation based on the Treaties of Paris, individual legal protection against discrimination, the main features of which had already been developed at the time, were replaced by a system of collective privileges based on descend and race, i.e. völkisch in nature. A decisive role in the theoretical development of the ‘modern’ law of nationality and of ethnic groups (Volksgruppenrecht) was played by Hermann Raschhofer (1905-1979), especially with his works on the “Main Problems of Nationality Law “ (Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts, 1931)[1] and “Nationality as Essence and Legal Concept” (Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff, 1936/37), which are still influential in völkisch theories of international law today.

Early Life and Education

Raschhofer was born on 26 July 1905 in Ried im Innkreis (Upper Austria). He studied law and political science in Marburg, Vienna and Innsbruck, passed his first state examination in law in 1925 and his second in 1928. He obtained his doctorate in political science in Innsbruck in 1927 and his doctorate in law in 1928. From April 1928 to March 1930, he was an assistant at the “Institute for the Studies of Borders and Foreign Affairs” (“Grenz- und Auslandsstudien”) in Berlin-Steglitz, then an assistant at the Faculty of Law at the University of Tübingen. From autumn 1931 to the end of 1933, Raschhofer was a fellow of the Rockefeller Foundation in France (Paris) and Italy (Turin).[2]

Hermann Raschhofer, 1975[3]

Raschhofer’s academic interests, which – as he himself wrote – ‘developed in connection with practical work in the borderlands, quickly focussed on questions of nationality law.’[4] His political outlook on scientific practice was strongly influenced by his choice of the university of Marburg and by Johann Wilhelm Mannhardt, who taught there. Mannhardt held the professorship for “Germanness Across Borders and in the Exterior” (“Grenz- und Auslanddeutschtum”), which had been created especially for him, at the in 1919 newly established “Institute for Germanness Across Borders and in the Exterior” within the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Marburg and was initially the managing director and later also the scientific director of this institute.[5] Raschhofer was also influenced by his involvement with the work of Max Hildebert Boehm, with whom he also built up a personal relationship during his time as a research assistant at the “Institute for the Studies of Borders and Foreign Affairs” in Berlin-Steglitz at the end of the 1920s.[6] In his academic work on nationality law, Raschhofer adopted Boehm’s diction, according to which ‘a nationality [… must] arise wherever the non-coincidence of borders between nations and between peoples gives rise to ethnically conditioned sub-regions that have gained or are striving to gain a formation of some kind through contact with the state, i.e. in the element of politics.’[7] He shared Boehm’s euphoric commitment to the theory of an ‘independent people’, which was the most important theoretical assumption for the European ethnic group policy (“Volksgruppenpolitik”) of the Weimar period.[8]

Raschhofer and Nationality Law

Map pf nationalities in Austria-Hungary (1911), The Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1911.[9]

Raschhofer’s first major academic work, entitled Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts,[10] for which he was awarded first prize in a prize competition on minority law by the German Academy (Munich) in 1929, already pursued this goal, albeit in a more moderate linguistic style. In this study, Raschhofer analysed positive international minority law and contrasted it with the ‘institutions of nationality law’ (5), i.e. the legal instruments that the proponents of nationality law wanted to replace liberal-democratic minority law with in domestic and international law. The focus was always to be on the ‘rights of the nationality as personality of the people’, with the aim of creating a ‘constitution as a body of public law’ (76). Raschhofer thereby explicitly opposed what he called the ‘Greater Paris Minority Protection Treaties’, which he criticised to the effect that ‘the nationalities under minority law must live under the legal status of national individuals conceived of as atomised’ without being recognised as ‘organic personalities’ (76f.) and without being ‘entitled to their own rights as legal personalities’ (78):

‘Nationality is […] not a quality that occurs by chance in some citizens per se and brings them together, so to say, subsequently, like, for example, the members of an association for the representation of any interests come together by association of former strangers; it is not sum, but totality.’ (77)

In this understanding, we can only speak of nationality when – as Raschhofer wrote – ‘its members appear group-like and organic, namely as historically-culturally positively qualifiable ethnic groups.’ (77)

The nationality right to be striven for would protect ‘well-acquired rights’ and irrevocably demand the connection between ‘land and history’ (77). The ‘essence of nationality’ postulated by Raschhofer required the legal possibility ‘to be one’s own master in one’s own area, i.e. autonomy’ (154).

In this, his first major draft on the subject of nationality law, Raschhofer developed a concept of nationality as a ‘totality’ (77) with ‘sacred rights’ (156), which he explicitly distinguished from the concept of minority. Since Raschhofer assumed an essentialist or primordial concept of ethnicity, he considered peoples, ethnic groups, and nationalities as supernatural beings whose existence does not require further proof and whose attestable differences he interpreted not as having arisen historically and thus being changeable and abolishable, but as substantial ethnic, cultural, and also ‘racial’ differences. Ethnicity, thus declared a fact, in turn formed the basis for Raschhofer’s model of nationality law. In his view, nationality law should always be oriented towards the collective as its legal subject and endeavour to create exclusive privileges for nationalities vis-à-vis the rest of the population. Here, Raschhofer’s fundamental opposition to both the republican nation state and the liberal minority policy of the League of Nations was already evident – while the republican nation state was conceived precisely as a unity of its citizens with equal rights, the minority protection treaties concluded after the end of the First World War had been created with the aim of individual protection against discrimination.

Raschhoefer at the KWI

Die geisteswissenschaftlichen Festbeiträge: Raschhofer, Graf Mandelsloh und KWI-Direktor Viktor Bruns vertreten das KWI für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht

With the publication of Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts Raschhofer had established his academic profile as a scholar of nationality law. After his teaching and research activities at the Berlin “Institute for the Studies of Borders and Foreign Affairs”, in Tübingen, Paris and Turin, the holder of two doctorates finally came to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (KWI) in Berlin via Erich Kaufmann. Raschhofer became a research fellow at the KWI in January 1934 and remained there until October 1937. His time at the KWI was very important for him, as he was able to build up a lasting reputation as an expert on nationality issues. In 1936, for example, he wrote the Institute’s contribution on the topic of “Nationality as Essence and Legal Concept” (Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff) in the edition commemorating the Kaiser Wilhelm Society’s 25th anniversary, which, in addition to a great honour for him, also meant the further popularisation of his theses.[11]

This essay, which was also published separately in book form, is particularly noteworthy because Raschhofer sharpens his theses from Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts and clearly expresses the völkisch foundation of his theory of nationality law. Raschhofer now understands nationality as a ‘völkisch group that distinguishes the individual as a member of a sub-group from the other nationals’, indeed a ‘völkisch essence’.[12] In his view, the individual’s ties to this collective are to be regarded as ‘superior, objective and at the same time formative’ (20), while nationality is characterised by a ‘natural character’, namely ‘the element of permanence, the resting in the prehistoric’. (21)

Nationality, according to Raschhofer is a ‘partial whole’ belonging to a community of kind’, ‘part’ of a ‘blood-based community of kind’ (44), which is why the commitment to the Volksgemeinschaft (“community of the people”) and nationality does, in his view, not establish anything new, but merely emphasises ‘in terms of will’ (44) what is already supposedly objectively present:

‘In the realm of the Völkisch, there is only an affirmation of one’s own sole or predominant kind, and the abnormality of the theoretically and practically possible case of rejection of one’s own kind is sufficiently described with the condemning word degeneration [Entartung].

There is therefore by nature an objectively defined circle of those who can profess to belong to a people, to a nationality as a community of kind. If the Nuremberg Laws have set such a limitation by finally definitively separating those who are of a foreign kind and those who are of a related kind, whereby the Jewish half-breeds, in whom the German-blooded predominates, were allowed to merge into Germanness, then only hopelessly liberal know-it-alls can characterise this as a procedure detrimental to the interests of the ethnic groups.’ (45)

The confrontation with the republican nation state, already alluded to in his work Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts, is openly articulated in Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff. The republican nation state is now regarded by Raschhofer as a ‘coercive apparatus’; he devalues citizenship in contrast to membership in nationality, since the former ‘need not represent a primary, sociologically natural entity’ (16), whereas the latter is characterised by its ‘originality and independence as a social entity, as a real group’ and thus differs ‘essentially from the abstract sum of citizens’ (17) – which also leads Raschhofer to differentiate between a state as a ‘legal community’ and a ‘community of the people [Volksgemeinschaft]’ (17).

While Raschhofer’s arguments in Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts are still orientated towards an almost equal status of the state and the people, even if the nationalities should be granted more rights, the non-völkisch state in Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff completely takes on the negative role of having to justify itself to the nationalities. Regardless of whether a legal system recognises or denies the existence of nationalities, according to Raschhofer, this cannot be regarded as an objective sociological decision, as the legal view of the subject cannot entail any sociological value:

‘The “definition of the people, of nationality [from the perspective of the legal concept of nationality]”, can never answer the question of its essence. It must encompass the multi-dimensional, entangled, foreground and background layers, reflective and dreaming existence, blood and history, the structure of the concrete nationality held together by interests, habit, enthusiasm and sacrifice, and reduce it to the one-dimensionality of a legal association based on individual acts of will.’ (43)

The republican nation state is to be deprived de facto of the possibility of non-recognition of nationalities in the völkisch-collective sense, since a legal system that does not recognise this alleged factuality of the Völkisch is considered illegitimate in its actions. The legal method is thus reversed, and the legal positivist approach is replaced by a natural law perspective in the pre-Enlightenment tradition based on the principle that the supposedly supernatural and consistent law of the völkisch ethnic groups precedes positive law.

During his time at the KWI, Raschhofer not only honed his profile as a nationality law expert loyal to the regime, but also as a pioneer in this issue, as his writings on nationality law are among the first ever to merge a legal perspective (of international law) with a völkisch perspective – Raschhofer himself describes this as ‘sociological’ – with the aim of formulating a homogeneous model of a ‘modern’ law of ethnic groups and nationalities as a binding blueprint for Europe’s legal order. Moreover, his time at the KWI coincided with his habilitation in February 1937 (and his appointment as Dr jur. habil. in July 1937) at the University of Berlin under the international law expert Prof. Dr Viktor Bruns, who was also the director of the KWI. Raschhofer habilitated with the book “Der politische Volksbegriff im modernen Italien” (“The political concept of the people in modern Italy”).[13] His academic career was thus successfully continued and immediately after his habilitation, Raschhofer also took up a substitute position in Göttingen[14], which lasted until 1939 and also received an offer from the Foreign Office to ‘join one of the Reich’s European embassies as a press attaché’. [15]

Raschhofer as a National Socialist Lawyer and Activist

Reinhard Heydrich, Deputy Reichsprotekor in Bohemia and Moravia with Karl Hermann Frank at Prague Castle in 1941[16]

Parallel to his academic career, Raschhofer worked on the practical implementation of his maxims: ‘In the last few years, theoretical studies were joined by practical advisory work for German ethnic groups abroad in matters of positive minority law and constitutional law,’ he summarised his activities in retrospect in the mid-1930s.[17] And in a discussion of Boehm’s work on the ‘independent people’, Raschhofer wrote that the subject of the ‘people’ presented itself ‘simultaneously as an object of endeavours of scientific nature and of sociological inquiry based on the theory of the people, as well as a subject and object of practical politics’,[18] which undoubtedly also reflected his own integration of völkisch theory formation and völkisch political practice. Fittingly, Raschhofer was a member of the illegal Austrian NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei Österreichs, “National Socialist German Workers’ Party of Austria”), the VDA (Verein für Deutsche Kulturbeziehungen im Ausland, “Association for German Cultural Relations Abroad”), the National Socialist Association of Lawyers (“Juristenbund”) and the National Socialist Association of University Teachers (“Dozentenbund”). At the beginning of the 1930s, he began his work as a legal policy advisor for the illegal Austrian NSDAP and for the Sudetendeutsche Partei (“Sudeten German Party”, SdP).[19] His proximity to the politics of the Sudeten Germans, in particular resulting from his close contact with Konrad Henlein and Karl Hermann Frank, laid the foundation for his appointment to Prague: in 1940, Raschhofer first took on an associate and later a full professorship at the German University of Prague, where he headed the Institut für Völker- und Reichsrecht (“International Law and Law of the Reich”) and was also to become Dean of the Faculty of Law in 1944, but declined because he had ‘too many other assignments’.[20] Raschhofer’s appointment to the German University of Prague was at the personal request of Karl Hermann Frank, whose legal advisor Raschhofer became and with whom he was closely connected through personal friendship.[21] Frank had already campaigned for Raschhofer’s appointment to Prague in April 1939, as he had been advising both him and Konrad Henlein on political and academic matters since 1934 and was to act as an advisor on special legal issues in the Protectorate in future.[22] According to Frank, Raschhofer had ‘made valuable contributions not only to the treatment of enemy propaganda, but also to the fight against the Czech conception of the state and history.’[23] Generally, Raschhofer’s closeness to the Nazi regime was undoubted. In 1938, the leader of the Reichsdozentenbund certified that ‘politically speaking’ he was a ‘resolute ethnic German [Volksdeutscher]’ and that he was also ‘in favour of National Socialist ideas in domestic politics’.[24] Raschhofer had welcomed the Nazi takeover in 1933 as well as the later annexation of Austria and the Sudeten territories to the German Reich.[25]

Raschhofer in the ‘Contributions on Comparative Public Law and International Law’ (Beiträge zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht)

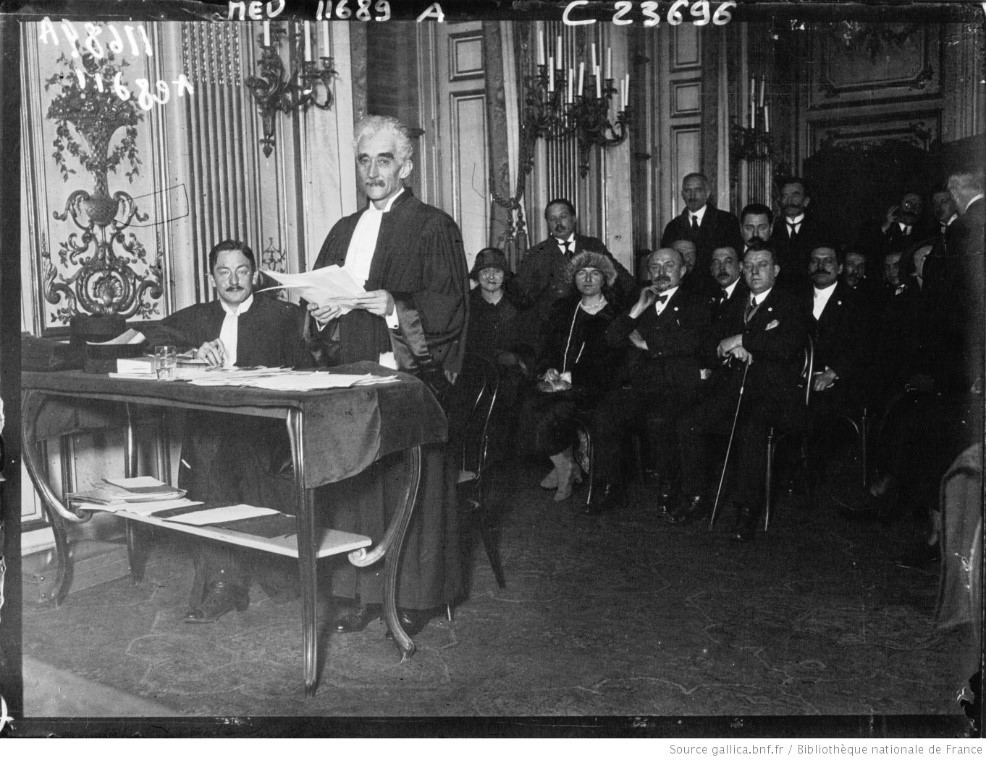

Raschhofer had helped lay the foundation for the destabilisation of Czechoslovakia by Nazi propaganda in 1937 by compiling a strategically important documentation: Die tschechoslowakischen Denkschriften für die Friedenskonferenz von Paris 1919/20 (“The Czechoslovak memoranda for the Paris Peace Conference of 1919/20”) , a volume in which the eleven memoranda of the Czechoslovak delegation were compiled, in which they had formulated their territorial demands after the end of the First World War in particular.[26] Even though the memoranda, as Johann Wolfgang Brügel noted, were ‘not at all secret’ and could be ‘purchased from waste paper dealers’ shortly after 1919[27] – and incidentally had also been acquired by Raschhofer by chance in precisely this way – Nazi propaganda used the memoranda as part of the campaign to eliminate the ‘democratic bulwark’ (Brügel) of Czechoslovakia. The focus laid on Mémoire No. 3, which dealt with the German minority in Bohemia and – although it had already been published in a German-language magazine in Prague in 1920[28] – served to orchestrate a scandal based on the idea that Czechoslovakia was secretly pursuing a policy hostile to minorities.

Raschhofer’s advisory activities for the Nazi regime were however not limited to public work, but also included intelligence activities. From 1941 at the latest, Raschhofer regularly travelled to Slovakia to write reports on the political situation as well as on specific persons for Karl Hermann Frank and the German Ambassador to Slovakia, Hanns Ludin.[29] In autumn 1944, Raschhofer was also involved on behalf of Frank in the suppression of the armed national uprising in the Nazi puppet state of Slovakia as a ‘political advisor’ to SS general Hermann Höfle.[30] Under the command of SS commander Adolf Leitgeb, Raschhofer also took part in a ‘propaganda operation’ of Einsatzgruppe H in Slovakia, which exposed the uprising as ‘Soviet-determined’[31] and participated in the Bergmann Battalion under the leadership of Theodor Oberländer as his personal advisor in 1942/43.[32]

It is remarkable that Raschhofer’s loyalty to the Nazi regime lasted until the end: he had written an essay entitled “European Nationalism” (“Europäischer Nationalismus”) for the fourthcoming March/April issue of the journal “Böhmen und Mähren”, planned in honour of Hitler’s birthday in 1945, in which he also explicitly commended the ‘Führer’s New Year’s message’.[33] His academic resurgence began in 1952, when he became a professor at the University of Kiel. From there, he moved to the University of Würzburg at the end of 1955 as a full professor (his appointment followed a brief period as a substitute professor in January 1957),[34] initially for canon law, international law and philosophy of law, and later for ‘constitutional and international law, in particular minority and nationality law, the law of international organisations and constitutional history’.[35] His post-war academic and political career was never disrupted by any investigation, although, during his time at the University of Würzburg, he was publicly criticised by students for his Nazi activities.[36]

***

This contribution is an abridged version of: Samuel Salzborn, Zwischen Volksgruppentheorie, Völkerrechtslehre und Volkstumskampf. Hermann Raschhofer als Vordenker eines völkischen Minderheitenrechts, in: Sozial.Geschichte 21 (2006), 29–52; for an overall historical and theoretical contextualisation, see: Samuel Salzborn, Ethnisierung der Politik. Theorie und Geschichte des Volksgruppenrechts in Europa, Frankfurt a.M.: Campus 2005.

Translation from the German original: Sarah Gebel

[1] This and all following titles of works as well as names of institutions have been translated by the editor, where necessary.

[2] Compiled from: Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf [curriculum vitae], undated; Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf [curriculum vitae], dated 18 July 1939; „master sheet“ of the file, undated (handwritten annotations up to the end of 1940), Bundesarchiv Berlin Dahlwitz-Hoppegarten (in the following: BArchBD-H), ZB/2 1923, file 4.

[3] Foto: Manfred Abelein, Otto Kimminich (Hrsg.), Studien zum Staats- und Völkerrecht. Festschrift für Hermann Raschhofer zum 70. Geburtstag am 26. Juli 1975, Kallmünz: Verlag Michael Laßleben 1977.

[4] Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf, undated (fn. 2); this and all following quotations have been translated by the editor.

[5] Cf. Scheuner/Schumann/Schulin, Sachbericht in Sachen des Prof. Dr. J. W. Mannhardt, undated (ca. June 1955), Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg (in the following: HSTM), Best. 307d Acc. 1967/11, Nr. 385.

[6] Cf. Max Hildebert Boehm, Bestätigung des Instituts für Grenz- und Auslandstudien e.V. in Berlin-Steglitz/Geschäftsstelle Lüneburg, dated 25 November 1957, Universitätsarchiv Würzburg (in the following: UAW), ARS R 29, Nr. II.

[7] Cf. Cf. Max Hildebert Boehm, Das eigenständige Volk. Volkstheoretischen Grundlagen der Ethnopolitik und Geisteswissenschaften, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1932, 36-37; Hermann Raschhofer, Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff. Sonderdruck aus 25 Jahre Kaiser Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, Berlin: Springer 1937, 1, fn. 1.

[8] Cf. Ulrich Prehn, Max Hildebert Boehm. Radikales Ordnungsdenken vom Ersten Weltkrieg bis in die Bundesrepublik, Göttingen: Wallstein 2013.

[9] Bild: Wikimedia Commons.

[10] Hermann Raschhofer, Hauptprobleme des Nationalitätenrechts, Stuttgart: Enke 1931; all following citations referenced only by page numbers in the text are from this source.

[11] Cf. Ingo Hueck, Die deutsche Völkerrechtswissenschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Das Berliner Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, das Hamburger Institut für Auswärtige Politik und das Kieler Institut für Internationales Recht, in: Doris Kaufmann (ed.), Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven der Forschung, Vol. 2, Göttingen: Wallstein 2000, 490-527, 502, 511, 519.

[12] Hermann Raschhofer, Nationalität als Wesen und Rechtsbegriff (fn. 7), 16, 20; all following citations referenced only by page numbers in the text are from this source.

[13] Hermann Raschhofer, Der politische Volksbegriff im modernen Italien, Berlin: Volk und Reich 1936.

[14] Cf. Hueck (fn. 11), 518.

[15] Cf. Letter from Hermann Raschhofer to Karl Herrmann Frank, dated 21 September 1941, Národní archiv/Státní ústřední archiv Praha [National Archive] (in the following: NA/SÚA), NSM-AMV 110, Nr. 22, Sig. 110-4/155.

[16] Photo: BArch, Bild 146-1972-039-26.

[17] Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf, undated (fn. 2).

[18] Cf. Hermann Raschhofer, Zum Gegenstandsbereich der Volkstheorie, Deutsche Arbeit, 32 (1932), 308.

[19] Cf. Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf, undated; Hermann Raschhofer, Lebenslauf, dated 18 July 1939; “master sheet“ of the file (fn. 2).

[20] Cf. Letter from the Sicherheitsdienst of the SS Leader/ District of Prague [Sicherheitsdienstes des Reichsführer-SS/SD-Leitabschnitt Prag] to Gies, German Ministry for Bohemia and Moravia [Deutsches Staatsministerium für Böhmen und Mähren], dated 21 November 1944, Archiv Ministerstva Vnitra Praha [Archive of the Czech Ministry of the Interior] (in the following: MVČR), Z-10-P-72.

[21] Cf. Peter K. Steck, Zwischen Volk und Staat. Das Völkerrechtssubjekt in der deutschen Völkerrechtslehre (1933–1941), Baden-Baden: Nomos 2003, 123.

[22] Cf. Karel Fremund, Z činnosti poradců nacistické okupační moci (Výběr dokumentů), Prague: Archivní správa Ministerstva vnitra Roč 1966, 24-25, 40-41.

[23] Cf. Václav Král (ed.), Die Deutschen in der Tschechoslowakei 1933–1947. Dokumentensammlung, Prague: Nak. Československé akademie věd 1964, 454.

[24] Cf. Letter from the National Socialist Association of University Teachers/ Führer of the Association [NS-Dozentenbund/Der Reichsdozentenbundsführer] to Wacker, Federal Ministy of Education [Reichserziehungsministerium], dated 21 June 1938, BArchBD-H, ZB/2 1923, file 4.

[25] 1933 Raschhofer declared: “In National Socialism a political cadre is forming, which is conscious of the whole of the historical existence of the German nation and deriving its claim to totality from that”, cited after: Walter Heynowski/Gerhard Scheumann, Der Mann ohne Vergangenheit, in: Der Präsident im Exil und Der Mann ohne Vergangenheit sowie ein nachdenklicher Bericht über Die Schlacht am Killesberg, Berlin: Verlag der Nation 1969, 124.

[26] Cf. Hermann Raschhofer, Die tschechoslowakischen Denkschriften für die Friedenskonferenz von Paris 1919/1920, Berlin: Heymanns 1937, 2nd enlarged ed. 1938.

[27] Cf. Johann Wolfgang Brügel, Tschechen und Deutsche 1918–1938, Munich: Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung 1967, 87.

[28] Cf. Elizabeth Wiskemann, Czechs & Germans. A study of the struggle in the historic provinces of Bohemia and Moravia, 2nd ed., London: Macmillan 1967.

[29] Cf. The corresponding reports in: NA/SÚA ÚŘP-AMV 114 Nr. 14 Sig. 114-3/18.

[30] Johann Wolfgang Brügel (fn. 27), 96-97.

[31] Cf. Leader of the Einsatzgrupe H of the Sicherheitspolizei and the Sicherheitsdienst [Chef der Einsatzgruppe H der Sicherheitspolizei und des Sicherheitsdienst], confirmation, 23 October 1944; Adolf Leitgeb, commando report, 29 October 1944, MVČR 302-64-10.

[32] Cf. Albert Jeloschek et al., Freiwillige vom Kaukasus. Georgier, Armenier, Aserbaidschaner, Tschetschenen u.a. auf deutscher Seite – Der „Sonderverband Bergmann“ und sein Gründer Theodor Oberländer, Graz: Stocker 2003, 139, 161; Philipp-Christian Wachs, Der Fall Theodor Oberländer (1905–1998). Ein Lehrstück deutscher Geschichte, Frankfurt a.M.: Campus Verlag 2000, 104.

[33] Cf. Hermann Raschhofer, Europäischer Nationalismus (galley proof); Letter from Hess, Hauptschriftleiter „Böhmen und Mähren“ to Gies, German Ministry for Bohemia and Moravia [Deutsches Staatsministerium für Böhmen und Mähren], dated 16 March 1945, NA/SÚA, NSM-AMV 110, no. 106, sig. 110-12/134.

[34] Cf. Certificate of appointment issued by the state of Bavaria, 24 January 1957, UAW, ARS R 29, Nr. II.

[35] Cf. Letter from the Bavarian Ministry for Education and Culture [Bayerisches Staatsministeriums für Unterricht und Kultus] to the rectorate of Würzburg University, dated 26 March 1962, UAW, ARS R 29, Nr. II.

[36] Cf. Süddeutsche Zeitung, 27 January 1970.