Deutsch

Die Kapitulationen am Ende des Ersten und des Zweiten Weltkrieg gelten als Niederlagen Deutschlands, nicht nur seiner Armee oder Regierung. Sie bilden tiefe gesellschaftliche Zäsuren und prägen den deutschen Weg bis heute, auch den des Instituts für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht. Wir verstehen diese Kapitulationen als critical junctures[1] und zeigen, dass sie einen roten Faden bilden, der viele Positionierungen des Instituts verbindet und seine Forschung durchzieht. Eine Kontrastfolie bildet das Genfer Institut de hautes études internationales, das ab 1927 die neue Ordnung aus der Siegerperspektive begleitete.[2]

Der rote Faden der Niederlagen dominiert das Institut der Zwischenkriegszeit und der frühen Bundesrepublik, erschließt aber auch viele Aspekte der jüngeren Institutsgeschichte. Er findet sich in den Studien zur deutschen Einheit und zum Zusammenwachsen Europas nach dem Fall des Eisernen Vorhangs, zum Völkerrecht als Werteordnung, zum globalen Konstitutionalismus. Gewiss verliert er an Deutungskraft mit der zeitlichen Distanz und mit der personellen Internationalisierung des MPIL. Dieser Beitrag zeigt den roten Faden anhand prägender Positionierungen des Instituts in der Weimarer Republik und seiner Neupositionierung in der jungen Bundesrepublik.

Wohlgemerkt: Der rote Faden besteht allein aus der Deutung der Kapitulationen als prägende deutsche Niederlagen. Nur diese Deutung ist geradezu selbstverständlich, anders als Deutungen der Kriegsursachen, der Kriegsschuld, von Ausmaß und Einzigartigkeit deutscher Verbrechen. Es sei weiter betont, dass diese These nicht monokausal und nicht deterministisch ist.[3] Viele weitere Kräfte haben den Weg des Instituts mitgeprägt. Der rote Faden verläuft zudem alles andere als geradlinig: So zielte das Institut nach der ersten Niederlage auf eine Revision der völkerrechtlichen Nachkriegsordnung, nach der zweiten hingegen auf deren konsequente Entfaltung. Die Behauptung eines roten Fadens behauptet auch keinen Konsens in der Bewertung oder der Konsequenzen, die man zog. Viele Beiträge dieses Blogs zeigen einen bisweilen erstaunlichen Pluralismus, wie innerhalb des Instituts mit den Niederlagen umgegangen wurde. Unser roter Faden kann nur deshalb ein roter Faden sein, weil er vieles offen, ja strittig lässt. Auf den Punkt gebracht: Wir schreiben kein Narrativ.

Eine Verliererinstitution

Die Gründung des Instituts am 19. Dezember 1924 ist eine Folge der Kapitulation. Deutschland musste sich als Verlierer einer neuen internationalen Ordnung beugen und sich in ein von seinen Gegnern dominiertes System einordnen. Die Niederlage stellte das deutsche Völkerrecht, auch als wissenschaftliche Disziplin, vor unerhörte Herausforderungen. Nunmehr stand es allein, ohne eine große Armee an seiner Seite. Die Pariser Vorortverträge, zumal der von Versailles, gaben ihm schwerste Probleme auf, etwa die Gebietsabtrennungen, die Beschränkungen der Souveränität, enorme Reparationszahlungen, die Kriegsschuld, weltpolitische Isolation. Zudem litt das deutsche Völkerrecht an einem Mangel kompetenter Völkerrechtler, von Völkerrechtlerinnen ganz zu schweigen. Der Etatismus des Kaiserreichs hatte wenig Interesse am Völkerrecht gehabt, so dass die Disziplin über Jahrzehnte vernachlässigt worden war.

Die Gründung des Instituts reagierte auf diese Lage. So heißt es in der von dem Generalsekretär der KWG Friedrich Glum und die beiden Berliner Professoren Viktor Bruns und Heinrich Triepel verfasste Denkschrift zu seiner Gründung:

„Deutschland wird sich für Jahrzehnte die Pflege internationaler Beziehungen mehr denn je angelegen sein lassen müssen, um sich zu schützen gegen die unberechtigten Ansprüche seiner Kriegsgegner, um seinen Landsleuten in den abgetretenen Gebieten zu helfen und um sich aufs neue Geltung in der Welt zu verschaffen.“[4]

Das Institut begann als „Verlierer-Institution“. Das hatte Folgen, die aber ganz unterschiedlich ausfallen konnten, etwa als ein kritisches oder aber als ein emphatisches Völkerrechtsverständnis. Eine naheliegende Folge wäre ein Verständnis als ein Instrument der Starken zur Unterdrückung der Schwachen gewesen, ‚the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must‘. Das Institut entschied sich anders, klüger. Einem Land mit einer Wehrmacht von nur 100.000 Mann nutzt eher ein Völkerrechtsverständnis, wonach das Recht mehr ist als nur die Formalisierung von Macht. Der Interessenlage entspricht ein Verständnis als ein eigenständiges, gerade auch machthemmendes Ordnungssystem. So ist es kein Zufall, dass Bruns‘ Gründungsaufsatz der Institutszeitschrift die Autonomie des Völkerrechts beschwört, „Völkerrecht als Rechtsordnung“.

Diese Art der Verarbeitung der Niederlage durch das KWI war keineswegs zwangsläufig. Das zeigt der Vergleich mit dem 1922 von Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy gegründeten Hamburger „Institut für auswärtige Politik“ und insbesondere dem bereits 1914 ins Leben gerufenen Kieler „Institut für Internationales Recht“, das ab 1926 Walther Schücking leitete. Auch diese beiden Institute verarbeiteten die Niederlage, aber mit einem progressiveren Verständnis des Völkerrechts, das sich zur internationalen Ordnung und Völkerbund bekannte. Solche Bekenntnisse kennzeichneten nicht die Arbeit des KWI. Selbst ‚Völkerrecht als Rechtsordnung‘ erscheint mehr ein Mittel als ein Zweck. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg zeigte sich diese Offenheit des Umgangs mit der Niederlage sogar intern. Während Carl Bilfinger (1879-1958) als Wiedergründungsdirektor 1950 eine Friedensordnung im Gleichgewicht der Mächte nach dem überkommenen Muster des Wiener Kongresses empfahl, setzte sein Nachfolger Hermann Mosler (1912-2001) konsequent auf eine Westintegration, welche die bisherigen völkerrechtlichen Formen sprengte.

Konkrete Erfahrungen der Niederlagen

Das ausgebrannte Schloss 1946[5]

Die Prägekraft der Niederlagen sei anhand der Institutsangehörigen konkretisiert. Betrachtet man die Personalstruktur des KWI, so war sie „vergleichbar mit der am Auswärtigen Amt: Adlige Herkunft, bürgerliche Tradition und ein gewisser gesellschaftlicher Dünkel dominierten.“[6] Angesichts einer zumeist ausgeprägt nationalen Haltung empfanden viele die Niederlage als besonders schmerzlich. Das ist offensichtlich bei der Leitungsebene des Institutes um seinen Gründer Viktor Bruns (1884-1943), die die wissenschaftlichen Mitglieder bzw. Berater Rudolf Smend (1882-1975), Erich Kaufmann (1880-1972) sowie den zweiten Direktor und Cousin Viktor Bruns‘ Carl Bilfinger (1879-1958) umfasste. Dabei hatte lediglich Erich Kaufmann als mehrfach dekorierter Soldat am Krieg teilgenommen, den er in seiner berühmten, inzwischen berüchtigten Schrift über das „Wesen des Völkerrechts“ geradezu herbei gewünscht hatte.[7] Viktor Bruns und Heinrich Triepel gehörten zu den mehr als 3000 Professoren, die 1914 die nationalistische „Erklärung der Hochschullehrer des Deutschen Reiches“ unterzeichnet und den Krieg dann auch aktiv begleitet hatten.

Als Soldaten am Ersten Weltkrieg teilgenommen hatten nur wenige Institutsangehörige, wie Hermann Heller (1891-1933), Carlo Schmid (1896-1979) oder Friedrich Berber (1898-1984). Die meisten Referenten hatten den Krieg im Jugendalter und fernab der Front erlebt, so Joachim Dieter Bloch (1906-1945), Karl Bünger (1903-1997), Joachim von Elbe (1902-2000), Herbert Kier (1900-1973), Gerhard Leibholz (1901-1982), Hans-Joachim von Merkatz (1905-1982), Hermann Mosler (1912-2001), Hermann Raschhofer (1905-1979), Helmut Strebel (1911-1992), Ulrich Scheuner (1903-1981), Berthold von Stauffenberg (1905-1944) oder Wilhelm Wengler (1907-1995).[8] Die Angehörigen dieser „Kriegsjugendgeneration“, die ganz im Geiste des deutschen Nationalismus und der Kriegspropaganda aufgewachsen waren, zeichnete eine merkwürdige Verbitterung aus: Sie hatten die Kriegsteilnahme und somit die nationale Bewährung verpasst, was sie anderweitig zu kompensieren suchten.[9] Die Prägung durch Krieg und Niederlage tritt in autobiographischen Schriften von Institutsangehörigen deutlich zu Tage.[10]

Geteilte Kriegserfahrung: Erich Kaufmann und Carlo Schmid als Offiziere im Ersten Weltkrieg. Fotos: UB der HU zu Berlin, Porträtsammlung: Erich Kaufmann; AdSD 6/FOTA020638.

Die Kollektiv-Erfahrung der Niederlage hatte für das Institut eine bedeutende soziale Funktion: Der „Kampf gegen Versailles“ integrierte die Angehörigen des KWI über ihre politischen Differenzen hinweg. Somit gab es durchaus eine gewisse „Diversität“ im Institut, an dem mit Erich Kaufmann, Hermann Heller und Gerhard Leibholz sogar jüdische Forscher und politische Gegner zusammenfanden. Die Differenzen, die zwischen den Sozialdemokraten Heller und Carlo Schmid auf der einen und Nationalkonservativen wie Kaufmann oder Berthold von Stauffenberg auf der anderen Seite bestanden, bedürfen keiner Erläuterung. Diversität bringen weiter Referentinnen wie Ellinor von Puttkamer, Marguerite Wolff oder Angèle Auburtin. Der Kitt, der diese Gegensätze überbrückte, war die Absicht, die Nachkriegsordnung zu revidieren. Sie erleichterte die Zusammenarbeit, auch über 1933 hinaus. Gewiss hatte die Leitung die jüdischen Mitarbeiter Erich Kaufmann und Marguerite Wolff aus dem Institut verdrängt, gleichwohl gab es bis 1944 ein Miteinander aus völkischen Juristen wie Herbert Kier und Georg Raschhofer mit politisch Unangepassten wie Wilhelm Wengler, Regime-Zweiflern wie Hermann Mosler und später Berthold von Stauffenberg.

Die wissenschaftliche Begleitung des Krieges

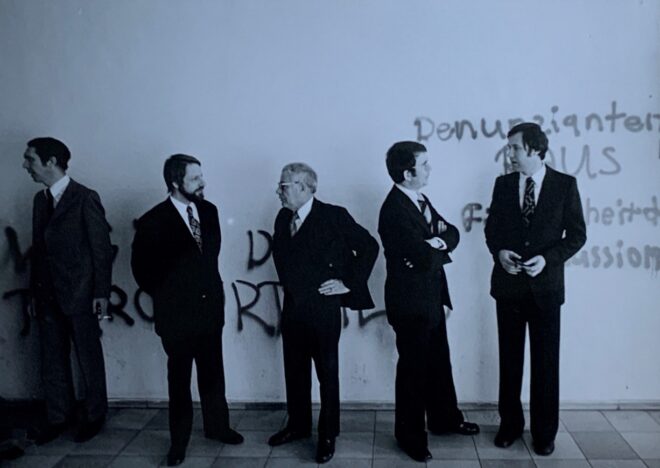

Viktor Bruns, Die Schuld am „Frieden“ und das deutsche Recht am Sudentenland, Jahrestagung KWG 1938 (Bruns dritter von rechts, neben Max Planck, zweiter von rechts)[12]

Die positive Haltung des Instituts gegenüber dem Nationalsozialismus versteht sich vor allem aus der Niederlage im Ersten Weltkrieg. Viktor Bruns und seine Mitarbeiter hofften auf die Revision des Versailler Vertrages und die Wiederherstellung einer deutschen Großmachtstellung.[13] So war das Institut schon früh in die Kriegsvorbereitungen des Dritten Reiches involviert. Bereits 1934 schuf Bruns eine eigene Abteilung für Kriegsrecht, der Berthold von Stauffenberg vorstand.[14] Ab 1935 kooperierte das KWI mit der „Deutschen Gesellschaft für Wehrpolitik und Wehrwissenschaften“, einem NS-Thinktank zu Kriegsfragen. Dessen „Ausschuss für Kriegsrecht“ hatte das Ziel, „das heterogene Kriegsrecht zu vereinfachen und – im Hinblick auf einen kommenden Krieg – alle notwendigen Unterlagen zu sammeln, um nach einem siegreichen Abschluß des Krieges die deutschen Interessen (…) möglichst gut vertreten zu können“.[15] Neben Viktor Bruns, Hermann Mosler, Ernst Schmitz und Berthold von Stauffenberg waren Angehörige von Auswärtigem Amt, Reichsjustizministerium, Oberkommando der Wehrmacht und der Marine und des Reichsluftfahrtsministeriums beteiligt.[16] Er erarbeitete eine Prisenordnung (hierfür verantwortlich war Berthold von Stauffenberg), eine Prisengerichtsordnung und Teile einer Luftkriegsordnung. Sie waren, das ist ihnen zu Gute zu halten, stark am Kriegsvölkerrecht orientiert.

Es ist festzuhalten, dass das KWI sich an der Vorbereitung eines neuen Krieges beteiligte und damit nationalsozialistische Politik unterstützte, jedoch zumeist im Rahmen des Völkerrechts.[17] Die Grenzen dieser Unterstützung wurden denn auch mit dem Bekanntwerden der grob völkerrechtswidrigen Kriegsführung an der Ostfront erreicht. Wenngleich das Institut deswegen nicht zu einem Zentrum des Widerstands wurde, so haben sich Schmitz, Wengler, Mosler und Stauffenberg doch „strikt für humanitäres Völkerrecht“ bei der Kriegsführung eingesetzt.[18] Die ebenso bedeutende wie komplexe Frage seiner Involvierung beim Attentat vom 20. Juli 1944 kann hier nicht ausgeführt werden.[19]

„Kriegsfolgenforschung“

Auch der verlorene Zweite Weltkrieg war eine Erfahrung, die die Angehörigen der Institution prägte. Die Niederlage mit all‘ ihren Konsequenzen, die Zerstörung des Berliner Schlosses, die dramatische Rettung der Institutsbibliothek, der Tod von Kollegen, ist in Zeitzeugenberichten und Nachrufen in der ZaöRV greifbar.[20]

Bis zu seiner Neu-Gründung durch die Max-Planck-Gesellschaft 1949 in Heidelberg befand sich das Institut in einem höchst prekären Zustand. Teile des Inventars befanden sich bereits in Heidelberg, ein Großteil jedoch noch im zerstörten Berlin, insbesondre im Privathaus der Familie Bruns. In dieser Zeit befassten sich die Institutsmitarbeiter vor allem mit der rechtlichen Erfassung der als „Kriegsfolgen“ verbrämten Niederlage. Carl Bilfinger war als Gutachter in alliierten Kriegsverbrecherprozessen für die I.G.-Farben sowie für die Industriellen Hermann Röchling und Friedrich Flick tätig, Hermann Mosler trat vor dem Internationalen Militärtribunal in Nürnberg für Gustav Krupp und Albert Speer auf.[21] Bis in die 1960er Jahre verfasste das Institut zahlreiche Gutachten zu Fragen des Besatzungsrechtes, Reparationen, des Status von Berlin und der Sowjetischen Besatzungszone.[22]

Boltzmannstraße 1 in Berlin. Die Direktorenvilla des KWI für Biologie beherbergte von 1947 bis 1960 die Berliner Zweigstelle des MPIL [23]

In der ersten Nachkriegsausgabe der ZaöRV 1950 definierte der trotz seiner eindeutigen NS-Belastung als Direktor wiederberufene Carl Bilfinger die Forschungsaufgaben des Instituts. Ohne den Nationalsozialismus, den Zweiten Weltkrieg, die deutschen Verbrechen auch nur zu erwähnen ging es ihm vor allem um eine Kritik der Behandlung Deutschlands durch die Alliierten. Er setzte die Lage 1950 mit der des Berliner Instituts in den 1920ern gleich: „Die Zeitschrift des Instituts befindet sich auch insoweit in einer neuen, zwar schon nach dem ersten Weltkrieg diskutierten, aber nicht voll geklärten Situation gegenüber einer alten Fragestellung.“[24] Als Hauptleistung von Bruns‘ KWI lobte Bilfinger, dieses habe Deutschlands Gegner „zur Demaskierung ihres rein machtpolitischen Standpunktes gezwungen“,[25] womit er das Heidelberger Institut in diese Linie stellte. Bilfinger sah Deutschland als Opfer der Alliierten. Von seiner restaurativen Konzeption der Nachkriegsordnung war bereits die Rede.

Die Alternative: Westintegration

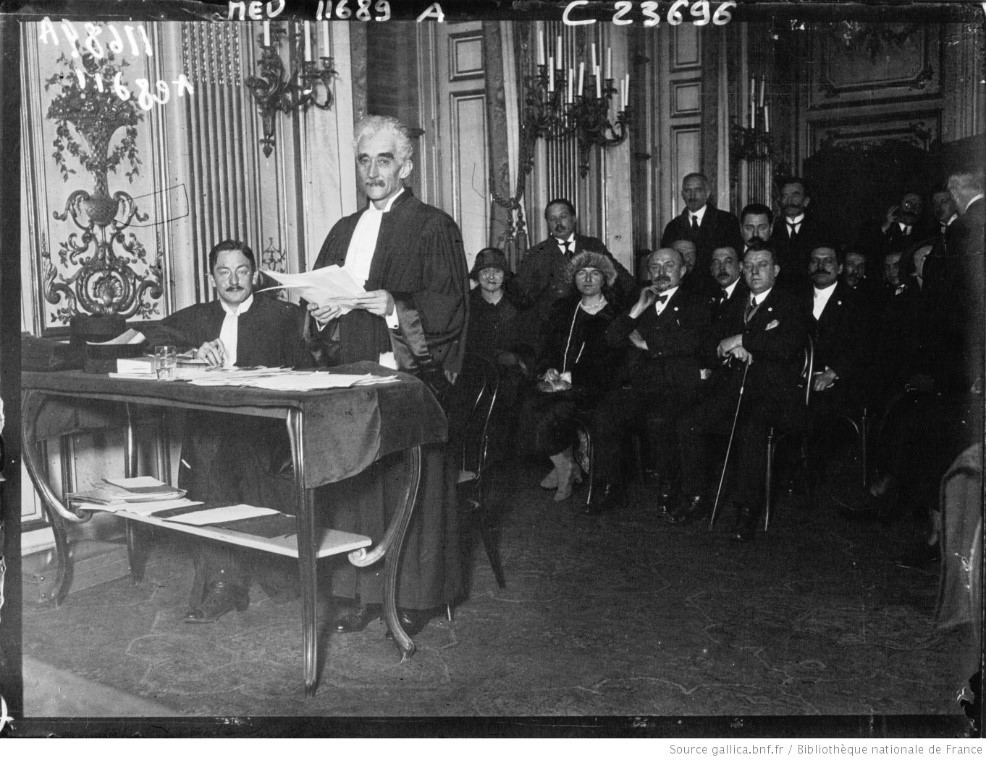

Vordenker der europäischen Integration: Walter Hallstein hält 1962 am MPIL den Vortrag „Die EWG politisch gesehen). Am Tisch Hermann Mosler und Hans Dölle. Links im Hintergrund hört eine Schar junger Referenten zu, dritter von rechts ist Rudolf Bernhardt. [26]

Ganz andere Lehren zog Hermann Mosler aus der deutschen Niederlage. Mosler, Direktor ab 1954, entwickelte ein Verständnis des EGKS-Vertrags, welches das überkommene Völkerrecht im Sinne Schumans sprengte. Auch im Weiteren begleitete er eng die Westintegration Konrad Adenauers. Dem folgten letztlich alle nachfolgenden Direktoren. So hatte der rote Faden eine neue Richtung.

In den 1950ern und 1960ern dominierten am Institut Studien, welche die Westintegration begleiteten. Im Fokus stand die europäische Integration mit ihren vielen Aspekten, Menschenrechte, Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit sowie die vielen Themen, welche die deutsche Außenpolitik in der Verarbeitung der Niederlage beschäftigten. Als die Ostpolitik ab den späten 1960er Jahren eine weitere Dimension der deutschen Niederlage zu bearbeiten begann, wurde dies selbstredend zu einem zentralen Thema. Zugleich ließ der rote Faden vieles offen: Der Umgang mit der wichtigsten Kriegsfolge, der deutschen Teilung, polarisierte wie kaum ein anderes Thema.[27] Der rote Faden findet sich just darin, dass diese Frage so wichtig war, dass sie polarisieren konnte.

Viele Mitglieder und Mitarbeiter des Instituts, allen voran Karl Doehring, Hartmut Schiedermair, Fritz Münch, aber auch Helmut Steinberger und Hermann Mosler, sahen die Ostverträge, die eine Reihe von Verträgen mit osteuropäischen Staaten, allen voran der UdSSR, Polen und später der DDR umfassten, kritisch.[28] Mit Jochen Frowein und dessen Grundlagenwerk zum „De facto Regime“ hatte das Institut aber zugleich einen Vordenker der neuen Ostpolitik in seinen Reihen.[29] Wir sehen hierin einen Beitrag zu Willy Brandts Nobelpreis. Auf jeden Fall prägte die „deutsche Frage“ als die offensichtlichste Folge der Niederlage Generationen von Wissenschaftlern. So begann auch mit der Wiedervereinigung die Präsenz der Niederlagen sich langsam zu verlieren.

Die Niederlagen im Institut des 21. Jahrhunderts

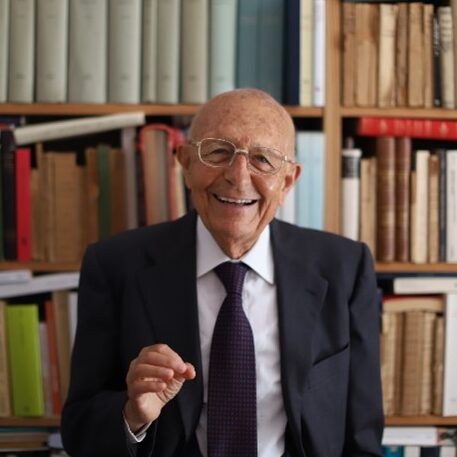

Fortleben soldatischen Stolzes, Karl Doehring (rechts) im Gespräch mit Gerhard Gutmachter, früherer Richter am Landgericht Heidelberg, anlässlich der Feier von Doehrings 80. Geburtstag am 22.03.1999 im Institut. Das Eiserne Kreuz weist den Gutmacher als hochdekorierten Teilnehmer des Zweiten Weltkrieges aus. [30]

Mit Karl Doehring und Rudolf Bernhardt starben 2011 und 2021 die letzten Direktoren mit Kriegserfahrung.[31] Wo stehen Bewusstsein, Verständnis und Relevanz der beiden Kapitulationen heute? Mit dem Gang der Zeit und der Internationalisierung des Institutspersonals ist ein Verblassen unausweichlich. Zudem haben heute viele Mitarbeitenden in der Wissenschaft, aber auch in der Bibliothek und in der Verwaltung eine Migrationsgeschichte, haben ihre Sozialisation und Ausbildung im Ausland erfahren.

Und doch gilt die Erfahrung, welche der historische Institutionalismus mit den Begriffen der critical juncture und der Pfadabhängigkeit artikuliert. Wir hoffen, mit diesem Beitrag unseren Lesern einen Faden gegeben zu haben, um sich auch auf jüngste Publikationen des Instituts einen Reim zu machen, der zur Lage Deutschlands spricht. Falls der Faden nicht mehr rot oder vielleicht gar nicht mehr auffindbar ist, so ist das auch erkenntnisträchtig. Man mag sich dann nämlich fragen, ob die Wissenschaftlerin, das Institut, Deutschland die Niederlagen vergessen, verwunden oder ‚bewältigt‘ hat, und weiter, ob man dies feiern oder aber bedauern sollte. Für uns gilt letzteres.

[1] Giovanni Capoccia, Critical Junctures, in: Orfeo Fioretos/Tulia G. Falleti/Adam Sheingate (Hrsg.), The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2016, 89-106.

[2] Jan Stöckmann, The Architects of International Relations. Building a Discipline, Designing the World, 1914-1940, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2022, 97-98.

[3] Jan-Holger Kirsch, „Wir haben aus der Geschichte gelernt“. Der 8. Mai als politischer Gedenktag in Deutschland, Köln: Böhlau 1999, 8; Reinhart Koselleck, Erfahrungswandel und Methodenwechsel. Eine historisch-anthropologische Skizze (1988), in: Reinhart Koselleck, Zeitschichten. Studien zur Historik, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 2000, 27-77; 68-69.

[4] Denkschrift über die Errichtung eines Institutes für internationales öffentliches Recht der Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften (undatiert, jedoch vor Dezember 1924), BArch, R 1501, pag. 3-10, pag. 3.

[5] Foto: BArch, Bild 183-U0628-501/ Erich O. Krueger.

[6] Ingo Hueck, Die deutsche Völkerrechtswissenschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Das Berliner Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, das Hamburger Institut für Auswärtige Politik und das Kieler Institut für Internationales Recht, in: Doris Kaufmann (Hrsg.), Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Bestandaufnahme und Perspektiven der Forschung, Göttingen: Wallstein 2000, Bd. 2, 490-528, 510.

[7] Erich Kaufmann, Das Wesen des Völkerrechts und die clausula rebus sic stantibus, Tübingen: Mohr 1911.

[8] Michael Wildt, Generation des Unbedingten. Das Führungskorps des Reichssicherheitshauptamtes, Hamburg: Hamburger Edition 2002; Ulrich Herbert, Best. Biographische Studien über Radikalismus, Weltanschauung und Vernunft 1903–1989, München: Beck 2016.

[9] Siehe: Herbert (Fn. 8) 54; Samuel Salzborn, Zwischen Volksgruppentheorie, Völkerrechtslehre und Volkstumskampf. Hermann Raschhofer als Vordenker eines völkischen Minderheitenrechts, Sozial.Geschichte 21(2006), 29-52, 33.

[10] Carlo Schmid, Erinnerungen, Stuttgart: Hirzel 2008, 40 ff.; Friedrich Berber, Zwischen Macht und Gewissen. Lebenserinnerungen, München: Beck 1986, 13-18; Joachim von Elbe, Unter Preußenadler und Sternenbanner. Ein Leben für Deutschland und Amerika, München: Bertelsmann 1983, 54-57.

[12] Foto:Weltbild Foto Verlag. Das Originalbild war in besserer Ausführung nicht auffindbar. Recherchen im Bundesarchiv, im Bildarchiv der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz und bei Ullstein Bild und beim Scherl-Archiv/SZ-Foto, die Teile des Weltbild-Bestandes übernommen haben, blieben erfolglos. Für weitere Informationen wären wir dankbar.

[13] Vgl. etwa: Viktor Bruns, Die Schuld am „Frieden“ und das deutsche Recht am Sudetenland, 31.05.1938, in: Ernst Telschow (Hrsg.), Jahrbuch 1939 der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, Leipzig: Drugulin 1939, 57-85.

[14] Andreas Toppe, Militär und Kriegsvölkerrecht. Rechtsnorm, Fachdiskurs und Kriegspraxis in Deutschland 1899-1940, München: De Gruyter 2008; 207; Andreas Meyer, Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (1905-1944). Völkerrecht im Widerstand, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2001, 60.

[15] Meyer (Fn. 14), 64.

[16] Toppe (Fn, 14), 207.

[17] Ernst Schmitz, Vorlesung Kriegsrecht 1938, unveröffentlichtes Manuskript, in der Bibliothek des MPIL vorhanden unter der Signatur: VR: XVII H: 40; ferner überliefert sind die Gutachten Hermann Moslers, ohne Signatur, MPIL; ferner: Hueck (Fn. 6), 512. Felix Lange, Praxisorientierung und Gemeinschaftskonzeption. Hermann Mosler als Wegbereiter der westdeutschen Völkerrechtswissenschaft nach 1945, Heidelberg: Springer 2017, 76.

[18] Hueck (Fn. 6), 522.

[19] Hueck (Fn. 6), 522..

[20] Die Nachkriegs-ZaöRV, Band 13 im Jahre 1950, beginnt mit sechs Nachrufen. Durch den Krieg kamen Joachim-Dieter Bloch ums Leben, der bei der Befreiung Berlins von Rotarmisten erschossen wurde, Alexander N. Makarov, Joachim-Dieter Bloch (1906-1945), ZaöRV 13 (1950), 16-18; Der 22-jährige Referent Ferdinand Schlüter galt seit 1944 als vermisst. „Die alten Gefährten des Instituts bewahren ihm ein treues Andenken und haben die Hoffnung auf seine Rückkehr noch nicht aufgegeben“, Helmut Strebel, Ferdinand Schlüter (vermißt), ZaöRV 13 (1950), 20-21, 21; Eindrucksvoll der Zeitzeugenbericht der Bibliothekarin Annelore Schulz, Die Rückführung unserer Institutsbibliothek aus der Uckermark nach Berlin-Dahlem, 1946 (unveröffentlicht).

[21] Lange (Fn. 17), 150; Hubert Seliger, Politische Anwälte? Die Verteidiger der Nürnberger Prozesse, Baden-Baden: Nomos 2016, 181; 548; Philipp Glahé/Reinhard Mehring/Rolf Rieß (Hrsg.). Der Staats- und Völkerrechtler Carl Bilfinger (1879-1958). Dokumentation seiner politischen Biographie. Korrespondenz mit Carl Schmitt, Texte und Kontroversen, Baden-Baden: Nomos 2024, 329.

[22] Hierzu siehe umfangreiche Gutachtensammlung im MPIL-Bestand. Die bis 1960 bestehende Berliner Abteilung des Instituts war vor allem dem Kriegsfolgenrecht gewidmet. In den 1950er Jahren wurden ferner zwei bedeutende juristische Archivbestände vom MPI übernommen, das „Heidelberger Dokumentenarchiv“, das einen vollen Satz der Prozessunterlagen der Nürnberger Prozesse umfasst und Teile der Bestände des „Instituts für Besatzungsfragen“, das in Tübingen angesiedelt war und u.a. zu alliierten Besatzungsrechtsverstößen forschte, siehe Bestand im MPIL-Keller; Hermann Mosler, Der Einfluss der Rechtsstellung Deutschlands auf die Kriegsverbrecherprozesse, Süddeutsche Juristenzeitung 2 (1947), 362-370; Hermann Mosler, Die Kriegshandlung im rechtswidrigen Kriege, in: Forschungsstelle für Völkerrecht und ausländisches öffentliches Recht der Universität Hamburg/Institut für internationales Recht an der Universität Kiel, Jahrbuch für internationales und ausländisches öffentliches Recht 1948, Bd. 2, Hamburg: Hansischer Gildenverlag 1948, 335-358.

[23] Foto: AMPG.

[24] Carl Bilfinger, Prolegomena, ZaöRV 13 (1950), 22-26, 26.

[25] Carl Bilfinger, Völkerrecht und Historie, in: Boris Rajewski/Georg Schreiber (Hrsg,), Aus der deutschen Forschung der letzten Dezennien. Dr. Ernst Telschow zum 65. Geburtstag gewidmet, Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag 1954, 29-32, 30.

[26] Foto: MPIL.

[27] Hiervon zeugen die überlieferten Protokolle der Referentenbesprechungen.

[28] Felix Lange, Zwischen völkerrechtlicher Systembildung und Begleitung der deutschen Außenpolitik.

Das Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, 1945–2002, in: Thomas Duve/Jasper Kunstreich/Stefan Vogenauer (Hrsg.), Rechtswissenschaft in der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, 1948–2002, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2023, 26.

[29] Jochen Frowein, Das de facto-Regime im Völkerrecht, Köln: Carl Heymanns Verlag 1968.

[30] Foto: MPIL.

[31] Bernhardt schien sich zeitlebens nicht zu dieser Erfahrung geäußert zu haben, in seiner Privatbibliothek dominierten aber Werke, die sich mit dem Phänomen des Nationalsozialismus auseinandersetzten. Anders: Karl Doehring, Von der Weimarer Republik zur Europäischen Union. Erinnerungen, Berlin: wjs 2008, 71-114. Zu Rudolf Bernhardts Erfahrungen in der Kriegsgefangenschaft: Rudolf Bernhardt, Tagebuchaufzeichnungen aus sowjetischer Kriegsgefangenschaft 1945-1947, hrsg. von Christoph Bernhardt, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag 2024.

English

The capitulations at the end of the First and Second World Wars are regarded as defeats for Germany, not only for its army or government. They represent deep social caesuras and continue to characterise the German path to this day, including that of the Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law. We perceive these capitulations as critical junctures [1] and will demonstrate that they form a common thread that links many of the Institute’s positions and runs through its research. The Geneva Institut de hautes études internationales, which accompanied the new order from a victor’s perspective from 1927 onwards, forms a contrasting foil.[2] The thread of defeat dominates the Institute in the inter-war period and the early Federal Republic, yet also taps into many aspects of the Institute’s more recent history. It can be found in the studies on German unity and on European integration after the fall of the iron curtain, on international law as a value-based order, as well as on global constitutionalism. Certainly, it loses some of its interpretative power with increasing historical distance and with the internationalisation of the MPIL. This article opens shows the common thread on the basis of the formative positioning of the institute in the Weimar Republic and its repositioning in the young Federal Republic of Germany.

Please note, we propose as the red thread the interpretation of the capitulations as formative German defeats. This interpretation is almost universally shared, in stark contrast to the understanding of the causes of the wars, war guilt, and the extent and uniqueness of Germany’s crimes. Moreover, our thesis is not monocausal or deterministic: further causes have been shaping the Institute’s path.[3] The red thread we are describing by no means follows a straight path: After the first defeat, the Institute aimed to revise the post-war international legal order, whereas after the second defeat it aimed to for its consistent development. The assertion of a common thread also does not claim a consensus in the assessment or the consequences that were drawn. Many contributions to this blog show the sometimes-astonishing pluralism in how the defeats were dealt with within the Institute. Our common thread can only be a common thread because it leaves many aspects open and up for debate. In a nutshell: we are not writing a narrative.

A Loser’s Institution

The foundation of the institute on 19 December 1924 was a result of the capitulation. Having lost the war, Germany had to submit to a new international order dominated by its opponents. The defeat presented the German international lawyers and the entire discipline with unprecedented challenges. They now stood alone, without a powerful army at their side. Moreover, the Treaty of Versailles confronted Germany with intricate international problems, such as the loss of territory, restrictions on sovereignty, enormous reparations, war debts and political isolation. In addition, Germany suffered from a lack of competent lawyers. The statism of the German Empire had little interest in international law, so the discipline was neglected for decades.

The establishment of the Institute responded to this situation. The founding memorandum, written by KWG Secretary General Friedrich Glum, the eminent Weimar professor Heinrich Triepel and the founding director Viktor Bruns stated:

“In the decades to come, Germany will have to deal more than ever with the cultivation of international relations, in order to protect itself from the unjustified claims of its war enemies, to help its compatriots in the ceded territories and to reassert itself in the world.” [4]

The Institute started a “loser’s institution”. The consequences of this, however, could turn out very differently, leading for example to a critical or an emphatic understanding of international law. One obvious consequence could have been a critical understanding of international law as an instrument of the strong to suppress the weak, ‘the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must’. The Institute decided differently, more wisely: a country with a Wehrmacht of only 100,000 men is better served by an understanding of international law according to which law is more than just the formalisation of power. Corresponding to the interests at stake is an understanding as an independent system of order, which also serves to inhibit pure power. It is therefore by no means a coincidence that Bruns’ programmatic first article in the Institute’s newly founded journal theorizes the autonomy of international law: “International Law as a Legal Order“.

The KWI’s approach to the defeat was not the only possible. Consider the Hamburg Institut für auswärtige Politik (“Institute for Foreign Policy”), founded in 1922 by Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy, and the Kiel Institut für Internationales Recht (“Institute for International Law”) under the directorship of Walther Schücking. These two institutes also addressed the defeat, but with a more progressive understanding of international law committed to the international order and the League of Nations. Such commitments do not characterise the work of the KWI. Even ‘international law as a legal order’ appears to be more a means than an end. After the Second World War, this openness in dealing with the defeat was even evident internally.Whereas Carl Bilfinger (1879-1958), who oversaw the re-foundation of the institute in 1950, , recommended a peace order based on the balance of power according to the traditional model of the Congress of Vienna, his successor Hermann Mosler (1912-2001) focussed on theintegration into the West that ‘detonated’ (“sprengen”) traditional thinking.

Concrete Experiences of Defeat

The burned-out castle in June 1946[5]

The influential power of the defeats can be concretised by looking at the members of the institute. Looking at the staff structure of the KWI, it was “comparable to that at the Federal Foreign Office: aristocratic origins, bourgeois tradition and a certain social arrogance dominated.“[6] Due to an, in many cases, starkly nationalist sentiment, many felt the defeat particularly deeply. This is most evident in the leadership of the Institute, its founder Viktor Bruns (1884-1943), and the academic members and advisors Rudolf Smend (1882-1975), Erich Kaufmann (1880-1972) and from 1944 onwards by the second director, Carl Bilfinger (1879-1958). Among them, Erich Kaufmann, a highly decorated soldier, was the only one who had served in the war, which he had almost yearned for in his famous – by now infamous – bellicose essay on the “Nature of International Law” (“Das Wesen des Völkerrechts”).[7] Viktor Bruns and Heinrich Triepel were among the more than 3,000 professors who had signed the nationalistic “Declaration of the Professors of the German Empire” (“Erklärung der Hochschullehrer des Deutschen Reiches”) in 1914 and consequently showed active support of the war.

Among staff members, only a few, such as Hermann Heller (1891-1933), Carlo Schmid (1896-1979) and Friedrich Berber (1898-1984), had fought in the First World War. Most had experienced the war as teenagers, such as Joachim Dieter Bloch (1906-1945), Karl Bünger (1903-1997), Joachim von Elbe (1902-2000), Herbert Kier (1900-1973) and Gerhard Leibholz (1901-1982), Hans-Joachim von Merkatz (1905-1982), Hermann Mosler (1912-2001), Hermann Raschhofer (1905-1979), Helmut Strebel (1911-1992), Ulrich Scheuner (1903-1981), Berthold von Stauffenberg (1905-1944) and Wilhelm Wengler (1907-1995).[8] Yet, educated in the spirit of German nationalism and subject to the war propaganda, they were characterised by a strange bitterness: For not fighting in the war to avoid defeat, they felt to have missed the opportunity to prove themselves to their nation, and many tried to make up in other ways.[9] Some have reported on the experience of defeat in autobiographies.[10]

Shared war experience: Erich Kaufmann in 1918 and Carlo Schmid in 1917 as officers (Photos: UB der HU zu Berlin, Porträtsammlung: Erich Kaufmann; AdSD 6/FOTA020638).

The shared experience of defeat had an important social function for the Institute: the “fight against Versailles” integrated the members of the KWI beyond their political differences. Indeed, there was a certain degree of “diversity” at the Institute. It provided a space for researchers of Jewish origin such as Erich Kaufmann, Hermann Heller and Gerhard Leibholz. There was also political diversity, and the differences between the social democrats Heller and Carlo Schmid on the one hand and conservatives such as Kaufmann or Berthold von Stauffenberg ran deep. It is worth mentioning diversity for female researchers such as Ellinor von Puttkamer, Marguerite Wolff and Angèle Auburtin.

The glue among the members was the intention to revise the post-war order. This shared objective facilitated cooperation among the Institute’s members, even after 1933. It is true that the Jewish members Erich Kaufmann and Marguerite Wolff were forced out. However, until 1944, political nonconformists such as Wilhelm Wengler, regime-sceptics such as Hermann Mosler and, later, the dissident and member of the resistance movement of 20 July 1944 Berthold von Stauffenberg worked with national socialist lawyers such as Herbert Kier and Georg Raschhofer.

Scientific Support of the War

Viktor Bruns, The Guilt of “Peace” and the German Right to the Sudetenland, Annual Conference of theKWG 1938 (Bruns third from right, next to Max Planck, second from right) [12]

The Institute’s support of National Socialism can be explained with the defeat in the First World War, not with deep belief in the regime’s ideology. Viktor Bruns and his staff longed for a revision of the Treaty of Versailles and the restoration of Germany as a great power.[13] With this aim, the Institute became involved in the Third Reich’s war preparations early on. Already in 1934, Bruns set up a department for martial law, headed by Berthold von Stauffenberg.[14] From 1935, the Institute participated in the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wehrpolitik und Wehrwissenschaften (“German Society for Defence Policy and Defence Sciences”), a Nazi think-tank on war issues. Its Ausschuss für Kriegsrecht (“Committee for the Law of War”) aimed to “simplify the heterogeneous law of war and – in view of a coming war – to collect all the necessary documents in order to be able to represent German interests as well as possible after the German victory.”[15] In this think tank, Viktor Bruns, Hermann Mosler, Ernst Schmitz and Berthold von Stauffenberg joined members of the Foreign Office, the Ministry of Justice, the High Command of the Wehrmacht and the Navy, and the Ministry of Aviation.[16] It developeda draft for a prize law (“Prisenordnung”), for which Berthold von Stauffenberg was responsible, as well as a law of admiralty courts and parts of a law on aerial warfare. These were, to their credit, heavily oriented on the international law of war.While the KWI was involved in preparing a new war and supported Nazi policy, it was so mostly within the limits of international law.[17] Thus, its support weakened when the gross violation of international law on the Eastern Front became known. Although the Institute did not become a centre of resistance, there is evidence that Schmitz, Wengler, Mosler and Stauffenberg were “strictly committed to international humanitarian law”. [18] An issue of both great relevance and complexity is Stauffenberg’s involvement in the operation Walküre of 20 July 1944.[19] It can, however, not be discussed here.

“Kriegsfolgenforschung” -“Research on the Consequences of the War”

The defeat in the Second World War with all its consequences, the destruction of Berlin Palace, the dramatical rescue of the institute’s library, and the deaths of colleagues, was another experience impacting the institute’s staff. Much of this becomes tangible in the eyewitness accounts and obituaries in the ZaöRV.[20] Until the Institute’s re-establishment by the newly founded Max Planck Society in Heidelberg in 1949, it was in a most precarious state. Parts had already been moved to Heidelberg where Bilfinger was living, but much of the library and staff were still in Berlin, but in Bruns’ villa. The Institute’s staff was primarily concerned with the legal side of the defeat, euphemistically termed “the law of the consequences of war” (Kriegsfolgenrecht). Carl Bilfinger worked for the industrialists Hermann Röchling and Friedrich Flick in the Allied war crimes trials, while Hermann Mosler appeared on behalf of Gustav Krupp and Albert Speer.[21] Until the 1960s, the Institute was busy with questions of the law of occupation, reparations, and the status of Berlin and the Soviet occupation zone.[22]

Boltzmannstraße 1 in Berlin. The Director’s Villa of the KWI for Biology housed the Berlin branch of the MPIL from 1947 to 1960[23]

In the first post-war issue of the ZaöRV in 1950, Carl Bilfinger, reappointed as director despite his Nazi background, defined the Institute’s research tasks. Without any mentioning National Socialism, the Second World War or German crimes, he was primarily concerned with criticising the treatment of Germany by the Allies. He compared the situation in 1950 with that of the Berlin Institute in the 1920s: “In this respect, the journal of the Institute also finds itself in a new situation, which was already discussed after the First World War, but not fully clarified, in relation to an old question.” [24] Bilfinger praised the main achievement of Bruns’s KWI as having “forced Germany’s opponents to unmask their purely power-political standpoint”, thus placing the Heidelberg Institute in this line. [25] Bilfinger saw Germany as a victim of the Allies. His restorative conception of the post-war order has already been mentioned.

The Alternative: The Federal Republic’s Integration into the West

Protagonist of European integration: Walter Hallstein gives a lecture on “The EEC seen from a political point of view” at the MPIL in 1962. Hermann Mosler and Hans Dölle at the table. In the background on the left, a group of young researchers listening, third from the right is Rudolf Bernhardt, later director of the Institute.[26]

Hermann Mosler drew very different lessons from Germany’s defeat. Mosler, who took over as director in 1954, developed a new understanding of the ESCS treaty, which transcended traditional international law according to Schuman. Generally, he closely followed and supported Konrad Adenauer’s Western integration. All subsequent directors followed suit, and thus the red thread took on a new direction.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the research agenda of the Institute was dominated by studies accompanying this integration of the West: European integration in its many aspects, human rights, and, on the comparative side, constitutional adjudication and the control of the executive. When, in the late 1960s, the Ostpolitik began to address a further dimension of the German defeat, this naturally became a central issue. At the same time, the red thread left much open, namely how to deal with the most visible consequence of the defeat: the division of Germany and its loss of territory. The issue was a polarising the Institute as it was polarizing the country.[27] The red thread is that the issue was so important that it could polarise the Institute.

Many members and staff of the Institute, above all Karl Doehring, Hartmut Schiedermair, Fritz Münch, but also Helmut Steinberger and Hermann Mosler, rejected the Ostverträge, a series of treaties of the Federal Republic with the Eastern European countries, above all the Soviet Union, Poland and later the German Democratic Republic.[28] But with Jochen Frowein and his fundamental work on the “de facto regime”, the Institute had also produced much of the legal thought of the new Ostpolitik. [29] We see this as a contribution to Willy Brandt’s Nobel Peace Prize. In any case, the “German question”, as the most obvious consequence of the defeat, had a formative influence on generations of researchers. Consequently, with German reunification, the presence of the defeat slowly began to fade.

The Defeats and the Institute in the 21st century

he Continuous Relevance of Military Pride. Karl Doehring (right) in conversation with Gerhard Gutmacher, former judge at the Landgericht Heidelberg, on the occasion of Doehring’s 80th birthday on 22 March 1999 at the Institute. The Iron Cross identifies the guest as a highly decorated participant in the Second World War.[30]

Karl Doehring and Rudolf Bernhardt, the last directors with war experience, died in 2011 and 2021 respectively. [31] What is the awareness, understanding and relevance of Germany’s capitulations today? With the passage of time and the internationalisation of the MPIL’s staff, fading is inevitable, not least because many of today’s academic, library and administrative staff have a history of migration and were socialised and educated abroad.

And yet, historical institutionalism’s concepts of critical juncture and path dependency express a deep truth. With this article, we hope to have provided our readers with a thread leading towards a grasp of the Institute’s most recent publications, and by that, also of the situation in Germany more broadly. If the thread is no longer red or even has become impossible to find, this is also significant. Then one might ask whether researchers, the institute, and Germany have forgotten, overcome, or coped with the defeats and whether this should be reason for celebration or for regret. For us it would be the latter.

[1] Giovanni Capoccia, Critical Junctures, in: Orfeo Fioretos/Tulia G. Falleti/Adam Sheingate (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2016, 89-106.

[2] Jan Stöckmann, The Architects of International Relations. Building a Discipline, Designing the World, 1914-1940, Cambridge 2022, 97-98.

[3] Jan-Holger Kirsch, „Wir haben aus der Geschichte gelernt“. Der 8. Mai als politischer Gedenktag in Deutschland, Köln: Böhlau 1999, 8; Reinhart Koselleck, Erfahrungswandel und Methodenwechsel. Eine historisch-anthropologische Skizze (1988), in: Reinhart Koselleck, Zeitschichten. Studien zur Historik, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 2000, 27-77; 68-69.

[4] Memorandum on the foundation of the Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (undated, but drafted before December 1924), BArch, R 1501, 3-10, 3, translated by the authors.

[5] Photo: BArch, Bild 183-U0628-501/ Erich O. Krueger.

[6] Ingo Hueck, Die deutsche Völkerrechtswissenschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Das Berliner Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, das Hamburger Institut für Auswärtige Politik und das Kieler Institut für Internationales Recht, in: Doris Kaufmann (ed.), Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Bestandaufnahme und Perspektiven der Forschung, Göttingen: Wallstein 2000, Vol. 2, 490-528, 510.

[7] Erich Kaufmann, Das Wesen des Völkerrechts und die clausula rebus sic stantibus, Tübingen: Mohr 1911.

[8] Michael Wildt, Generation des Unbedingten. Das Führungskorps des Reichssicherheitshauptamtes, Hamburg: Hamburger Edition 2002; Ulrich Herbert, Best. Biographische Studien über Radikalismus, Weltanschauung und Vernunft 1903–1989. Munich: C.H. Beck 2016.

[9] Cf. Herbert (fn. 8), 54; Samuel Salzborn, Zwischen Volksgruppentheorie, Völkerrechtslehre und Volkstumskampf. Hermann Raschhofer als Vordenker eines völkischen Minderheitenrechts, Sozial.Geschichte 21 (2006), 29-52, 33.

[10] Carlo Schmid, Erinnerungen, Stuttgart: Hirzel 2008, 40 et seqq; Friedrich Berber, Zwischen Macht und Gewissen. Lebenserinnerungen, Munich: Beck 1986, 13-18; Joachim von Elbe, Unter Preußenadler und Sternenbanner. Ein Leben für Deutschland und Amerika, Munich: Bertelsmann 1983, 54-57.

[11] Photo: University Library of the Humbolt University (Berlin), portrait collection: Erich Kaufmann; AdSD 6/FOTA020638.

[12] Photo: Weltbild Foto Verlag. The original image could not be found in a better version. Searches in the Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archive), the picture archive of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation) and the archives of Ullstein Bild and Scherl/SZ-Foto, which have taken over parts of the Weltbild collection, were unsuccessful. We would be grateful for any further information.

[13] Cf. Viktor Bruns, Die Schuld am „Frieden“ und das deutsche Recht am Sudetenland, 31.05.1938, in: Ernst Telschow (ed.), Jahrbuch 1939 der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, Leipzig: Drugulin 1939, 57-85.

[14] Andreas Toppe, Militär und Kriegsvölkerrecht. Rechtsnorm, Fachdiskurs und Kriegspraxis in Deutschland 1899-1940, Munich: De Gruyter 2008, 207; Andreas Meyer, Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (1905-1944). Völkerrecht im Widerstand, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2001, 60.

[15] Meyer (fn. 14), 64, translated by the authors.

[16] Toppe (fn. 14), 207.

[17] Ernst Schmitz, Vorlesung Kriegsrecht [“Lecture on the Law of War”] 1938, unpublished manuscript, in the MPIL’s library under signature: VR: XVII H: 40; there are also legal opinions by Hermann Moslers, without signature, MPIL; see also: Hueck (fn. 6), 512; Felix Lange, Praxisorientierung und Gemeinschaftskonzeption. Hermann Mosler als Wegbereiter der westdeutschen Völkerrechtswissenschaft nach 1945, Heidelberg: Springer 2017, 76.

[18] Hueck (fn. 6), 522.

[19] Hueck (fn. 6), 522.

[20] The post-war issue of the ZaöRV (today also under the English title Heidelberg Journal of International Law, HJIL), vol. 13 of 1950, begins with six obituaries. The war claimed the life of Joachim-Dieter Bloch, who was shot by Red Army soldiers during the liberation of Berlin, Alexander N. Makarov, Joachim-Dieter Bloch (1906-1945), HJIL 13 (1950), 16-18; the 22-year-old lecturer Ferdinand Schlüter had been missing since 1944: “The old companions of the Institute honour his memory faithfully and have not yet given up hope of his return”: Helmut Strebel, Ferdinand Schlüter (vermißt), HJIL 13 (1950), 20-21, 21; Impressive contemporary witness report by librarian Annelore Schulz, Die Rückführung unserer Institutsbibliothek aus der Uckermark nach Berlin-Dahlem [“The repatriation of our institute library from the Uckermark to Berlin-Dahlem”], 1946 (unpublished).

[21] Lange (fn, 17), 150; Hubert Seliger, Politische Anwälte? Die Verteidiger der Nürnberger Prozesse, Baden-Baden: Nomos 2016, 181, 548; Philipp Glahé/Reinhard Mehring/Rolf Rieß (Hrsg.). Der Staats- und Völkerrechtler Carl Bilfinger (1879-1958). Dokumentation seiner politischen Biographie. Korrespondenz mit Carl Schmitt, Texte und Kontroversen, Baden-Baden: Nomos 2024, 329.

[22] See the extensive collection of expert opinions in the MPIL’s holdings. The Institute’s Berlin department, which existed until 1960, was primarily concerned with the legal consequences of the war. In the 1950s, the MPI also took over two important collections of legal archives: the “Heidelberger Dokumentenarchiv”, which contains a complete set of the trial documents of the Nuremberg Trials, and parts of the certificates of the “Institut für Besatzungsfragen”, which was based in Tübingen and researched, among other things, violations of the law of the Allied occupation; see the collection in the basement of the MPIL; Hermann Mosler, Der Einfluss der Rechtsstellung Deutschlands auf die Kriegsverbrecherprozesse, Süddeutsche Juristenzeitung 2 (1947), 362-370; Hermann Mosler, Die Kriegshandlung im rechtswidrigen Kriege, in: Forschungsstelle für Völkerrecht und ausländisches öffentliches Recht der Universität Hamburg/Institut für internationales Recht an der Universität Kiel, Jahrbuch für internationales und ausländisches öffentliches Recht 1948, vol. 2, Hamburg: Hansischer Gildenverlag 1948, 335-358.

[23] Photo: AMPG.

[24] Carl Bilfinger, Prolegomena, HJIL 13 (1950), 22-26, translated by the authors.

[25] Carl Bilfinger, Völkerrecht und Historie, in: Boris Rajewski/Georg Schreiber (eds.), Aus der deutschen Forschung der letzten Dezennien. Dr. Ernst Telschow zum 65. Geburtstag gewidmet, Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag 1954, 29-32, 30.

[26] Photo: MPIL.

[27] The surviving minutes of the “Referentenbesprechung” bear witness to this.

[28] Felix Lange, Zwischen völkerrechtlicher Systembildung und Begleitung der deutschen Außenpolitik.

Das Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, 1945–2002, in: Thomas Duve/Jasper Kunstreich/Stefan Vogenauer (eds.), Rechtswissenschaft in der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, 1948–2002, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2022, 26.

[29] Jochen Frowein, Das de facto-Regime im Völkerrecht, Cologne: Carl Heymanns Verlag 1968.

[30] Photo: MPIL.

[31] Bernhardt does not seem to have commented on this experience throughout his life, but his private library was dominated by works dealing with the phenomenon of National Socialism, unlike Karl Doehring, who wrote extensively about his time as a soldier: Karl Doehring, Von der Weimarer Republik zur Europäischen Union. Erinnerungen, Berlin: wjs Verlag 2008, 71-114. On Rudolf Bernhardt’s experiences as a prisoner of war: Rudolf Bernhardt, Tagebuchaufzeichnungen aus sowjetischer Kriegsgefangenschaft 1945-1947, ed. by Christoph Bernhardt, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag 2024.

Armin von Bogdandy ist Direktor am MPIL.

Philipp Glahé ist akademischer Rat auf Zeit am Lehrstuhl für Neueste Geschichte und Zeitgeschichte am Historischen Seminar an der LMU München. Von 2022 bis 2025 war er wissenschaftlicher Referent am MPIL.