In the early 1990s, Andreas Zimmermann – then a PhD candidate at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (MPIL) in Heidelberg – comprehensively addressed the question of the conformity of so-called “safe third country” (STC) practices in the field of refugee protection with international law. In 1992, in the run-up to the reform of the German asylum system, he wrote an expert opinion together with the institute’s director at the time, Jochen A. Frowein, for the German Federal Ministry of Justice titled “Der völkerrechtliche Rahmen für die Reform des deutschen Asylrechts” (“The International LawFramework for the Reform of German Asylum Law”)[1]. Following the adoption of Article 16a of the Basic Law – the German constitution – in 1993, he wrote his PhD thesis titled “Das neue Grundrecht auf Asyl – Verfassungs- und völkerrechtliche Grenzen und Voraussetzungen” (“The New Fundamental Right to Asylum – Constitutional and International Law Limits and Requirements”).[2] The work was published in 1994 as part of the Heidelberg Max Planck Law book series “Contributions on Comparative Public Law and International Law”. It analyses in detail the legality of Article 16a of the Basic Law at the constitutional, European, and international level. Furthermore, in 1993, he also wrote an article on “Asylum Law in the Federal Republic of Germany in the Context of International Law”, which was published in the Heidelberg Journal on Comparative Public Law and International Law (HJIL).[3] In light of the current discourse surrounding the proposals for a reform of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), it is worthwhile revisiting these works.

The “Asylum Compromise” of 1993

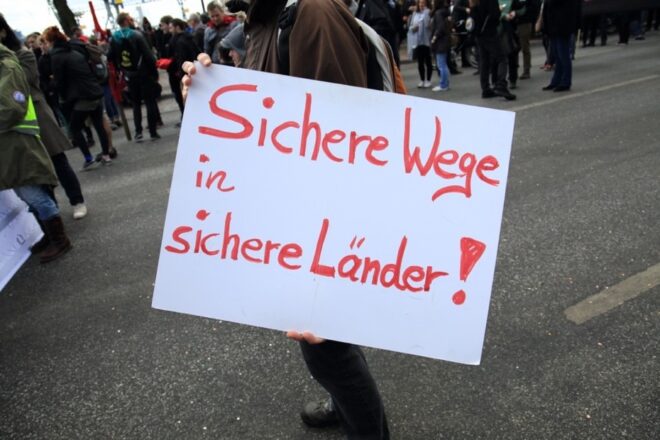

In 1993, the concept of STC was introduced to the German constitution in an effort to deal with the high influx of war refugees from the former Yugoslavia. Germany thereby followed an emerging practice that originated in Switzerland to ensure a sharing of responsibility for asylum seekers among members of the international community. States most impacted by refugee influx could reject an application for asylum as inadmissible and could subsequently send asylum seekers to another state on the condition that the receiving state could offer them adequate protection in accordance with accepted international standards.

Through the so-called “asylum compromise”, the right to asylum was severely restricted by means of changing Article 16 of the Basic Law. The previous version, formerly enshrined in Article 16(2) of the Basic Law read:

“Persons persecuted on political grounds shall have the right of asylum.”

Paragraph (2) of Article 16a of the Basic Law (introduced in 1993) stipulates:

“Paragraph (1) [the right to asylum] of this Article may not be invoked by a person who enters the federal territory from a member state of the European Communities or from another third state in which application of the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms is assured. […]”[4]

Safe Third Country Practices and International Law

Regarding the compliance of the STC concept enshrined in Paragraph (2) of Article 16a of the Basic Law with international law, Zimmermann’s main conclusions,[5] in 1993, are as follows:

Under customary international law, states are not subject to a duty to readmit persons other than their own nationals. Hence, sending an asylum seeker to a third state is only possible if that state has declared its willingness to readmit asylum seekers and provide them with the option to request refugee status in a legally binding agreement with the sending state.

Under the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention (thereinafter: Refugee Convention), states are generally not precluded from returning asylum seekers to third states. In any given case, however, it must be assured that the principle of non-refoulement, enshrined in Article 33 of the Refugee Convention, is abided by. This means that asylum seekers must be protected from persecution in the third state as well as from deportation by the third state to the presumed country of persecution (protection from chain deportations).

While STC can be determined in a generalized manner, it is necessary that the states in question are themselves bound by the Refugee Convention without geographical reservations and that their procedure of asylum application is in line with the procedural minimum standard under international law. However, even if the procedural guarantees of the Refugee Convention are generally complied with, the returning state is obliged to examine whether the receiving state fulfils its obligations under Article 33 of the Refugee Convention bona fide. In case of concrete indications that the respective third country is, in practice, not complying with the prohibition of refoulement stipulated in Article 33 of the Refugee Convention despite its formal commitment to the Convention, the returning state is obliged to review whether a country may remain on the list of STC.

Furthermore, before being sent back to a STC, a refugee must be granted an opportunity to claim that, in his or her individual case, the third state in question would not be safe.

Under the Refugee Convention, an asylum-seeker needs to be sufficiently connected to the third country in question for his or her transfer there to be legal. For example, a state has no right to return a person to a country through the airport of which he or she has passed for purposes of transit only.

Whereas the returning state must ensure that the third state abides by Article 33 of the Refugee Convention, it is not responsible for ensuring that allprovisions of the Refugee Convention are complied with in the third country.[6] Nevertheless, the third state must guarantee the refugee some kind of minimum living standard.

Under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), there are further special restrictions, e.g., with regard to the protection of family life (Article 8 ECHR) and the prohibition (under Article 3 ECHR) to create a situation where a person is permanently sent from one state to another and thus becomes a “refugee in orbit”.

Most of these findings about the legal safeguards still apply to today’s changed legal environment and have been further developed by scholarship and jurisprudence over the years. Some questions, however, remain disputed to this day: this includes whether the third state needs to be a party to the Refugee Convention and to what extent the sending state must ensure that provisions of the Refugee Convention are complied with in the third country.[7]

The Safe Third Country Concept in EU Asylum Law

In 2005, the concept of STC was incorporated at the EU-level in the 2005 Asylum Procedures Directive, which was later replaced by the 2013 Asylum Procedures Directive (rAPD). Article 38(1) rAPD stipulates that a member state may apply the STC concept only when the competent authorities are satisfied that a person seeking international protection will be treated in accordance with the following principles in the third country:

„(a) life and liberty are not threatened on account of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion;

(b) there is no risk of serious harm as defined in Directive 2011/95/EU;

(c) the principle of non-refoulement in accordance with the Geneva Convention is respected;

(d) the prohibition of removal, in violation of the right to freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment as laid down in international law, is respected; and

(e) the possibility exists to request refugee status and, if found to be a refugee, to receive protection in accordance with the Geneva Convention.”

Furthermore, according to Article 38(2)(a) rAPD, the applicant needs to be sufficiently connected to the STC, so that his or her return and seeking refuge there may be considered reasonable. If the conditions of Article 38 rAPD are met, a member state may consider an application for international protection to be inadmissible (Article 33(2)(c) rAPD).

Increasingly, restrictive immigration policies are aimed at deterring irregular arrivals and responsibility-shifting rather than responsibility-sharing. States are seeking to outsource migration management and international protection responsibility to third countries – mostly transit countries – already impacted by large refugee flows. These policies come with diminished safeguards, as demonstrated by the 2016 EU‑Turkey statement or the 2022 UK‑Rwanda agreement, the latter of which was recently declared unlawful by the UK Supreme Court on the basis that Rwanda was not a STC as asylum seekers would be at risk of refoulement.

While Article 16a of the Basic Law has lost its significance in German asylum law practice since the main regulations are now contained in international treaty law and EU law, the underlying question of the conformity of STC practices with international law remains a topical one. In June 2023, the European Council agreed on a negotiation position on the new Asylum Procedures Regulation. Under the latest[8] amended proposal for an Asylum Procedure Regulation (draft APR), the use of STC procedures shall be expanded by watering down and settling the legal safeguards of the concept on a low standard:

Article 43a(2) of the draft APR states that STC need only provide “effective protection” to refugees but they are not obligated to grant them legal status, ensure full access to healthcare, or guarantee family unity. Furthermore, the concept of “de facto-protection”, on which Article 43a(2) draft APR is based, does not comply with international refugee law. However, whether the STC must be a party to the Refugee Convention (without geographical limitation) remains, as mentioned, controversial.[9] For instance, a STC could refer to a definition of refugee different than the one laid down in the Refugee Convention, as Zimmermann argues in his dissertation. Furthermore, as a non‐contracting state, a STC could claim to not be legally bound by the principle of non‐refoulement. Lastly, there would be no possibility for the UNHCR to intervene in cases of obvious breaches of the principle of non‑refoulement. Accordingly, at least in Zimmermann’s opinion, the STC must be a party to the Refugee Convention (as well as to other human rights treaties relevant to asylum).[10] With the concept of non-refoulement becoming customary in international law and, arguably, jus cogens, the argument Zimmermann makes may have lost some of its traction. However, an expansion of the circle of STC in the sense that it is no longer required for a third country to respect the principle of non-refoulement “in accordance with the Geneva Convention”[11] would be contradictory to Article 78(1) TFEU and Article 18 of the EU-Charter which require, respectively, that the EU’s asylum policy be “in accordance” with the Refugee Convention and that “the right to asylum shall be guaranteed with due respect for the rules of the Geneva Convention”.

According to Article 45(1)(a) of the draft APR, the safety of a country is to be assessed with reference to “non-nationals”. STC could therefore include countries persecuting their own citizens and producing refugees themselves. Additionally, a third country may be categorized as a STC “with the exception of certain parts of its territory or clearly identifiable groups of persons”, Article 45(1a) draft APR. This could lead to the relocation of asylum seekers to an unstable third state, where a protection zone equivalent to the size of a refugee camp is effectively managed and asylum seekers are held there with their subsistence ensured. This raises unresolved questions regarding the EU’s responsibility for ensuring adequate living standards in third countries as well as the inclusion of asylum seekers in line with the Refugee Convention (cf. Zimmermann’s findings above).

Fortunately, the “reasonable connection requirement” is to be upheld and its definition is subject to rules under national law. This prevents EU member states from concluding a UK‑Rwanda‑like agreement and sending refugees to faraway countries with which they lack any connection. Under Article 45(2b)(b), Recital 37 of the draft APR, a reasonable connection may be established when the applicant has settled or stayed in the third country. Proposals that included references to “transit” as conclusive evidence of a connection were unsuccessful. This is in line with the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).[12] The examples provided of “settlement” and “stay” nonetheless give member states some room for interpretation in this direction. Having said that, the “reasonable connection requirement” as laid out by Zimmermann in 1994 should inform these interpretations.

Member states may presume the safety of a third country on the mere basis of an agreement between the EU and said third country as well as general assurances by that country that readmitted migrants will be “protected in accordance with the relevant international standards”, Article 45(3) draft APR. The EU-Turkey deal, however, is living proof that the mere existence of an agreement does not guarantee its safety in practice. This is why the 2007 Michigan Guidelines on Protection Elsewhere require, for permitting the referral of an asylum seeker to “protection elsewhere”, a “good faith empirical assessment”[13] by the sending state that refugees will enjoy Refugee Convention rights in the receiving state.[14] The burden of proof in this respect therefore does not lie with the asylum seeker but with the country where the asylum application was lodged, as it retains the responsibility for any action in violation of its obligations under international law, particularly the principle of non-refoulement (cf. Zimmermann’s findings above).

Conclusion and Outlook

After three years of negotiations, the European Parliament and the Council reached a political agreement on the key proposals of the Pact on 20 December 2023, including the Asylum Procedures Directive. This opened the door for further negotiations regarding technical details with a formal adoption expected before the European Parliament elections in June 2024.

The latest proposal for the APR is an example of an attempt at lowering standards with regard to the concept of STC and contradicts the EU’s endorsement of a positive contribution to the protection and promotion of human rights.[15] Once it is formally adopted (changes by means of the political agreement reached in December 2023 and further political discussions notwithstanding), refugee protection in the EU will largely depend on how member states interpret and enforce the regulation. It will be important for member states to consider the real circumstances in the third countries in question. Furthermore, due consideration should be taken of the principles of international cooperation and responsibility-sharing as expressions of international solidarity, a concept which is enshrined in the preamble of the Refugee Convention. Member states should conduct negotiations with all third countries along the migration routes and the EU should make more attractive offers of cooperation with regard to migration policy towards the relevant third countries. To this end, it should also utilize development policy instruments, for example supporting these countries in strengthening their asylum and migration policy capacities.

30 years after the German “asylum compromise”, migration remains at the forefront of the political debate. Concomitant with this is the desire of states to send asylum seekers and, by extension, responsibility to third countries. The debate about international human rights and refugee protection standards in this regard must likewise continue and it is worth bringing to attention some “old” arguments such as those put forward by Andreas Zimmermann and Jochen Frowein at the MPIL.

[1] Jochen A. Frowein, Andreas Zimmermann, Der völkerrechtliche Rahmen für die Reform des deutschen Asylrechts: Gutachten im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums der Justiz erstattet vom Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, Heidelberg, Bundesanzeiger 45 (1993).

[2] Andreas Zimmermann, Das neue Grundrecht auf Asyl – Verfassungs- und völkerrechtliche Grenzen und Voraussetzungen, Contributions on Comparative Public Law and International Law vol. 115, Heidelberg: Springer 1994.

[3] Andreas Zimmermann, ‘Asylum Law in the Federal Republic of Germany in the Context of International Law’, HJIL 53 (1993), 49-87.

[4] Translation: Christian Tomuschat et al., in cooperation with the Language Service of the German Bundestag, Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany in the revised version published in the Federal Law Gazette Part III, classification number 100-1, as last amended by the Act of 19 December 2022 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 2478).

[5] Compare: Zimmermann (fn. 2), 400-401.

[6] This is to be read against the background that, in Andreas Zimmermann’s opinion, it is required under international law that a STC is a party to the Refugee Convention.

[7] Rainer Hofmann and Tillmann Löhr, ‘Introduction to Chapter V: Requirements for Refugee Determination Procedures’ in: Andreas Zimmermann, Felix Machts and Jonas Dörschner (eds), The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol: A Commentary, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2011, 1112-1113.

[8] Any changes that were agreed upon as part of the political agreement reached in December 2023 are not expected to be available on paper until February 2014.

[9] Hofmann and Löhr (fn. 7), 1112, para 79.

[10] Compare: Zimmermann (fn. 2), 174f.

[11] Article 38(1)(c) rAPD.

[12] See CJEU, LH v. Bevándorlási és Menekültügyi Hivatal, judgement of 19 March 2020, case no. C-564/18, ECLI:EU:C:2020:218; CJEU, FMS, FNZ, SA, SA junior v. Országos Idegenrendészeti Főigazgatóság Dél-alföldi Regionális Igazgatóság, Országos Idegenrendészeti Főigazgatóság, judgement of 14 May 2020 in joint cases no. C-924/19 PPU and C-925/19 PPU, ECLI:EU:C:2020:367; CJEU, European Commission v. Hungary, judgement of 16 November 2021, case no. C-821/19, ECLI:EU:C:2021:930.

[13] Emphasis added.

[14] See also: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Guidance Note on bilateral and/or multilateral transfer arrangements of asylum-seekers, May 2013, available at: <https://www.refworld.org/docid/51af82794.html> (last accessed: 18 January 2024), para 3(iii).

|

Suggested Citation: Laura Kraft: “Asylum Compromise” Revisited, MPIL100.de, DOI: 10.17176/20240219-184505-0 |

|

| Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED | |

Laura Kraft is Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law.