Deutsch

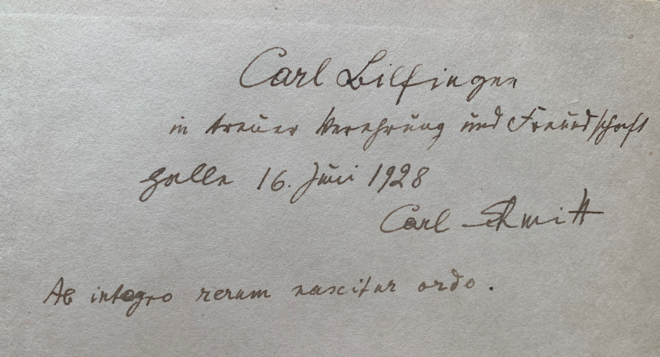

Die ministerialbürokratische Begrifflichkeit

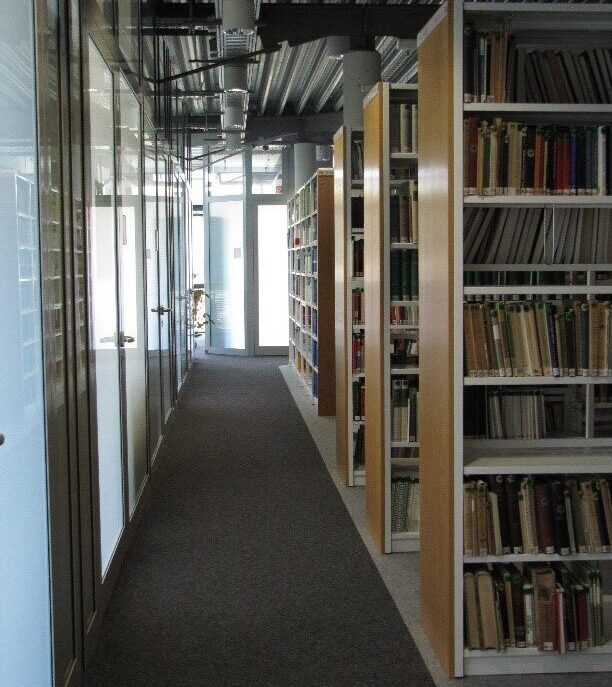

Wenn das Institut mit drei zeitübergreifenden Charakteristika beschrieben werden sollte, so wären dies erstens seine Publikationen – insbesondere die Schwarze Reihe, die trotz des sinistren Namens seit Jahrzehnten einen Leuchtpunkt im Völkerrecht setzt – und die Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht – ein Beispiel für die Unaussprechlichkeit des Deutschen in fremden Zungen; zweitens die Bibliothek, welche dieser Blog zu Recht immer wieder lobend erwähnt; und drittens die Referentenbesprechung, welche es so lange gibt wie das Institut – und die, möchte man sagen, seine conditio sine qua non bildet – eine Bedingung, welche nicht hinweggedacht werden kann, ohne dass auch das Institut entfällt. Bemerkenswert ist schon der – inzwischen muss man sagen – ursprüngliche Name: Referentenbesprechung. Denn dieser stammt nicht aus einer akademischen Nomenklatur, sondern aus dem Vokabular der Ministerialbürokratie. An der Universität gibt es Assistenten, wissenschaftliche Hilfskräfte. Referent hingegen ist ein Vortragender mit der Pflicht, sein besonderes Wissen auf einem besonderen Gebiet in die allgemeine Diskussion einzubringen, welche zu einer Entscheidungsfindung führt. Tatsächlich spricht aus dem gewählten Begriff der Geist, aus welchem das Institut entsprang: Es sollte durchaus nicht nur der „reinen Lehre“, sprich der wissenschaftlichen Forschung dienen, sondern durchaus auch in der Praxis beraten. In diesem Sinne äußerte sich schon der Gründungsdirektor Viktor Bruns. Der dritte Direktor Hermann Mosler hatte nach seiner Referentenzeit am Institut lange auch im Auswärtigen Amt gearbeitet und sah im Referentensystem des Instituts eine Spiegelung des ministerialen Organigramms.

Zum Referenten gehört natürlich ein Referat, und so wurde das Völkerrecht in Gebiete unterteilt und die Welt in Länder oder Ländergruppen, und jedes Gebiet beziehungsweise Land wurde einem Referenten zugeteilt, das dieser – manchmal nolens volens – fortlaufend beobachtete, so dass kein rechtlich relevantes Weltgeschehen sich der Aufmerksamkeit des Instituts entzog. Es gab Experten auch für entlegenere Länder oder solche mit einem schwierigeren sprachlichen Zugang – für Japan und China (in den siebziger und achtziger Jahren Robert Heuser), für die Sowjetunion (in den siebziger und achtziger Jahren Theodor Schweisfurth) oder Indien (Dieter Conrad).

Die Referentenbesprechung als Institutsinstitution

Zu den Beobachtungspflichten der Referenten traten die Berichtspflichten, das heißt es musste regelmäßig über alles Relevante berichtet werden, was sich im Bereich des jeweiligen Referates ereignete, und zwar zeitnah; die Bühne dafür bildete die wöchentliche Referentenbesprechung. Sie fand in den Anfängen des Instituts zweimal wöchentlich, nämlich dienstags und samstags, seit den fünfziger Jahren immer montags zwischen 16 und 18 Uhr statt, ein Hochamt, an dem teilzunehmen für alle wissenschaftlichen Mitarbeiter heilige Pflicht war. Ein Dispens wurde nur bei schwerwiegendsten Gründen erteilt, selbst die Direktoren teilten ihre außerinstitutionellen Aktivitäten, etwa Dienstreisen oder Sitzungen bei Organen des Europarates so ein, dass sie die Referentenbesprechung nie versäumten. Sie fiel nie aus, nur an Feiertagen und zwischen Weihnachten und Neujahr wurde einmal ausgesetzt, aber schon am 2. Januar konnte es weitergehen. Die Welt, auch die rechtliche, stand ja auch nicht still.

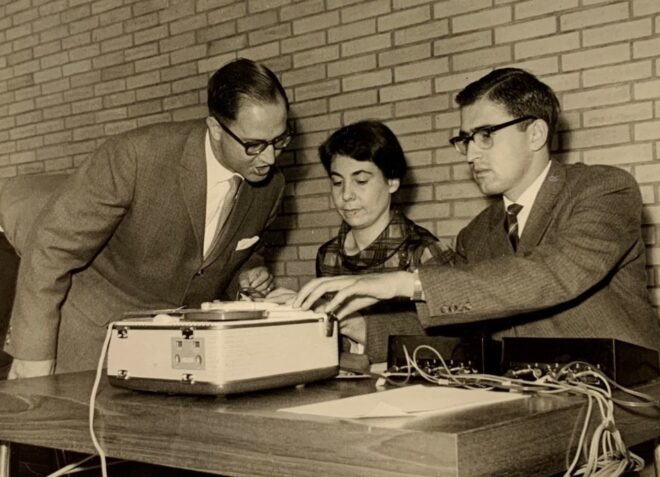

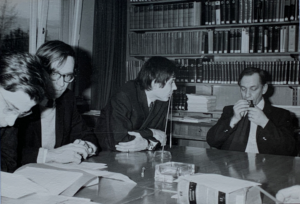

Kein Stillstand in der Welt. Fritz Münch, Günther Jaenicke und Rudolf Bernhardt (v.l.n.r.) bei der Referentenbesprechung 1972[1]

Der regelmäßige Vortrag aus dem eigenen Referat wurde erwartet, und diese Erwartung war von den Referenten so weit internalisiert, dass nur selten gesonderte Aufforderungen von Seiten der Direktoren erforderlich waren, die mit der Frage begannen: „Warum haben wir eigentlich noch nicht von diesem oder jenem Vorgang gehört?“ Dass ein jeder aus eigenem Antrieb regelmäßig berichtete, wurde als ein gebotenes Selbstverständnis vorausgesetzt. Man brauchte die Anmeldung eines Vortrags nicht Wochen vorher in einen Kalender einzutragen, ein kleiner Zettel mit Thema und Dauer konnte auch noch fünf Minuten vor Sitzungsbeginn bei der Sekretärin des sitzungsleitenden Direktors abgegeben werden.

Natürlich war der Eifer unter den Referenten nicht ganz gleichmäßig verteilt. Manche berichteten aus Liebe zum Fach oder zu sich selbst sehr häufig über das jeweilige Gebiet oder Land, auch wenn ihm in der Weltordnung nur eine geringere Bedeutung zukam. So gab es etwa den exzellenten Kenner der Türkei Christian Rumpf, der in den siebziger und achtziger Jahren so häufig zur Türkei vortrug, dass ein unbefangener Zuhörer hätte meinen können, die Türken stünden immer noch vor Wien. Besonderer Beobachtung erfreuten sich immer der Europäische Gerichtshof für Menschenrechte (EGMR) und die Europäische Menschenrechtskommission, weil das Institut mit den europäischen Organen verquickt war – durch Rudolf Bernhardt als Richter, später als Präsidenten des EGMR, und durch Jochen Abr. Frowein als Vizepräsidenten der Europäischen Menschenrechtskommission. Was in Straßburg geschah, fand in der Referentenbesprechung ein Echo.

More germanico. Ein deutscher Blick auf die Welt

Referentenbesprechung 1985. Mit: Peter Malanczuk (zweiter von links), Rainer Hofmann, Willy Wirantaprawira, Werner Meng, Torsten Stein, Karl Doehring, Otto Steiner (verdeckt), Juliane Kokott (davor), Lothar Gündling (an der Tür), Fritz Münch (vor Juliane Kokott), Matthias Herdegen (auf dem Stuhl schlafend)[2]

Die Referenten bildeten seinerzeit einen homogenen Stamm: weiß, männlich, deutsch und Volljurist. Frauen gab es wenige, Ausländer auch, die meisten von diesen arbeiteten an der Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Die Homogenität in der Zusammensetzung garantierte, dass die rechtlichen Phänomene in der Welt (nur) more germanico – nach „deutscher Methodik und Dogmatik” – untersucht und dementsprechend „fremdländische Perspektiven“ nicht eingenommen wurden. Gleichzeitig war gesichert, dass alle Referenten denselben juristischen Bildungskanon durchlaufen hatten und also auch über dasselbe solide Grundwissen, insbesondere auch im deutschen Recht verfügten. Dies machte die Verständigung einfacher, nicht alle diskutierten Fragen mussten ab ovo erklärt werden. „Amtssprache“ war Deutsch, über viele Jahre unhinterfragt; von den ausländischen Gästen, welche an der Referentenbesprechung teilnehmen und gelegentlich auch vortragen durften, wurde erwartet, dass sie des Deutschen mächtig waren oder es jedenfalls erlernten, wie dies beispielsweise bei dem späteren Präsidenten des Europäischen Gerichtshof Carlos Rodríguez Iglesias, dem späteren Präsidenten des spanischen Verfassungsgerichts Pedro Cruz Villalón oder dem ehemaligen Präsidenten des russischen Verfassungsgerichts Vladimir Tumanov der Fall war. Erst um die Jahrtausendwende wurde auf Anregung des israelischen Professors Yoram Dinstein in zwei Referentenbesprechungen im Monat auf Englisch kommuniziert.

Von der Wissensvermittlung zur Forschungsdebatte. Entwicklungslinien der Referentenbesprechung

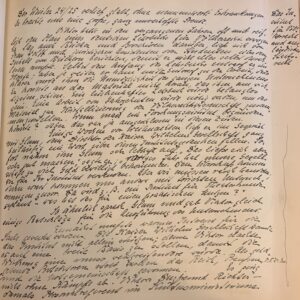

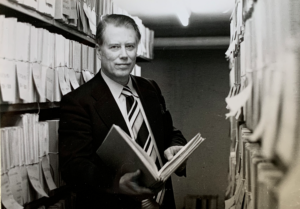

Akribisch dokumentiert. Die Protokolle der Referentenbesprechungen[3]

Anfangs, so heißt es – der Autor dieser Zeilen übersieht aus eigener Anschauung nur 40 Jahre Referentenbesprechung – war der Stil der Veranstaltung vornehmlich „ministerial“, das heißt es ging mehr um die Vermittlung von Wissen als um die Diskussion des Vermittelten. Im Wesentlichen blieb es bei den Berichten. Erst in späteren Jahren, insbesondere unter der Ägide von Professor Frowein in den achtziger Jahren, wurden die Berichte dann auch einer kritischen Diskussion durch die anderen Teilnehmer der Referentenbesprechung unterzogen. Diese Diskussion war immer zeitlich begrenzt – wie auch die Berichte selbst; es war mehr als eine lässliche Sünde, wenn die angemeldeten Zeiten für einen Bericht überschritten wurden. Spätestens wenn Professor Frowein begann, mit dem Siegelring unruhig auf den Tisch zu schlagen, war der Zeitpunkt gekommen, aus dem kunstvoll aufgebauten eigenen Gedankengebäude mit seinem überreichen intellektuellen Zierrat – bisweilen vor seiner Fertigstellung – den Notausgang zu wählen. Hier erlebte man Wittgenstein in seiner praktischen Anwendung: Was (und sei es aus Zeitgründen) nicht gesagt werden konnte, darüber musste man schweigen. Die Zeitnot in den Besprechungen rührte von dem Anspruch des Instituts, dass nichts in der Welt geschah, was der Beobachtung, Analyse und Berichterstattung im Institut entging. Das verlangte nach vielen Berichten, die bisweilen nur über jeweils fünf Minuten gingen, so dass Referentenbesprechungen mit bis zu acht Berichten durchaus keine Seltenheit waren. Das erforderte eine gewisse Flexibilität im Geist des Zuhörers beim Sprung von dem Einmarsch in Grenada über einen Schnelldurchlauf durch das deutsche Asylrecht, mit einem kleinen Zwischenstopp beim Kriegsrecht in Polen und einem Halt bei einer Entscheidung des US Supreme Court, dazu ein Blick auf ein französisches décret-loi, ein Vaterunser lang eine Bemerkungen zum neuen Codex Iuris Canonici, um schließlich, wie regelmäßig, bei der neuesten Entscheidung des EGMR zu enden. Unter der Kürze der Vorträge musste übrigens deren Qualität nicht leiden, die Begrenzung der Zeit zwang zur Präzision von Gedanken und Ausdruck. Die Anstrengung des Zuhörers bei der Vorstellung dieses Universums wurde mit dem Gefühl belohnt, zumindest einen Überblick über das juristische Weltwissen zu haben.

Politik spielte bei den Vorträgen keine Rolle, Aktivismus in juristischem Kleide war unstatthaft, nur das kühle juristische Argument zählte. Das hieß natürlich nicht, dass die meisten keine politische Überzeugungen besaßen, nur durften diese keine Grundlage für die eigenen Darlegungen bieten. Die Gegenstände waren gewissermaßen „gerichtsfest“ aufzuarbeiten, das heißt so dass man in einem streitigen Verfahren vor einem Tribunal hätte bestehen können. Wissenschaftlich wurde in der Referentenbesprechung ein Rechtspositivismus gepflegt, ohne dass die Methodik der wissenschaftlichen Untersuchung selbst Gegenstand von Betrachtungen in der Referentenbesprechung wurde. Rechtsphilosophie gehörte nicht zu den Interessenschwerpunkten, gepflegt wurde eine Dogmatik im Sinne von Kant als „das dogmatische Verfahren der reinen Vernunft, ohne vorangehende Kritik ihres eigenen Vermögens.“[4]

Nicht frei von inneren Ängsten. Diskussionskultur in der Referentenbesprechung

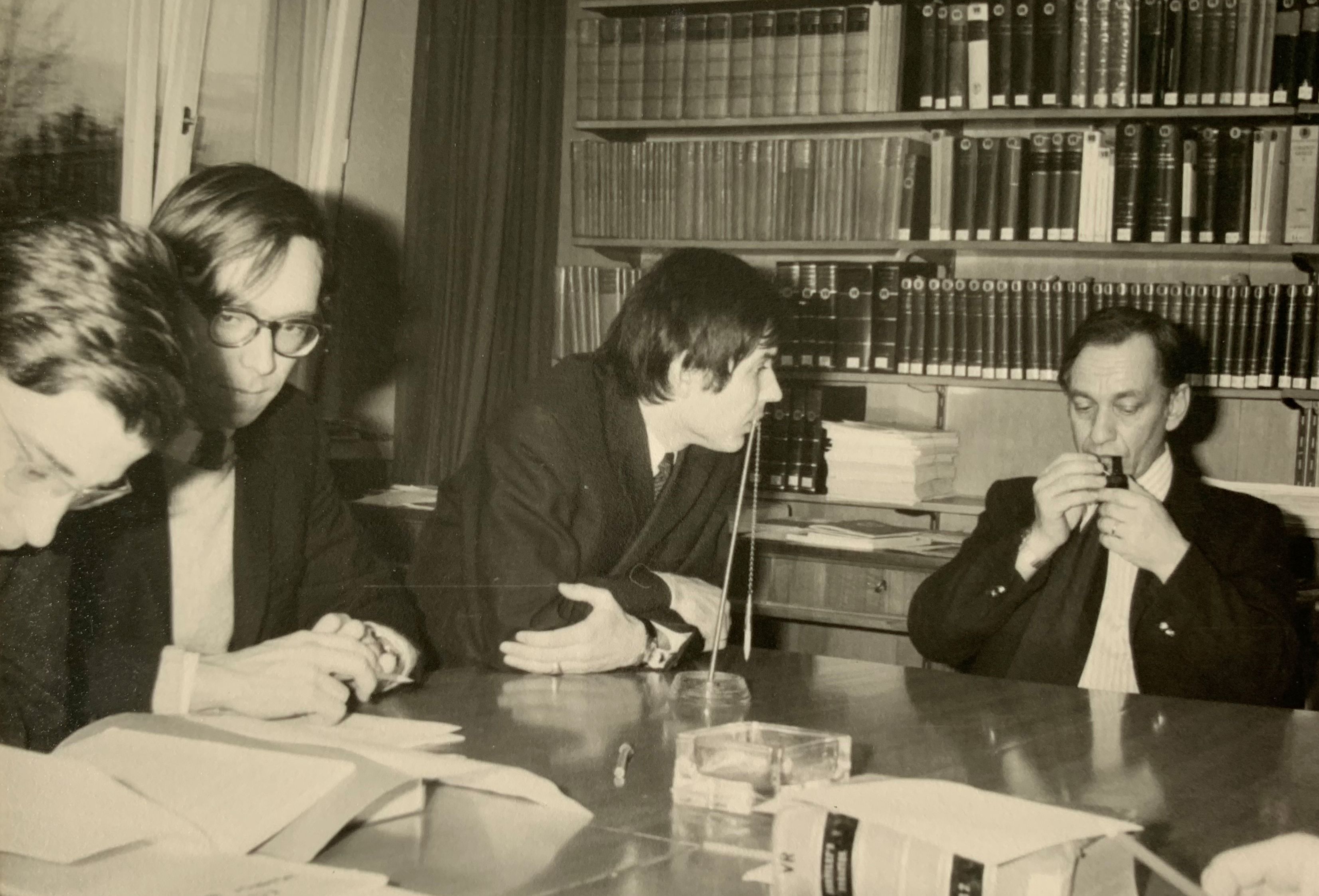

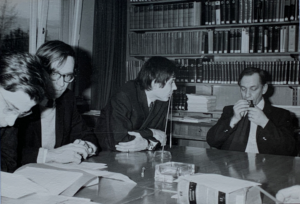

Karl Doehring (rechts) mit Kay Hailbronner (mitte) und Ernst-Ulrich Petersmann (links), 1972 bei einer Referentenbesprechung[5]

Der äußere Eindruck von der Referentenbesprechung in dem engen Besprechungszimmer im alten Institut an der Berliner Straße 48 – wo es keine feste Sitzordnung gab, aber einige Plätze inoffiziell für die Direktoren reserviert waren und frei blieben, auch wenn ein Direktor ausnahmsweise einmal abwesend war –erinnerte an ein Tabakskollegium – Professor Doehring, PD Schweisfurth und PD Stein erfüllten den Raum mit Tabakqualm (noch heute hängt er in den Büchern, die in diesem Raum vor dreißig Jahren standen). Dieser Anschein von Gemütlichkeit kontrastierte mit dem Stil der wissenschaftlichen Auseinandersetzung. Die Diskussion konnte durchaus scharfe Züge annehmen, insbesondere wenn argumentative Schwächen in der Darlegung oder eine unzureichende rechtliche oder tatbestandliche Aufklärung des Sachverhalts gewittert wurden. Mancher Vortragende sah sich unversehens in der Rolle des Angeklagten. Daher ging nicht jeder frei von inneren Ängsten in die Besprechung; sie war der „Mut-Court“ des kleinen Mannes. In der Referentenbesprechung galt wie in der Bibel: „Die Furcht des Herrn ist der Weisheit Anfang.“ Rücksicht auf etwaige Sensibilitäten wurde nicht genommen. Und wenn sich ein Referent in der rechtlichen Analyse um eine Oktave vergriffen hatte oder von Fehlvorstellungen ausging, wie ein fundierter Bericht auszusehen hat, konnte er durchaus zu einem Privatissimum – gewissermaßen einer wissenschaftlichen Nachbereitung – im Anschluss an die Referentenbesprechung in ein Direktorenzimmer gebeten werden, und das zählte zu den weniger angenehmen Erfahrungen im jungen Leben eines Referenten.

Die Anrede zwischen den Teilnehmern lautete förmlich „Herr“ bzw. „Frau” – und bei unverheirateten weiblichen Personen wie etwa bei den Referendarinnen Christine Haverland, Gerlinde Raub und Sabine Thomsen bis Anfang der achtziger Jahre auch noch – horribile dictu – „Fräulein“, durchaus ohne falschen Unterton ausgesprochen, gewissermaßen als Bezeichnung für das dritte Geschlecht, wie man es damals verstand (Dieser Anrede durften sich auch ältere unverheiratete Verwaltungs- und Biblikotheksmitarbeiterinnen, zumeist mit ihrem stillen Einverständnis, erfreuen). Die Schwingungen des neuen Zeitalters nach 1968 waren 15 Jahre später vom Institut noch nicht aufgenommen. Die Referenten duzten sich untereinander, soweit sie in derselben Alterskohorte waren, gegenüber den älteren blieb man in der Regel beim Sie. Nach Wissen des Verfassers hat Professor Mosler niemanden am Institut, auch nicht die Nachfolger im Direktorenamt geduzt, auch Professor Münch sprach alle Personen mit Sie an, und Professor Bernhardt hat sich noch bis zum Schluss, d.h. nach z.T. mehr als vierzig Jahren Zusammenarbeit auch mit seinen Co-Direktoren gesiezt.

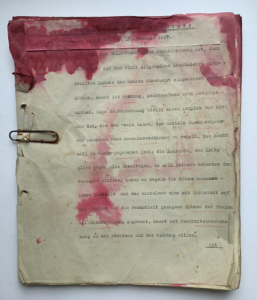

Die Referentenbesprechungen wurden protokolliert, zumeist von den jungen Hiwis, die neben dem Referendardienst einen kleinen Arbeitsvertrag am Institut hatten; dies erforderte höchste Aufmerksamkeit – gerade wegen der Diversität der Themen und wegen der Menge des zu protokollierenden Stoffes. Über die Protokolle wurde ein wesentlicher Teil der Tätigkeit des Instituts archiviert.

In der Höhle des „Löwen“: Der Institutststammtisch 1985 mit: Werner Meng, Werner Morvay, unbekannt, Dieter Conrad, Jörg Polakiewicz und Rainer Hofmann[6]

An die Referentenbesprechung schloss sich der Stammtisch an, in den achtziger Jahren im „Löwen“ in Handschuhsheim, an dem Referenten und Direktoren teilnahmen. Die Gespräche flossen freier, es wurden oft weiter juristische Themen umkreist, allerdings mit größerem Abstand, und wie es zu einem guten Stammtisch gehört, waren nun auch politische Wertungen zugelassen. Besonders ausgelassen war die Stimmung dann zu vorgerückterer Stunde, wenn nur noch die späten – und zumeist trinkfesteren – Vögel aus der Familie der Schluckspechte um den Tisch hockten; dann wurde auch das zuvor Unsagbare beim Namen genannt. In den neunziger Jahren fand diese Form der Geselligkeit immer weniger Zuspruch und kam schließlich wegen Mangel an Teilnehmern ganz zum Erliegen. Heute, wo die Öffnungszeiten der Kindertagesstätten die Uhrzeiten der Referentenbesprechung bestimmen, ist ein Stammtisch im unmittelbaren Anschluss an diese Veranstaltung undenkbar geworden. Diese Gesellschaftsform hat sich überlebt.

Internationaler und interdisziplinärer. Von der Referentenbesprechung zur Montagsrunde

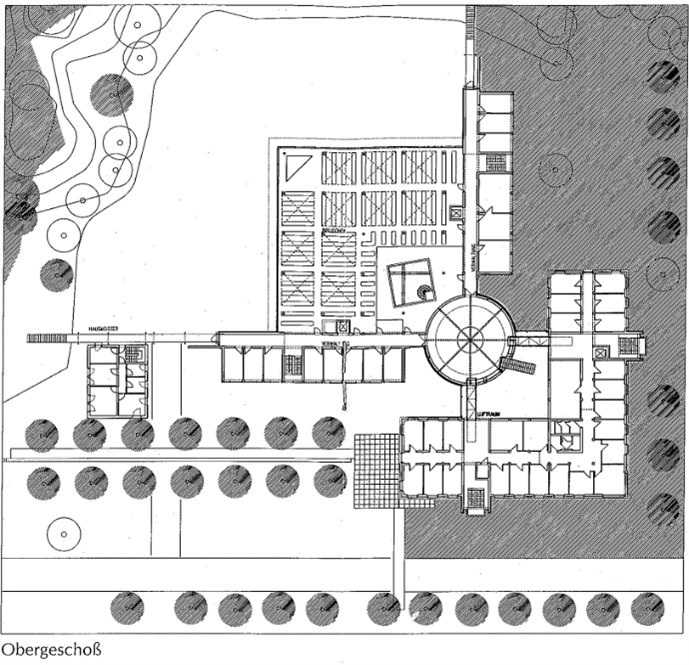

Ganz langsam änderten sich mit den Zeiten auch die Gebräuche und Gepflogenheiten in der Referentenbesprechung; mit dem Beginn der neuen Ära seit der Jahrtausendwende und bedingt durch die allgemeinen Änderungen am Institut. Das neue Institutsgebäude bietet auch für die Referentenbesprechung sehr viel mehr Platz, zuerst in Raum 014, mit seinen abstrakten großflächigen Gemälden, dann im vornehmen Raum 038, der von großen Bildschirmen für hybride Veranstaltungen dominiert wird und durch dessen Fenster man dem munteren Treiben der Hasen und Kaninchen auf der Institutswiese zuschauen kann; er lässt aufgrund seiner Deckenhöhe auch für hochfliegende Gedanken genügend Raum und jedem genug Luft zum Atmen.

Die Zusammensetzung der wissenschaftlichen Mitarbeiterschaft ist bunter geworden. Der Anteil der Frauen ist erheblich gestiegen in Richtung Parität, es werden mehr Ausländer aus aller Herren Länder eingestellt, Deutsch als Kommunikationsmittel wird in der Referentenbesprechung vom Englischen verdrängt, höchstens noch eine Besprechung im Monat findet auf Deutsch statt. Die Mitarbeiter beherrschen nicht mehr alle Deutsch. Auch haben nicht mehr alle Mitarbeiter eine deutsche Juristenausbildung, manche Mitarbeiter kommen aus der Politologie, andere aus der Philosophie, Soziologie oder Geschichtswissenschaft. Damit ändern sich die Gegenstände und das Verfahren der Untersuchungen. Methoden- und Perspektivenvielfalt, die sich in den Vorträgen in der Referentenbesprechung spiegeln, führen zu neuen Erkenntnissen und Verständnissen der rechtlichen Vorgänge in der Welt, bisweilen unter Opferung der guten alten deutschen Dogmatik und einem Anwachsen dessen, was in einem Vortrag erklärt werden muss.

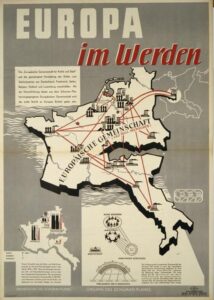

Die Referatszuteilung ist klammheimlich verschwunden, jeder darf nunmehr frei das Vortragsthema in der Referentenbesprechung wählen. Das garantiert eine Liebe des Vortragenden zum – oder jedenfalls ein originäres Interesse am – Thema. Allerdings entfällt damit auch der Anspruch des Instituts, in seiner Forschung die ganze Welt abzudecken. Manche Weltgegenden, in denen große Veränderungen vonstattengehen – wie in der arabischen Welt oder in China – sind aus dem Fokus des Interesses verschwunden und wurden wissenschaftlich gesehen zu terrae incognitae –, andere hingegen, insbesondere Südamerika haben eine zuvor nicht bestehende Aufmerksamkeit gewonnen und zahlreiche Vorträge, bisweilen sogar in spanischer Sprache, führen zu einer besonderen Expertise in dieser Region. Europa und den europäischen Ländern blieb das Institut immer treu.

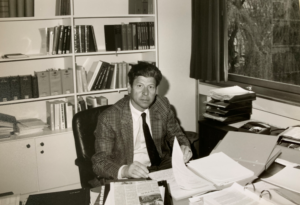

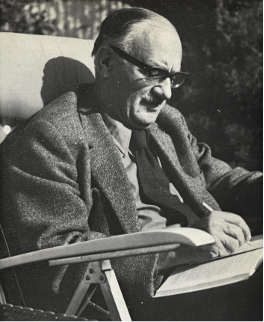

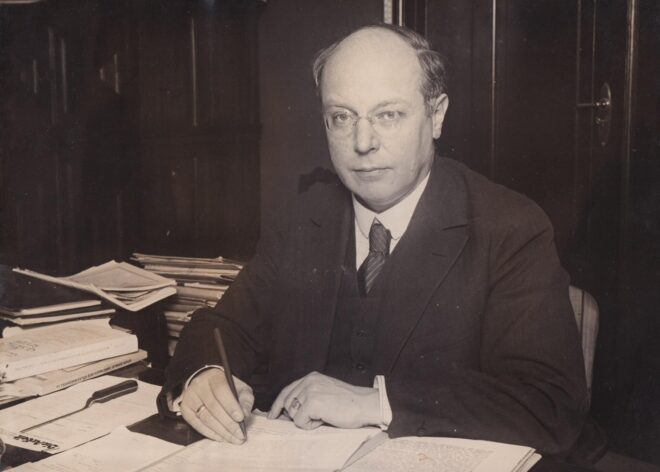

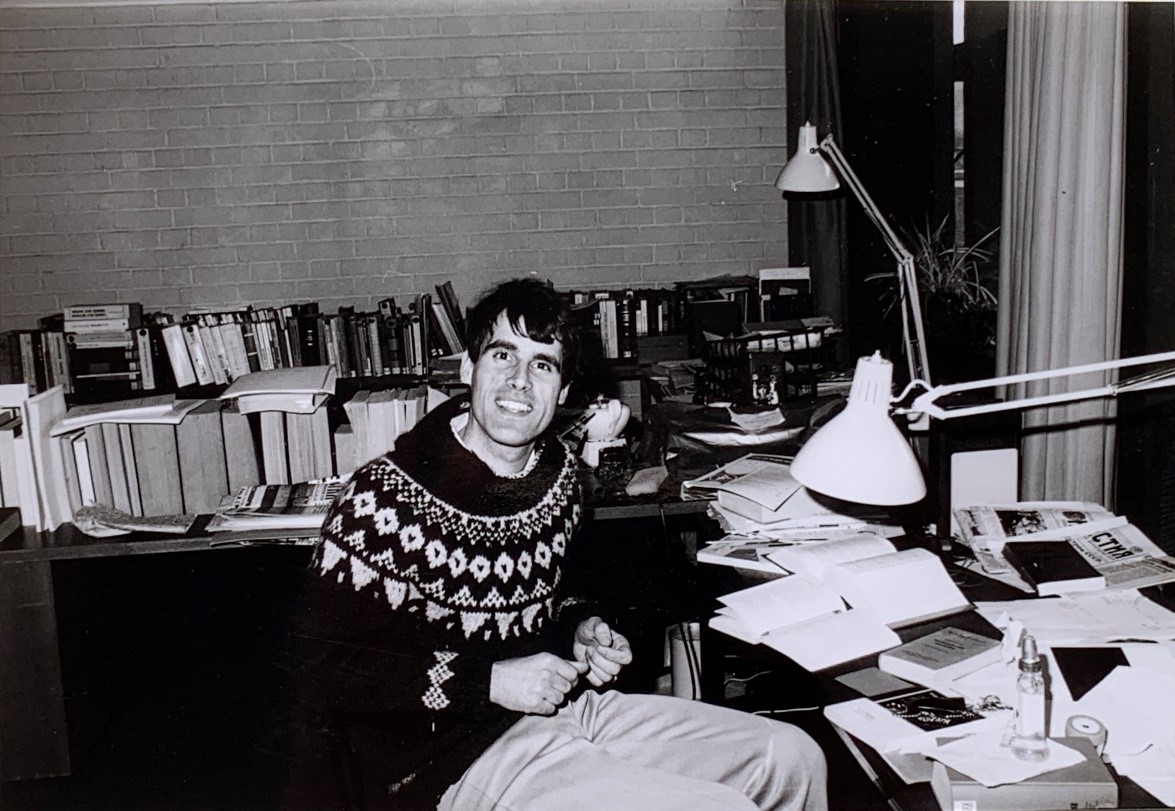

Nur 40 Jahre Referentenbesprechung. Der Verfasser in seinem Büro 1985[7]

Nur noch zwei Vorträge werden in einer Sitzung angeboten. Sie dauern jeweils bis zu einer halben Stunde, woran sich eine ebenso lange Diskussion anschließt. Dies erlaubt eine Vertiefung der Thematik und eine erschöpfende Erörterung der behandelten Frage. Auch die Darstellungsform hat sich mit der Technik gewandelt. Während in früherer Zeit allein das gesprochene Wort die Information übermittelte, finden heute Vorträge multimedial statt; in der Regel wird jeder Beitrag von einer Präsentation begleitet. Es scheint, dass mit der technischen Revolution die Kapazitäten bei der optischen Verarbeitung von Information erheblich gestiegen sind, während sie bei der akustischen entsprechend abnahmen. Protokolliert wird seit ca. 2005 nicht mehr, die Arbeit schien zu viel; stattdessen gibt es seit 2020 die Möglichkeit, den Vortrag per Video aufzeichnen zu lassen und auf Wunsch des Vortragenden ins Netz zu stellen. Damit bietet sich die Öffnung des Arcanums der Referentenbesprechung für die Welt. Es geht weniger um die Archivierung als um die Verbreitung.

Es traten äußere Lockerungen im strikten Rahmen der Referentenbesprechung ein. Früher undenkbar, ist es nun zu einer Zeitverschiebung des heiligen Termins gekommen: mit Rücksicht auf Familienpflichten und Kinderbetreuungszeiten in Kindergärten wurde die Referentenbesprechung auf 15.30 Uhr vorgezogen, dann sogar auf 14.30 Uhr. Zudem wird jetzt die Referentenbesprechung im August wegen der Urlaubszeiten ausgesetzt und schließlich wird sie nunmehr durch eine, mehr oder weniger, 15-minütige Pause in zwei Einheiten zerlegt. In den Coronazeiten Anfang der zwanziger Jahre entdeckte man das hybride Format, das die Krankheit überlebte. Jetzt weiß man vorab nicht, welchem Mitarbeiter man in Leibhaftigkeit und wem nur in virtueller Form begegnet. Damit eröffnet sich für Kollegen mit einem höheren Spezialisierungsgrad und geringerem Interesse an dem ganzen Panoptikum völker- und verfassungsrechtlicher Themen die Möglichkeit, anwesend zu wirken, aber bei Fragestellungen außerhalb des eigenen Fachgebietes unbemerkt und ungestört die eigene Spezialisierung weiter voranzutreiben.

Inzwischen rauchfrei. Die Montagsrunde 2024[8]

Insgesamt ist die Stimmung in der Besprechung lockerer und freier geworden; niemand muss mehr die Sorge hegen, in ein Kreuzverhör genommen zu werden, auch der Irrtum hat seinen Raum – jetzt im Sinne von Hegel: „Die Angst vor dem Irrtum ist der Irrtum selbst.“ Die Stimmung ist von Wohlwollen geprägt.

Die Anrede änderte sich überwiegend in die vertraulichere Nennung mit dem bloßen Vornamen, was auch den Usancen im Englischen geschuldet ist; man kann nicht in der eigenen Sprache Distanz pflegen und gleichzeitig in der Fremdsprache die Nähe suchen. Auch der Übergang zum Du über alle Generationen und Hierarchien hinweg ist keine Ausnahme mehr.

Am Ende eines Vortrags gibt es jetzt, gewissermaßen als Ausdruck des Dankes, regelmäßig Beifall. Bis weit in die erste Dekade des 21. Jahrhunderts galt es als unschicklich, auch gelungene Vorträge mit Applaus zu bedenken. Denn der Vortrag in der Referentenbesprechung war eine Dienstpflicht, und für die reine Pflichterfüllung wurde seinerzeit kein Beifall gezollt.

Summa summarum

In der Referentenbesprechung wurde über Jahrzehnte von kenntnisreichen Personen neuestes Wissen über die völker- und verfassungsrechtlichen Ereignisse in der Welt vermittelt. An keiner anderen wissenschaftlichen Einrichtung in Deutschland und wahrscheinlich in Europa erhält der interessierte Zuhörer einen solch komprimierten Überblick über die rechtlichen Vorgänge in der Welt. Sie ist das Aushängeschild für den Gegenstand und die Qualität der Arbeit am Institut, auf das gerade auch die ausländischen Gäste aufmerksam schauen.

Die Referentenbesprechung bietet zudem die Möglichkeit, die eigenen Fähigkeiten in der Vermittlung eigener Kenntnisse auszuprobieren und zu üben und dabei die eigenen Überlegungen zur Diskussion zu stellen und zu verteidigen, was zu weiteren Einsichten führen kann. In diesem Sinne ist – und war sie immer – auch eine Schule für das Leben.

Schließlich – und nicht zum Geringsten – hat die Referentenbesprechung über all die Jahrzehnte durch die regelmäßigen Treffen der Mitarbeiter für die Identitätsstiftung des Instituts eine zentrale Rolle gespielt; in dem intensiven Austausch über völker- und verfassungsrechtliche Themen bildete sich ein Esprit de Corps, der die Mitarbeiter zusammenhält und auch die Gäste mit einbezieht und zu Verbindungen führt, die auch nach der gemeinsamen Zeit am Institut fortbestehen. Dies ist ein Erfolg, der weit über die rein wissenschaftliche Erkenntnis hinausreicht.

***

[1] Foto: MPIL.

[2] Foto: MPIL, andere Personen waren nicht identifizierbar.

[3] Foto: MPIL.

[4] Immanuel Kant, Kritik der reinen Vernunft, Zweite hin und wieder verbesserte Auflage, Königsberg 1787.

[5] Foto: MPIL.

[6] Foto: MPIL; andere Personen waren nicht identifizierbar.

[7] Foto: MPIL.

[8] Foto: Maurice Weiss.

English

Reminescience of Ministerial Bureaucracy

If the Institute were to be described by three characteristics that have been common throughout its history, these would be, firstly, its publications – in particular the Schwarze Reihe, which, despite its sinister name, has been a lighthouse in international law for decades – and the Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (English title: Heidelberg Journal of International Law) – an example of the unpronounceability of German to foreign tongues; secondly, the library, which this blog rightly mentions frequently in laudatory terms; and thirdly, the Referentenbesprechung, which has been around as long as the Institute and which, one might say, forms its conditio sine qua non – a condition that cannot be dispensed with without the Institute also ceasing to exist. Its name, or, as one must put it today, its original name, alone is remarkable, for it does not come from an academic nomenclature, but from the vocabulary of ministerial bureaucracy. At university, there are research assistants and junior researchers. A Referent, on the other hand, is a speaker with the duty to contribute his or her special knowledge in a particular field to the general discussion that leads to a decision. This choice of terminology reflects the spirit from which the institute arose: it was intended to serve not just ‘pure science’, i.e. scientific research, but also to provide practical advisory. The founding director Viktor Bruns already expressed himself in this spirit. After his time as a Referent (or research fellow, as the position is called today) at the Institute, its third director Hermann Mosler had worked at the Federal Foreign Office for a long time and saw the Institute’s organisation as a reflection of the ministerial organisation chart.

Of course, each Referent needs a Referat (department), and so international law was divided up into fields and the world into countries or groups of countries, and each field and country were assigned to a research fellow who – for better or worse – continuously monitored it, so that no world event of jurisprudential relevance could escape the Institute’s attention. There were also experts for more remote countries and those access to was challenging linguistically – for Japan and China (Robert Heuser in the 1970s and 1980s), for the Soviet Union (Theodor Schweisfurth in the 1970s and 1980s), and for India (Dieter Conrad).

The Referentenbesprechung as an Institute-Institution

In addition to the Referent’s duty to observe, there was also a duty to report regularly on all relevant events in the field of the respective department, and promptly at that. The weekly Referentenbesprechung was the forum for this. In the early days of the institute, it took place twice a week, on Tuesdays and Saturdays, and since the 1950s on Mondays between 4 and 6 p.m., a High Mass that was a sacred duty for all academic staff to attend. Dispensation was only granted for the most serious reasons, and even the directors organised their non-institutional activities, such as travel or meetings with Council of Europe bodies, in such a way that they never missed the Monday Meeting. It was never cancelled, and its weekly rhythm was only disturbed by public holidays and a one-week break between Christmas and New Year but resumed on 2 January. After all, the world, including the legal world, never stood still.

The world never stands still. Fritz Münch, Günther Jaenicke, and Rudolf Bernhardt (from left to right) at a Referentenbesprechung in 1972[1]

Regular reporting from one’s own department was expected, and this expectation was internalised by researcher fellows to such an extent that explicit requests from the directors, usually in the form of the question ‘Why haven’t we heard about this or that event?’, were rarely necessary. Regular reports by each Referent on their own initiative were seen as a matter of course. One did not have to reserve time for a presentation in a calendar weeks in advance; handing a small slip of paper with the topic and duration to the secretary of the director chairing the meeting five minutes before it began sufficed. Naturally, eagerness was not distributed perfectly evenly among the researchers. Out of love for the subject or for themselves, some reported very frequently on their respective area or country, even if it was only of minor importance in the world order. There was, for example, the excellent expert on Turkey, Christian Rumpf, who spoke so frequently on Turkey in the 1970s and 1980s that an unbiased listener might have thought that the Turks were still standing at the walls of Vienna. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the European Commission of Human Rights always enjoyed special attention because the Institute was intertwined with the European institutions – through Rudolf Bernhardt as a judge, later as President of the ECtHR, and through Jochen Abr. Frowein as Vice-President of the European Commission of Human Rights. What happened in Strasbourg was echoed in the Referentenbesprechung.

More germanico. A German Outlook at the World

Referentenbesprechung 1985, with (from left to right): unidentified, Peter Malanczuk, Rainer Hofmann, Willy Wirantaprawira, Werner Meng, Torsten Stein, Karl Doehring, Otto Steiner (covered), Juliane Kokott (in front of Steiner), Lothar Gündling (next to the door), Fritz Münch (in front of Kokott), Matthias Herdegen (sleeping on his chair)[2]

The researchers formed a homogeneous tribe at the time: white, male, German and fully qualified lawyers. There were few women, and few foreigners, most of whom worked on the Encyclopedia of Public International Law. The homogeneity of the composition guaranteed that the legal phenomena in the world were analysed (only) more germanico – according to ‘German methodology and dogmatics’ – and that, accordingly, ‘foreign perspectives’ were not adopted. At the same time, it was ensured that all speakers had gone through the same legal education and therefore had the same solid basic knowledge, especially in German law. This made communication easier; not all questions had to be discussed ab ovo.

The ‘official language’ was German, unquestioned for many years; the foreign guests, who were allowed to take part in the speakers’ meeting and occasionally give presentations, were expected to speak German or at least to learn it, as was the case, for example, with the later President of the European Court of Justice Carlos Rodríguez Iglesias, or the later President of the Spanish Constitutional Court Pedro Cruz Villalón, or the former President of the Russian Constitutional Court Vladimir Tumanov. It was only at the turn of the millennium, at the suggestion of the Israeli professor Yoram Dinstein, that the Monday Meeting began to be held in English two times a month.

From the Transfer of Knowledge to a Debate of Researchers. The Development of the Referentenbesprechung

Meticulously documented. Protocols of Monday Meetings[3]

Initially, I’ve been told – the author of this contribution overlooks only 40 years of meetings from his own experience – the style of the event was primarily “ministerial”, i.e. it was more about imparting knowledge than discussing what had been imparted. The reports were at the centre. It was only in later years, particularly under the aegis of Professor Frowein in the 1980s, that the contributions were subjected to critical discussion by the other participants of the meeting. This discussion was always confined to a limited in time – as were the reports themselves; it was more than a venial sin if the time allotted for a report was exceeded. When Professor Frowein began to fretfully tap the table with his signet ring, it was high time to take the nearest exit from one’s own skilfully constructed body of thought with its abundant intellectual ornamentation – sometimes before it was completed. Here, one could experience Wittgenstein’s thought in practical application: Whereof one cannot speak (for lack of time), thereof one must be silent. The lack of time in the meetings stemmed from the Institute’s aspiration that nothing happening in the world would escape its observation, analysis and reporting. This demanded numerous reports, some of which only five minutes long, so that Monday Meetings with up to eight reports were not uncommon. Following them required a certain flexibility in the listener’s mind: The subjects went from the invasion of Grenada to a quick overview of German asylum law, with a short layover at martial law in Poland and a stop at a decision of the US Supreme Court, plus a look at a French décret-loi, a comment on the new Codex Iuris Canonici, itself taking no longer than the saying of a prayer, before the meeting concluded, as was regularly the case, with the latest decision of the ECHR. However, the brevity of the speeches did not affect their quality; the time constraints forced precision of thought and expression. The listener’s effort in following this cornucopia was rewarded with the feeling of having at least an overview of the world’s legal knowledge.

Politics played no role in the presentations, activism in legal garb was inadmissible, only the pure legal argument counted. Of course, this did not mean that most of the researchers did not have political convictions, only that presentations were not allowed to be based on them. Arguments had to be “court-proof”, i.e. presented in such a way that they could have stood up in a contentious procedure before a tribunal. Academic legal positivism was cultivated in the meetings, without the methodology of the academic enquiry itself being the subject of consideration in the Referentenbesprechung. Philosophy of Law was not an area of interest, and the dogmatic approach cultivated was in Kant’s sense “dogmatic procedure of pure reason without previous criticism of its own powers”[4].

Not Free Trepidation. Debate Culture at the Referentenbesprechung

Karl Doehring (right) with Kay Hailbronner (in the middle) and Ernst-Ulrich Petersman (left), during a Referentenbesprechung 1972[5]

There was no official seating plan for the Referentenbesprechung in the cramped conference room of the old institute building in Berliner Strasse 48, but some seats were unofficially reserved for the directors and remained empty if one of them, by exception, could not make it that day. The atmosphere was reminiscent of a gentlemen’s club – Professor Doehring, PD Schweisfurth and PD Stein filled the room with tobacco smoke (it still lingering in the books stored in this room thirty years ago). This appearance of coziness contrasted with the style of the scientific debate. The discussion could take on a sharp edge, especially when argumentative weaknesses in the presentation or insufficient legal or factual clarification of the facts were suspected. Some speakers suddenly found themselves in the role of the accused. Therefore, not everyone went into the meeting free of trepidation; they could be a proper test of courage. The Referentenbesprechung was guided by the Biblical principle: ‘The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom’. No consideration was given to any personal sensitivities. And if a speaker had gone an octave wrong in their legal analysis or had misconceptions about what constitutes a well-founded report, they could well be asked to attend a privatissimum – a kind of academic follow-up – in one of the directors’ rooms after the meeting, which was typically an unpleasant experience for the young researcher in question.

It was customary to address colleagues formally, with Herr (Mister) or Frau (Misses) – or, up until the early 1980s, in the case of unmarried women, such as legal clerks Gerlinde Raub and Sabine Thomsen, with – horribile dictu –Fräulein (Miss), which was used without questionable intentions and simply referred to a “third gender” as it was understood at the time. (This form of address was also used for older unmarried women working in the administration and the library, who rarely protested it.) The signs of a new time that had begun in 1968 could not be felt at the Institute, even 15 years later. The research fellows were on a first-name basis and used the casual Du with each other if they were in the same age cohort, but they generally kept to the formal Sie with anyone who was older. To the author’s knowledge, Professor Mosler did not address anyone at the Institute with Du, not even his successors in the directorship. Professor Münch also addressed everyone as Sie, and Professor Bernhardt, too, has always stuck to the formal ‘Sie’, even with his co-directors, and in some cases after more than forty years of collaboration.

There were protocols of the meetings, mostly written by research assistants who worked at the Institute for a couple of hours each week during their legal clerkship. Keeping track required the utmost attention, mostly because of the diversity of the topics and the amount of material to be protocoled. A significant part of the Institute’s activities was archived via these protocols.

A smoke-filled room: The Stammtisch, 1985, with: Werner Meng, Werner Morvay, unknown, Dieter Conrad, Jörg Polakiewicz, and Rainer Hofman.[6]

The Referentenbesprechung was followed by an informal get-together of research fellows and directors over drinks, a so-called Stammtisch. In the 1980s, it took place at the ‘Löwe’, not far from the Institute. Conversations flowed more freely, legal topics were often discussed further, albeit with greater distance, and, as befits a good Stammtisch, political judgements were now admissible. The atmosphere was particularly exuberant at an advanced hour, when only the those who did not mind having an extra drink or two were left at the table – then, even the previously unspeakable was called by name. In the 1990s, this form of socialising became less and less popular and eventually came to a complete standstill due to a lack of participants. Now, that the opening hours of kindergartens determine the date of the Monday Meeting, a Stammtisch immediately following this event has become unthinkable. This form of socialising has died out as times have changed.

Increasingly International and Interdisciplinary. From Referentenbesprechung to Monday Meeting

Ever so slowly, the customs and practices of the Referentenbesprechung changed, along with the times, with the beginning of a new era since the turn of the millennium and due to the general changes at the Institute. The new institute building provides much more space, including for the Monday Meetings, first in room 014, with its large abstract paintings, then in the elegant room 038, dominated by large screens for hybrid events and featuring large windows, through which one can observe the hares and rabbits in the Institute’s garden; it also leaves enough room for high-flying thoughts due to its ceiling height, and there’s plenty of air to breath for everyone.

The composition of the scientific staff has become more diverse: The proportion of women has risen considerably towards parity, more foreigners from all over the world are being recruited. German is being replaced by English in the Referentenbesprechung; today, one meeting a month is held in German, at most. Not all employees speak German anymore. Additionally, not all research fellows have a German law degree; some researchers have backgrounds in political science, others in philosophy, sociology, or history. As a result, the subject matters of their research, as well as the way they conduct it, is changing. A diversity of methods and perspectives, which is reflected in the presentations given at the Referentenbesprechung, leads to new insights and understandings of legal processes in the world, sometimes at the expense of good old German dogmatics and an increase in necessary preliminary explanations in a presentation.

The department structure has quietly disappeared; everyone is now free to choose the topic of their presentation in the Monday Meeting. This ensures that the speaker has a love for – or at least a genuine interest in – the topic. However, this also means that the Institute can no longer aspire to cover the whole world in its research. Some parts of the world where major transformations are taking place – such as in the Arab world or China – have disappeared from the focus of interest and have become academic terrae incognitae, while others, in particular South America, have gained a previously non-existent level of attention and numerous presentations, some even in Spanish, have led to particular expertise in this region. Europe and European countries have always had the Institute’s interest.

Only 40 years of Referentenbesprechung. The author in his office in 1985[7]

Now, at each session, there are only two presentations, each lasting up to half an hour, followed by an equally long discussion. This allows the subject matter to be explored in greater depth and the question at hand to be discussed exhaustingly. Furthermore, the form of presentations has changed with technology. Whereas in earlier times, researchers had to rely on the spoken word alone to convey information, a multimedia format is used today; typically, each contribution is accompanied by slides. It seems that with the technological revolution, the capacity for processing information visually has increased considerably, while the capacity for processing information acoustically has decreased accordingly. Protocols have no longer been written since around 2005, as it seemed like too much work; instead, since 2020 it has been possible to have the presentation recorded on video and, at the request of the speaker, post it online. This opens up the arcanum of the Referentenbesprechung to the world. It is less about archiving and more about dissemination.

There has been a loosening of the strict framework of the speakers’ meeting. Previously unthinkable, the sacred date of the meetings has recently changed: in consideration of family commitments and the opening hours of kindergartens, the speakers’ meeting has been preponed to 3.30 pm, later to 2.30 pm.

In addition, there are no longer any meetings during the month of August, due to holiday periods, and finally, the Monday Meeting is now divided up into two units by a, more or less, 15-minute-long break. During the Covid-19 Pandemic at the beginning of the 2020s, the hybrid format was introduced and survived the pandemic. Now, one cannot know in advance which colleagues one will meet in person and which only virtually. This opens up the possibility for colleagues with a higher degree of specialisation and less interest in the whole panopticon of international and constitutional law topics to appear to be present, but, when discussions concern questions outside their own area of expertise, quietly retreat to further advance their own specialisation, unnoticed and undisturbed.

No more smoking in the conference room. The Monday Meeting 2024[8]

Overall, the atmosphere in the meetings has become more relaxed; no one has to worry about being cross-examined, and there is room for error – now, in the sense of Hegel, “fear of erring is really the error itself”. The atmosphere is characterised by benevolence. Now, the more casual use of first names has become predominant, which is also due to the customs of the English language; one cannot maintain distance in one’s own language while establishing familiarity in a foreign language. The transition to the German ‘Du’, across all ages and hierarchies, is also no longer an exception.

Now, at the end of a presentation, there is applause – as an expression of thanks, so to speak. Until well into the first decade of the 21st century, it was considered unseemly to applaud even the most insightful presentations. After all, reporting at the Referentenbesprechung was a duty, and in those days the mere fulfilment of a duty was not considered worthy of applause.

Summa Summarum

For decades, in the Referentenbesprechung, or Monday Meeting, knowledgeable people have been imparting the latest insight into international and constitutional law in the world. No other academic institution in Germany and probably in Europe provides the interested listener with such a concise overview of legal processes worldwide. It serves to showcase the subject matters, and the quality of work conducted at the Institute, especially to foreign guests.

Furthermore, the Referentenbesprechung offers the opportunity to try out and practise one’s skills in communicating one’s knowledge and to put one’s ideas up for discussion and defend them, which can lead to further insights. In this sense, it is – and always has been – a school for life.

Last but not least, the Referentenbesprechung has played a significant role in establishing the Institute’s collective identity over the decades through the regular meetings. The intensive exchange on topics of international and constitutional law has fostered an esprit de corps that connects researchers with each other and also involves the guests, leading to connections that continue to exist even after their time together at the Institute. This is a success that goes far beyond the pursuit of purely academic knowledge.

Translation from the German original: Sarah Gebel

***

[1] Photo: MPIL.

[2] Photo: MPIL; the other persons could not be identified.

[3] Photo: MPIL.

[4] Immanuel Kant, The Critique of Pure Reason, transl. by J. M. D. Meiklejohn, 2nd ed. 1787.

[5] Photo: MPIL.

[6] Photo: MPIL.

[7] Photo: MPIL.

[8] Photo: Maurice Weiss.

Matthias Hartwig war bis 2023 Referent am Institut.