Kolorierte Postkarte des Berliner Schlosses 1913 von der Spree gesehen. Auf dieser Seite war ab 1926 das KWI für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht untergebracht (Foto: gemeinfrei)

Deutsch

Das Schwester-KWI für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht, 1933 bis 1939, mit Blick auf das KWI für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht

Was verbindet Rechtsvergleichung, Internationales Privatrecht und Völkerrecht in der NS-Zeit? Als These formuliert, verbindet die beiden juristischen Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute (KWI) der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft (KWG), dass sie keine unpolitischen oder bedingt freien Räume in der Diktatur darstellten. Sie waren in erster Linie Relais der NS-Herrschaft, nur in wenigen Hinsichten Nischen.

Dies zu untersuchen, heißt bestimmte Fragen zu stellen: Wie gestaltete sich Handlungsspielraum im Übergang zur NS-Diktatur und bei ihrer Etablierung? Wie liefen Feedback-Prozesse in den Instituten sowie zwischen Instituten, Politik und Rechtsprechung ab? Wo lagen die Grauzonen von Resilienz? Diese Fragen werden im Folgenden in den zeit- und wissenschaftsgeschichtlichen Forschungskontext eingeordnet. Im Mittelpunkt des Interesses steht, welche methodischen Erfahrungen nicht für die weitere Erforschung der Institutsgeschichte des Völkerrechts-KWI geeignet scheinen und warum nicht. Daraus ergeben sich diskussionsorientierte Thesen und Vorschläge für geeignete Aspekte einer Instituts- als exemplarischer Zeit- und Wissenschaftsgeschichte.

Der Forschungsstand, seine Lücken und blinden Flecken

Der Ausgangspunkt dieser Überlegungen ist die Beschäftigung mit dem privatrechtlichen Berliner Schwester-Institut, dem 1926 gegründeten und bis 1937 von dem Romanisten und Rechtsvergleicher Ernst Rabel (1874–1955) geleiteten Berliner KWI für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht.[1] Sie erfolgte im Rahmen des seinerzeitigen Forschungsverbundes der Präsidentenkommission der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft am Frankfurter MPI für europäische Rechtsgeschichte. Die ebenfalls in diesem Zusammenhang geplante Parallelstudie über das Schwester-KWI für Völkerrecht ist bekanntermaßen leider nicht zustande gekommen.[2]

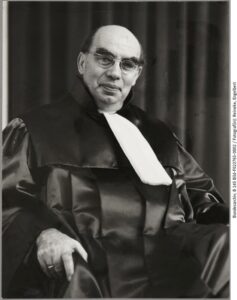

Gründungsdirektor Ernst Rabel (1874-1955) wurde 1937 aus dem Amt gedrängt (Foto: AMPG)

2007 erschienen die letzten beiden institutsgeschichtlichen Bände der MPG-Präsidentenkommission. Zum einhundertjährigen Gründungsjubiläum der KWG/MPG 2011 legten Eckart Hennig und Marion Kazemi eine 2016 Gesamtbilanz in mehreren Teilen vor.[4] Diese macht einerseits den Erkenntnisgewinn seit Beginn der intensiven Forschungsbemühungen um die Geschichte der KWG, insbesondere in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, seit den 1990er Jahren unter Rudolf Vierhaus und Bernhard vom Brocke, andererseits die noch offenen Forschungsdesiderate sichtbar. Das Institutionengefüge ist damit gut dokumentiert. Auf dieser Grundlage stellen sich allerdings erst die eigentlichen Fragen.

Die Geschichte der deutschen Großforschungs- und Wissenschaftsförderungslandschaft seit der Weimarer Republik war durch deren Relevanz für die Ermöglichungsgeschichte der NS-Herrschaft, des Zweiten Weltkriegs und Zivilisationsbruchs immer ein besonderer Bereich der Zeit- und Wissenschaftsgeschichte. Bei ihrer Erforschung kamen traditionell quellennahe investigative und stark dokumentarisch ausgerichtete historische Methoden zum Einsatz. Das führte zu einer gewissen Spannung gegenüber der, unter anderem. am Berliner MPI für Wissenschaftsgeschichte vertretenen, Richtung einer eher wissenschaftstheoretischen Wissenschafts- als Wissens- und Kulturgeschichte. Fragen nach Handlungsspielraum, Feedback und Resilienz in einem KWI in der Konsolidierungs- und Kriegsvorbereitungsphase der NS‑Diktatur haben zwar auch etwas mit Kultur und Wissen zu tun, gehen aber nicht darin auf. Das gilt insbesondere für die Rechtsgeschichte. Wenn sie von dem abgetrennt betrachtet wird, was Florian Meinel den „Möglichkeitsraum des Politischen“ genannt hat, geht ihre zeitgeschichtliche Dimension verloren. Privat- und Völkerrecht sind aber genuin politisch, insbesondere dann, wenn sie institutionengeschichtlich in einer totalitären Diktatur betrachtet werden.

Don‘ts: Die Diktatur zur Diskurs- und Wissensgeschichte machen

Diesen Weg sollte die KWI-Geschichte eher nicht gehen: den einer invasiven und theorielastigen Kulturgeschichte in der Form einer Diskurs- oder Wissensgeschichte auf dem Nenner von konstruktivistischer Kommunikation. Ernst Rabel, in seiner Bedeutung als Ausnahmewissenschaftler sicherlich mit Max Weber vergleichbar, hat das rechtsvergleichend strukturierte IPR seiner Zeit verkörpert, nicht erfunden. Seine Fähigkeit zum Überblicken des problembezogenen Lösungsvorrats ganzer Rechtssysteme hat nicht nur einen gelehrten Diskurs, sondern wesentliche Anteile des Welthandelsrechts und der internationalen Rechtsprechungspraxis direkt ermöglicht. An vielen Kodifikationen und Urteilen war Rabel beteiligt. Weder seine Leitung des Privatrechts-KWI bis 1937 noch seine Emigrationsgeschichte in den USA oder sein Remigrantenschicksal nach 1945 sind eine Redeweise. Ähnliches lässt sich über die vergleichbare Verfolgungsbiographie von Erich Kaufmann sagen. Rabel war trotz seiner Illusionen über seine Unabhängigkeit und Nützlichkeit nach 1933 ein prominentes Opfer des universalrassistischen NS-Staats. Um Ambivalenz dieser Art und Größenordnung darzustellen, braucht die KWI-Geschichte keine Reformulierung gemäß der als Zitierstandard allgegenwärtigen Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie und auch keine Wissensgeschichte des Internationalen Privatrecht oder des Völkerrechts, sondern eine Menge an einfühlender Verständnisbereitschaft. Das ist etwas anderes als Diskurstheorie oder Apologetik.

Do‘s: Umgang mit harten Akten und weichen Selbstverständnissen: Wonach sollte man suchen?

Aktenfunde aus dem Institutskeller[5]

Für eine Geschichte des Völkerrechts-KWI von der Weimarer Republik bis in die Zeit der jungen Bundesrepublik sind investigative Studien, unter anderem ausgehend vom KWG‑/MPG-Aktenbestand, zur personellen Verflechtung von juristischen Fakultäten, KWG sowie nationaler und internationaler Politik von Interesse: Wen zieht das KWI an und wo bleibt das KWI-Personal? Insbesondere für die Fragen der rechtsförmigen internationalen Politik bietet sich das bewährte methodische Instrumentarium der politischen Zeitgeschichte an, wenn es auf die Kontextualisierungsschärfe von case studies zu Personen oder Problemen staatlichen und multilateralen Handelns ankommt. Die Politikwissenschaft hat ihre Stärke im Sichtbarmachen von Strukturen von Staatlichkeit und Multilateralität, was im Unterschied zur historistischen Perspektive durch die Bereitstellung idealtypischer Verläufe und Prozesse den Vergleich ermöglicht. Mikro‑Analysen zur Publizistik, Regierungsberatung und Schiedsgerichtspraxis sollten die Relevanz- und Selbstbildkonstruktionen sowohl der Völkerrechtswissenschaft wie der Regierungspraxis berücksichtigen und mit Blick auf die zeitgeschichtliche Bedeutung der KWI-Geschichte auch für den nicht-fachjuristischen Verständnishorizont verständlich machen.

Es ist auch sinnvoll, die besondere Rolle eines KWI-Direktors am Beispiel von Viktor Bruns und seines Amtsverständnisses für das von ihm vertretene Fach darzustellen und dies in Verhältnis zum Gruppen- und Verlaufsbild der hauptamtlichen Referenten und der Entwicklung ihrer Arbeitsgebiete in Demokratie und Diktatur zu setzen. So trivial es erscheint, so hilfreich kann es dabei sein, typische Arbeitsprozesse, Ressort-Zuständigkeiten und Routinen zu rekonstruieren, um das KWI als interagierendes, reagierendes System zu verstehen, das einerseits auf bestehende wissenschaftliche, administrative und politische Strukturen gestützt ist, andererseits durch seine Tätigkeit zugleich als besonders ausgestattete und prestigereiche, international sichtbare Großforschung Einfluss auf diese nimmt. Es gab einige Mitarbeiter, die in beiden KWIs tätig waren, was die damals noch nicht ganz etablierten Fachgrenzen spiegelte: Alexander N. Makarov war ab 1928 an beiden KWIs tätig, von 1945 bis 1956 am Tübinger MPI; der überzeugte Nationalsozialist Friedrich Korkisch ab 1949 am Privatrechtsinstitut; Wilhelm Wengler ab 1935 am Privatrechts- und ab 1938 zusätzlich am Völkerrechts-KWI; Marguerite Wolff, Ehefrau von Martin Wolff, von 1924 bis 1933 als Referentin am Völkerrechtsinstitut. Die Familien Wolff und Bruns waren eng befreundet. Zudem scheint man einen gemeinsamen Mittagstisch beider Institute gehabt zu haben. Auch die Bibliothek wurde wohl geteilt.[6]

Ein Indikator für letzteres ist jedenfalls beim Privatrechts-KWI das latente Faszinations- und Spannungsverhältnis zur deutschen universitären Rechtsvergleichung und international privatrechtlichen Wissenschaft, die in Rabels Institut immer auch eine politisch stark bevorzugte, hervorragend ausgestattete Konkurrenz sah.

Wie ermöglichten Internationales Privat- und Völkerrecht Diktatur und Krieg?

Der politikgeschichtliche Leitbegriff des Handlungsspielraums zielt unter anderem seit Ludolf Herbst in der Analyse der NS-Gesellschaft darauf ab, Interaktion und Interdependenz zu rekonstruieren. Wie werden bestimmte soziale Rollen wahrgenommen? Wie verändern sie sich als professionelle Leitbilder und Tätigkeitsprofile im Übergang von der Weimarer Republik zur NS-Diktatur hinsichtlich der Selbst- und Fremddefinition? Welche Strategien der Autonomiewahrung gab es und wovon hingen sie ab? Waren sie erfolgreich und wie lange? Welches Image hatten und gestalteten sie? Wozu wurde die Autonomie genutzt oder nicht genutzt?

Eine solche Herangehensweise vermeidet eine Schwarz-Weiß-Gegenüberstellung des ideologischen NS-Herrschaftsanspruchs und der mehr oder weniger gleichgeschalteten professioneller KWI-Alltagsrealität in einem sehr spezifischen gesellschaftlichen Subsystem. Sie ermöglicht die Darstellung von Ambivalenz und Graustufigkeit, zum Beispiel im Bereich der taktischen Anpassung und bedingten Konformität.

Widerstandsgeschichte: Weniger Schwarz-Weiß, mehr Grau

Berthold von Stauffenberg (rechts) mit Frau Schmitz, Ehefrau des stellvertretenden Institutsleiters Ernst Martin Schmitz (links) auf der Betriebsfeier 1939[7]

Graustufensensibilität ist in allen NS-geschichtlichen Fragen der Gegensatz zur ahistorischen polaren Gegenüberstellung von Konformität versus Nonkonformität. Die deutsche, legitimitätsressourcenspendende Widerstandsgeschichte, vor allem verkörpert in der Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand Berlin, petrifiziert ein gleichsetzendes, moralisierendes Heldenpantheon aller Formen des deutschen Widerstands, von dem sich die Fragstellungen der kritischen Zeitgeschichte seit Jahrzehnten nicht nur entfernt, sondern distanziert haben. Da die Geschichte des Völkerrechts-KWI mit der professionellen Biographie von Berthold Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg (1905–1944) verbunden ist, stellt sich die Frage nach dem Umgang mit der Widerstandsproblematik mit besonderer Dringlichkeit. Zielführend für eine kritische Einordnung von Resilienz und Nonkonformität in bestimmten sozialen Rollen scheint eine genaue Rekonstruktion des persönlichen, professionellen und institutionellen Kontexts und der Verzicht auf jede Form der moralische Überhöhung.

Widerständig Handelnde in der NS-Diktatur entschieden sich nicht einmal und für den Widerstand, sie mussten das immer wieder und gegen wachsenden Verfolgungsdruck und um den Preis wachsender existenzieller Isolierung tun. Im Umfeld eines Widerständigen gab es Mitwissen und wegsehende Duldung, die sehr schwer quellengestützt zu fassen, aber gleichwohl Teil des Phänomens sind. Trotzdem oder gerade deshalb bleibt die Geschichte des Widerstands eine Geschichte von Einzelnen und ihren Entscheidungen, die sich nicht bequem verallgemeinern lässt. Jede übergriffige Moralisierung sagt mehr über diejenigen aus, die sie betreiben, als über die zu untersuchende Zeit. Das wird dem Ernst der Sache nicht gerecht.

Nischen und Anpassung: die Illusion der Immunität und die Realität der Diktatur

Bis heute Bestandteil der institutsinternen Erinnerungskultur: 1935 von Frank Mehnert gefertigte Büste Berthold von Stauffenbergs im Foyer des MPIL[8]

Handlungsspielraum in institutionellen Gefügen hat immer etwas mit Bedarf und Nützlichkeit zu tun. Das sind keine festen, sondern, auch in einer totalitären Diktatur, aushandlungsabhängige Größen. Hierarchien, gedachte Ordnungen und Charisma haben darauf einen Einfluss. Dass die KWG-Verwaltung den KWI-Direktor Ernst Rabel bis 1937 im Amt gehalten hat, obwohl das in Anwendung der Nürnberger ,Rasse‘-Gesetze ausgeschlossen war, ist ein Beispiel. Rabels Bleiben hing an der Protektion durch den ebenfalls 1937 von den Nationalsozialisten aus dem Amt gedrängten deutschnationalen KWG-Generaldirektor Friedrich Glum, in der sich Loyalität und Funktionalität vermischten. Rabel war aufgrund seines hohen internationalen Ansehens für Glum, aber auch für Teile der NS-Regierung, attraktiv. Vorschnelle Intentionalisierung von Handlungsspielräumen kann zu prekären Verzeichnungen einer grauen und verstrickungsreichen Wirklichkeit führen.

An den Jahrgängen 1933 bis 1937 der Zeitschrift für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht, der KWI-Institutszeitschrift, lässt sich die Verschiebung des Veröffentlichungsklimas thematisch und stilistisch gut dokumentieren. Zwar boten die verschiedenen Textgenres von thematischen Hauptartikeln, Rechtsprechungsberichten, Literaturüberblicken und Rezensionen noch ein gewisses Meinungsspektrum. Allerdings nimmt der nationalsozialistische Tenor eindeutig nicht nur zu, sondern wird bildbestimmend. Aufgrund der großen internationalen Wahrnehmung der KWI-Zeitschrift fällt es auf, wenn im Jahrgang 1935 unter anderem die „Idee des Führertums“ ein verbindendes Leitmotiv für komplexe Beiträge der Kartellrechtsregulierung abgeben soll. Rollenverteilung innerhalb der Ressorts des KWI, aber auch persönliche Präferenzen ergeben so Bild einer schiefen Ebene, an deren Ende der Versuch eines Nützlichkeitserweises für die NS-Kriegs- und Großraumwirtschaft in dem von der Wehrmacht besetzten, ausgeplünderten und terrorisierten Europa steht. „Insofern bleibt von der Vorstellung nichts übrig, das Institut habe fern der Politik ,nur‘ Fragen des Privatrechts erforscht.“[9]

[1] Rolf-Ulrich Kunze, Ernst Rabel und das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht, 1926 –1945, Göttingen: Wallstein 2004.

[2] Ingo Hueck, Die deutsche Völkerrechtswissenschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Das Berliner Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, das Hamburger Institut für Auswärtige Politik und das Kieler Institut für Internationales Recht, in: Doris Kaufmann (Hrsg.), Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Bestandaufnahme und Perspektiven der Forschung, Göttingen 2000, Bd. 2, 490-528.

[3] Foto: AMPG.

[4] Teil I: Eckart Henning/Marion Kazemi, Chronik der Kaiser-Wilhelm-/Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften 1911-2011 – Daten und Quellen, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2011; Teil II: Eckart Henning/Marion Kazemi, Handbuch zur Institutsgeschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-/ Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften 1911– 2011 – Daten und Quellen, 2 Teilbände, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2016.

[5] Foto: MPIL.

[6] Für diese Hinweise danke ich Philipp Glahé.

[7] VI. Abt., Rep. 1, Nr. KWIauslöffRechtuVölkerrecht III/37.

[8] Foto: MPIL.

[9] Michael Stolleis, Vorwort, in: Rolf-Ulrich Kunze, Ernst Rabel und das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht, 1926 –1945, Göttingen: Wallstein 2004, 9-10, 10.

Zitierte Literatur:

Rüdiger Hachtmann, Wissenschaftsmanagement im „Dritten Reich“. Geschichte der Generalverwaltung der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, 2 Bände, Göttingen: Wallstein 2007.

Helmut Maier, Forschung als Waffe. Rüstungsforschung in der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft und das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Metallforschung, 2 Bände, Göttingen: Wallstein 2007.

Rolf-Ulrich Kunze, Die Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes seit 1925. Zur Geschichte der Hochbegabtenförderung in Deutschland, Berlin: Akademie Verlag 2001.

Florian Meinel, Vertrauensfrage. Zur Krise des heutigen Parlamentarismus, München: C.H. Beck 2019.

Ludolf Herbst, Deutschland 1933–1945. Die Entfesselung der Gewalt: Rassismus und Krieg, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1996.

English

The “Sister” KWI for Comparative and International Private Law, 1933 to 1939, with a View to the KWI for Comparative Public Law and International Law

What is the connecting element of comparative law, private international law and international law in the Nazi era? Laid out as a thesis, the two juridical Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes (Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute, KWI) of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, KWG) are comparable insofar that they did not represent apolitical or conditionally free spaces in the National Socialist dictatorship. They were primarily relays of Nazi rule, niches only in a few respects.

Investigating this means asking certain questions: What room for manoeuvre existed during the transition to the Nazi dictatorship and during its establishment? How did feedback processes take place within the institutes and between them, polity, and jurisdiction? Where lay the grey areas of resilience? In the following, these questions are embedded within the research context of contemporary history and history of science. The focus of interest is on which methodological experiences do not seem suitable for further research into the history of the International Law KWI and why not. From that, discussion-orientated theses and suggestions for apt aspects of an institute history as an exemplary contemporary and academic history are derived.

The State of Research, its Gaps and Blind Spots

The starting point for these considerations is the study of the Berlin “sister” institute, the KWI for Comparative and International Private Law[1], which was founded in 1926 and, until 1937, led by the romanicist and comparative law scholar Ernst Rabel (1874-1955). It was carried out in the context of the research network of the Max Planck Society’s Presidential Commission on the History of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society at the Frankfurt MPI for Legal History. A complimentary study on the “sister” institute for international law, which was also planned in this context, was unfortunately never conducted.[2]

Founding director Ernst Rabel (1874-1955) was forced out of office in 1937 (Photo: AMPG)

The last two of the MPG Presidential Commission volumes on the history of the institute were published in 2007. Commemorating the centenary of the founding of the KWG/MPG in 2011, Eckart Hennig and Marion Kazemi presented an overall assessment in several parts in 2016.[4] On the one hand, this highlights the knowledge gained since the beginning of the intensive research endeavour into the history of the KWG, particularly during the National Socialist era, since the 1990s under Rudolf Vierhaus and Bernhard vom Brocke, yet also the remaining research desiderata. The institutional structure is already well documented. However, it is only on this basis that the real questions arise.

The history of the German large-scale research and science funding landscape since the Weimar Republic has, due to its relevance for the historical pathway towards National Socialism, the Second World War and the Shoah, always been a peculiar area of contemporary history and the history of science. Traditionally, in researching it, investigative source-based and historical methods with a strong documentary focus were used. This led to a certain amount of tension with a more epistemological approach of a history of science as a history of knowledge and culture, as represented, among others, at the Berlin MPI for the History of Science. Questions about room for manoeuvre, feedback and resilience in a KWI in the consolidation and war preparation phase of the National Socialist dictatorship are linked to culture and knowledge but there are additional aspects to be covered. This applies in particular to legal history. If it is considered separately from what Florian Meinel has called the “realm of possibility of the political”, its historical dimension is lost. Private and international law, however, are genuinely political, especially when they are viewed from the perspective of institutional history in a totalitarian dictatorship.

Don’ts: Turning Dictatorship into a History of Discourse and Knowledge

This is the path KWI history should avoid: an invasive and mostly theoretical cultural history in the form of a history of discourse or knowledge based on the denominator of constructivist communication. Ernst Rabel, in his significance as an exceptional scholar certainly comparable to Max Weber, embodied, but did not invent, the comparative legal structuring of IPR of his time. His ability to survey the problem-related reservoir of solutions offered by entire legal systems not only facilitated a scholarly discourse, but also directly facilitated significant parts of world trade law and international legal practice. Rabel was involved in many codifications and judgements. Neither his leadership of the Private Law Institute until 1937 nor his history of emigration to the USA and his fate as a re-migrant after 1945 are a mere talking point. The same can be said about Erich Kaufmann’s comparable biography of persecution. Despite his illusions about his independence and usefulness after 1933, Rabel was a prominent victim of the universally racist National Socialist state. In order to portray ambivalence of this kind and magnitude, KWI history does not need a reformulation according to the actor-network theory ubiquitous as a citation standard, nor a history of knowledge of private international law or international law, but rather a great deal of empathetic understanding. This is different from discourse theory or apologetics.

Do’s: Dealing with Hard Files and Soft Self-Image: What Should You Look for?

Files found in the institute’s basement[5]

For a history of the International Law KWI from the Weimar Republic to the age of the young Federal Republic of Germany, investigative studies on the personal entanglements between law faculties, the KWG and national and international politics, based, among others things, on the KWG/MPG files are of interest: Who does the KWI attract and where does the KWI staff end up? Especially for questions of law-based international politics, the tried-and-tested methodological instruments of contemporary political history are useful, when the sharp contextualization offered by case studies on individuals or problems of state and multilateral action is needed. Political science has its strength in making structures of statehood and multilateralism visible, which, in contrast to the historicist perspective, enables comparison by pointing out archetypical trajectories and processes. Micro analyses of publications, political advisory, and the practice of Arbitral Tribunals should take into account the constructions of relevance and self-image of both international law scholarship and government practice and, with a view to the historical significance of KWI history, also make them comprehensible for lawyers outside of the field.

Furthermore, it is advantageous to illustrate the special role of a KWI director using the example of Viktor Bruns and his understanding of his role for the field he represented, and to relate this to the collective self-image and development of full-time research fellows and the development of their fields of work in democracy and dictatorship. As trivial as it may seem, it can be helpful to reconstruct typical work processes, departmental responsibilities and routines in order to understand the KWI as an interacting, reacting system, which on the one hand is based on existing scientific, administrative and political structures and at the same time influences them through its activities as a specially equipped and prestigious, internationally visible large-scale research organisation. Some persons worked at both KWIs, reflecting the disciplinary boundaries not yet being fully established at the time: Alexander N. Makarov worked at both KWIs from 1928 and from 1945 to 1956 at the Tübingen MPI; the staunch National Socialist Friedrich Korkisch was employed at the Private Law Institute from 1949; Wilhelm Wengler, from 1935 at the Private Law Institute and from 1938 additionally at the International Law Institute; Marguerite Wolff, wife of Martin Wolff, was a research fellow at the International Law Institute from 1924 to 1933. The Wolff and Bruns families were close friends. The staff of the two institutes also seem to have had lunch together. Likely, the library was also shared.[6]

One indicator of the latter is, at least for the Private Law Institute, the relationship of latent fascination and tension with comparative law research conducted at German universities and international private law scholarship, which always saw Rabel’s institute as a politically favoured, excellently equipped competitor.

How Did International Private Law and International Law Enable Dictatorship and War?

The political-history category of room for manoeuvre in the analysis of society under National Socialism, aims, since Ludolf Herbst, among other things, at guiding the analysis of interactions and interdependences. How are certain social roles perceived? How do they change as professional ideals and profiles in the transition from the Weimar Republic to the Nazi dictatorship in terms of self-definition and perception? What strategies existed for maintaining autonomy and what did they depend on? Were they successful and for how long? What image did they have and what image did they create? Where did actors make use of their autonomy and where did they fail to do so?

Such an approach avoids a black-and-white juxtaposition of the ideological claim to power of National Socialism and the more or less intense effect of Gleichschaltung on the professional everyday reality at the KWI in a very specific social subsystem. It enables the depiction of ambivalence and shades of grey, e.g. in the area of strategic and conditional conformity.

History of Resistance: Less Black and White, More Grey

Berthold von Stauffenberg (right) with Ms Schmitz, wife of the institute’s deputy director Martin Schmitz, (left) at the office party in 1939[7]

Sensitivity towards the existence of shades of grey is, in all questions concerning the history of National Socialism, the antithesis to the ahistorical idea of a polar opposition of conformity and non-conformity. The history of German resistance, providing resources for legitimacy and embodied above all in the German Resistance Memorial Centre in Berlin, petrifies an equating, moralising pantheon of heroes of all forms of German resistance. The research questions of critical contemporary history have not only departed but distanced themselves from this perspective in the last decades. As the history of the International Law Institute is linked to the professional biography of Berthold Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg (1905-1944), the question of how to deal with the issue of resistance is particularly urgent. For a critical assessment of resilience and non-conformity in certain social roles, a precise reconstruction of the personal, professional and institutional contexts and the renunciation of any form of moral exaggeration seems to be expedient.

Members of the resistance against the National Socialist dictatorship did not make a one-time decision; they took a stance repeatedly, despite a growing danger of persecution and at the cost of increasing existential isolation. In their environment, complicity and intentional ignorance existed, both of which are very difficult to grasp on the basis of source material but are nevertheless part of the phenomenon. Despite or precisely because of this, the history of resistance remains a history of individuals and their decisions, which cannot be conveniently generalised. Any encroaching attempt at moralisation says more about those who engage in it than about the subject of historical investigation. It does not do justice to the seriousness of the matter.

Niches and Adaptation: The Illusion of Immunity and the Reality of Dictatorship

Part of the institute’s internal culture of remembrance to this day: Bust of Berthold von Stauffenberg made by Frank Mehnert in 1935 in the foyer of the MPIL[8]

Room for manoeuvre in institutional structures is generally interrelated with demand and usefulness. These attributes are not static, but based on negotiation, even in a totalitarian dictatorship. This process is influenced by hierarchies, perceived orders, and charisma. The fact that the KWG administration kept KWI director Ernst Rabel in office until 1937, despite this being non-compliant with the Nuremberg Laws, is one example. Rabel’s retention depended on the protection, resulting from a combination of loyalty and pragmatism, of the KWG Director General Friedrich Glum, a nationalist who, too, was forced out of office by the National Socialists in 1937. Rabel’s outstanding international reputation made him attractive to Glum, but also to parts of the National Socialist government. The premature construction of intentionality regarding the exertion of room for manoeuvre can lead to precarious distortions of a multifaceted and entangled reality.

The 1933 to 1937 issues of the Zeitschrift für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht (Today: Rabels Zeitschrift für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht / The Rabel Journal of Comparative and International Private Law), the KWI’s institute journal, lend themselves to the documentation of the shift in publishing climate, both thematically and stylistically. The thematic main articles, across various text genres like case law reports, literature overviews and reviews did still offer a certain spectrum of opinions; however, the National Socialist tenor was clearly not only increasing but becoming dominant. Due to the high international profile of the KWI journal, it is striking that in 1935, among other things, the “idea of Führertum” is presented as a unifying theme for complex articles on the legal regulation of cartels. The distribution of roles within the departments of the KWI, but also personal preferences, thus paint a picture of a diverted playing-field, escalating to an attempt to demonstrate usefulness for the National Socialist economy oriented towards war and Großraum in a Europe, plundered and terrorised by the occupying Wehrmacht. “Insofar, nothing remains of the idea that the institute, far removed from politics, ‘only’ researched questions of private law.”[9]

Translation from the German original: Sarah Gebel

[1] Rolf-Ulrich Kunze, Ernst Rabel und das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht, 1926 –1945, Göttingen: Wallstein 2004.

[2] Ingo Hueck, Die deutsche Völkerrechtswissenschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Das Berliner Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, das Hamburger Institut für Auswärtige Politik und das Kieler Institut für Internationales Recht, in: Doris Kaufmann (ed.), Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Bestandaufnahme und Perspektiven der Forschung, Göttingen: Wallstein 2000, vol. 2, 490-528.

[3] Photo: AMPG.

[4] Part I: Eckart Henning/Marion Kazemi, Chronik der Kaiser-Wilhelm-/Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften 1911-2011 – Daten und Quellen, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2011; Part II: Eckart Henning/Marion Kazemi, Handbuch zur Institutsgeschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-/ Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften 1911– 2011 – Daten und Quellen, 2 Volumes, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2016.

[5] Photo: MPIL.

[6] I would like to thank Philipp Glahé for this information.

[7] Photo: VI. Abt., Rep. 1, Nr. KWIauslöffRechtuVölkerrecht III/37.

[8] Photo: MPIL.

[9] Michael Stolleis, Vorwort [Preface], in: Rolf-Ulrich Kunze, Ernst Rabel und das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht, 1926 –1945, Göttingen: Wallstein 2004, 9-10, 10.

Literature cited:

Rüdiger Hachtmann, Wissenschaftsmanagement im „Dritten Reich“. Geschichte der Generalverwaltung der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, 2 Volumes, Göttingen: Wallstein 2007.

Helmut Maier, Forschung als Waffe. Rüstungsforschung in der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft und das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Metallforschung, 2 Volumes, Göttingen: Wallstein 2007.

Rolf-Ulrich Kunze, Die Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes seit 1925. Zur Geschichte der Hochbegabtenförderung in Deutschland, Berlin: Akademie Verlag 2001.

Florian Meinel, Vertrauensfrage. Zur Krise des heutigen Parlamentarismus, München: C.H. Beck 2019.

Ludolf Herbst, Deutschland 1933–1945. Die Entfesselung der Gewalt: Rassismus und Krieg, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1996.

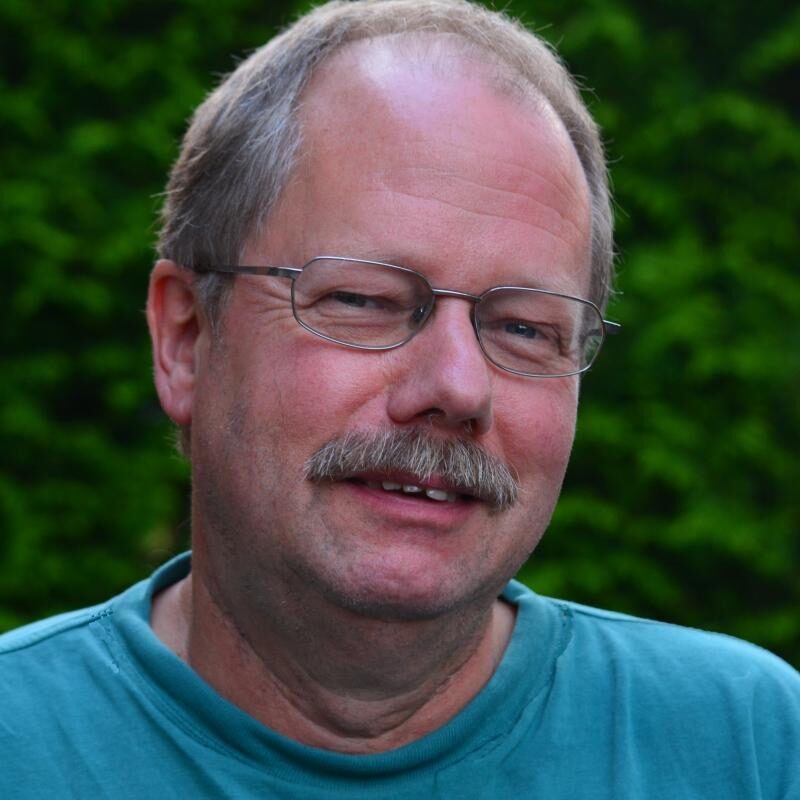

Rolf-Ulrich Kunze ist Professor für Neuere und neueste Geschichte am Department für Geschichte des Karlsruher Instituts für Technologie (KIT).

Rolf-Ulrich Kunze is Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at the Department of History at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT).