Deutsch

Was war das Institut für Besatzungsfragen?

Der frühere Sitz des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen in der Stauffenbergstraße 32 in Tübingen[1]

Im Oktober 1947 wurde auf Betreiben des damaligen Justizministers und Stellvertreters des Staatspräsidenten, Carlo Schmid,[2] in der Staatskanzlei Württemberg-Hohenzollern ein „Referat für Verfassungs- und Besatzungsfragen“ eingerichtet. Anfang 1949 ging aus diesem Referat das Institut für Besatzungsfragen hervor, das 1950 eine Villa in der Stauffenbergstraße 32 auf dem Tübinger Österberg bezog. Formell war das Institut eine politisch unabhängige Einrichtung mit wissenschaftlichem Anspruch. Faktisch aber erfüllte es eine beratende und zuarbeitende Funktion für die württembergische Landesregierung. Bald schon weitete sich sein Blick auf alle drei westlichen Besatzungszonen. Seine erklärte Absicht war es, die Einwirkungen der Besatzungsmächte auf Deutschland zu dokumentieren, einen systematischen Überblick über besatzungsrechtliche Vorschriften zu schaffen und Besatzungslasten beziehungsweise -schäden finanziell zu beziffern.[3] Neben Publikationen zum Besatzungsrecht und zur Besatzungspraxis erstellte das Institut Rechtsgutachten für politische Institutionen und private beziehungsweise privatwirtschaftliche Akteure. Zwischen dem Institut für Besatzungsfragen und dem Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut (KWI) beziehungsweise dem Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (MPIL) bestanden zahlreiche inhaltliche wie personelle Schnittpunkte. Aus diesem Grund lagert seit seiner Auflösung 1960 ein großer Bestand der Unterlagen des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen im Bibliotheksmagazin des MPIL.

Leiter des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen wurde der Jurist Gustav von Schmoller (1907–1991). Schmoller stammte aus einer preußischen Offiziersfamilie und war Enkel des gleichnamigen Nationalökonomen und Historikers. Er hatte von 1925 bis 1929 unter anderem in Tübingen bei Carlo Schmid studiert, der 1928 Referent am Berliner KWI gewesen war und sich dort mit Reparations- und Restitutionsfragen aus dem Versailler Vertrag befasst hatte. Schmoller war im Mai 1933 in die NSDAP eingetreten. Ab Mai 1934 arbeitete er für einige Monate in Berlin als Assistent von Carl Schmitt, der 1933 als wissenschaftliches Mitglied in das KWI aufgenommen worden war. Offenbar war Schmoller eng eingebunden in die Entstehung des Aufsatzes Der Führer schützt das Recht,[4] mit dem Schmitt dem Vorgehen Hitlers im Zuge des sogenannten Röhm-Putschs eine juristische Absolution erteilte. 1935 wurde Schmoller Referent im Reichswirtschaftsministerium. Nach einer Zwischenstation in der freien Wirtschaft war er von November 1939 an auf wechselnden Positionen in der deutschen Protektoratsverwaltung für Böhmen und Mähren tätig.[5] 1941 verteidigte er seine von Schmitt betreute Dissertation über Großraumordnung und Neutralität.[6] Zweitgutachter der Arbeit war Viktor Bruns, der damalige Leiter des KWI für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht.

Schon kurz nach Kriegsende wurde Schmoller einer der engsten Berater von Carlo Schmid, der als Vertrauensperson der französischen Besatzungsmacht und Mitglied der wiedergegründeten SPD einer der tonangebenden Akteure für den Wiederaufbau des politischen Lebens in Tübingen und Württemberg-Hohenzollern war. Unter anderem ließ sich Schmid im August 1948 von Schmoller zum Verfassungskonvent auf Herrenchiemsee begleiten. Schmids Memoiren zufolge hatte Schmoller „hervorragenden Anteil an der Abfassung der Denkschrift […], in der Arbeitsweise und Beratungsergebnis des Konvents festgehalten wurden.“[7] Gestützt auf die Ressourcen des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen übernahm Schmoller außerdem eine wichtige Rolle bei der Aushandlung, Auslegung und Revision des Besatzungsstatuts, das die Beziehungen zwischen der Bundesrepublik und den drei westlichen Besatzungsmächten regelte.[8] Im Herbst 1952 trat Schmoller in den Auswärtigen Dienst ein. Nach Stationen in der Bonner Zentrale, als Botschaftsrat in Athen und als Generalkonsul in Istanbul wurde er 1965 Botschafter der Bundesrepublik in Stockholm.

Die Leitung des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen übernahmen nun die Juristin Hedwig Maier und der Volkswirt Achim Tobler. Ebenso wie Schmoller hatte auch der Deutsch-Schweizer Tobler eine „braune“ Vergangenheit. 1933 war er in die SS eingetreten, seit 1939 sogar für den Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers SS tätig. 1935 hatte er bei Arnold Bergstraesser in Heidelberg promoviert.[9] Hedwig Maier (geb. Reimer) hingegen fiel biografisch aus der Reihe. Sie hatte Anfang der 1930er Jahre als eine der ersten Frauen überhaupt an der Universität Berlin in Jura promoviert und eine Anstellung im juristischen Staatsdienst gefunden. Erst Mitte der 1930er Jahre musste sie ihre Stelle infolge der frauenfeindlichen Politik der Nationalsozialisten aufgeben. 1937 heiratete sie den Juristen Georg Maier, der wiederholt mit dem NS-Regime in Konflikt geraten war, 1939 zur Wehrmacht eingezogen wurde und im Oktober 1945 in sowjetischer Kriegsgefangenschaft starb. Nach dem Krieg ließ sie sich Maier mit ihren vier Kindern in Tübingen nieder. Im Rahmen des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen nahm sie ihre juristische Tätigkeit wieder auf. Bald wurde sie Richterin und schließlich sogar Direktorin des Tübinger Landgerichts.[10]

In der Hochphase beschäftigte das Institut für Besatzungsfragen sechzehn feste Mitarbeiter:innen und zehn Hilfskräfte. In Kooperation mit der Universität Tübingen entstanden mehrere Promotionen, die dann vom Institut publiziert wurden. Dass die Arbeiten des Instituts für politisch bedeutsam und nützlich gehalten wurden, zeigt sich an seiner Finanzierung. Das Land Württemberg-Hohenzollern stellte jährlich 20.000 DM zur Verfügung. 1949 kam das Land Württemberg-Baden als weiterer Geldgeber hinzu. Seit 1950 beteiligten sich auch alle übrigen Bundesländer mit einem Jahresbeitrag von 10.000 DM. 1951 übernahm der Bund die Grundfinanzierung. Von 1954 an bis zu seiner Auflösung 1960 finanzierte sich das Institut dann offenbar vollständig selbst aus Spenden, dem Verkauf von Publikationen und Honoraren für Gutachten und Vorträge.[11]

Quellen und Forschungsstand

Aktenbestände des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen im Bibliotheksarchiv des MPIL[12]

Nach Einstellung seiner Arbeit übergab das Institut seine Unterlagen inklusive seiner Bibliothek und seiner umfangreichen Sachkartei an das MPIL, mit dem es schon vorher intensiv kommuniziert und kooperiert hatte. Die inhaltlichen Schnittmengen beider Einrichtungen waren groß. Auch das MPIL setzte sich in seiner Forschung und gutachterlichen Tätigkeit intensiv mit besatzungsrechtlichen Fragen auseinander, wobei vielfach Parallelen zur Situation Deutschlands nach dem verlorenen Ersten Weltkrieg und zur Rolle des Berliner KWI bei der Durchsetzung deutscher Rechtsstandpunkte gezogen wurden. Insbesondere die bis 1960 in Berlin bestehende Abteilung des Instituts befasste sich mit ,Kriegsfolgenforschung‘, worunter insbesondere Fragen zum rechtlichen Status von Berlin und zur Sowjetischen Besatzungszone, Fragen der Staatsangehörigkeit, Besatzungskosten, Kriegs- und Besatzungsschäden oder die Oder-Neiße-Linie fielen.[13] Als mit dem Deutschlandvertrag 1952 das Besatzungsstatut aufgehoben wurde und die Auflösung des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen im Raum stand, zeigten das MPIL und sein Direktor Carl Bilfinger beziehungsweise sein Nachfolger Hermann Mosler großes Interesse an dessen Aktenbeständen.[14] Hermann Mosler hatte bereits 1945 mit Richard Thoma und Ernst Friesenhahn an der Universität Bonn eine Beratungsstelle für Völker- und Besatzungsrecht eingerichtet und sich in der Folge unter anderem als Gutachter im Nürnberger Krupp-Prozess 1947/48 als vehementer Gegner der alliierten Demontage-Politik profiliert.[15]

Das MPIL wiederum gab einen Großteil des vom Institut für Besatzungsfragen überlassenen Materials 1970 an das Bundesarchiv Koblenz[16] sowie das Staatsarchiv Sigmaringen[17] ab. Ein Teil der Rechtsgutachten lagert jedoch bis heute im Magazin des MPIL in Heidelberg. Ergänzende Archivquellen finden sich in Beständen vormaliger Kooperationspartner und in Nachlässen ehemaliger Mitarbeiter:innen. Hinterlassen hat das Institut außerdem eine Vielzahl an Publikationen zur Besatzungspolitik der Alliierten in Deutschland[18] sowie eine zwanzigbändige Schriftenreihe zur deutschen Besatzungspolitik in Europa während des Zweiten Weltkriegs.[19] Ergebnisse der Institutsarbeit flossen außerdem in Aufsätze und Monografien von Mitarbeiter:innen ein.[20]

Angesichts der hervorragenden Quellenlage erstaunt es, dass das eng mit der Besatzungszeit und der Gründungsgeschichte der Bundesrepublik verflochtene Wirken des Instituts in der historischen Forschung bislang praktisch keine Beachtung gefunden hat. Einen Überblick zur Institutsgeschichte geben zwei Aufsätze von Schmoller, die als Zeitzeugenberichte aber keine neutrale Perspektive einnehmen.[21] Dirk Blasius hat sich kritisch mit Schmollers Biografie und seiner Beziehung zu Carl Schmitt befasst.[22] Das Institut für Besatzungsfragen erwähnt er aber nur am Rande. Unser Wissen über das Personal und die Aktivitäten des Instituts, über die Inhalte seiner Publikationen und Gutachten, über seinen politischen Einfluss und seine gesellschaftliche Resonanz ist – gut 75 Jahre nach seiner Gründung und 65 Jahre nach seiner Auflösung – äußerst gering. Über seine Wahrnehmung durch die Besatzungsmächte ist bis heute nichts bekannt.

Thesen zur historischen Bedeutung des Instituts

Karte der Besatzungszonen in Deutschland, 1945[23]

Dieser unbefriedigende Forschungsstand verwundert, war Institut für Besatzungsfragen doch nicht nur ein interessanter sozialer Mikrokosmos und ein wichtiger Impulsgeber des völkerrechtlichen Denkens der Besatzungsjahre, sondern in mehrerlei Hinsicht ein paradigmatischer und einflussreicher Akteur westdeutscher Nachkriegsgeschichte. Diese Einschätzung soll im Folgenden mithilfe von vier Thesen untermauert werden, die sich gleichzeitig als Perspektiven für eine ausführlichere Erforschung des Instituts, seiner Protagonist:innen und seiner Aktivitäten verstehen.

Die Geschichte des Instituts verweist, erstens, auf das intime Verhältnis von Wissenschaft (namentlich Rechtswissenschaft) und Politik. Unter dem Deckmantel einer angeblich neutralen, objektiven und von wissenschaftlichen Interessen geleiteten Dokumentation alliierter Besatzung in Deutschland betätigten sich seine Mitarbeiter:innen faktisch als Zulieferer einer nationalistisch grundierten Realpolitik. Trotz einer vorgeblich kooperativen Rhetorik gegenüber den westlichen Besatzungsmächten, zielte diese Politik auf eine möglichst rasche Rückgewinnung voller nationalstaatlicher Souveränität und eine künftige „Säuberung“ deutschen Rechts von alliierter Einflussnahme. Ebenso wie die politische Stoßrichtung des Instituts wurden auch die moralischen Hypotheken der NS-Zeit durch Verweise auf die Objektivität und Neutralität des Rechts kaschiert.

Vor diesem Hintergrund fungierte das Institut, zweitens, gleichermaßen als juristische Resozialisierungsinstanz und als Vorstufe bundesdeutscher Zentralverwaltung. So ermöglichte das Ethos des unpolitischen und objektiven Rechts dem Institut, sowohl NS-belastete Akteure wie Schmoller, Tobler oder den vormaligen Kommandeur der Sicherheitspolizei in Bordeaux und verurteilten Kriegsverbrecher Hans Luther[24] als auch eine „innere Emigrantin“ wie die 1936 aus dem Richteramt entfernte Hedwig Maier in seine Reihen aufzunehmen und scheinbar gegensätzliche Positionen wie die von Carlo Schmid und Carl Schmitt zusammenzudenken. Gleichzeitig war das Institut für Besatzungsfragen – ähnlich wie das MPIL, das Deutsche Büro für Friedensfragen in Stuttgart[25] oder der Heidelberger Juristenkreis[26] – ein Knotenpunkt jenes westdeutschen Netzwerks von Rechts- und Verwaltungsspezialisten, das gleichermaßen als Nukleus und Exerzierfeld künftiger Zentralverwaltung diente und erheblichen Einfluss auf die Entwicklung bundesdeutscher Eigenstaatlichkeit nehmen sollte. Auf diese Weise wurde eine Vielzahl an Einstellungen, Normen und Praktiken aus der Zeit vor 1945 in die bundesdeutsche Demokratie übernommen, die teils in die NS-Zeit, teils aber auch bis in die Weimarer Republik und das Kaiserreich zurückreichten. Die Besatzungszeit war in dieser Hinsicht alles andere als eine abseitige Episode, sondern eine entscheidende Phase deutscher Staatlichkeit.

Das Institut für Besatzungsfragen leistete, drittens, einen wichtigen Beitrag zur Formierung eines negativen historischen Narrativs über die alliierte Besatzung in Deutschland. Insbesondere das Bild von der angeblich von Ausbeutung, Bestrafung und Hunger geprägten „düsteren Franzosenzeit“[27] in Südwestdeutschland wurde wesentlich durch die Publikationen des Instituts mitbestimmt. Konstruktive Ansätze alliierter Besatzungspolitik wurden hingegen bewusst ausgeblendet. Gleichzeitig trat das Institut durch seine Publikationsreihe zur deutschen Besatzung in Europa als geschichtsrevisionistischer Akteur in Erscheinung. Denn hier bot sich ehemaligen Protagonisten der deutschen Besatzungsverwaltungen die Möglichkeit, ihr Handeln als rechtskonform darzustellen, den Mythos einer in weiten Teilen „korrekten“ Okkupation zu beschwören und vermeintlich positiven Aspekte deutscher Besatzung im Zweiten Weltkrieg neben die angeblich negativen Seiten alliierter Besatzung in Deutschland zu stellen.[28] Bis heute zitieren viele die tendenziösen Publikationen des Instituts zum Zweiten Weltkrieg als vermeintlich sachliche und verlässliche Quellen zur deutschen Besatzungspolitik. Schmoller, der wegen seiner NS-Vergangenheit 1968 als deutscher Botschafter in Stockholm zurücktreten musste,[29] veröffentlichte sogar noch 1979 in den angesehenen Vierteljahrsheften für Zeitgeschichte einen vorgeblich neutralen und objektiven Aufsatz über die deutsche Besatzung in Böhmen und Mähren.[30]

Das Institut ist insofern, viertens, ein Paradebeispiel für die inneren Widersprüche bundesdeutscher Demokratisierungsprozesse. Seine Erforschung kann einen Beitrag leisten zur Beantwortung der Frage, wie Mitmacher:innen und Mitläufer:innen der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft zu Protagonist:innen und Gestalter:innen einer im Großen und Ganzen funktionierenden Demokratie werden konnten. Am Beispiel des Instituts lassen sich dabei drei Pfade der Demokratisierung aufzeigen: die aktive Mitwirkung an demokratisch legitimierten Institutionen und Prozessen,[31] die Neuperspektivierung und narrative Umdeutung des eigenen Verhaltens im Nationalsozialismus[32] sowie die Abgrenzung gegenüber dem als totalitär charakterisierten, zunehmend mit dem Nationalsozialismus gleichgesetzten Kommunismus in Ostdeutschland und Osteuropa.[33] Alle drei Pfade machen deutlich, dass das Bekenntnis zur Demokratie auch und gerade unter Jurist:innen keine Herzensentscheidung war. Ob beziehungsweise in welchem Maße die Abwendung von autoritären Denkmustern und die Hinwendung zur Demokratie von den beteiligten Akteur:innen tatsächlich internalisiert wurden, wäre für jeden Einzelfall zu prüfen. So unbefriedigend und beunruhigend uns diese Feststellung erscheinen mag: Viele dürften schlichtweg von Mitläufer:innen des Nationalsozialismus zu Mitläufer:innen der Demokratie geworden sein.

***

[1] Foto: Gustav von Schmoller, Erneuter Souveränität entgegen. Wie es zur Gründung eines Instituts für Besatzungsfragen in Tübingen kam, in: Tübinger Blätter 64 (1977), 65–71, 65.

[2] Zur Biografie Carlo Schmids siehe, nach wie vor grundlegend: Petra Weber, Carlo Schmid, 1896–1979. Eine Biographie, München: Beck 1996.

[3] Gustav von Schmoller, Das Institut für Besatzungsfragen in Tübingen, in: Max Gögler/Gregor Richter (Hrsg.), Das Land Württemberg-Hohenzollern 1945–1952. Darstellungen und Erinnerungen, Sigmaringen: Thorbecke 1982, 447–470, 447.

[4] Carl Schmitt, Tagebücher 1930–1934, hg. von Wolfgang Schuller in Zusammenarbeit mit Gerd Giesler, Berlin: Akademie Verlag 2010, Eintrag vom 23.7.1934, 351.

[5] Dirk Blasius, Carl Schmitt und Botschafter Gustav von Schmoller. Zur juristischen Erblast im Auswärtigen Amt, Kritische Justiz 46 (2013), 67–79, 69–70.

[6] Gustav von Schmoller, Die Neutralität im gegenwärtigen Strukturwandel des Völkerrechts, Univ.-Diss., Berlin: Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität 1944.

[7] Carlo Schmid, Erinnerungen, Bern: Scherz 1979, 337.

[8] Schmoller, Das Institut (Fn. 3), 450–452.

[9] Vgl. Wolfgang Bocks, Dr. Achim Tobler. Manager in der Kriegswirtschaft, in: Wolfgang Proske (Hrsg.), Täter, Helfer, Trittbrettfahrer, Bd. 6: NS-Belastete aus Südbaden, Gerstetten: Kugelberg 2017, 343–354.

[10] Vgl. Marion Röwekamp, Juristinnen. Lexikon zu Leben und Werk, Baden-Baden: Nomos 2005, 232–235.

[11] Schmoller, Das Institut (Fn. 3), 448–449; Schmoller, Souveränität (Fn. 1), 69.

[12] Foto: MPIL.

[13] Hierzu sind sämtliche Gutachten der Berliner Abteilung im Bibliotheksmagazin des MPIL überliefert. Aber auch das Heidelberger Institut befasste sich mit den Folgen der Besatzung: Vgl. Hermann Mosler/Karl Doehring (Hrsg.), Die Beendigung des Kriegszustands mit Deutschland nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg. Bearbeitet mit einer Studiengruppe des Max-Planck-Instituts für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, Köln: Carl Heymanns Verlag 1963. Auch die Heidelberger Gutachten sind im Bibliotheksmagazin überliefert.

[14] Siehe hier: Korrespondenz zwischen dem MPIL und dem Institut für Besatzungsfragen, Ordner „Übernahme des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen durch das Max-Planck-Institut für Völkerrecht“, Bestand MPIL.

[15] Felix Lange, Praxisorientierung und Gemeinschaftskonzeption. Hermann Mosler als Wegbereiter der westdeutschen Völkerrechtswissenschaft nach 1945, Berlin: Springer 2017, 131–132.

[16] BArch Koblenz, B 120 Institut für Besatzungsfragen (1947–1960).

[17] Staatsarchiv Sigmaringen, Wü 6 T 1 Institut für Besatzungsfragen (1946–1960).

[18] Siehe etwa Institut für Besatzungsfragen, Besatzungskosten – ein Verteidigungsbeitrag?, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1950; Institut für Besatzungsfragen, Das DP-Problem. Eine Studie über die ausländischen Flüchtlinge in Deutschland, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1950; Institut für Besatzungsfragen, Sechs Jahre Besatzungskosten. Eine Untersuchung des Problems der Besatzungskosten in den drei Westzonen und in Westberlin 1945–1950, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1951.

[19] Studien des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen in Tübingen zu den deutschen Besetzungen im 2. Weltkrieg, 20 Bde., Tübingen: Institut für Besatzungsfragen, 1953–1961.

[20] Siehe etwa Gustav von Schmoller/Hedwig Maier/Achim Tobler, Handbuch des Besatzungsrechts, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1957.

[21] Schmoller, Das Institut (Fn. 3); Schmoller, Souveränität (Fn. 1).

[22] Blasius, Carl Schmitt (Fn. 5).

[23] Foto: Wikimedia.

[24] So konnte Luther, der während des Krieges als Kommandeur der Sicherheitspolizei und des Sicherheitsdienstes in Bordeaux tätig war und dafür 1953 in Frankreich verurteilt wurde, in der Schriftenreihe des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen seine eigene, apologetische Sicht auf die deutsche Besatzungspolitik und die Bekämpfung der Résistance darlegen: Vgl. Hans Luther, Der französische Widerstand gegen die deutsche Besatzungsmacht und seine Bekämpfung, Tübingen: Institut für Besatzungsfragen 1957; Siehe auch Gerhard Bökel, Bordeaux und die Aquitaine im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Nazi-Besatzung und Kollaboration, Widerstand der Résistance und bundesdeutsche Nachkriegskarrieren, Frankfurt a.M.: Brandes & Apsel 2022, insbes. 211–232.

[25] Siehe Heribert Piontkowitz, Anfänge westdeutscher Außenpolitik 1946–1949. Das Deutsche Büro für Friedensfragen, Stuttgart: DVA 1978.

[26] Siehe Philipp Glahé, Amnestielobbyismus für NS-Verbrecher. Der Heidelberger Juristenkreis und die alliierte Justiz 1949–1955, Göttingen: Wallstein 2024.

[27] Siehe Edgar Wolfrum, Das Bild der „düsteren Franzosenzeit“. Alltagsnot, Meinungsklima und Demokratisierungspolitik in der französischen Besatzungszone nach 1945, in: Stefan Martens (Hrsg.), Vom „Erb- feind“ zum „Erneuerer“. Aspekte und Motive der französischen Deutschlandpolitik nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, Sigmaringen: Thorbecke 1993, 87–113; Corine Defrance/Ulrich Pfeil, Deutsch-Französische Geschichte, Bd. 10: Eine Nachkriegsgeschichte in Europa 1945 bis 1963, Darmstadt: WBG 2011, 145–159.

[28] Vgl. etwa: Luther, Widerstand (Fn. 24); Otto Bräutigam, Überblick über die besetzten Ostgebiete während des 2. Weltkrieges, Tübingen: Institut für Besatzungsfragen 1954; Robert Herzog, Besatzungsverwaltung in den besetzten Ostgebieten – Abteilung Jugend – Insbesondere: Heuaktion und SS-Helfer-Aktion, Tübingen: Institut für Besatzungsfragen 1960.

[29] Blasius, Carl Schmitt (Fn. 5), 70–71.

[30] Gustav von Schmoller, Heydrich im Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 27 (1979), 626–645.

[31] Siehe dazu die sogenannte „Behördenforschung“ der letzten zwei Jahrzehnte, die einerseits das hohe Maß an NS-Belastung in den bundesdeutschen Behörden und Ministerien nach 1945, andererseits aber auch die erstaunlich reibungslose Eingliederung vormaliger Nationalsozialist:innen und Mitläufer:innen in die neue, demokratische Ordnung herausgearbeitet hat: Vgl. etwa Eckart Conze/Annette Weinke, Krisenhaftes Lernen? Formen der Demokratisierung in deutschen Behörden und Ministerien, in: Tim Schanetzky et al. (Hrsg.), Demokratisierung der Deutschen. Errungenschaften und Anfechtungen eines Projekts, Göttingen: Wallstein 2021, 87–101.

[32] Siehe dazu etwa: Hanne Leßau, Entnazifizierungsgeschichten. Die Auseinandersetzung mit der eigenen NS-Vergangenheit in der frühen Nachkriegszeit, Göttingen: Wallstein 2020; Mikkel Dack, Everyday Denazification in Postwar Germany. The Fragebogen Questionnaire and Political Screening during the Allied Occupation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2023.

[33] Siehe dazu etwa Stefan Creuzberger/Dierk Hoffmann (Hrsg.), „Geistige Gefahr“ und „Immunisierung der Gesellschaft“. Antikommunismus und politische Kultur in der frühen Bundesrepublik, München: Oldenbourg 2014.

English

What was the Institute for Occupation Studies?

The former headquarters of the Institute for Occupation Studies at Stauffenbergstraße 32 in Tübingen[1]

In October 1947, a ‘Department for Constitutional and Occupation Issues’ was set up in the Württemberg-Hohenzollern State Chancellery at the instigation of the then Minister of Justice and Deputy State President, Carlo Schmid.[2] At the beginning of 1949, the Institute for Occupation Studies (Institut für Besatzungsfragen) emerged from this department and moved into a villa at Stauffenbergstraße 32 on the Österberg in Tübingen in 1950. Formally, the Institute was a politically independent organisation with academic aspirations. In fact, however, it fulfilled an advisory and collaborative function for the Württemberg state government. Its focus soon expanded to include all three western occupation zones. Its declared intention was to document the impact of the occupying powers on Germany, to create a systematic overview of the norms of occupation law and to quantify the financial burden and damage caused by allied occupation.[3] In addition to publications on occupation law and practice, the Institute prepared legal opinions for political institutions and private or private-sector actors. The Institute for Occupation Studies and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (KWI) and the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (MPIL) had numerous connections in terms of the subject matter of their work and in terms of personnel. For this reason, a large collection of documents from the Institute for Occupation Studies has been stored in the MPIL’s library since its termination in 1960.

Gustav von Schmoller (1907–1991) became head of the Institute for Occupation Studies. Schmoller came from a family of Prussian army officers and was the grandson of the national economist and historian of the same name. From 1925 to 1929, he had studied law, partly in Tübingen under Carlo Schmid, who had been a lecturer at the KWI in Berlin in 1928 and had dealt with reparations and restitution issues arising from the Treaty of Versailles. Schmoller had joined the NSDAP in May 1933. From May 1934, he worked for several months in Berlin as an assistant to Carl Schmitt, who had become as a scientific member of the KWI in 1933. Schmoller was apparently closely involved in the writing of the essay Der Führer schützt das Recht (“The Führer Upholds the Law”),[4] in which Schmitt gave legal absolution to Hitler’s actions in the course of the so-called Röhm Purge (also known as “The Night of the Long Knives”). In 1935, Schmoller became an officer in the Reich Ministry of Economics. After a stopover in the private sector, he held various positions in the German protectorate administration for Bohemia and Moravia from November 1939 onwards.[5] In 1941 he defended his dissertation, supervised by Schmitt, on the so-called Großraum-order and neutrality.[6] The second examiner of the thesis was Viktor Bruns, then head of the KWI for Comparative Public Law and International Law.

Just shortly after the end of the war, Schmoller became one of the closest advisors to Carlo Schmid, who, as a confidant of the French occupying power and member of the re-established Social Democratic Party of Germany (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD), was one of the leading players in the reconstruction of political life in Tübingen and Württemberg-Hohenzollern. Among other things, Schmoller accompanied Schmid to the constitutional convention on Herrenchiemsee island in August 1948. According to Schmid’s memoirs, Schmoller ‘played an outstanding role in the drafting of the memorandum […] in which the convention’s working methods and conclusions were recorded.’[7] Drawing on the resources of the Institute for Occupation Studies, Schmoller also played an important role in the negotiation, interpretation and revision of the Occupation Statute, which governed relations between the Federal Republic and the three Western occupying powers.[8] Schmoller joined the Foreign Service in autumn 1952. After working at the Bonn headquarters, as a counsellor in Athens and as consul general in Istanbul, he became the Federal Republic’s ambassador in Stockholm in 1965.

Hedwig Maier, a lawyer, and Achim Tobler, an economist, now took over the management of the Institute for Occupation Studies. Like Schmoller, the German-Swiss Tobler also had a ‘brown’ past. He had joined the SS (Schutszstaffel, literally: ‘Protection Squadron’) in 1933 and had even worked for the so called ‘Security Service of the Reichsführer-SS’ (Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführer SS) since 1939. In 1935, he had completed his doctorate under Arnold Bergstraesser in Heidelberg.[9] Hedwig Maier (née Reimer), on the other hand, was biographically out of the ordinary: In the early 1930s, she was one of the first women ever to gain a doctorate in law at the University of Berlin and found a position civil service. It was not until the mid-1930s that she had to give up her job due to the anti-women policies of the National Socialists. In 1937, she married the lawyer Georg Maier, who had repeatedly come into conflict with the Nazi regime, was drafted into the Wehrmacht in 1939 and died as a Soviet prisoner of war in October 1945. After the war, Maier settled in Tübingen with her four children. She resumed her legal work at the Institute for Occupation Studies. She soon became a judge and eventually even director of the Tübingen district court.[10]

At its peak, the Institute for Occupation Studies employed sixteen permanent staff members and ten assistants. In co-operation with the University of Tübingen, several doctoral theses were produced, which were then published by the Institute. The fact that the Institute’s work was considered politically significant and useful is reflected in its funding. The state of Württemberg-Hohenzollern provided 20,000 Deutsche Mark annually. In 1949, the state of Württemberg-Baden was added as a further sponsor. From 1950, all other states also contributed an annual sum of 10,000 Deutsche Mark. In 1951, the federal government took over the basic funding. From 1954 until its dissolution in 1960, the Institute was apparently financed entirely by donations, the sale of publications, and fees for expert opinions and lectures.[11]

Sources and Current State of Research

Files of the Institute for Occupation Studies in the MPIL library archive[12]

After its termination, the Institute handed over its documents, including its library and its extensive subject index, to the MPIL, with which it had already communicated and cooperated intensively beforehand. The two institutions had a great deal of overlap in terms of their work. The MPIL also dealt intensively with occupation law issues in its research and expert opinions, often drawing parallels with the situation in Germany after the First World War and the role of the Berlin KWI in the enforcement of German legal positions then. In particular, the Institute’s department in Berlin, which existed until 1960, dealt with ‘research on the consequences of the war’ (Kriegsfolgenforschung), which included in particular issues relating to the legal status of Berlin and to the Soviet occupation zone, as well as questions of citizenship, occupation costs, damages resulting from the war and occupation and the Oder-Neisse line.[13] When the occupation statute was abolished with the Bonn-Paris Conventions of 1952 and the dissolution of the Institute for Occupation Studies was on the cards, the MPIL and its directors, Carl Bilfinger and subsequently Hermann Mosler, showed great interest in its files.[14] Hermann Mosler had already set up an advisory centre for international law and the law of occupation at the University of Bonn in 1945, together with Richard Thoma and Ernst Friesenhahn, and subsequently made a name for himself as a vehement opponent of the Allied policy of German deindustrialization, for example as an expert witness in the Nuremberg Krupp Trial in 1947/48.[15]

The MPIL handed over a large part of the material provided by the Institute for Occupation Studies to the Federal Archive in Koblenz[16] and the Sigmaringen State Archive[17] in 1970. However, some of the legal opinions are still stored in the MPIL Archive in Heidelberg. Additional archival sources can be found in the collections of former cooperation partners and in the estates of former employees. The Institute has left behind a large number of publications on Allied occupation policy in Germany[18] as well as a twenty-volume series on German occupation policy in Europe during the Second World War.[19] The results of the Institute’s work have also been incorporated into articles and monographs by its staff members.[20]

In view of the multitude of sources available, it is surprising that the work of the Institute, which is closely intertwined with the occupation period and the founding history of the Federal Republic of Germany, has received virtually no attention in historical research to date. Two essays by Schmoller provide an overview of the Institute’s history, but, as eyewitness accounts, they do not adopt a neutral perspective.[21] Dirk Blasius takes a critical look at Schmoller’s biography and his relationship with Carl Schmitt.[22] However, he only mentions the Institute for Occupation Studies in passing. Our knowledge of the Institute’s staff and activities, the content of its publications and expert opinions, its political influence, and its social resonance is extremely limited – a good 75 years after its foundation and 65 years after its dissolution. To this day, nothing is known about how it was perceived by the occupying powers.

Theses on the Historical Relevance of the Institute

Map of the occupation zones of Germany in 1945[23]

This unsatisfactory state of research is surprising, as the Institute for Occupation Studies was not only an interesting social microcosm and key actor of international law scholarship during the occupation years, but also a paradigmatic and influential player in West German post-war history more broadly. This assessment will be substantiated in the following with the help of four theses, which at the same time serve as perspectives for a more detailed study of the Institute, its protagonists and its activities.

Firstly, the history of the Institute points to the intimate relationship between research (namely jurisprudence) and politics. Under the guise of a supposedly neutral, objective documentation of the Allied occupation in Germany, guided by scientific interests, its staff effectively acted as suppliers of a realpolitik grounded in nationalist dogma. Despite an ostensibly co-operative rhetoric towards the Western occupying powers, this policy aimed to regain full national sovereignty as quickly as possible and to ‘cleanse’ German law of Allied influence in the future. Just like the political aims of the Institute, the questionable takeovers from the Nazi era were concealed by references to the objectivity and neutrality of the law.

Secondly, the Institute thus acted as both an institution of legal resocialisation and as a precursor to the central administration of the Federal Republic of Germany. The ethos of apolitical and objective jurisprudence enabled the Institute to accept into its ranks Nazi-incriminated actors such as Schmoller, Tobler or the former commander of the security police in Bordeaux and convicted war criminal Hans Luther[24] as well as an ‘inner emigrant’ like Hedwig Maier, who was removed from the judiciary in 1936, and to bring together seemingly contradictory positions such as those of Carlo Schmid and Carl Schmitt. At the same time, the Institute for Occupation Studies – similar to the MPIL, the Deutsches Büro für Friedensfragen (‘German Office for Peace Issues’) in Stuttgart[25] or the Heidelberger Juristenkreis (‘Heidelberg Lawyers’ Circle’)[26] – was a hub of precisely that West German network of legal and administrative specialists that served both as a nucleus and a training ground for the future central administration and was to exert considerable influence on the development of West German statehood. In this way, attitudes, norms, and practices from the period before 1945 were adopted into West German democracy on a large scale, some of which dated back to the Nazi era, and others to the Weimar Republic and the German Empire. In this respect, the occupation period was anything but an inconsequential episode, but rather a decisive phase of German statehood.

Thirdly, the Institute for Occupation Studies made an important contribution to the formation of a negative historical narrative about the Allied occupation in Germany. In particular, the image of the ‘gloomy French period’[27] in south-west Germany, allegedly characterised by exploitation, punishment and hunger, was significantly influenced by the Institute’s publications. Constructive approaches to Allied occupation policy, on the other hand, were deliberately ignored. At the same time, the Institute appeared as a historical revisionist actor through its series of publications on the German occupations in Europe. This was because it offered former protagonists of the German occupation administrations the opportunity to present their actions as legally compliant, to conjure up the myth of a largely ‘proper’ occupation and to present supposedly positive aspects of German occupation in the Second World War alongside the allegedly negative aspects of Allied occupation in Germany.[28] To this day, many cite the Institute’s tendentious publications on the Second World War as supposedly factual and reliable sources on German occupation policy. Schmoller, who had to resign as German ambassador in Stockholm in 1968 because of his Nazi past,[29] even published a supposedly neutral and objective essay on the German occupation in Bohemia and Moravia in the prestigious Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte as late as 1979.[30]

Fourthly, the Institute is insofar a prime example of the internal contradictions of the German democratisation processes. Researching it can contribute to answering the question of how those who participated in the Nazi tyranny could become protagonists and shapers of a generally well-functioning democracy. Using the example of the Institute, three paths of democratisation can be identified: active participation in democratically legitimised institutions and processes,[31] the re-perspectivisation and narrative reinterpretation of one’s own behaviour under National Socialism[32], and the distinction from communism in East Germany and Eastern Europe, which was characterised as totalitarian and increasingly equated with National Socialism.[33] All three paths make it clear that in committing themselves to democracy, lawyers did not follow their hearts. Whether or to what extent the rejection of authoritarian thought patterns and the turn towards democracy were truly internalised by the actors involved would have to be examined for each individual case. As unsatisfactory and unsettling as this finding may seem to us, it is likely that many simply turned from Mitläufer (hangers-on) of National Socialism into Mitläufer of democracy.

***

Translation from the German original: Sarah Gebel

[1] Photo: Gustav von Schmoller, Erneuter Souveränität entgegen. Wie es zur Gründung eines Instituts für Besatzungsfragen in Tübingen kam, in: Tübinger Blätter 64 (1977), 65–71, 65.

[2] On Carlo Schmids biography, see, still foundational: Petra Weber, Carlo Schmid, 1896–1979. Eine Biographie, Munich: Beck 1996.

[3] Gustav von Schmoller, Das Institut für Besatzungsfragen in Tübingen, in: Max Gögler/Gregor Richter (eds.), Das Land Württemberg-Hohenzollern 1945–1952. Darstellungen und Erinnerungen, Sigmaringen: Thorbecke 1982, 447–470, 447.

[4] Carl Schmitt, Tagebücher 1930–1934, ed. by Wolfgang Schuller in cooperation with Gerd Giesler, Berlin: Akademie Verlag 2010, Entry of 23.7.1934, 351.

[5] Dirk Blasius, Carl Schmitt und Botschafter Gustav von Schmoller. Zur juristischen Erblast im Auswärtigen Amt, Kritische Justiz 46 (2013), 67–79, 69–70.

[6] Gustav von Schmoller, Die Neutralität im gegenwärtigen Strukturwandel des Völkerrechts, dissertation, Berlin: Friedrich Wilhelm University 1944.

[7] Carlo Schmid, Erinnerungen, Bern: Scherz 1979, 337.

[8] Schmoller, Das Institut (fn. 3), 450–452.

[9] See: Wolfgang Bocks, Dr. Achim Tobler. Manager in der Kriegswirtschaft, in: Wolfgang Proske (ed.), Täter, Helfer, Trittbrettfahrer, Vol. 6: NS-Belastete aus Südbaden, Gerstetten: Kugelberg 2017, 343–354.

[10] See: Marion Röwekamp, Juristinnen. Lexikon zu Leben und Werk, Baden-Baden: Nomos 2005, 232–235.

[11] Schmoller, Das Institut (fn. 3), 448–449; Schmoller, Souveränität (fn. 1), 69.

[12] Photo: MPIL.

[13] All legal opinions on this by the Berlin department can be found in the MPIL’s library. But the Heidelberg Institute also dealt with the consequences of occupation, see: Hermann Mosler/Karl Doehring (eds.), Die Beendigung des Kriegszustands mit Deutschland nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg. Edited in cooperation with a study group from the MPIL, Cologne: Carl Heymanns Verlag 1963. The Heidelberg legal opinions are also stored in the library.

[14] See: Correspondence between the MPIL and the Institute for Occupation Studies, Folder ‘Übernahme des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen durch das Max-Planck-Institut für Völkerrecht’ (‘Takeover of the Institute for Occupation Studies by the Max Planck Institute for International Law’), MPIL Archive.

[15] Felix Lange, Praxisorientierung und Gemeinschaftskonzeption. Hermann Mosler als Wegbereiter der westdeutschen Völkerrechtswissenschaft nach 1945, Berlin: Springer 2017, 131–132.

[16] Federal Archive Koblenz, B 120 Institut für Besatzungsfragen (1947–1960).

[17] State Archive Sigmaringen, Wü 6 T 1 Institut für Besatzungsfragen (1946–1960).

[18] See, for example: Institut für Besatzungsfragen, Besatzungskosten – ein Verteidigungsbeitrag?, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1950; Institut für Besatzungsfragen, Das DP-Problem. Eine Studie über die ausländischen Flüchtlinge in Deutschland, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1950; Institut für Besatzungsfragen, Sechs Jahre Besatzungskosten. Eine Untersuchung des Problems der Besatzungskosten in den drei Westzonen und in Westberlin 1945–1950, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1951.

[19] Studien des Instituts für Besatzungsfragen in Tübingen zu den deutschen Besetzungen im 2. Weltkrieg, 20 Vols., Tübingen: Institut für Besatzungsfragen, 1953–1961.

[20] See, for example: Gustav von Schmoller/Hedwig Maier/Achim Tobler, Handbuch des Besatzungsrechts, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1957.

[21] Schmoller, Das Institut (fn. 3); Schmoller, Souveränität (fn. 1).

[22] Blasius, Carl Schmitt (fn. 5).

[23] Photo: Wikimedia.

[24] For example, Luther, who had been commander of the ‘Security Police’ (Sicherheitspolizei) and ‘Security Service’ in Bordeaux during the war and was sentenced for this in France in 1953, was able present his own apologetic view of German occupation policy and the fight against the Resistance in the Institute for Occupation Studies’ publication series, see: Hans Luther, Der französische Widerstand gegen die deutsche Besatzungsmacht und seine Bekämpfung, Tübingen: Institut für Besatzungsfragen 1957; see also: Gerhard Bökel, Bordeaux und die Aquitaine im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Widerstand der Résistance und bundesdeutsche Nachkriegskarrieren, Frankfurt a.M.: Brandes & Apsel 2022, esp. 211–232.

[25] See: Heribert Piontkowitz, Anfänge westdeutscher Außenpolitik 1946–1949. Das Deutsche Büro für Friedensfragen, Stuttgart: DVA 1978.

[26] See: Philipp Glahé, Amnestielobbyismus für NS-Verbrecher. Der Heidelberger Juristenkreis und die alliierte Justiz 1949–1955, Göttingen: Wallstein 2024.

[27] See: Edgar Wolfrum, Das Bild der “düsteren Franzosenzeit”. Alltagsnot, Meinungsklima und Demokratisierungspolitik in der französischen Besatzungszone nach 1945, in: Stefan Martens (ed.), Vom “Erbfeind” zum “Erneuerer”. Aspekte und Motive der französischen Deutschlandpolitik nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, Sigmaringen: Thorbecke 1993, 87–113; Corine Defrance/Ulrich Pfeil, Deutsch-Französische Geschichte, Vol. 10: Eine Nachkriegsgeschichte in Europa 1945 bis 1963, Darmstadt: WBG 2011, 145–159.

[28] See, for example: Luther, Widerstand (fn. 24); Otto Bräutigam, Überblick über die besetzten Ostgebiete während des 2. Weltkrieges, Tübingen: Institut für Besatzungsfragen 1954; Robert Herzog, Besatzungsverwaltung in den besetzten Ostgebieten – Abteilung Jugend – Insbesondere: Heuaktion und SS-Helfer-Aktion, Tübingen: Institut für Besatzungsfragen 1960.

[29] Blasius, Carl Schmitt (fn. 5), 70–71.

[30] Gustav von Schmoller, Heydrich im Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 27 (1979), 626–645.

[31] See the so-called “research on authorities” (Behördenforschung) of the last two decades, which on the one hand has highlighted the high level of Nazi contamination in the Federal German authorities and ministries after 1945, but on the other hand also the surprisingly smooth integration of former National Socialists and hangers-on into the new, democratic order: See, for example: Eckart Conze/Annette Weinke, Krisenhaftes Lernen? Formen der Demokratisierung in deutschen Behörden und Ministerien, in: Tim Schanetzky et al. (eds.), Demokratisierung der Deutschen. Errungenschaften und Anfechtungen eines Projekts, Göttingen: Wallstein 2021, 87-101.

[32] See on this, for example: Hanne Leßau, Entnazifizierungsgeschichten. Die Auseinandersetzung mit der eigenen NS-Vergangenheit in der frühen Nachkriegszeit, Göttingen: Wallstein 2020; Mikkel Dack, Everyday Denazification in Postwar Germany. The Fragebogen Questionnaire and Political Screening during the Allied Occupation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2023.

[33] See on this, for example: Stefan Creuzberger/Dierk Hoffmann (eds.), „Geistige Gefahr“ und „Immunisierung der Gesellschaft“. Antikommunismus und politische Kultur in der frühen Bundesrepublik, Munich: Oldenbourg 2014.

Johannes Großmann ist Inhaber des Lehrstuhls für Zeitgeschichte am Historischen Seminar der LMU München.

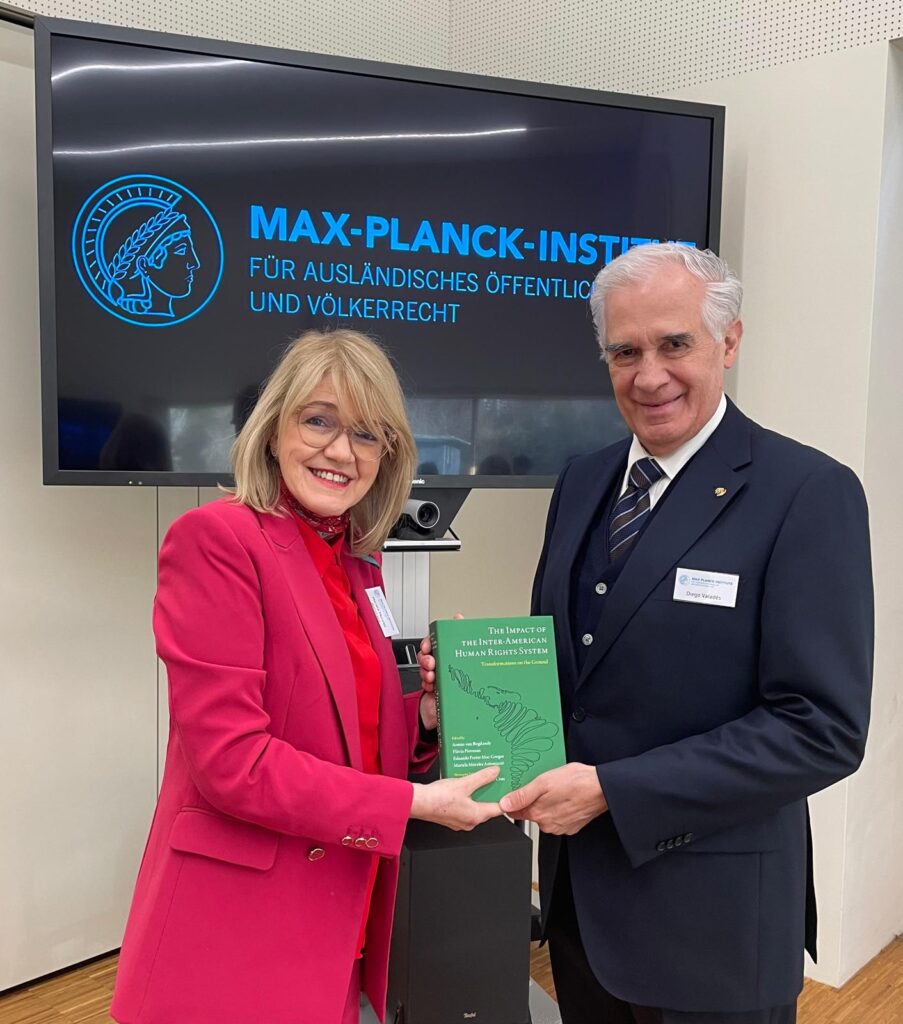

Mariela Morales Antoniazzi ist seit 2006 als wissenschaftliche Referentin am MPIL, wo sie das Projekt Ius Constitutionale Commune en América Latina (ICCAL) leitet.

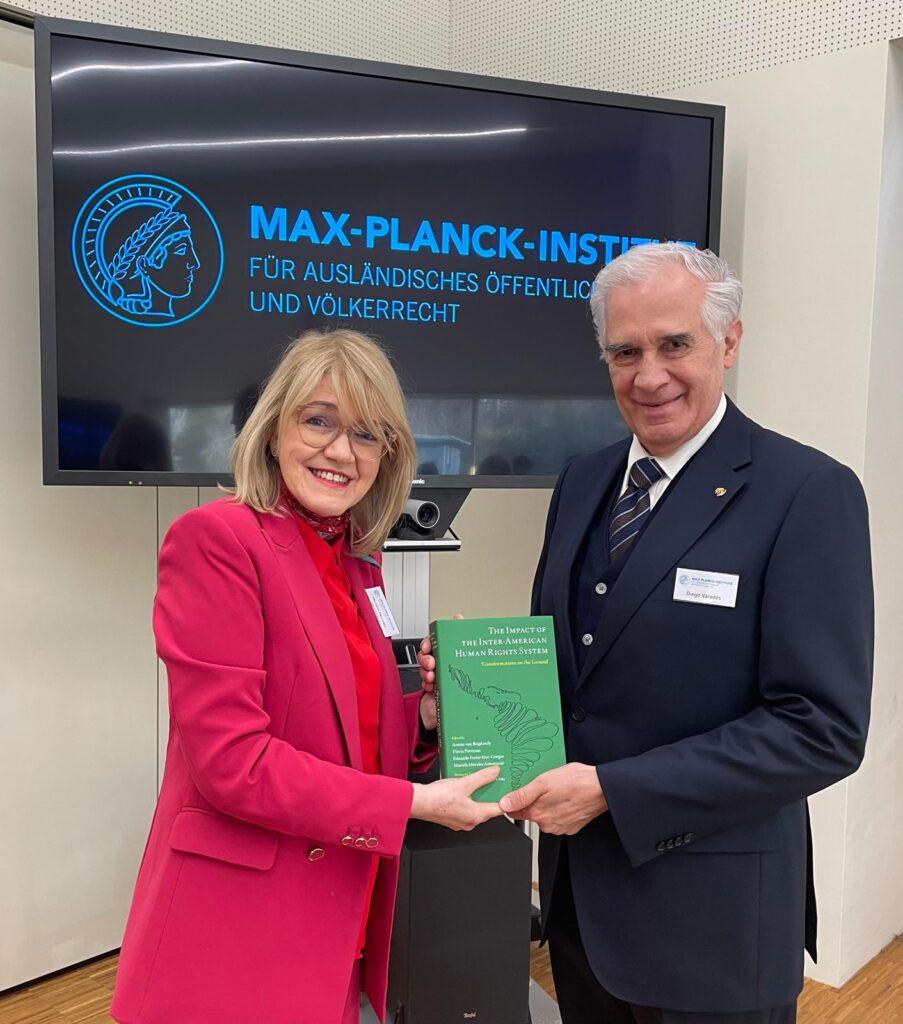

Mariela Morales Antoniazzi ist seit 2006 als wissenschaftliche Referentin am MPIL, wo sie das Projekt Ius Constitutionale Commune en América Latina (ICCAL) leitet.