Ein Jahr ist es her, dass das Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht am 19. Dezember 2024 sein hundertjähriges Bestehen gefeiert hat. Allein seit dieser Feier hat am Institut eine Vielzahl größerer und kleinerer Festlichkeiten stattgefunden: Es wurden 21 Jahre ICCAL begangen sowie zwei Geburtstage (der 60. Geburtstag von Direktorin Anne Peters, mit Kolloquium, und der 85. Geburtstag des ehemaligen Bibliotheksdirektors Joachim Schwietzke). Hinzu kamen: eine Ehrendoktorwürde von Anne Peters, zwei Dissertationsverteidigungen, eine Habilitation, mehrere wissenschaftliche Auszeichnungen für Institutsangehörige, eine Sommer- und eine Weihnachtsfeier, ein Betriebsausflug und eine Bernhardt-Lecture mit Alumni-Treffen, zuzüglich zu den monatlichen „Guest drinks“, sozialen Zusammenkünften bzw. Ausflügen der jeweiligen Forschungsgruppen und der Verabschiedung einiger Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter.

Feiern, Feste und Jubiläen strukturieren den Jahreslauf am Institut, unterbrechen Arbeit und Alltag und schließen wiederum an diese an. Gefeiert wurde in 100 Jahren Institutsgeschichte immer und Vieles – selbst in Zeiten des Krieges.[1] Kalkuliert man allein mit einer Weihnachtsfeier, einem Betriebsausflug und einem Sommerfest im Jahr, so läge man in 100 Jahren Institutsgeschichte bei mindestens 300 Feiern.[2] Grund genug, um sich mit der Geschichte der Festkultur am Institut zu befassen. Dieser Blogbeitrag möchte dies in vier Schritten tun. Einleitend gibt er einen kurzen theoretischen Überblick zur Bedeutung und Geschichte von Festen und Feiern im Allgemeinen, um dann in Teil II, III und IV die wissenschaftliche Feierkultur und die Repräsentation des Instituts nach außen bzw. die Rolle von Festen im Institut als soziale Gemeinschaft nach innen zu untersuchen.

I. „Moratorium des Alltags“ – Zur Theorie und Funktion von Festen und Feiern

Förmlich. Ansprache Hermann Mosler im Anschluss an das Kolloquium „Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit der Gegenwart“ 1962 [3]

Menschen feiern gern, und so nimmt es nicht Wunder, dass Feiern und Feste Gegenstand wissenschaftlicher Untersuchung in nahezu sämtlichen sozial- und kulturwissenschaftlichen Disziplinen von der Anthropologie und Ethnologie über die Geschichtswissenschaft, Philosophie und Theologie zur Psychologie geworden sind. Eine wichtige begriffliche und konzeptuelle Unterscheidung, die – zumindest in der deutschsprachigen – Forschung getroffen wird, ist die Differenzierung zwischen „Fest“ und „Feier“. Während die „Feier“ als ernste und erhabene (sakrale) Veranstaltung begriffen wird, die das Bekenntnis der feiernden Gemeinschaft zu den sie konstituierenden Werten in den Mittelpunkt rückt, ist das „Fest“ eine aus dem freudigen, lebensbejahenden Affekt der Teilnehmenden heraus motiviert.[4] Zeichnen sich „Feiern“ durch strenge äußere Formen wie Sinn, Ordnung und Hierarchie konstituierende Zeremonien und Rituale aus, charakterisieren sich „Feste“ durch die Infragestellung bzw. temporäre Aufhebung von sozialen Ordnungen. „Feiern“ dienen dem feiernden Kollektiv zur Selbstpositionierung in der Welt über die Einordnung in ein universales Sinnsystem und mithin zur Rückkehr zum die Gemeinschaft konstituierenden Ursprung.[5] Gefestigt und definiert wird die Gemeinschaft über Riten, die durch ihre Wiederholung und Gleichförmigkeit zentrale Glaubenssätze, Ideale und Narrative beschwören und im kollektiven Bewusstsein präsent halten.

Fetzig. Band anlässlich des Festes nach der Einführung von Karl Doehring und Jochen Frowein als Direktoren 1981[6]

Das „Fest“ indes zeichne sich laut dem französischen Psychoanalytiker Olivier Douville durch den „désordre programmé“ aus. Kernbestandteil des Festes ist der „Exzess“, den Sigmund Freud nicht nur als „gestattet“, sondern vielmehr als „geboten“ betrachtet.[7] Die soziale Ordnung, die die „Feier“ bzw. der Alltag konstituieren, wird im Fest bewusst aufgebrochen. Als bestes historisches Beispiel mag hierbei der Karneval dienen, an welchem seit dem Mittelalter sämtliche politische, religiöse und sozialen Hierarchien für einen Tag aufgehoben wurden. Dem Fest eigen ist zudem die „Subversion“ bzw. die Grenzüberschreitung.[8] Mit der Aufhebung der sozialen Ordnung geht auch die Möglichkeit der „freien Rede“ und Kritik an eben dieser Ordnung einher. Dieser „Exzess“ funktioniert jedoch lediglich auf Zeit, die Ordnung wird nicht grundsätzlich durchbrochen oder infrage gestellt. Der „gestattete“, kontrollierte Exzess hat „reinigende“ Wirkung, dient als Ventil und festigt somit wie auch die Feier die soziale Gemeinschaft.

Feste und Feiern lassen sich nicht immer trennscharf voneinander abgrenzen, oft folgt auf eine förmliche Feier ein informelles Fest. Auch gibt es soziale „Get-togethers“, die sich weder dem Fest noch der Feier eindeutig zuordnen lassen. Gemeinsam ist beiden jedoch, dass sie, in den Worten des Philosophen Odo Marquardt, ein „Moratorium des Alltags“ sind.[9] Hiermit ist zugleich ein Punkt benannt, der für die historische Betrachtung von Festen und Feiern mit Blick auf das Kaiser-Wilhelm- bzw. Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht essentiell ist: das Verhältnis von (Arbeits-) Alltag zur Fest- bzw. Feierkultur. Beides steht in einem dialogischen bzw. dialektischen Verhältnis zueinander. In Fest und Feier spiegelt sich die feiernde Gemeinschaft mit ihren Werten, Hierarchien und sozialen Zusammenhängen unauflöslich. Wer also ein Verständnis vom Institut als sozialem aber auch Wissenschaftsort entwickeln möchte, der muss die Fest- und Feierkultur in gleichem Maße in den Blick nehmen, wie die wissenschaftliche Arbeit.[10]

II. Unfähig, zu feiern? – Das Institut und seine Außendarstellung

Politische Feier-Kultur. Von einem Institutsmitarbeiter angefertigte Fotografie vom Institutssitz im Berliner Stadtschloss auf den Lustgarten anlässlich des Einzugs der Spanischen „Legion Condor“ 1938 [11]

In Anlehnung an die berühmte Studie des Psychoanalytiker-Ehepaares Alexander und Marianne Mitscherlich, die der deutschen Nachkriegsgesellschaft 1967 aufgrund ihres Unwillens zur Auseinandersetzung mit den Verbrechen der NS-Zeit eine „Unfähigkeit zu trauern“ attestiert hatten, fällt in der historischen Forschung in Bezug auf Deutschland nicht selten die Formel der „Unfähigkeit zu feiern“.[12] Diese „Unfähigkeit“ wird insbesondere auf den Umgang mit der NS-Vergangenheit bezogen, hat in jüngster Zeit aber auch Anwendung auf die Postmoderne im Allgemeinen gefunden, der die großen „feierwürdigen“ Narrative und Wertbilder abhandengekommen seien. Auch in Bezug auf das Institut zeigt sich lange Zeit eine gewisse „Unfähigkeit zu feiern“, die gleichermaßen in seiner Gründungsgeschichte wie auch in seinem Umgang mit den Weltkriegen und der NS-Zeit begründet liegt.[13]

1. Keine Feierstimmung? Das Berliner KWI 1924–1945

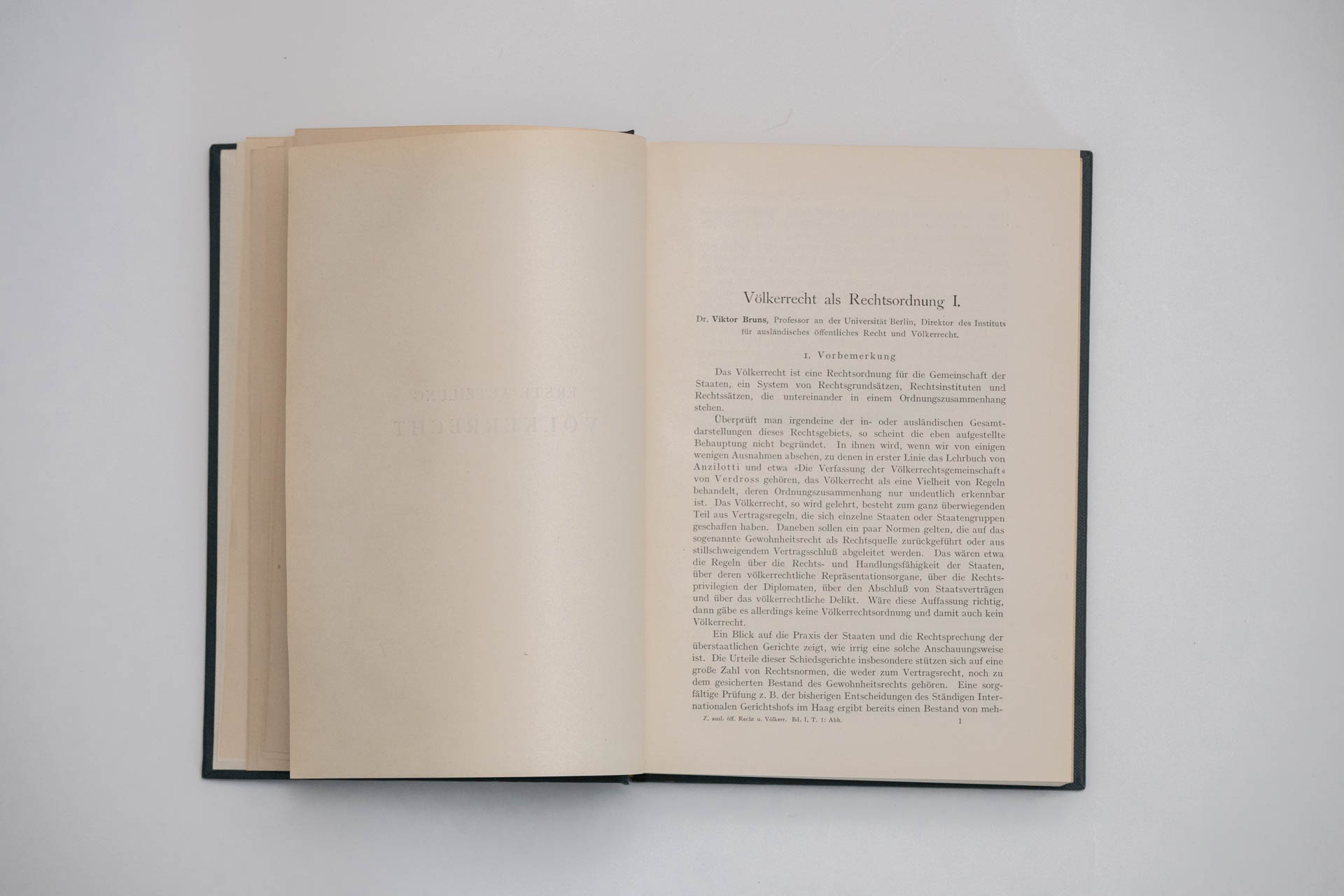

Arbeitet man sich durch die überlieferten Unterlagen zur Institutsgeschichte, so fällt ein gewisses Missverhältnis ins Auge: Wenngleich seit Gründung des KWI eine Vielzahl von Festen überliefert ist, so gibt es doch bis in die 1950er Jahre keine Feier. Bereits die Gründung des Instituts ging glanzlos und ganz ohne Festakt über die Bühne. Dies lag zum einen an den konkreten Umständen der Gründung im Dezember 1924, welche – in wirtschaftlich schwierigen Zeiten – eher zufällig geschah, da die Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft kurz vor Ablauf des Geschäftsjahres noch über Gelder verfügte, die kurzfristig für den Aufbau des Instituts investiert wurden.[14] Wenngleich das politische und wissenschaftliche Interesse an einem KWI für Völkerrecht groß war, waren der Erhalt und Ausbau des Instituts über Jahre hinweg unsicher und letztendlich vor allem Viktor Bruns‘ beharrlicher Lobbyarbeit in KWG, Ministerien und Politik zu verdanken. Die Anfänge des Instituts waren somit von Bescheidenheit und Unsicherheit gekennzeichnet. Auch darüber hinaus hatte es keine rechte „Feierstimmung“ gegeben: Das KWI war in eine politisch ernste Situation hineingegründet worden, die nicht von feierlichem Bekenntniswillen zu Frieden und Völkerverständigung getragen war, sondern von der Auseinandersetzung mit den Folgen des Versailler Vertrages für Deutschland.

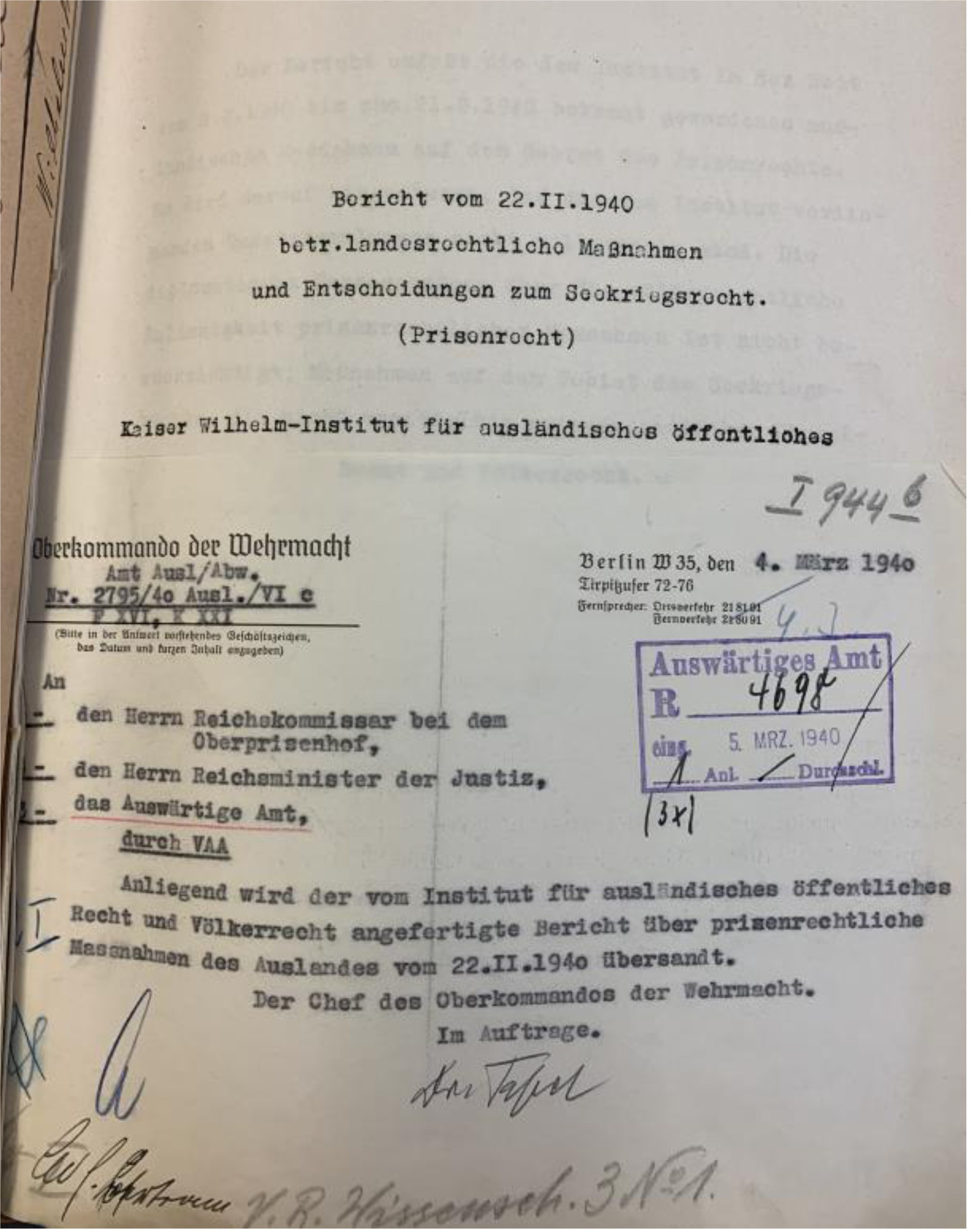

In dem Moment, in dem es für das Institut tatsächlich Anlass zur „Feier“ hätte geben können, hatten sich die politischen Vorzeichen abermals drastisch verändert. Als erste größere Festivität der Institutsgeschichte ist das zehnjährige Jubiläum 1934 überliefert. Dieses wurde jedoch nicht als „Feier“, sondern als rein institutsinternes „Fest“ begangen. Dies mag auf den Umstand zurückzuführen sein, dass man bei einem zehnjährigen Jubiläum in der Regel noch keine großen öffentlichen Feiern ausrichtet, zudem mag aber auch der politische Machtwechsel 1933 eine Rolle gespielt haben. Denn: Eine Feier im „Dritten Reich“ hätte unausweichlich ein politisches Ereignis darstellen müssen, das nicht ohne ostentatives Bekenntnis zur neuen Ideologie ausgekommen wäre. Die Haltung von Viktor Bruns und dem Institut war in dieser Frage hochkomplex. Wenngleich Bruns die Nähe der neuen Machthaber suchte und das Kunststück vollbrachte, das KWI strategisch so gut aufzustellen, dass er die „Gleichschaltung“ verhinderte, ist sein Verhältnis, wie das des Großteils der Mitarbeiterschaft, zum Nationalsozialismus zwiespältig.[15] Man stand der „nationalen Revolution“ anfänglich nicht ablehnend gegenüber und bejahte Vieles, blieb aber dennoch skeptisch. Trotz Staatsnähe und NS-konformen personalpolitischen Maßnahmen, hielt sich das KWI mit öffentlichen politischen Stellungnahmen zurück – und das schloss auch Feiern mit ein. Ab 1939 verhinderte der Kriegsausbruch ohnehin jeden Anlass zur Feier, mit der Folge, dass bis zum Richtfest des Institutsneubaus in Heidelberg 1953 im Institut im eigentlichen Sinn keine einzige Feier abgehalten worden war.

2. Die Feier als Problem. Die Neugründungsphase des Instituts 1949–1959

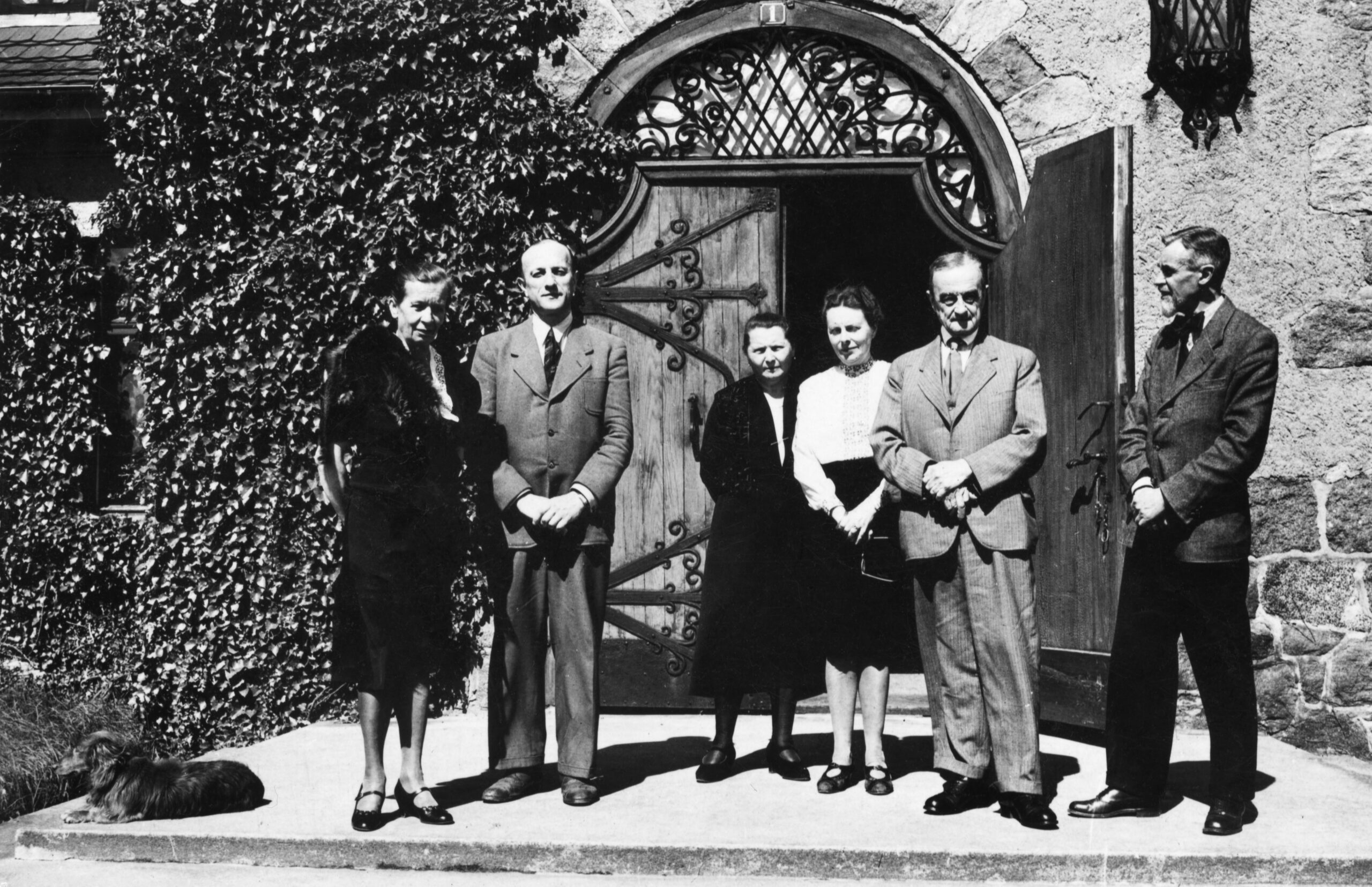

Schwierige Neukonstituierung von Wissenschaft und Institut. Carl Bilfinger (links) anlässlich der Verleihung des großen Bundesverdienstkreuzes 1953. Mit (von links nach rechts) Hermann Mosler (letzte Reihe), Günther Weiß, Kurt Schmaltz, Walter Jellinek, unbekannt, Erich Kraske und Adolf Schüle [16]

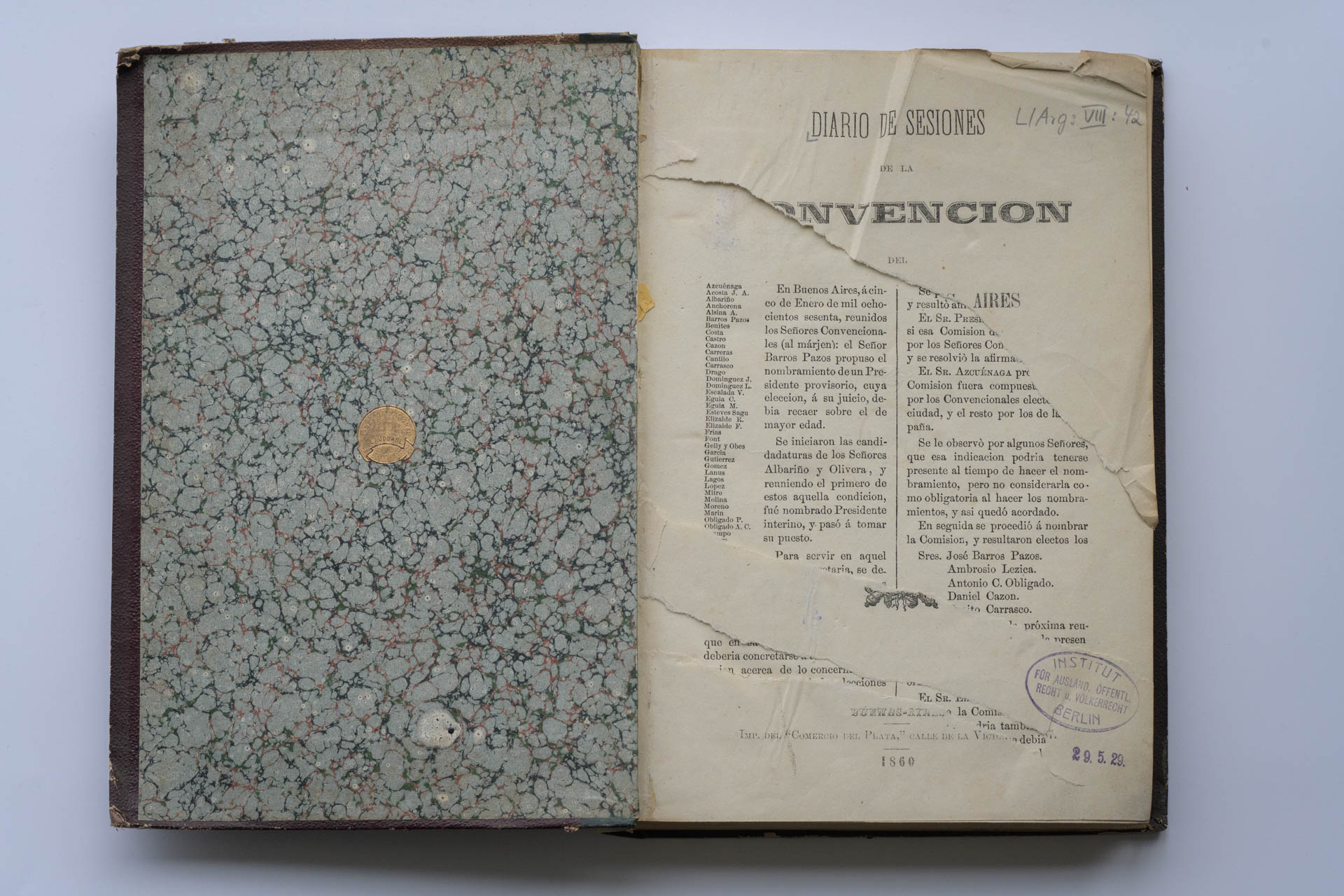

Auch der Wieder- bzw. Neuanfang des Instituts in Heidelberg ging glanzlos ohne Feier vonstatten. Zwischen 1945 und 1948 war unklar gewesen, wie und ob es mit der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft und ihren Instituten weitergehen würde. Auch das Schicksal des Völkerrechtsinstituts klärte sich erst 1949 und blieb auch nach der formellen Neugründung prekär: Teile des kriegszerstörten Instituts waren in Berlin verblieben, andere Teile notdürftig nach Heidelberg zum Wohnsitz des letzten KWI- und ersten MPIL-Direktors Carl Bilfinger transferiert worden. Der Neubeginn war aus vielen Gründen schwierig: Es mangelte an Personal, an Geld, an Büchern und an einem Institutsgebäude, zudem war der wiedereingesetzte Direktor politisch hochgradig kompromittiert und stellte eine zusätzliche Hypothek dar.[17] Auch war nach einem zweiten verlorenen Krieg unklar, welche Rolle die Völkerrechtswissenschaft und das Institut im nunmehr geteilten und international abermals isolierten Deutschland spielen konnten und sollten. Anlass zu Feierstimmung gab es jedenfalls abermals keinen.

Erst mit dem Richtfest des Heidelberger Institutsneubaus 1953 und der Einweihung des Gebäudes im Folgejahr fanden die ersten richtigen „Feiern“ des Instituts statt, doch zeichneten sich diese durch eine gewisse Richtungslosigkeit bzw. konzeptionelle Leere aus, die sich als Ausdruck der nachkriegsdeutschen „Unfähigkeit zu feiern“ lesen lässt. Zieht man die vom Richtfest überlieferte Ansprache Bilfingers und die Presseberichterstattung heran, so wird deutlich, dass es an einer grundlegenden, einer „Feier“ gemäßen Reflexion über die Selbstverortung des Instituts in seiner Zeit oder eine Formulierung eines tragbaren wissenschaftlichen Konzepts jenseits eines angesichts der historischen Ereignisse höchst fragwürdigen „Weiter-so“ mangelt.[18] Nicht nur, dass gerade Carl Bilfinger als „Mann von vorgestern“ keinerlei tragbare Zukunftsentwürfe für das Institut und die Völkerrechtswissenschaft hätte liefern können, auch jegliche Frage zur Herkunft und Tradition des Instituts hätte in der unmittelbaren Nachkriegszeit nur Fragen und Probleme aufkommen lassen, die man lieber verdrängte.[19]

Carl Bilfinger am 24. Juli 1953 bei der Grundsteinlegung des neuen Institutsgebäudes. Sein Richtspruch: „Auf den Fortbestand der Kultur, von der das Recht nur ein Teil ist.“ Am selben Tag war der mit dem Großen Bundesverdienstkreuz ausgezeichnet worden [20]

1954 standen gleich drei Groß-Ereignisse an: die offizielle Begehung des 75. Geburtstages Carl Bilfingers im Januar, die Einweihung des neuen Institutsgebäudes im Juni und die Verabschiedung Bilfingers bzw. der Amtsantritt Hermann Moslers im Oktober. Stellte sich der Bezug des neuen Gebäudes, der mit einem ausgelassenen Fest begangen wurde (dazu später mehr), als unproblematisch dar, hatte der Geburtstag Bilfingers einige Schwierigkeiten verursacht. Dieser wurde, wie auch die anlässlich des Richtfestes 1953 erfolgte Verleihung des Bundesverdienstkreuzes, in kleinem Kreis gefeiert. Zum Geburtstag erschienen sieben Institutsreferenten, sechs „Freunde des Instituts“ (vor allem KWI-Alumni), sieben Ordinarien der Heidelberger Juristischen Fakultät, der Heidelberger Oberbürgermeister und MPG-Präsident Hahn sowie einige Autoren der von Hermann Mosler und Georg Schreiber herausgegebenen Festschrift.[21] Obgleich die Einladungsliste bewusst klein gehalten war, war die Zahl an Absagen beträchtlich. Beide, Feier und Festschrift standen vor dem Problem der politischen Belastung Bilfingers, die bereits bei dessen Wiederberufung als Direktor harsche öffentliche Kritik hervorgerufen und das Ansehen des Instituts belastet hatte.[22]

Insbesondere für Hermann Mosler als früherem Mitarbeiter und Nachfolger Bilfingers als Direktor stellte die Festschrift einen schwierigen Spagat aus institutionellem Bekenntnis und politischer Abgrenzung dar. Geburtstag und Festschrift Bilfingers waren aber zugleich ein wichtiger Moment der sozialen Rekonstituierung der westdeutschen Rechtswissenschaft wie der Heidelberger Institutsgemeinschaft dar. Geht man die Namen derjenigen durch, die sich an der Festschrift beteiligt hatten bzw. die auf der „Feier“ erschienen waren, sind An- und Abwesenheiten auch als Ausdruck einer grundsätzlichen Haltung zum Institut zu lesen. So gehören beispielsweise die aufgrund ihrer jüdischen Herkunft im „Dritten Reich“ verfolgten bzw. diskriminierten Juristen Walter Jellinek, Erich Kaufmann und Karl Josef Partsch ebenso zu den Festschrift-Beiträgern wie belastete Kollegen.[23]Starke Kritik hatte Bilfingers Festschrift auch im Ausland durch den NS-Verfolgten Juristen Erich Cohn ausgelöst, der in einem Verriss in der Modern Law Review die rhetorische Frage aufwarf: „[I]s it morally right—or is it even merely politically tactful—to honour and to praise the representatives of the Nazi legal theory […]?”[24] Mosler suchte im Nachgang der Rezension den Kontakt zu Cohn und versuchte sich ihm gegenüber zu rechtfertigen. Doch Cohn blieb bei seiner Kritik und bezeichnete die Würdigung Bilfingers nicht nur als “grosses moralisches Unrecht” und “ernste Taktlosigkeit”. Insbesondere hob er die vergangenheitspolitische Dimension der Festschrift hervor:

“Man kann es verstehen, wenn die Gesinnungsgenossen solche Festtage begehen. Davon braucht man keine Notiz zu nehmen. Wenn aber andre dies tun, so ist es ein Zeichen, das nicht übersehen werden darf, – ein Zeichen dafür, wie weit das Vergessen und Vergeben gegangen ist, gerade auch bei denen, die keinen Anlass haben zu vergessen und die neben dem Vergeben auch der Vorsicht gedenken sollten.”[25]

Eine überzeugende Antwort konnte Mosler hierauf nicht geben. Fest steht nur, dass der öffentliche Umgang mit Bilfinger zu dessen Lebzeiten schwer blieb. Erst mit seinem Ableben schien für Mosler und das Institut die letzte offenkundige historische Hypothek fürs Erste gelöscht.

3. Alter Stil, doch neue Werte? Die Feier ab 1959

Bis auf den letzten Platz besetzt. Otto Hahn eröffnet den Institutsanbau mit Vortragssaal 1959 [26]

Mit dem Antritt Hermann Moslers als Direktor 1954 änderte sich viel für das Institut. Anders als Bilfinger, der vor allem ein Übergangsdirektor gewesen war, verfolgte Mosler einen klaren Westintegrations-Kurs und setzte darauf, das Institut auch international wissenschaftspolitisch zu vernetzen. Deutlich wird dies auch in der Feier-Kultur des MPIL. Waren die „Feiern“ der Jahre 1953 und 1954 noch historisch überschattet und fanden mit „angezogener Handbremse“ statt, zeigt sich bei der nächsten großen Feier anlässlich der Einweihung eines Erweiterungsbaus an das Institutsgebäude am 22. November 1959 ein ganz neuer, zukunftszugewandter und befreiter Ton.

Gefeiert wurde im neuen Vortragssaal mit 123 Gästen, mit Ansprachen von MPG-Präsident Otto Hahn und Institutsdirektor Mosler. Hermann Mosler „beschwor“ in seiner Ansprache zwar weder eine gemeinsame, die Feiergesellschaft verbindende Geschichte jenseits der „schon seit über 30 Jahren“ bestehenden „Denk- und Arbeitsweise und einer gemeinsamen Gesinnung“ („Sie finden hier den alten Stil“), noch traf er grundlegende Aussagen über die Rolle des Instituts, jenseits des Umstandes, dass „das Völkerrecht mit seiner erweiterten Entwicklung zu den internationalen, supranationalen Organisationen, also ganz neue Dinge, zu bewältigen“ habe.[27] Dennoch gehen von seiner Rede ein merklicher Optimismus und ein gemeinschafstiftender Geist aus, die aus dem Umstand resultierten, dass das Institut und seine Angehörigen nach vielen entbehrungsreichen Jahren eine angemessene Heimstätte hatten – mit einem großen Veranstaltungssaal, der Feiern und größere Fach-Veranstaltungen überhaupt erst möglich machte. Der wissenschaftliche Festvortrag, gehalten von Alumnus Hans-Joachim von Merkatz zum Thema „Das Ringen um die Verwirklichung der politischen Gemeinschaft Europas“ wies in die von Mosler verkörperte Stoßrichtung des Instituts, die in den folgenden Jahren in einer stetig steigenden Zahl internationaler Vortragsgäste sowie in den ab 1959 vom Institut und der „Heidelberger Gesellschaft“ ausgerichteten verfassungsvergleichenden internationalen Kolloquien ihre Fortsetzung fand.[28]

Vortrag Walter Hallstein 1962 im Institut [29]

Die Institutsvorträge waren in der Regel öffentlich und richteten sich nicht nur an ein wissenschaftliches Fachpublikum, sondern dienten der Vernetzung des Instituts mit Honoratioren aus Politik, Wirtschaft und Kultur. Selbstredend gab es nach jedem Vortrag auch einen Empfang.[30] Die Vortragsabende und das sich anschließende „gesellige Beisammensein“ waren für das Institut eine wichtige Gelegenheit, Verbindungen zu „Stakeholdern“ zu etablieren und zu pflegen. Die Einladungslisten waren sorgfältig zusammengestellt und es wurde darauf geachtet, dass stets regionale wie überregionale Presse berichtete.[31] Die Institutsvorträge, insbesondere jedoch die Kolloquien können als eigentlicher Beginn der „Feier-Kultur“ am Institut betrachtet werden. Zum einen sind sie sinnfälliger Ausdruck der inhaltlichen wie normativen Ausrichtung des Instituts, darüber hinaus stellten sie einen bedeutenden Sozialisationspunkt für die beteiligten Wissenschaftler und eine Möglichkeit zur Selbstrepräsentation des Instituts dar.

Heidelberger Romantik. Empfang im Haus Buhl im Anschluss an das Kolloquium „Gerichtsschutz gegen die Exekutive“ 1968 [32]

Mehr noch als die Institutsvorträge hatten die internationalen rechtsvergleichenden Kolloquien eine besondere gesellschaftliche Dimension. Neben der wissenschaftlichen Arbeit und der internationalen Vernetzung des Instituts, hatten die Abendempfänge, mit denen die Veranstaltungen beendet wurden, einen besonders festlichen Charakter. Auch hier konnte das Institut bei der internationalen Wissenschaftscommunity Eindruck machen. Die Organisation und Durchführung eines internationalen Kolloquiums mit Teilnehmern aus allen Teilen der Welt stellte im vordigitalen Zeitalter einen enormen Arbeitsaufwand dar, der große personelle und finanzielle Ressourcen band und zeitintensiv war. Auch die Reise an das Heidelberger Institut stellte für Teilnehmer aus Lateinamerika, Asien und Afrika im Wortsinne eine „Weltreise“ dar.[33] In Zeiten ohne Internet oder Zoom war ein vertiefter fachwissenschaftlicher Austausch nur persönlich möglich, was die soziale Dimension der Kolloquien noch weiter unterstreicht.

4. Kanonisierung und Vergangenheitsaversion

Feier von Hermann Moslers 85. Geburtstag 1997. Hermann Mosler und Jochen Frowein [34]

„Feiern“ gab es im Institut auch jenseits der Kolloquien viele – zu viele, um sie an dieser Stelle ausführlich zu würdigen. Erinnert sei an dieser Stelle nur die Institutsjubiläen und die runden Geburtstage von wissenschaftlichen Mitgliedern und Direktoren, die häufig zum Anlass einer Feier und einer Festschrift genommen wurden, sowie die Verabschiedungen und Einführungen von Direktoren, die ebenfalls groß begangen wurden. Stellten die Institutsjubiläen das MPIL hinsichtlich des Umgangs mit der eigenen Geschichte vor Herausforderungen, waren – mit Ausnahme Bilfingers – die Geburtstage verdienter ein dankbarerer Anlass, das Institut und seine Arbeit zu feiern.[35]

Geburtstagsfeiern waren wichtige Momente der Kanonisierung von Wissenschaftlern und ihrem Werk innerhalb von MPG und MPIL. Trotz genereller „Vergangenheitsaversion“ in der bundesrepublikanischen Gesellschaft, die wie das Institut eine Auseinandersetzung mit dem „Dritten Reich“ weitestgehend vermieden, ließen sich wissenschaftliche Biographien vergleichsweise unkompliziert würdigen: Der Fokus wurde auf die wissenschaftlichen Publikationen gelegt und als unpassend empfundene politische Verstrickungen im Lebensweg elegant umschifft. Eine besondere Rolle in der akademischen Geburtstagsfeier-Kultur von Institut, MPG und der deutschen Rechtswissenschaft spielte – quasi als Anti-Bilfinger – der im „Dritten Reich“ als Jude verfolgte und 1934 als wissenschaftliches Mitglied des KWI und Mitherausgeber der ZaöRV durch Carl Schmitt ersetzte Erich Kaufmann (1880-1972). Ausweislich der überlieferten Unterlagen im Institut gab es kein (wissenschaftliches) Mitglied, das nach 1945 häufiger und größer gefeiert worden wäre als er. 1950 war er abermals zum wissenschaftlichen Mitglied des Instituts ernannt worden, hatte unter anderem 1960 die Harnack-Medaille der MPG erhalten und war ab 1952 Mitglied des Ordens „Pour le Mérite“. Bei den Feiern im Institut wird deutlich, dass es gegenüber Kaufmann etwas gut zu machen galt. Zugleich bot sich Kaufmann zur Selbstrehabilitierung des Instituts an – an seine Verfolgung im „Dritten Reich“, die allen Institutsangehörigen entweder aus eigener Erinnerung oder als offenes Geheimnis bekannt war, wollte er tunlichst nicht erinnert werden. Somit wurden Kaufmanns Geburtstage vom Institut groß und feierlich begangen, ohne dass die NS-Zeit dabei angesprochen werden musste, was ihn für das Institut zu einem einfachen und beliebten Jubilar machte.[36] Andere NS-Verfolgte frühere Institutsangehörige wie Marguerite Wolff wurden aus dem institutionellen Kanon entweder verdrängt oder suchten, wie Gerhard Leibholz, erst nach dem Tod Bilfingers wieder die Nähe des Instituts.

Vielfach gefeiert und gewürdigt durch Festschriften und Geburtstagskolloquien und Feiern anlässlich des Amtseintritts und der Verabschiedung wurden auch Alexander N. Makarov (1888–1973)[37] und natürlich die Institutsdirektoren Hermann Mosler (1912–2001)[38], Rudolf Bernhardt (1925–2021)[39], Karl Doehring (1919–2011)[40], Helmut Steinberger (1931–2014)[41] oder Jochen Frowein (*1934)[42]. Ein gleichermaßen wichtiges Forum zur Feier des Instituts und seiner Protagonisten ist der Nachruf in der ZaöRV und, im Falle Bernhardts und Doehrings, die nach ihrem Tod eingerichteten Lectures, die im jährlichen Wechsel an zentrale Elemente im wissenschaftlichen Werk der früheren Direktoren erinnern und dieses fortentwickeln sollen.[43] Auf diese Weise wird noch eine weitere Dimension der Feier deutlich: die Aufhebung von Zeitlichkeit und die Schaffung von „Transzendenz“. Indem Kanones und über Lectures Medien der Erinnerung an Institutsakteure geschaffen werden, schreibt sich das Institut mit seinen Akteuren und Arbeiten in einen über diese hinaus weisenden Zusammenhang des „Großen und Ganzen“ ein und versucht, Geschichte, Gegenwart und Zukunft miteinander zu verbinden.

III. Der „kontrollierte Exzess“. Das Fest am Institut

Als Partylöwe bekannt: Hausmeister Theo Völker (mit Waldhorn) und Ehefrau 1981 [44]

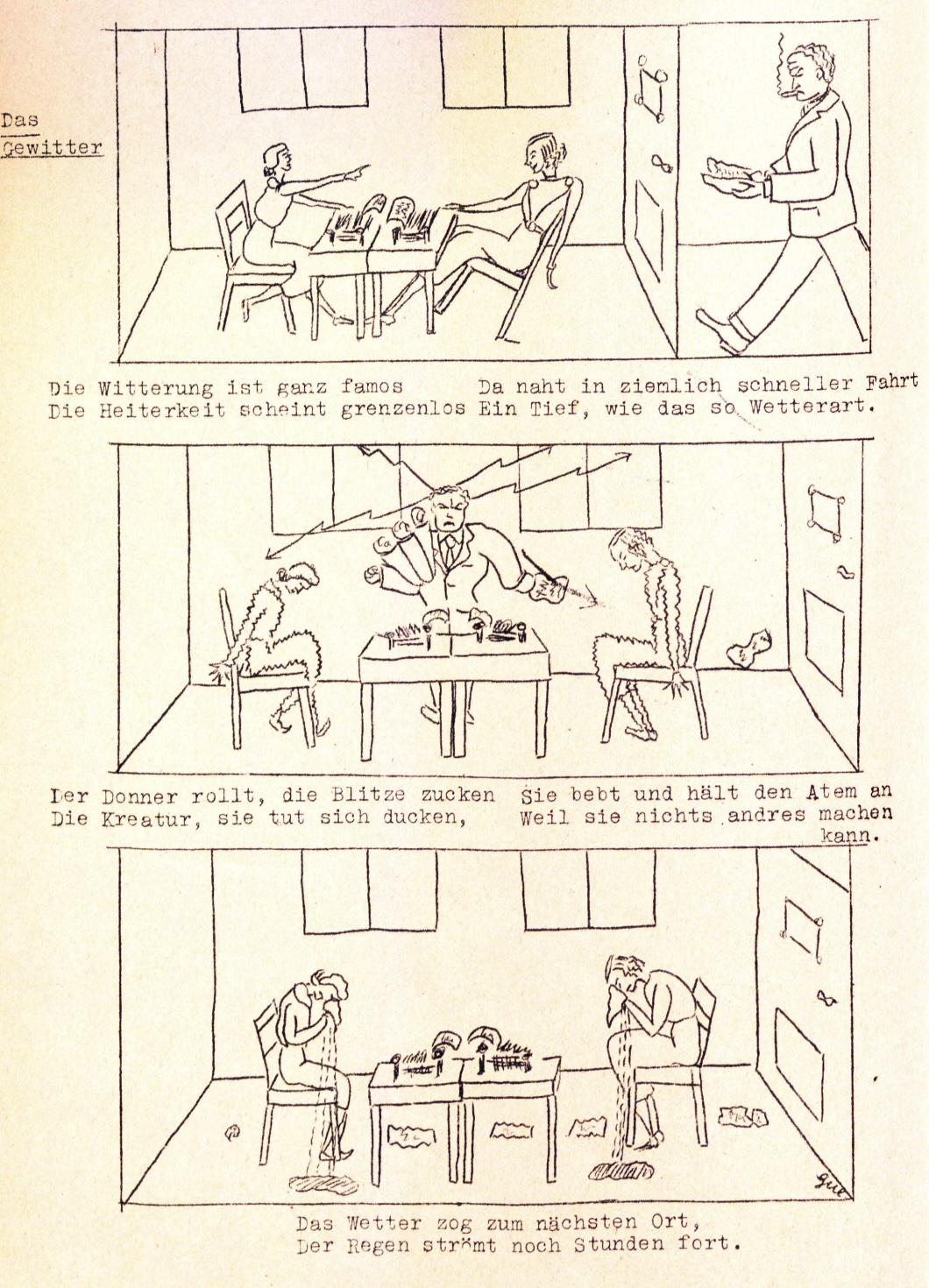

Wenngleich die Fest- und Feierforschung Deutschland eine gewisse „Unfähigkeit zu feiern“ diagnostiziert hat, war die „Fähigkeit zum Fest“ davon unberührt. Feste gab es am Institut von Anbeginn an und zu allen Lebenslagen. Zu den „Festen“ im Institut gehören viele „Sub-Genres“. An vorderster Stelle stehen natürlich Geburtstage von Institutsangehörigen, Dienstjubiläen, Weihnachtsfeiern, Sommerfeste, Betriebsausflüge, Verabschiedungen und die festliche Begehung von Promotionen bzw. Habilitationen. Oft schloss (und schließt) sich an eine förmliche „Feier“ ein informeller Teil in Form des „Festes“ an, wie zumeist bei den Festabenden anlässlich der Kolloquien. Eine besonders „doppeldeutige“ Rolle hatten die Geburtstage der Direktoren, wurden diese ab dem 60. Geburtstag einerseits mit wissenschaftlichen Festkolloquien begangen, auf denen das Werk des Jubilars von Schülern und Weggefährten gefeiert wurde. Andererseits gab es auch interne Feste mit sogenannten „Spaßfestschriften“ von Mitarbeitern. Diese Spaßfestschriften schwankten zwischen Anerkennung, Ulk, Ironie aber auch subversiver Kritik. Im Allgemeinen lässt sich über die „Feste“ am Institut festhalten, dass „Exzess“, „Grenzüberschreitung“ und „Subversion“ ebenso dazugehörten wie Teambuilding und Lebensfreude. Wie für die „Feier“ gilt auch für das „Fest“, dass es in Wechselverhältnis zum (Arbeits-) Alltag steht, den es als „Moratorium“ auflöst. Die Festkultur war und ist am Institut (vor)geprägt durch seine Größe, soziale Zusammensetzung, die historischen Umstände und die örtlichen Gegebenheiten, unter denen gearbeitet und gefeiert wurde. Zeichnete sich das Berliner KWI durch seine vergleichsweise geringe Größe und sein großbürgerlich-adliges Sozialmilieu aus (1936 hatte das Institut 20 wissenschaftliche und 21 technische Angestellte, ¼ der Mitarbeiter stammte aus ehemaligem Adel)[45], war das Heidelberger Institut sehr viel „bodenständiger“ und (bildungs-)bürgerlicher zusammengesetzt. Auch das MPIL kennzeichnete sich bis in die 2000er Jahre durch eine überschaubare und konstante Mitarbeiterzahl mit 21 wissenschaftlichen und maximal 35 nicht-wissenschaftlichen Planstellen bis in die 1990er Jahre.[46] Erst mit dem Umzug in das aktuelle Gebäude im Neuenheimer Feld begann das Institut stark zu wachsen und auch internationaler zu werden, sodass es, Stand 2024, 174 Mitarbeitende zählt, von denen 111 in der Wissenschaft tätig sind, was nicht ohne Einfluss auf die Festkultur geblieben ist.

1. Über „Fürstenlaunen“. Feste am KWI

Im Schatten des Hakenkreuzes. KWG-Betriebsfeier im Harnack-Haus, vermutlich 1939, von links am Tisch sitzend: Alexander N. Makarov, Ehepaar Schmitz, unbekannt [47]

Es lässt sich mit Sicherheit behaupten, dass es in Deutschland, vielleicht auch in Europa, in den 1920er Jahren kaum einen Ort gegeben hat, in dem man so ausgelassen und wild feiern konnte wie in Berlin. Carlo Schmid, der, aus dem beschaulichen Tübingen kommend, von 1927 bis 1928 Referent am KWI gewesen war, beschreibt seinen ersten Eindruck der Reichshauptstadt als „bestürzende“ Form der Überwältigung.[48] Wenngleich das überreiche kulturelle Angebot „ein Fest für sich“ war und Schmid bekundete „Berlin konnte kein Ort für Gelassenheit des Geistes und der Sinne sein“, war das Arbeitspensum hoch: „Fast immer blieb man bis zum späten Abend im Schloß und war dann meist zu müde, um an den Annehmlichkeiten, die die Metropole bot, teilzunehmen.“[49] Dennoch legen die überlieferten Aufzeichnungen von KWI-Angehörigen nahe, dass diese das Freizeitangebot der Stadt zu nutzen wussten und vielfach aufgrund der Möglichkeiten, die das Leben in der Reichshauptstadt bot, überhaupt erst nach Berlin gekommen waren.[50]

Institutssommerfest 1932 bei Viktor Bruns im Garten. Ehepaar Bruns (2. und 3. stehend v.l.) mit Mitarbeiterinnen [51]

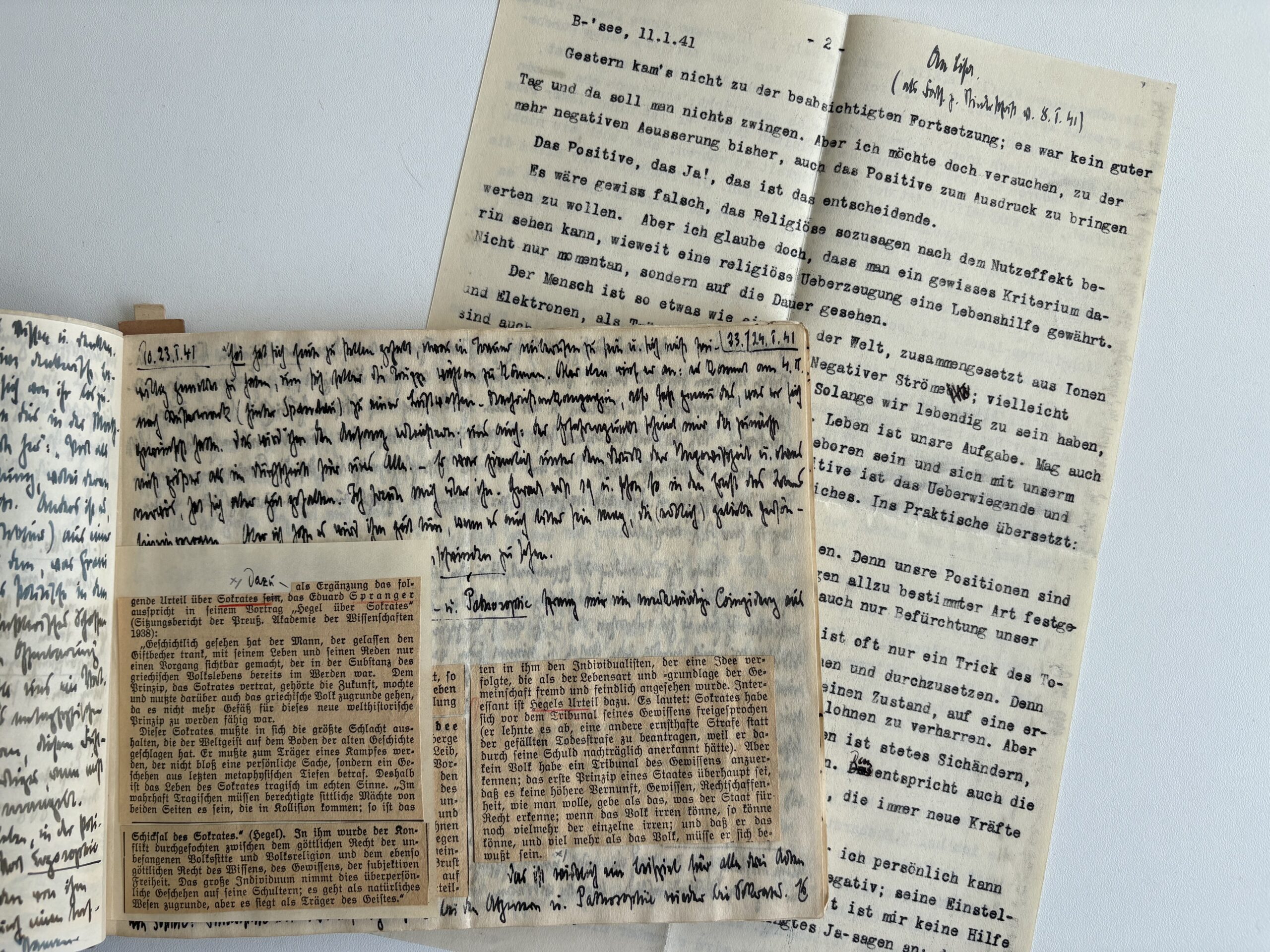

Auch wenn es am Berliner KWI im eigentlichen Sinne keine „Feiern“ gab, so gab es dennoch viele Feste, deren Form und Stil das großbürgerliche Berliner Milieu der 1920er Jahre vorzüglich zum Ausdruck bringt. Das erste große Fest in der Geschichte des Instituts fand im Dezember 1934 anlässlich seines zehnjährigen Bestehens statt. Das Jubiläum wurde jedoch nicht als (KWG-) öffentliche Feier, sondern nur im kleinen Kreis der Mitarbeiterschaft im Goethesaal des Harnack-Hauses in Berlin begangen. Was durch Tagebuchaufzeichnungen von Marie Bruns und einer von Institutsmitarbeiterinnen angefertigten Spaßfestschrift sowie dem Theaterstück „Der Jahrestag der Thronbesteigung. Eine unzeremoniöse Szene am Hofe des Fürsten Carolus des Siegreichen“ [52] als rauschendes Fest überliefert ist, zeigt bei näherer Betrachtung einige Risse. Einerseits kennzeichnet sich das Fest durch den Überschwang einer kleinen Pioniertruppe, die stolz auf zehn Jahre harter Aufbau-Arbeit und bisher Geleistetes zurückblickt. Andererseits reichen die Folgen der nationalsozialistischen „Machtergreifung“ auch tief in das soziale Gefüge des Instituts. Die als Juden verfolgten Institutsangehörigen Marguerite Wolff und Erich Kaufmann waren erst wenige Monate zuvor entlassen worden, der frühere Mitarbeiter Hermann Heller war im Exil verstorben.[53] Stattdessen hatte Viktor Bruns prononcierte Nationalsozialisten wie Carl Schmitt, Herbert Kier und Hermann Raschhofer ins Institut geholt – personalpolitische Maßnahmen, die in solch einer kleinen Forschungseinrichtung durchaus spürbar gewesen sein müssen.[54]

Hiervon ist auf dem Fest selbst jedoch nichts zu merken – im Gegenteil. Feste wollen Einheit stiften und Konflikte überkommen, Politik hat auf ihnen keinen Platz. Und so erscheint die Festgemeinschaft 1934 als vermeintlich heile Welt, die in ihrem Fest-Stil zwischen einem nahezu selbstvergessenen und gleichermaßen über den Dingen stehenden, aus Kaisers Zeiten stammenden Großbürgertum und emanzipierter Modernität schwankte, die im „Dritten Reich“ eigentlich beide keinen Platz mehr hatten. Konzipiert war das Jubiläumsfest als Überraschung für Direktor Viktor Bruns, welchem laut Aufzeichnungen seiner Frau „wochenlange Vorbereitungen“ (insbesondere der „Instituts-Damen“) vorausgegangen waren. Man begann mit einem vierhändigen Konzert auf zwei Flügeln, dargeboten von den Referenen Wilhelm Friede und Alexander N. Makarov, die „dem Wesen ihres Spiels nach Künstler“ waren, gefolgt von Flötenspiel von Joachim-Dieter Bloch. Die Sekretärinnen des Instituts boten eine Reihe von Theateraufführungen und Sketchen dar.

Ein Faible für Rokoko? 50. Geburtstag von Ehepaar Bruns. Mitarbeiterinnen führen einen Einakter im Hause Bruns auf [55]

Im Zentrum des Fests stand das Theaterstück von Direktionssekretärin Ellinor Greinert „Am Hof Karolus des Siegreichen“ in Form einer „Plauderei im Stil der Rokokozeit“:

„In geborgten Rokoko-Kostümen, deren Farbe und Art dem Charakter der Spielenden angepasst war, kamen die feinen Gestalten zu höchster Geltung. Ihre eleganten Verse sprachen sie lieblich und preziös; die Reden wurden von blumenhaften Bewegungen begleitet. Auge, Ohr, Verstand und Herz hatten ihren Hochgenuss an der Vorführung.“

Es folgte ein „kaltes Essen an langen Tafeln“, eine Ansprache des Referenten Graf Mandelsloh über den „Kameradschaftsgeist“ im Institut. Marie Bruns brachte die vermeintlich heile Festgesellschaft auf den Punkt:

„Die allgemeine Freude klang sehr hübsch in Tänzen aus, wo jung und alt, Buchbinder und Sekretärinnen, Referenten und Köchin durcheinander tanzten. Eigentlich konnte man kein Ende finden. Es war so hübsch, sich eins zu fühlen und zu spüren, wie jeder mit ganzem Herzen dabei war. Schließlich stand das Auto vor der Tür, aber meine Schlingel von Töchtern tanzten immer von uns weg und ihre Tänzer halfen ihnen aufs eifrigste bei der rhythmischen Flucht.“

Doch zeichneten sich die Feste am KWI nicht nur durch in gewisser Weise betuliche Direktorenverehrung aus, ganz im Gegenteil war der höfischen Inszenierung ein dezidiert subversiver Zug inhärent. Nicht nur in der Jubiläums-Festschrift von 1934, auch im Theaterstück über den Hof „Karolus des Siegreichen“ heißt es über den „Fürsten“: „Karolus ist nun eben l’homme de l’imprévu – So nennt Ihr das! Ich hörte davon raunen / und glaubte stets, man nennt es Fürstenlaunen.“[56] Die Sekretärinnen des Instituts zeigten zwar einerseits ihre große Anerkennung gegenüber dem Direktor, dennoch übten sie ironische Kritik an Hierarchien im Institut.[57]

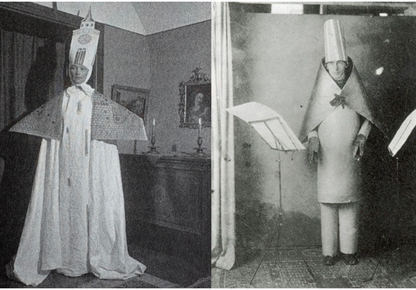

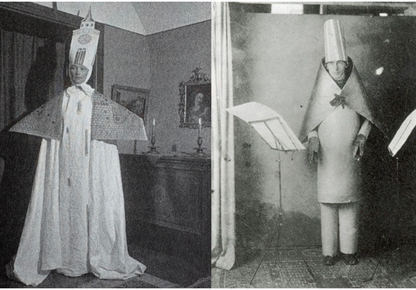

Ellinor Greinert als Tübinger Stiftskirche im Stile Hugo Balls (links), Hugo Ball im dadaistischen Kostüm (rechts) [58]

Der „avantgardistische“ Humor einiger Institutsangehöriger, wie auch das illustre soziale Umfeld des Instituts, wird unter anderem bei der Feier von Viktor und Marie Bruns‘ 50. Geburtstag im Februar 1935 deutlich, der nur wenige Wochen nach dem Jubiläum gefeiert wurde. Abermals gab es eine Rokoko-Kostüm-Aufführung, Marie Bruns gab auf dem Klavier eine „Mozartbegleitung mit recht dürftigen Trillern“ und Direktionssekretärin Ellinor Greinert trug, als Tübinger Stiftskirche verkleidet (Viktor Bruns‘ Familie stammte aus Tübingen), Gedichte vor. Das Kostüm war, in Anlehnung an Hugo Ball, von einem Freund der Familie, dem Künstler Hans Sauerbruch, einem Sohn des Chirurgen Ferdinand Sauerbruch, angefertigt worden.[59] Nicht weniger exklusiv macht die Bruns’sche Festkultur, dass die überlieferten Bilder von der seinerzeit sehr gefragten Porträtphotographin Lore Feininger, der Ex-Frau Lyonel Feiningers, angefertigt worden waren.[60]

2. „Jeder bekam ein Würstchen“. Feste am MPIL

Bescheidene Anfänge. Instituts-Weihnachtsfeier vor 1954 im Saxo-Borussen-Haus [61]

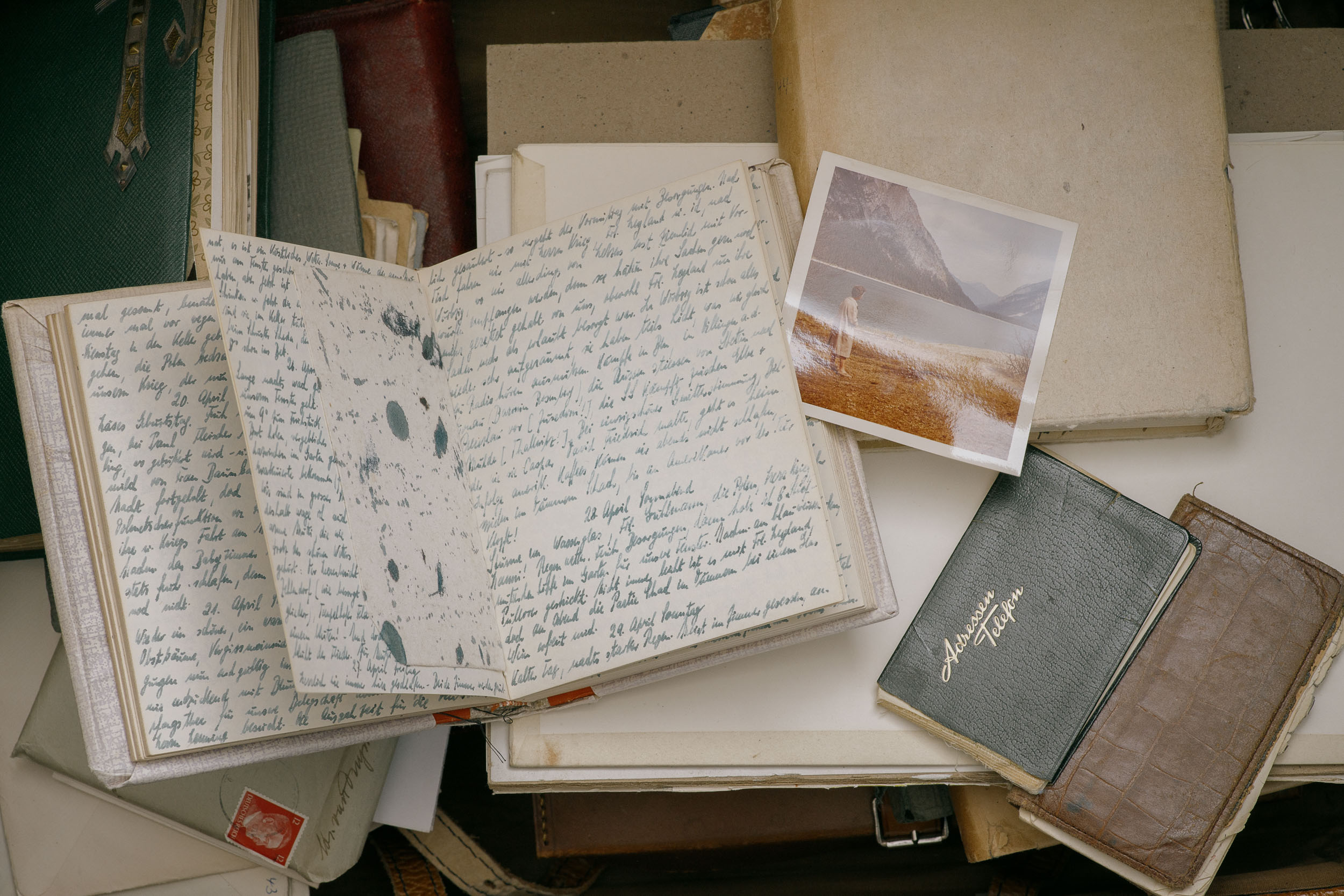

An die Berliner Festkultur konnte man am Heidelberger MPIL nicht mehr anknüpfen, zu sehr hatten sich die Zeiten und auch das Institut verändert. Mit dem Kriegsende, der Zerstörung Berlins und der alten Institutsräumlichkeiten im Berliner Stadtschloss waren die Zeiten des alten, großbürgerlich-kosmopolitischen KWI gezählt. Der Neuanfang in Heidelberg war mühsam und bescheiden. Es dauerte bis Mitte der 1950er Jahre, ehe das Institut sich wieder „gefestigt“ hatte. Erst mit Fertigstellung des Institutsgebäudes in der Berliner Straße in Heidelberg 1954 gab es wieder ein „Zentrum“, um das die Institutsgemeinschaft sich herum konstituieren konnte. Die Institutsarbeit war nicht nur zwischen Berlin, wo ein Teil der Forschungseinrichtung mit der Bibliothek verblieben war, und Heidelberg aufgeteilt, auch in Heidelberg war das Institut auf verschiedene Räumlichkeiten in der gesamten Altstadt verteilt. Wenn gefeiert wurde, so geschah dies im Esszimmer des Verbindungshauses der Saxo-Borussia, das vom Institut angemietet worden war, oder in der geräumigen Villa des Direktors Carl Bilfinger auf dem Philosophenweg. Die Feste waren dennoch von großer Einfachheit geprägt, wie Karl Doehring an die Instituts-Weihnachtsfeiern zurückerinnert: „Es gab einen Weihnachtsbaum und jeder bekam ein Würstchen.“[62] Doch ab Mitte der 1950er ließ man langsam die Bescheidenheit hinter sich, insbesondere der Wurst-Konsum sollte sich in den folgenden Jahrzehnten beträchtlich steigern. Mit dem generellen materiellen und gesellschaftlichen Aufschwung im Zeitalter des „Wirtschaftswunders“ ging es natürlich auch mit dem Institut „bergauf“, was sich auch in den Institutsfesten spiegelt.

3. Aber bitte mit Sahne. Fest und Konsum

„Den Hunger besiegt”. Rudolf Bernhardt am Buffet anlässlich der Einführung von Karl Doehring und Jochen Frowein als Mit-Direktoren 1981 [63]

Als, wie bereits angeführt, erste größere Feier am Institut kann die Einweihung des neuen Institutsgebäudes 1954 gelten. Im Anschluss an die Feier folgte ein Fest in den „Stadthallen Gaststätten“ mit 110 Gästen (mit ungefähr paritätischer Geschlechterverteilung, da seinerzeit die Teilnahme von Ehepartnerinnen und -partnern als selbstverständlich erachtet wurde). Die überlieferte Rechnung bestätigt den langsamen Wirtschaftsaufschwung in der Bundesrepublik.[64] Ausweislich des Menus speiste man Ochsenschwanzsuppe mit Roastbeef (rosa gebraten) zu „pommes frites“ (seinerzeit noch kein Fastfood) an Salat. Zum Dessert gab es „Fürst Pückler Eis mit Sahne und Waffel“. Interessanter liest sich der Getränkeverzehr, sind doch auf der Abrechnung 103 Flaschen Wein für 110 Personen aufgeführt, zuzüglich 36 Flaschen Bier und 23 Gläsern Weinbrand. An Nicht-Alkoholika wurden lediglich 28 Flaschen Wasser, 5 Gläser Traubensaft und eine Flasche Coca-Cola (seinerzeit ein noch eher „exklusives“ amerikanisches Getränk) konsumiert. Stellt man dann noch in Rechnung, dass entsprechend den Konventionen der Zeit der Großteil des Alkohols von den 55 geladenen Herren verzehrt wurde, ergibt sich ein stolzer Pro-Kopf-Verbrauch. Hinzu kamen 76 Zigarren und 16 Schachteln Zigaretten, die in der Gaststätte erworben wurden – zuzüglich zu den von den Gästen bereits mitgeführten Rauchwaren.

Nichts für schwache Mägen. Buffet anlässlich der Amtseinführung von Karl Doehring und Jochen Frowein 1981 [65]

Möchte man als zweite Impression zur Konsumkultur am Institut die Feier zur Verabschiedung Hermann Moslers und zur Berufung Karl Doehrings und Jochen Froweins als Direktoren 1981 zum Vergleich heranziehen, so hat sich der Weinverbrauch noch weiter erhöht. Für 200 geladene Gäste wurden 300 Flaschen bereitgestellt – gesponsert von der BASF. Kredenzt wurde zudem ein kaltes Buffet mit englischem Roastbeef, Schweinerücken, Kasseler (mild geraucht), „Truthahn american“, Schweinelendchen mit Kiwi, Schinkenröllchen mit Spargel, gefüllten Eiern, Tomaten mit Thunfisch, Forellenfilets, Geflügelsalat Hawaii, Rindfleischsalat und norwegischer Reissalat (mit Lachs). Als – nach heutigen Maßstäben – vegetarische Elemente des Buffets gelten können: diverse (Blatt-) Salate und das „internationale Käsebrett“ mit Brotbeilage.[66]

Schlacht am Buffet 1968 Kolloquium „Gerichtsschutz gegen die Exekutive [67]

Besonders gut dokumentiert sind die anlässlich der Kolloquien und Festen angerichteten Buffets, die in der visuellen Erinnerungskultur des Instituts einen beträchtlichen Teil einnehmen. Die Bedeutung fotografisch festgehaltener Essensszenen und Speisen erklärt sich historisch aus den gerade erst überwundenen Hungerjahren des Krieges und den (kühltechnisch bedingten) Importmöglichkeiten von bis dato eher unbekannten exotischen Früchten wie Melonen und Bananen, die den Gästen stolz mit Schlagsahne-Bergen dargeboten wurden. Die Bedeutung dieses kulinarischen Überflusses für die Festgesellschaft lässt sich erahnen, wenn man die unlängst erschienenen Aufzeichnungen von Rudolf Bernhardt aus seiner sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenschaft oder die Schilderungen von Karl Doehrings britischer Kriegsgefangenschaft in dessen Autobiographie heranzieht. Doehring berichtet von den fünf Jahren im Zeltlager in der ägyptischen Wüste, dass die „Ernährung (…) immer knapp“ und auch die Trinkwasserversorgung ein Problem war.[68] Im Vergleich zu Rudolf Bernhardt ging es ihm damit noch gut. In der sowjetischen Gefangenschaft war die Ernährungslage derart katastrophal, dass Bernhardt mehrfach kurz vor dem Tod stand und zum Zeitpunkt seiner Entlassung 1947 auf 48 Kilo Körpergewicht abgemagert war:

„Der Hunger ist groß, mancher kann sich nicht beherrschen und schlingt schmutzige und kranke Kartoffelschalen, gefrorenes Kraut oder ähnliche Dinge hinunter, die der geschwächte Magen nicht vertragen kann. Es ist eine traurige Wahrheit, daß einzelne selbst ihren Tod herbeiführen, weil sie den Hunger nicht bezwingen können.“[69]

Vor diesem Hintergrund erscheinen die Fest-Buffets nicht nur als opulent, sondern geradewegs als „schlaraffisch“.

4. „Lass sie doch feiern“. Transgression und Subversion

-

-

-

Theo Völker auf Hochtouren. Rechts zusammen mit Frau Ballreich und Anne Mosler, den Gattinnen des Institutsdirektors bzw. des Generalsekretärs der MPG, 1981 [70]

Das Heidelberger Institut war von seiner sozialen Zusammensetzung im Vergleich zum Berliner KWI zwar „bürgerlicher“, dennoch war es dadurch nicht weniger hierarchisch. Hatten zu Berliner Zeiten das technische und wissenschaftliche Personal überwiegend demselben großbürgerlichen Milieu angehört, rekrutierten sich insbesondere die nicht-wissenschaftlichen Institutsmitarbeiter nun aus dem lokalen Handschuhsheimer Bürgertum. Zwar gab es durch die räumliche Situation im Institutsgebäude in der Berliner Straße und die vordigitalen Arbeitsprozesse, die eine enge Einbeziehung von (vorwiegend weiblichen) Schreibkräften in die (wissenschaftliche) Textproduktion mit sich brachten, eine ausgeprägte Kollegialität und ein Bewusstsein für die gemeinsame Aufgabe. Gleichermaßen gab es, zumindest im Vergleich zu heute, stärkere soziale Hierarchien zwischen Forschenden und Nicht-Forschenden und mitunter auch im Verhältnis zwischen Direktorium und Referenten.[71]

Beispielhaft für die sozial „egalisierende“ Wirkung von Feiern mag der langjährige Hausmeister Theo Völker gelten, der in der Institutsgemeinschaft augenscheinlich eine derart präsente Figur war, dass man scherzhaft sagte, dass Institut sei nach ihm und nicht nach seinem Forschungsgegenstand benannt. Auf den von den Institutsfesten überlieferten Fotos nimmt Theo Völker stets eine prominente Rolle ein. Zeigen ihn Bilder aus dem Alltag des Instituts in blauem Arbeitskittel, so ist er auf Festen, gewissermaßen für einen Abend bewusst aus seiner sozialen Rolle ausbrechend, Arm in Arm mit bedeutenden Professoren oder Gattinnen von Direktoren oder Kuratoriumsmitgliedern herzend, Waldhorn spielend, singend oder mit jungen Referentinnen tanzend zu sehen.[72]

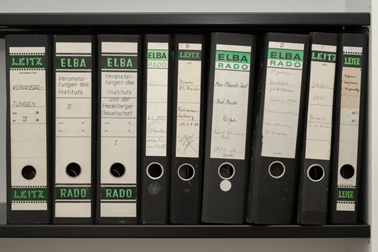

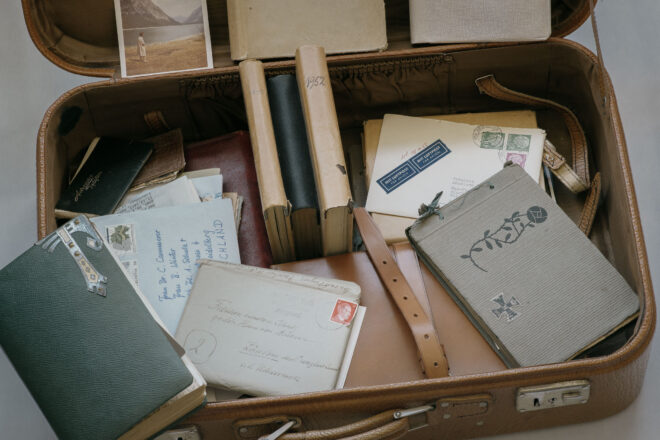

Akribisch dokumentiert: Die Korrespondenzen, Abrechnungen, Fotos und persönlichen Erinnerungen zu Festen und Feiern im Institut umfassen mehr als einen Meter Aktenmaterial [73]

Einen prägenden Einblick in die Heidelberger „Festkultur“ vermittelt die 1995 von Karl Doehring gehaltene, nostalgisch eingefärbte Weihnachtsfeierrede. Doehring gibt einen launigen Rückblick über die zurückliegenden 46 Jahre, denen er ab 1949 als Referent und von 1981 bis 1987 als Direktor dem MPIL angehörte. Statt vierhändiger Klavierkonzerte und Rokoko-Aufführungen wurde am MPIL eine etwas bodenständigere Festkultur gepflegt mit Ziehharmonika, Gitarre, Schlagermusik und etwas Landser-Romantik: „Zum Schluss endeten solche fröhlichen Feste, indem wir alle zusammen die ‚Schildwacht‘ sangen. Die hatte ich eingeführt in solche Feste, als alter Soldat, mich erinnernd an einen großen Teil meines Lebens.“[74] Gerade Doehring schien ausweislich seines Credos „Lass sie doch feiern“ der feierfreudigste und toleranteste Direktor gewesen zu sein.[75]

Karikatur Jochen Frowein (G. Baldini, 1990) [76]

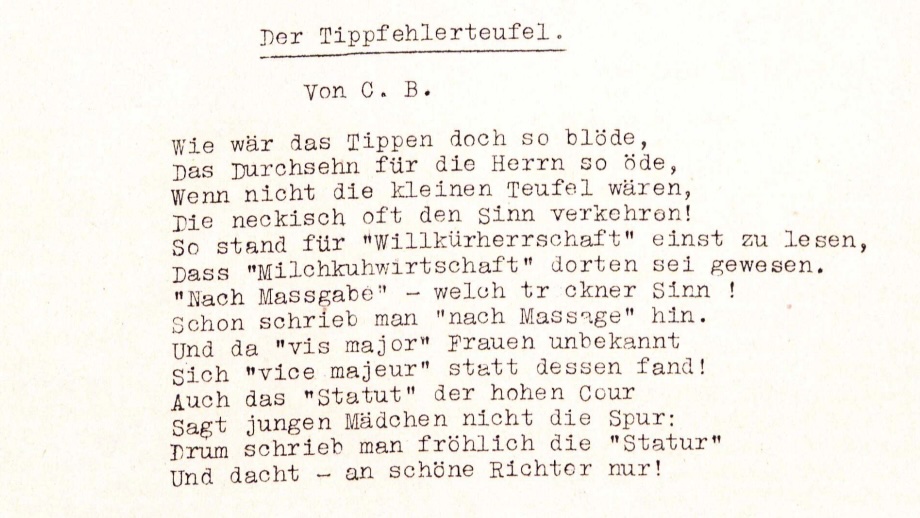

Ein subversives Element, mit dem das Festliche für Momente auch im Alltagskontext der Referentenbesprechung durchbrach, beinhalteten vor allem die zumeist von Matthias Hartwig vorgetragenen Rosenmontagsansprachen[77] bzw. die von vielen Weihnachtsfeiern überlieferten launigen Gedichte bzw. Theaterstücke und die Direktoren überreichten Spaßfestschriften, die Charaktereigenschaften, Institutsbegebenheiten und Mitarbeitende wohlwollend bis satirisch verarbeiten.[78] So wird beispielsweise in der Spaßfestschrift „Heidelberger Menschenrechtskonvention“ (HMRK) zu Jochen Froweins 60. Geburtstag 1994, von Mitarbeitenden ironisch die „Menschenrechtssituation im Institut“ untersucht.[79] Im Zentrum der Festschrift stehen die Zusammensetzung des Instituts und dessen Hierarchien (Referendare sind „noch ungeborenen Kindern“ gleichgestellt, ein „großer Schritt zur Erreichung der Menschwerdung ist der Entschluß zur Habilitation“[80]). Großen Raum nimmt auch die wissenschaftliche Kultur ein, insbesondere in der Referentenbesprechung. Stefan Oeter diskutiert das „Recht auf Referentenbesprechung“, Dominik Lentz reflektiert die Frage von „Mindermeinungsschutz“ in der Referentenbesprechung und Peter Rädler das Recht auf „freie Persönlichkeitsentfaltung“ im Institut. Sind die Beiträge in den Spaßfestschriften für die Direktoren dennoch immer im Rahmen geblieben, sind auch anonyme „Theaterstücke“ überliefert, die, wie man hört, für nachhaltigere Verstimmung im Direktorium und unter Mitarbeitern gesorgt haben, die sich als unzutreffend karikiert empfunden haben.[81] Der Festen eigene „Exzess“ funktioniert also nur, wenn er im Rahmen bleibt und die soziale Ordnung temporär aufhebt, ohne sie in den Grundsätzen infrage zu stellen, ansonsten gilt das Fest als misslungen – ein Punkt, der gerade bei vorgerückter Stunde und steigendem Alkoholkonsum nicht immer leicht zu finden war (und ist).

Für das leibliche Wohl zuständig: Verwaltungsleiterin Margarete Noll verköstigt Konferenzteilnehmer 1964 [82]

Werden auf Festen soziale Rollen zum Teil bewusst aufgehoben, werden sie andererseits auch verfestigt, zum Teil aber auch neu ausgehandelt. Über den Großteil der Institutsgeschichte hinweg war es üblich, dass die Mitarbeiterinnen und Direktorengattinnen für das „Soziale“ zuständig waren. Fast alle Feiern und Feste wurden im Hintergrund maßgeblich von Frauen organisiert und betreut, da der Großteil der Verwaltung zum einen von Frauen besetzt war, zum anderen, da das Zubereiten von Kaffee und Anrichten von Speisen klassisch „gegenderte“ Tätigkeiten waren.

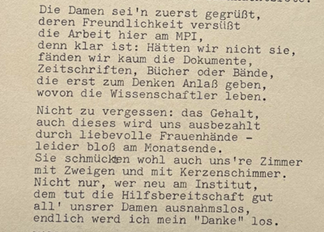

Auszug aus der Weihnachtsansprache 1973

Und so gehörte es auch zu den Aufgaben der damaligen Verwaltungsleiterin Margarete Noll nicht nur den kompletten Institutsetat zu verantworten und auch auf die Kinder des Direktors aufzupassen, sondern auch die Verköstigung von Konferenzteilnehmern zu übernehmen. Gleiches galt für die Ehefrauen der Direktoren, die für die zahlreichen „semi-offiziellen“ Gesellschaftsabende im Privatheim, das als großzügige und repräsentative Dienstwohnung von Seiten der MPG eigens für diesen Zweck zur Verfügung gestellt war, zuständig waren. Aus diesem Grunde war es im Heidelberger Institut über Jahrzehnte Brauch, dass die „Herren“ zu Weihnachten den „Damen“ dankten und sie zur Feier einluden. Eine Praxis, die in den 1980er Jahren als paternalistisch vom weiblichen Personal abgelehnt wurde und fortan verschwand.[83]

IV. Zwischen Internationalisierung und Historisierung. Fest und Feier im 21. Jahrhundert

Feierlich. Die Einweihung des neuen Institutsgebäudes im Neuenheimer Feld 1998 [84]

Mit der Jahrtausendwende gingen für das Institut einige grundlegende Änderungen einher, die nicht nur auf die Zusammensetzung und Arbeit des MPIL, sondern auch auf seine Fest- und Feierkultur großen Einfluss haben sollten. Eine wichtige Zäsur war der Umzug 1997/1998 von der Berliner Straße in das aktuelle Gebäude im Neuenheimer Feld. Statt eines in die Jahre gekommenen und viel zu klein gewordenen Nachkriegsbaus, bezog das Institut nun nicht nur ein größeres, sondern auch repräsentativeres Gebäude. Erstmals erhielt das Institut eine „Heimstätte“, die „aus einem Guss“ auf seine funktionalen Bedürfnisse zugeschnitten war und auch in seiner architektonischen Gestaltung die Bedeutung seiner Aufgabe würdigte. Denn sowohl die Unterbringung im Berliner Stadtschloss als auch im Gebäude in der Berliner Straße waren letztlich Provisorien gewesen, die sich aus den Umständen der Gründung bzw. der Neugründung ergeben hatten. Das Institut im Neuenheimer Feld bot erstmals einen „richtigen“ Lesesaal, auch konnten nun alle Mitarbeitenden im selben Gebäude untergebracht werden, statt wie Jahrzehnte üblich auf MPIL und Max-Planck-Haus verteilt zu sein. Mit dem Umzug war zudem die räumliche Grundlage für das starke Wachstum des MPIL gelegt, das sich in knapp 30 Jahren mit 175 Mitarbeitenden mehr als verdreifacht hat, was 2019 wiederum eine Erweiterung des Gebäudes erforderlich machte.

Der große Konferenzsaal 038 – das 2019 eingeweihte „Herzstück“ des Instituts [85]

Die neue „Repräsentativität“ des Instituts hatte auch Auswirkungen auf die Fest- und Feierkultur. Insbesondere für wissenschaftliche Feierlichkeiten bot das Gebäude nun einen angemesseneren Rahmen, als der Vorgängerbau das vermochte. Viele der wissenschaftlichen Großveranstaltungen hatten bis 1997 aus Platzgründen im Max-Planck-Haus stattfinden müssen. Seit dem Umzug ist das Institut wieder selbst zum Veranstaltungsort geworden. „Herzstück“ der wissenschaftlichen Diskussionskultur waren hierbei immer die Vortrags- und Veranstaltungsräume, in denen die montäglichen Referentenbesprechungen und die Fachveranstaltungen stattfanden und -finden. Im gegenwärtigen Institut ist dies der 2019 eingeweihte große Vortragssaal 038. Dieser trägt nicht nur in der Form seiner ästhetischen Gestaltung der Bedeutung der Referentenbesprechung bzw. der Montagsrunde als dem zentralen wissenschaftlichen Forum des MPIL Rechnung, zugleich weist er durch seine technische Ausstattung auf ein eminent neues „Feature“ der internationalen wissenschaftlichen Fach- und Feierkultur des 21. Jahrhunderts: Digitalität. Durch hybride Konferenztechnik haben sich spätestens seit der „Corona“-Krise neue Formate digitaler Teilhabe aber auch der Aufzeichnung und online Publikation von Vorträgen etabliert, die dem Institut und seinen Feiern eine neue Form von Sichtbarkeit verschaffen.[86]

Doch auch inhaltlich und stilistisch haben sich in der Feierkultur des Instituts im 21. Jahrhundert Änderungen ergeben. Sichtbar wird dies beispielsweise bei der Feier des 100-jährigen Jubiläums im Dezember 2024. Zum ersten Mal seit seinem Bestehen befasste sich das Institut mit seiner Geschichte, statt diese wie bei den vorangegangenen Jubiläen aufgrund ihrer vermeintlichen Problembehaftung zu marginalisieren. Erstmals konstituierte sich die Feiergesellschaft nicht ausschließlich um gegenwärtige Fragen des (Völker-) Rechts, sondern besann sich auch auf die gemeinsame Geschichte als identitätsstiftendes Sammlungsmoment. Wissenschaftliche Zukunftsentwürfe, Gegenwartsarbeit und historische Grundlagen wurden miteinander verknüpft und ganzheitlich gewürdigt und das Institut somit quasi ein Stück weit „vervollständigt“. Auch die künstlerische Ausgestaltung mit Tanz und Musik griff diese „Vervollständigung“ auf verknüpfte die akademische Feier mit dem freien Fest und verband das „Erhabene“ mit dem „Spontanen“.

“La Bamba” statt “Schildwacht”. Internationalisierte Festkultur am Institut 2004 anlässlich der Verabschiedung von Alberta Fabbriccotti[87]

Blickt man auf die „Festkultur“ im Institut, so hat es ebenfalls mit der Jahrtausendwende Änderungen gegeben. Von Seiten der MPG wurden in den letzten 20 Jahren die zuwendungsrechtlichen Regelungen für Feste und Feiern verschärft. So wurden die Mittel für Feierlichkeiten stark gekürzt, was dazu führte, dass (Ehe-) Partnerinnen und Partner von Beschäftigten nicht mehr eingeladen werden können und nicht mehr, wie über Jahrzehnte üblich, als selbstverständlicher Teil der Festgemeinschaft und der erweiterten „Institutsfamilie“ angesehen werden (außer als Selbstzahler). Zudem wurde Alkohol von den Zuwendungsgebern verboten, was zwar gesünder, aber auch puritanischer ist. Das spontane Fest lebt dennoch fort. Zwar ging mit dem starken Wachstum des Instituts ein Teil seiner früheren „Intimität“ verloren, andererseits gewann es durch seine Internationalisierung an neuen Eindrücken und Festformen dazu. Insbesondere die seit mehr als 20 Jahren am Institut präsente lateinamerikanische ICCAL-Community hat sich als festfreudige „driving force“ erwiesen, sodass die „Schildwacht“ am heutigen Institut längst mexikanische Klassiker wie „La Bamba“ ersetzt worden ist. Und das sicherlich nicht zum Nachteil der Stimmung.

V. „Wir haben viel gefeiert.“ – Festkultur im Wandel der Zeit. Ein Fazit

Es geht auch heute noch. Impressionen von der Feier und zum Fest anlässlich des 100-jährigen Institutsjubiläums am 19. Dezember 2024 [88]

In seiner Weihnachtsansprache von 1995 bekundet Karl Doehring: „Ja, wir haben damals viel gefeiert, mehr als heute.“ Diese Aussage hört man als „investigativ“ recherchierender Historiker tatsächlich von Zeitzeuginnen und Zeitzeugen und langjährigen Mitarbeitenden häufiger. Früher habe man mehr und besser gefeiert – doch kann das stimmen?

Das Institut hat sich im Laufe der 100 Jahre seines Bestehens stark gewandelt. Es erlebte Krieg und Zerstörungen, Wiederaufbau und Wirtschaftsaufschwung, Kosmopolitismus und kurpfälzische Gemütlichkeit, Nationalismus und Internationalismus. Die Forschungsschwerpunkte und Arbeitsweisen des Instituts wandelten sich im Laufe der Zeit, die soziale und nationale Herkunft seiner Belegschaft und insbesondere auch seine Größe änderten sich sehr. Das Institut ging stets mit seiner Zeit, ein Gleiches gilt für seine Art zu feiern und Feste zu gestalten. Und so lässt sich festhalten: Auch heute wird am Institut noch gefeiert und dies keinesfalls weniger, nur anders. Jede Zeit hat ihre Fest- und Feierkultur.

Zur Feier: Anders als zu Zeiten des KWI oder des MPIL der 1950er Jahre, als die Niederlagen beider Weltkriege und die Schuld am „Dritten Reich“ und der nationalsozialistischen Verbrechen auf der deutschen Gesellschaft und auch dem Institut lasteten, weiß das Institut spätestens seit den 1960er Jahren, wo es steht und wofür es steht. Die „Unfähigkeit zu feiern“ ist am MPIL unter Hermann Mosler zu einer richtungshaften, zukunftsgewandten Feier der deutschen Völkerrechtswissenschaft und ihres Beitrages für die internationale Wissenschaftsgemeinschaft und zum Zusammenwachsens Europas und der Welt geworden. Hatte man am Institut im Sinne des allgemeinen Zeitgeistes über viele Jahrzehnte seine eigene Geschichte verdrängt, so hat das MPIL sie spätestens zur Feier seines 100-jährigen Bestehens im Dezember 2024 wiederentdeckt und die historische Dimension seines Wirkens und Werdens in seine Feierkultur integriert.

Zum Fest: Auch an Festen mangelt es dem Institut nicht. Doch hat sich auch die Festkultur in den letzten 100 Jahren stark gewandelt. Gegenwärtige Forschungsschwerpunkte des MPIL und am Institut abgehaltene Veranstaltungen wie „Defund Meat“ ebenso wie der persönliche Lebensstil der meisten Institutsangehörigen und Gastforschenden lassen die bis in die 2000er hinein praktizierte fleischlastige Buffetkultur als in gewisser Weise archaisch erscheinen. Auch werden Feste inzwischen durch Komitees organisiert und nicht ausschließlich „Sekretärinnen“ oder Direktorengattinnen und – inzwischen auch existent – Direktorinnengatten aufgebürdet. Doch hat sich insbesondere durch die Größe des Instituts die „Sichtbarkeit“ und auch die Art der Festgemeinschaft gewandelt. Mit mehr als 170 international zusammengesetzten Institutsangehörigen und mehreren Forschungsgruppen sind Feste „komplexer“ geworden als sie es noch vor 30 Jahren waren – und das keinesfalls zum Schlechteren, wie nicht zuletzt die ICCAL-Community unter Beweis stellt.

Wie sich die Fest- und Feierkultur am Institut weiterentwickeln wird, wird die Zukunft zeigen. Sicher ist: solange es ein Institut gibt, wird auch gefeiert werden.

***

Der Verfasser dankt Sarah Gebel, Matthias Hartwig, Alexandra Kemmerer Karin Oellers-Frahm und Joachim Schwietzke für ihre Anmerkungen zum Text. Zudem sei Alberta Fabbricotti für die Überlassung des Videos gedankt.

[1] Philipp Glahé, Die Welt von Gestern. Das Institut und der Zweite Weltkrieg aus Tagebuchaufzeichnungen, MPIL100.de.

[2] Der Verfasser hält es nicht für unwahrscheinlich, dass man am Institut die 1000er-Marke tangieren würde, würde man versuchen, sämtliche größere und kleinere Feierlichkeiten seit 1924 zu erfassen. Rechnet man zusätzlich zur Weihnachtsfeier, zum Betriebsausflug und zum Sommerfest mit einem Dienstjubiläum, einem (runden/größeren) Geburtstag pro Jahr, läge man schon bei 500 Feiern in 100 Jahren. Geht man dann davon aus, dass pro Jahr mehr als ein Geburtstag, mehr als eine akademische Auszeichnung bzw. Abschluss von Promotions- und Habilitationsverfahren begangen wurden und man pro Jahr mit zehn größeren und kleineren Festlichkeiten kalkuliert, wäre man im Schnitt bei ca. 1000 Feiern in 100 Jahren. Wer nun den Eindruck hat, am Institut würde ausschließlich gefeiert: laut Berechnungen des Autors stehen 1000 Feiern ca. 4.400 Referentenbesprechungen gegenüber (Berechnungsgrundlage: für den Zeitraum von 1949 bis 2025 im Durchschnitt 47 von 52 Kalenderwochen mit Referentenbesprechungen und für den Zeitraum von 1930 (Zeitpunkt der Einführung der RB) bis zum Kriegsausbruch 1939 zwei Besprechungen pro Woche – damals dienstags und samstags).

[3] Foto: MPIL.

[4] Otto Friedrich Bollnow, Neue Geborgenheit. Das Problem der Überwindung des Existenzialismus, Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer 1955; Winfried Gebhardt, Fest, Feier und Alltag. Über die gesellschaftliche Wirklichkeit des Menschen und ihre Deutung, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang 1987, 52–53.

[5] Olivier Douville, Fêtes et contextes anthropologiques, Adolescence 3 (2005), 639–648, 645.

[6] Foto: MPIL.

[7] Sigmund Freud, Totem und Tabu. Einige Übereinstimmungen im Seelenleben der Wilden und der Neurotiker, Wien: Hugo Heller 1913, 157.

[8] Roger Caillois, L’homme et le sacré, Paris: Gallimard 1988; Roberta Colbertaldo, Rituelle Inversion und subversive Diskurse. Überlegungen für eine Theorie des Karnevals der Vormoderne aus romantischer Perspektive, Lingue e letterature d’Oriente e d’Occidente 9 (2020), 243–254, 250.

[9] Odo Marquardt, Moratorium des Alltags. Eine kleine Philosophie des Festes, in: Walter Haug/Rainer Warning (Hrsg.), Das Fest, Politik und Hermeneutik Bd. XIV, München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag 1989, 684–691.

[10] Zur Arbeitskultur am MPIL, siehe u.a.: Matthias Hartwig, Das wissenschaftliche Hochamt. Die Referentenbesprechung (vulgo Montagsrunde) am Institut, MPIL100.de; Juliane Kokott, Aus dem Leben des Instituts im Jahre 1987, MPIL100.de oder Torsten Stein, Von Pfeifenrauch und „klingelnden Weckern“. Das Institut in den siebziger und achtziger Jahren, MPIL100.de.

[11] Foto: AMPG.

[12] Alexander Mitscherlich/Margarete Mitscherlich, Die Unfähigkeit zu trauern. Grundlagen kollektiven Verhaltens, München: Piper 1967; Josef Kopperschmidt, Über die Unfähigkeit zu feiern. Allgemeine und spezifisch deutsche Schwierigkeiten mit der Gedenkrhetorik, in: Josef Kopperschmidt/Helmut Schanze (Hrsg.), Fest und Festrhetorik. Zur Theorie, Geschichte und Praxis der Epideiktik, München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag 1999, 149–172.

[13] Philipp Glahé, History as a Problem? On the Historical Self-Perception of the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, ZaöRV 83 (2023), 565–578; Armin von Bogdandy/Philipp Glahé, Alles ganz einfach? Zwei verlorene Weltkriege als roter Faden der Institutsgeschichte, MPIL100.de.

[14] Marie Bruns, Eine „ganz unverhoffte Freude“. Eindrücke aus der Gründungszeit des Instituts 1924–1926, MPIL100.de.

[15] Rüdiger Hachtmann, Das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht 1924 bis 1945, MPIL100.de.

[16] Foto: MPIL.

[17] Zu Carl Bilfinger allgemein: Philipp Glahé/Reinhard Mehring/Rolf Rieß (Hrsg.), Der Staats- und Völkerrechtler Carl Bilfinger (1879–1958), Baden-Baden: Nomos 2024.

[18] Carl Bilfinger, Ansprache, 1953, Ordner „Institutschronik I“, MPIL.

[19] Carl Bilfinger, Prolegomena, ZaöRV 13 (1950), 22–26; ferner: Bogdandy/Glahé, Alles ganz einfach? (Fn. 13).

[20] Foto: MPIL.

[21] Hermann Mosler/Georg Schreiber (Hrsg.), Völkerrechtliche und Staatsrechtliche Abhandlungen: Carl Bilfinger zum 75. Geburtstag am 21. Januar 1954 gewidmet von Mitgliedern und Freunden des Instituts, Köln: Carl Heymanns Verlag 1954.

[22] Glahé/Mehring/Rieß, Carl Bilfinger (Fn. 17), 336–339; zudem: Felix Lange, Überraschende „Entnazifizierung“. Bilfingers Wiederberufung nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, in: Glahé/Mehring/Rieß, Carl Bilfinger (Fn. 17), 405–424; ferner: Katharina Isabel Schmidt, „Von hier bis zu einer Ehrung Carl Schmitts […] sind es nur noch ein paar Schritte“. Ernst Joseph Cohns Kritik an Carl Bilfingers Festschrift 1954, MPIL100.de; Johannes Mikuteit, “Einfach eine sachlich politische Unmöglichkeit“. Die Protestation von Gerhard Leibholz gegen die Ernennung von Carl Bilfinger zum Gründungsdirektor des MPIL, MPIL100.de.

[23] Zu Kaufmann, Jellinek und Partsch: Philipp Glahé, Amnestielobbyismus für NS-Verbrecher. Der Heidelberger Juristenkreis und die alliierte Justiz (1949–1955), Göttingen: Wallstein 2024.

[24] Ernst J. Cohn, [Rezension] Völkerrechtliche und staatsrechtliche Abhandlungen. Carl Bilfinger zum 75. Geburtstag am 21. Januar 1954 gewidmet von Mitgliedern und Freunden des Instituts. Max-Planck-Institut für Ausländisches Oeffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, Berlin 1958, The Modern Law Review 19 (1956), 231–233, 233.

[25] Brief von Ernst J. Cohn an Hermann Mosler, datiert 18. April 1956, zitiert nach: Glahé/Mehring/Rieß, Carl Bilfinger (Fn. 17), 345–348, 346.

[26] Foto: MPIL.

[27] Hermann Mosler, Rede zur Einweihung des Institutsanbaus am 22.11.1959, Ordner „Institutschronik I“, MPIL.

[28] So fanden im Institut folgende Kolloquien statt: „Staat und Privateigentum“ (1959); „Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit der Gegenwart“ (1962); „Haftung des Staats für rechtswidriges Verhalten seiner Organe“ (1967); „Gerichtsschutz gegen die Exekutive“ (1968); „Judicial Settlement of International Disputes“ (1972); „Grundrechtsschutz in Europa“ (1976); „Koalitionsfreiheit des Arbeitnehmers“ (1978). Zu diesen und weiteren Kolloquien siehe: Rudolf Bernhardt/Karin Oellers-Frahm, Das Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht. Geschichte und Entwicklung von 1949 bis 2013, Berlin: Springer 2018, 102–109. Die Ergebnisse der Kolloquien samt Teilnehmernamen wurden zudem in den „Beiträgen zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht“ veröffentlicht.

[29] Foto: MPIL.

[30] Als beispielhaft für die Institutsvorträge zu nennen wären: Edward McWhinney, University of Toronto, „Die Gerichte als Hüter der Verfassung im britischen Commonwealth“ (5. Januar 1961); Giorgio Balladore Pallieri, Richter am EGMR, „Rapports entre le droit international et le droit interne dans les organisations européennes“ (14. Februar 1962); Georg Schwarzenberger, University of London, „Neue Entwicklungen im Internationalen Wirtschaftsrecht“ (1962); Walter Hallstein, Präsident der Kommission der Europäischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft, „Die Europäische Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft – politisch gesehen“ (19. Oktober 1962); Rudolf B. Schlesinger, Cornell Law School, Ithaka, New York, “Die Ermittlung der allgemeinen Rechtsgrundsätze durch Rechtsvergleichung“ (25. Januar 1963); Clive Parry, Cambridge, “Manner in which legal advice is given to departments of the British government having to do with foreign affairs” (27. Mai 1963); Adriano Moreira, Technische Universität Lissabon, „Le Portugal et l’intégration européene“ (10. Juni 1963); Spencer Kimball, University of Michigan Law School, „The Interstate Commerce Clause and Federalism in American Constitutional Law” (7. Februar 1964); Heinrich Hendus, Leiter der Generaldirektion für überseeische Entwicklungsfragen der EWG-Kommission, „Die Europäische Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft und die afrikanischen Staaten“ (22. Februar 1962); Vavro Hajdu, Akademie der Wissenschaften Prag, „Juristische Aspekte der Deutschlandfrage“ (27. Juni 1966); Richard Gardner, Columbia University New York, „The Future of the United States as a Peacekeeping Agency” (29. Juni 1966); Juraj Andrassy, Universität Zagreb, „Aktuelle Rechtsfragen des Festlandsockels” (29. Mai 1967); Ludwik Gelberg, Polnische Akademie der Wissenschaften, „Probleme der völkerrechtlichen Kontinuität der Staaten bei sozialen Umwälzungen im Lichte der polnischen Praxis“ (13. Juli 1967); Shabtai Rosenne, Mitglied der UN-Völkerrechtskommission, Israelischer Botschafter bei den UN, „The First Session of the Conference of the Codification of the Law of Treaties“ (27. Mai 1968); Wladimir Zeltner, Präsident des Gerichtshofs in Tel Aviv, „Das Recht Palästinas und die Grundzüge des kommenden Rechtes des Staates Israel“ (24. März 1969); Harry Silberberg, Salisbury, „Staats- und völkerrechtliche Fragen Rhodesiens“ (2. Februar 1970).

[31] Zu jedem einzelnen Vortrag sind Einladungslisten, Korrespondenzen, Vortragsmanuskripte, vielfach auch Diskussionsprotokolle und Presseberichte überliefert. Zu den größten Veranstaltungen zählte der Vortrag Walter Hallsteins über die politische Rolle der EWG, zu dem 209 Personen eingeladen worden und 136 erschienen waren. Anwesend und eingeladen waren Richter von Bundesverfassungsgericht und BGH, Vertreter aus Lokal-, Landes- und Bundespolitik, Vertreter von MPG und Universitäten sowie Industriemanager aus dem Rhein-Neckar-Raum, die vielfach Mitglied im Kuratorium waren. Hermann Mosler zitierte in seiner Einführung Robert Schuman mit den Worten: „Europa entsteht nicht mit einem Schlag und nicht in einer Gesamtkonstruktion“, und fügte hinzu: „Dieser einfache Satz machte alle Begeisterung für Europa und die neuartige Verschmelzung von Souveränitätsrechten erst realistisch.“ Zum Redner gewandt: „Ihre klare Konsequenz, unbeirrbar im Ziel, elastisch in den Mitteln, ist der Bewunderung würdig. Sie werden ein aufmerksames Auditorium haben“: Hermann Mosler, Ansprache, 19.10.1962, Ordner „Veranstaltungen des Instituts II“, MPIL.

[32] Foto: MPIL.

[33] Armin von Bogdandy/Mariela Morales Antoniazzi, Forschen mit Lateinamerika. Der Weg des MPIL, MPIL100.de.

[34] Foto: MPIL.

[35] Glahé, History as a Problem? (Fn. 13).

[36] Zu Erich Kaufmann ist ein eigener Ordner überliefert, der sämtliche Geburtstags-Korrespondenz, Glückwunschschreiben, Todesanzeigen, Kondolenzkorrespondenz und Nachrufe enthält: Ordner „Professor Kaufmann, 80. Geburtstag, 85. Geburtstag“. Vom Institut wurde eine Festschrift und die Gesamtausgabe seiner Werke mitorganisiert bzw. -finanziert: Um Recht und Gerechtigkeit. Festgabe für Erich Kaufmann zu s. 70. Geburtstage – 21. September 1950 – überreicht von Freunden, Verehrern u. Schülern, Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer 1950; Erich Kaufmann, Gesammelte Schriften. Zum achtzigsten Geburtstag des Verfassers am 21. September 1960, Göttingen: Schwartz 1960; ferner: Karl Josef Partsch, Der Rechtsberater des Auswärtigen Amtes 1950–1958. Erinnerungsblatt zum 90. Geburtstag von Erich Kaufmann, ZaöRV 30 (1970), 223–236.

[37] Zum 70., 75. und 80. Geburtstag gab es größere Geburtstagsfeiern für Makarov, zum 70. überdies eine Festschrift: Festgabe für Alexander N. Makarov, in: Abhandlungen zum Völkerrecht, Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer 1958; Hermann Mosler, Nachruf Alexander N. Makarov (1888–1973), ZaöRV 33 (1973), 443–446.

[38] Rudolf Bernhardt (Hrsg.), Völkerrecht als Rechtsordnung. Internationale Gerichtsbarkeit, Menschenrechte. Festschrift für Hermann Mosler, Berlin: Springer 1983.

[39] Ulrich Beyerlin (Hrsg.), Recht zwischen Umbruch und Bewahrung Völkerrecht, Europarecht, Staatsrecht. Festschrift Für Rudolf Bernhardt, Berlin: Springer 1995.

[40] Torsten Stein (Hrsg.), Die Autorität des Rechts: Verfassungsrecht, Völkerrecht, Europarecht. Referate und Diskussionsbeiträge des wissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums aus Anlaß des 65. Geburtstages von Karl Doehring am 17. März 1984 in Heidelberg, Heidelberg: v. Decker & Müller 1985; Kay Hailbronner/Georg Ress/Torsten Stein (Hrsg.), Staat und Völkerrechtsordnung: Festschrift für Karl Doehring, Berlin: Springer 1989; Kay Hailbronner (Hrsg.), Die allgemeinen Regeln des völkerrechtlichen Fremdenrechts. Bilanz und Ausblick an der Jahrtausendwende. Beiträge anläßlich des Kolloquiums zu Ehren von Prof. Dr. Karl Doehring aus Anlaß seines 80. Geburtstags am 17. März 1999 in Konstanz, Heidelberg: C.F. Müller 2000.

[41] Hans-Joachim Cremer (Hrsg.), Tradition und Weltoffenheit des Rechts: Festschrift für Helmut Steinberger, Berlin: Springer 2002.

[42] Rüdiger Wolfrum, Jochen Abr. Frowein Zum 70. Geburtstag, AÖR 3 (2004), 330–332; zudem: Kolloquium aus Anlass des 80. Geburtstags von Prof. Dr. Dres. h. c. Jochen Abr. Frowein, Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, Heidelberg, 21. Juni 2014, ZaöRV 75 (2015), 713–868.

[43] Leider gibt es auf der Institutshomepage keine Beschreibung oder Darstellung der Lectures und ihrer Geschichte und Bedeutung, dennoch lassen sich die Lectures selbst über den Youtube-Kanal des Instituts anschauen.

[44] Foto: MPIL.

[45] Max Planck (Hrsg.), 25 Jahre Kaiser Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, Bd. 1: Handbuch, Berlin: Springer 1936, 194–195.

[46] Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (Hrsg.), Tätigkeitsbericht für das Jahr 1999, 51–52.

[47] VI. Abt., Rep. 1, Nr. KWIauslöffRechtuVölkerrecht III/42.

[48] Carlo Schmid, Erinnerungen, Bern: Scherz 1979, 121.

[49] Schmid (Fn. 48), 122; 132; 133.

[50] Philipp Glahé, Eine Frage der Klasse. Die Sekretärinnen des Instituts 1924–1997, MPIL100.de; Philipp Glahé, Die Welt von Gestern. Das Institut und der Zweite Weltkrieg aus Tagebuchaufzeichnungen, MPIL100.de.

[51] Von links, stehend: Sibille von Haeften (verdeckt), Marie und Viktor Bruns, Fräulein Kuhlmann (spätere Kweske), Luise Grubener, Irmgard von Lepel, Irene Haehn, Annelore Schulz, Else Sandgänger, Hella Bruns, Auguste Maginen; vorne, von links: Ellinor Greinert, Ilse und Sidonie von Engel, Lise Rapp, Charlotte Zowe-Behring. Quelle: VI. Abt., Rep. 1, Nr. KWIauslöffRechtuVölkerrecht III/13.

[52] Ellinor Greinert, Der Jahrestag der Thronbesteigung. Eine unzeremoniöse Szene am Hofe des Fürsten Carolus des Siegreichen, unveröffentlichtes Typoskript, 1934, Privatarchiv Rainer Noltenius.

[53] Gerhard Dannemann, Marguerite Wolff at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, MPIL100.de; Nathalie Le Bouëdec, Hermann Heller, der Außenseiter. Kritiker und Verteidiger des Rechtsstaates in einer Krisenzeit, MPIL100.de.

[54] Samuel Salzborn, Hermann Raschhofer als Vordenker eines völkischen Minderheitenrechts, MPIL100.de; Reinhard Mehring, Polykratie der Völkerrechtler. Carl Schmitt, Viktor Bruns und das KWI für Völkerrecht, MPIL100.de.

[55] Von links: Gertrud Heldendrung, Sibille von Haeften, Cornelia Bruns, Lise Rapp (stehend), Maria Heldendrung, Ellinor Greinert; vorne links: Annelore Schulz. Aufnahme: 17.02.1935, Fotografin: Lore Feininger, Berlin, VI. Abt., Rep. 1, Nr. KWIauslöffRechtuVölkerrecht III/23.

[56] Greinert, Der Jahrestag der Thronbesteigung (Fn. 52),1–11; 3.

[57] Cornelia Bruns/M. Petrich/Liese Rapp (Hrsg.), Spaß-Festschrift Institutsjubiläum 1934, unveröffentlichtes Typoskript; ferner: Glahé, Eine Frage der Klasse (Fn. 50).

[58] Bild links: Rainer Noltenius (Hrsg.), Mit einem Mann möchte ich nicht tauschen. Ein Zeitgemälde in Tagebüchern und Briefen der Marie Bruns-Bode (1885–1952), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag 2018, 144; Bild rechts: Wikimedia.

[59] Noltenius, Mit einem Mann möchte ich nicht tauschen (Fn. 58), 143.

[60] Vgl. Bildinformation VI. Abt., Rep. 1, Nr. KWIauslöffRechtuVölkerrecht III/23.

[61] Foto: AMPG.

[62] Karl Doehring, Eine „besondere Vergangenheit“, zitiert nach: Philipp Glahé, Das Institut als Idyll. Karl Doehrings Weihnachtsansprache 1995, MPIL100.de, 1–21, 9.

[63] Foto: MPIL.

[64] Rechnung Stadthallen Gaststätten, 26.06.1954, Ordner „Institutschronik I“, MPIL.

[65] Foto: MPIL.

[66] Ordner „Institutschronik III“, MPIL.

[67] Foto: MPIL.

[68] Karl Doehring, Von der Weimarer Republik zur Europäischen Union. Erinnerungen, Berlin: WJS Verlag 2008, 103.

[69] Rudolf Bernhardt, Tagebuchaufzeichnungen aus sowjetischer Kriegsgefangenschaft 1945–1947, hrsg. von Christoph Bernhardt, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag 2024, 34.

[70] Foto: MPIL.

[71] Vgl.: Hartwig, Das wissenschaftliche Hochamt (Fn. 10).

[72] Auch Theo Völkers Vorgänger Herr Blum hatte gewisse „Schwierigkeiten“, sich in seine soziale Rolle am Institut einzufinden, wie Karl Doehring 1995 berichtete: Hausmeister Blum habe sich zu besonderen Anlässen wie den Kuratoriumssitzungen „seinen besten Sonntagsanzug angezogen mit Nadelstreifen“ und am Haupteingang alle Mitglieder des Kuratoriums persönlich begrüßt. „Und wenn die Herren vom Kuratorium, die großen Herren, alle kamen, jeder gab ihm die Hand und sagte: ‚Guten Tag, Herr Kollege.‘ Ich habe gesagt: ‚Herr Blum, so geht das nicht weiter, Sie können sich da nicht mehr hinstellen oder ich muss Ihnen eine Hausmeistermütze kaufen. Denn die Herren wundern sich doch, wenn nachher eine Kuratoriumssitzung ist und dieser Kollege ist dann gar nicht dabei, der sie da unten begrüßt hat.‘“: Doehring, Eine „besondere Vergangenheit“ (Fn. 62), 13.

[73] Foto: Mirko Lux.

[74] Doehring, Eine „besondere Vergangenheit“ (Fn. 62), 19.

[75] Doehring, Eine „besondere Vergangenheit“ (Fn. 62), 13.

[76] Juliane Hilf/Georg Nolte/Stefan Oeter/Christiane Philipp/Christian Walter, Heidelberger Menschenrechtskonvention. HMRK-Kommentar. Festschrift für Jochen Abr. Frowein, unveröffentlichtes Manuskript, 1990, MPIL.

[77] Der Verfasser äußert den Wunsch, dass Matthias Hartwig seinen Rosenmontagsreden-Vorlass dem Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft bzw. der Institutsbibliothek vermachen möge, um sie der Nachwelt zu erhalten.

[78] „Erschienen“ sind: Ulrich Beyerlin/Lothar Gündling/Rainer Hofmann/Werner Meng/Karin Oellers-Frahm, Enzyklopädie des Max-Planck-Instituts für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht. Publiziert unter den Auspizien der Mitarbeiter des Instituts aus Anlass des 60. Geburtstages von Rudolf Bernhardt 1985, unveröffentlichtes Typoskript, MPIL; Hanns Michael Hahn/Matthias Herdegen/Karin Oellers-Frahm/Torsten Stein, Fontes Vitae Curia Caroli. Karolingisches Hof- und Hausbrevier. Karl Doehring anlässlich des Ausscheidens aus dem Direktorium des Max-Planck-Instituts für ausländisches öffentliches Recht, unveröffentlichtes Typoskript, 1987, MPIL.

[79] Ulrich Beyerlin, Bericht über die Menschenrechtssituation im Institut, in: Spaßfestschrift Frowein (Fn. 76), 89–90.

[80] Karin Oellers-Frahm, Artikel 1. Geltungsbereich, in: Spaßfestschrift Frowein (Fn. 76), 5–10; 7; 8.

[81] Anonym überlieferte Personenaufstellung eines Theaterstücks zur Weihnachtsfeier, 1984, MPIL.

[82] Fotos: MPIL.

[83] Diese Praxis ist auch aus anderen Instituten überliefert: Birgit Kolboske, Hierarchien. Das Unbehagen der Geschlechter mit dem Harnack-Prinzip. Frauen in der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Studien zur Geschichte der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft Bd. 7, Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Rupprecht 2023, 100.

[84] Foto: MPIL.

[85] Foto: MPIL.

[86] Siehe hier v.a. den Youtube-Kanal des Instituts.

[87] Video: Alberta Fabbricotti.

[88] Fotos: MPIL.

Philipp Glahé ist akademischer Rat auf Zeit am Lehrstuhl für Neueste Geschichte und Zeitgeschichte am Historischen Seminar an der LMU München. Von 2022 bis 2025 war er wissenschaftlicher Referent am MPIL. Er ist Mitherausgeber von mpil100.de.