Une réflexion sur l’utilisation du français dans l’étude et la pratique du droit (à l’institut Max Planck de droit international public de Heidelberg et au-delà)

La langue est la clef de voûte de toute pensée et pratique juridique.[1] En effet, elle constitue l’outil de travail central de tout·e juriste, car elle lui permet de forger des idées, de présenter des arguments et, plus largement, de (re-) calibrer le cadre juridique. En d’autres termes, l’expertise d’un·e juriste se mesure aussi à son aisance linguistique. L’importance de cette aisance linguistique s’explique par l’ambiguïté des règles juridiques (internationales), comme nous le rappelle Guy de Lacharrière, ancien juge français à la CIJ, dans son ouvrage classique « La politique juridique extérieure » paru en 1983.

La langue – plus qu’un (simple) outil de travail

Il serait toutefois réducteur de penser la langue uniquement comme un outil. Elle est bien plus que cela. La langue imprègne profondément notre identité et offre un référentiel socio-culturel qui dépasse son caractère nominatif. Comme disait Albert Camus : « Oui, j’ai une patrie : la langue française. » Ainsi, la langue représente également un important vecteur d’identité et de culture, y compris dans le domaine juridique. Compte tenu de cette caractéristique identitaire et culturelle, le choix d’une langue plutôt que d’une autre a un impact significatif sur la pensée et la pratique juridiques.

Lorsque vous lisez le même arrêt en français et en anglais, par exemple, vous constaterez assez vite que les textes respectifs ne divergent pas seulement sur le plan linguistique, mais qu’ils véhiculent également une culture juridique différente, parfois même une conception différente du droit. Prenons par exemple l’arrêt Les Verts de la Cour de justice des Communautés européennes (CJCE) de 1986. Le texte français de l’arrêt fait référence à une « communauté de droit » (transformée plus tard en « Union de droit »), tandis que la version anglaise se réfère à une « Community [Union] based on the rule of law ». Nous savons tous que la notion d’Etat de droit, adaptée par la Cour à la construction européenne (c’est-à-dire à la communauté puis l’Union) et qui est chère aux systèmes de droit civil, d’une part, et le concept de rule of law émanant des systèmes juridiques de la common law, d’autre part, diffèrent à bien des égards. Penser que les langues (du droit) sont tout simplement interchangeables relève du mythe de l’équivalence linguistique, comme le démontre habilement Jacqueline Mowbray. En conséquence, l’utilisation d’une langue peut ouvrir à son utilisateur non seulement un champ lexical, mais aussi et surtout un champ conceptuel et intellectuel, qui peut même revêtir d’une dimension juridico-politique.

Pour des raisons historiques, le français occupe une place particulière dans le droit international et dans le droit de l’Union européenne (UE). Jusqu’à nos jours, cela se traduit par le fait que le français est l’une ou, dans certains cas, la seule langue de travail au sein d’importantes institutions juridiques internationales (en ordre alphabétique : CEDH, CIJ, CJUE, CPI, TPIR, TPIY). La dimension linguistique du procès judiciaire soulève, par ailleurs, aussi des questions de justice linguistique. Le français est également la langue de travail d’un bon nombre d’institutions internationales, y compris le Secrétariat des Nations unies, ainsi que d’enceintes académiques, telles que l’Institut de Droit International. Bien que certains puissent considérer ce privilège linguistique comme désuet, il n’en demeure pas moins qu’il perdure et qu’il imprègne le droit international et le droit de l’UE. En effet, la langue de travail est étroitement liée à la langue de raisonnement, ce qui signifie que le raisonnement se déroule dans un cadre juridique donné (le cas échéant francophone, voire très souvent français). Et sans faire l’éloge du droit français, il est indéniable qu’il a laissé, notamment à travers le Code napoléonien, des traces significatives dans nombre d’autres systèmes juridiques en Europe et au-delà. Ainsi, savoir parler, lire et écrire le français reste pour plusieurs raisons un atout pour tout « internationaliste », « européaniste » ou « (publiciste) comparatiste ».

Le déclin du (droit) français à l’institut de Heidelberg

Dans les années 1950 et 1960, le français était encore l’une des principales langues étrangères parlées à l’institut. Deux brochures en témoignent, présentant l’institut et son travail

Malgré cette importance (relative) de la langue française pour la pratique du droit international et européen, le français tout comme le droit francophone sont rares à l’institut Max Planck de droit international public (MPIL) à Heidelberg. Pour arriver à cette conclusion, j’ai plongé – avec l’aide de ma courageuse assistante (étudiante) – dans les très riches archives de l’institut qui couvrent les 100 dernières années. Nous avons notamment étudié les protocoles de la réunion du lundi (Referentenbesprechung), cherché dans les registres des revues et des bibliothèques les publications des chercheurs de l’institut parues en français ou sur le droit francophone, déchiffré l’écriture de Victor Bruns dans sa correspondance francophone avec ses pairs, décortiqué les agrafes des papiers d’avis juridiques, recueilli les témoignages des (anciens) chercheuses et chercheurs de l’institut, et tourné de nombreuses pages de divers rapports d’activité. Cette exploration des archives n’est pas exhaustive (et sans doute pas exempte d’erreurs statistiques), mais elle apporte des éclairages tout à fait intéressants.

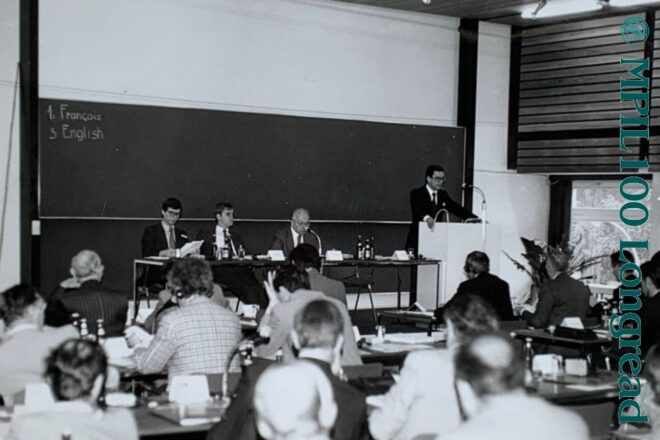

Bon vieux temps ? Hermann Mosler et Suzanne Bastid, première femme professeure de droit en France, lors de la conférence « Judicial Settlement » à Heidelberg en 1972 [2]

Hormis quelques conférences liant des membres de l’institut à des collègues et institutions universitaires francophones, les points de contacts avec la communauté juridique francophone restent sporadiques, même si le cadre institutionnel y est, tel que le partenariat académique franco-allemand HeiParisMax, mis en place en 2015. Bien plus nombreux sont, en effet, les échanges et collaborations scientifiques avec des chercheurs et institutions hispanophones, italophones et bien sûr anglophones.

Il est également à noter que très peu de personnes francophones viennent poursuivre ou approfondir leurs recherches à l’institut, ce qui explique aussi la faible activité du Forum francophone avec en moyenne une à deux présentations par an : les statistiques officieuses de notre « international officer » Mme Stadler montrent qu’en moyenne annuelle, seul·e·s quatre scientifiques, dont la langue de travail est le français, fréquentent la salle de lecture de l’institut ou œuvrent au MPIL en tant que scientifique invité·e, ce qui est cinq fois moins que dans les années 1990s selon les Tätigkeitsberichte (rapports d’activité) de l’époque. Cela contraste aussi significativement avec plusieurs dizaines de chercheurs hispanophones et des centaines d’anglophones aujourd’hui. Il convient toutefois de noter que, par le passé, deux membres francophones ont fait partie du comité scientifique consultatif (Fachbeirat), à savoir Pierre Pescatore, juge à la CJCE, dans les années 1970, et Evelyne Lagrange, professeur à la Sorbonne, dans les années 2010. (Cette dernière est encore aujourd’hui un membre scientifique externe de l’institut.)

De même, la France et son ordre juridique tout comme les ordres juridiques francophones sont (devenus) plutôt rares en tant qu’objets d’études à l’institut de Heidelberg. En témoigne la faible fréquence des présentations sur l’actualité juridique francophone dans le cadre de la Montagsrunde (autrefois appelée Referentenbesprechung), qui se limitent actuellement à une ou deux interventions annuelles au maximum (voir table 1 ci-dessous). Cela signifie que l’actualité juridique dans des ordres juridiques francophones, y compris la France, la Belgique, une partie la Suisse ainsi que toute l’Afrique francophone (couvrant le Maghreb et une bonne partie de l’Afrique subsaharienne), ne trouvent pratiquement aucun écho dans l’institut – alors qu’il y aurait suffisamment de sujets à traiter. Mais les coups d’Etats qui s’enchainent dans la région du Sahel restent, par exemple, relativement inaperçus (ou en tout cas sans suivi académique) à l’institut.

| Année |

Nombre de présentation concernant des questions de droit français |

| 2023 |

2 (portant sur des affaires devant la CEDH contre la France) |

| 2022 |

0 |

| 2021 |

1 (portant sur une affaire devant la CIJ impliquant la France) |

| 2020 |

2 |

| 2019 |

2 (dont 1 portant sur une affaire devant la CJUE contre la France) |

| 2018 |

2 (dont 1 portant sur une affaire devant la CIJ impliquant la France) |

| 2017 |

1 |

| 2016 |

2 |

| 2015 |

1 |

| 2014 |

1 (portant sur une affaire devant la CEDH contre la France) |

| 2013 |

2 |

| 2012 |

1 |

| 2011 |

0 |

| 2010 |

2 |

| 2009 |

1 (portant sur une affaire devant la CEDH contre la France) |

| 2008 |

5 (dont 1 portant sur une affaire devant la CIJ contre la France et 1 portant sur une affaire devant la CEDH contre la France) |

| 2007 |

6 (dont 1 portant sur une affaire devant la CEDH contre la France) |

| 2006 |

7 |

| 2005 |

5 (dont 1 portant sur une affaire devant la CEDH contre la France et 1 portant sur une affaire devant la CJUE contre la France) |

| 2004 |

2 |

| 2003 |

3 (dont 1 portant sur une affaire devant la CIJ contre la France) |

Table 1. Présentations délivrées durant la Referentenbesprechung sur des sujets de droit français (au sens large)

Une exception à l’invisibilité du droit français et de l’actualité juridique francophones réside dans les contributions de collègues francophones à des ouvrages collectifs à vocation comparative, notamment dans le cadre du projet Ius Publicum Europeum. Cependant, ces publications sont rédigées en allemand ou en anglais. En revanche, les publications en langue française sont (désormais) également très rares. Si l’on consulte la liste des publications d’il y a vingt ou trente ans, la situation était encore différente. L’institut publia, par exemple, à des intervalles réguliers des recueils trilingues (allemand, français, anglais) dans la Schwarze Reihe jusqu’à la fin des années 1980. En effet, entre 2002 et 2021, la Schwarze Reihe ne comptait aucune publication en langue française. Aujourd’hui, en moyenne une publication et demie en langue française (tous types de publications – article, chapitre, blog – confondus) par an est publiée par l’un·e des 50 scientifiques de l’institut. Depuis 2000, un seul article en langue française a été publié dans la Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (ZaöRV) sur une question de droit mauritanien. La situation est plus favorable pour la Revue d’histoire du droit international/ Journal of the History of International Law, dont les dernières contributions en français datent de 2020. Des articles en langue allemande (ou anglaise) traitant du droit français, voire francophone parus dans ces deux revues se comptent sur les doigts de deux mains. Il y a toutefois eu quelques recensions de monographies et d’ouvrages collectifs publiés en langue française. Tout bien considéré, le français est donc aujourd’hui loin d’être une langue de recherche, et encore moins une langue de travail (même tertiaire, après l’allemand et l’anglais) à l’institut heidelbergeois.

Analyse des pratiques et compétences linguistiques

Télégramme du président de la Cour d’arbitrage germano-polonaise Paul Lachenal à l’arbitre allemand Viktor Bruns. La correspondance et le travail de la cour se faisaient exclusivement en français

Cette réalité linguistique contraste sensiblement avec la situation antérieure. Dans l’entre-deux-guerres, par exemple, le directeur Viktor Bruns traitait exclusivement en français les cas liés au Tribunal arbitral mixte germano-polonais résultant des dispositions du Traité de paix de Versailles, dont il faisait partie. Puis, directeurs Hermann Mosler – en tant que juge à la CEDH (1959-80) et à la CIJ (1976-85) – et Jochen Frowein – en tant que membre de la Commission européenne des droits de l’Homme à Strasbourg (1973-93) – ont mené une grande partie de leurs activités (para-) judiciaires en français.

Il faut également mentionner que les chercheurs de l’institut ont habituellement rédigé des rapports et avis ayant un lien avec le droit français. En exceptant tous les avis sur la Communauté européenne du charbon de de l’acier (CECA) et sur la poursuite de l’intégration européenne, sur des sujets concernant le droit de la guerre, sur le Conseil de l’Europe qui avaient (également) un lien avec la France ainsi que tous les avis de droit comparatif, on peut trouver, de 1949 à 1998, 13 avis portant exclusivement sur des questions de droit français, dont les deux tiers ayant été rédigés dans les années 1950 (voir table 2 ci-dessous). Mais ces activités d’expertise semblent avoir pris fin depuis 1998, date à laquelle le dernier avis, rédigé par Jochen Frowein et Matthias Hartwig sur la situation juridique des biens culturels saisis ou expropriés par la France, fut produit.

| Année |

Intitulé [avec traduction en français] |

Auteur·e·s |

| 1998 |

Rechtslage der von Frankreich beschlagnahmten bzw. enteigneten Kulturgüter [Situation juridique des biens culturels saisis ou expropriés par la France] |

Jochen A. Frowein and Matthias Hartwig |

| 1997 |

Vereinbarkeit des Gesetzes über die Rechtsstellung der Banque de France mit dem EG-Vertrag [Compatibilité de la loi sur le statut de la Banque de France avec le traité CE] |

Jochen A. Frowein, Peter Rädler, Georg Ress and Rüdiger Wolfrum |

| 1981 |

Rücknahme und Widerruf von begünstigenden Verwaltungsakten in Frankreich, Großbritannien, Italien und den Niederlanden [Retrait et révocation d’actes administratifs favorables en France, au Royaume-Uni, en Italie et aux Pays-Bas] |

Karin Oellers-Frahm, Rudolf Dolzer, Rolf Kühner, Hans-Heinrich Lindemann and Werner Meng |

| 1962 |

Entschädigungssache des Herrn Jaques Sztern, Paris/ Land Nordrhein-Westfalen [Affaire d’indemnisation de M. Jaques Sztern, Paris/ Land de Rhénanie du Nord-Westphalie] |

Fritz Münch |

| 1957 |

Communauté de Navigation Française Rhénane – Land Rheinland-Pfalz betr. Staatshaftung [Communauté de Navigation Française Rhénane – Land de Rhénanie-Palatinat concernant la responsabilité de l’Etat] |

Günther Jaenicke |

| 1956 |

Welches Erbrecht ist beim Tode eines aus rassischen Gründen emigrierten früheren deutschen Staatsangehörigen, der in Frankreich lebte und in Auschwitz ums Leben kam, von dem deutschen Nachlaßgericht für die Erteilung eines gegenständlich beschränkten Erbscheines anzuwenden? [En cas de décès d’un ancien ressortissant allemand émigré pour des raisons raciales, qui vivait en France et qui est mort à Auschwitz, quel droit successoral doit être appliqué par le tribunal successoral allemand pour la délivrance d’un certificat d’héritier limité à l’objet de la succession ?] |

Günther Jaenicke |

| 1956 |

Der Rentenanspruch des unehelichen Kindes eines in französischen Diensten gefallenen deutschen Fremdenlegionärs gegen den französischen Staat [Le droit à pension de l’enfant illégitime d’un légionnaire allemand mort au service de la France contre l’Etat français] |

Günther Jaenicke |

| 1955 |

Zulässigkeit des Elsässischen Rheinseitenkanals [Licéité du Canal latéral du Rhin en Alsace] |

Günther Jaenicke |

| 1954 |

Die völkerrechtliche und staatsrechtliche Stellung des Saargebietes [Le statut de la Sarre en droit international et en droit public] |

Carl Bilfinger, Günther Jaenicke and Karl Doehring |

| 1953 |

Die völkerrechtliche und staatsrechtliche Lage des Saargebietes [Le statut de la Sarre en droit international et en droit public] |

Günther Jaenicke and Karl Doehring |

| 1952 |

Die Stellung des Saargebietes als assoziiertes Mitglied des Europarates [La position de la Sarre en tant que membre associé du Conseil de l’Europe] |

Günther Jaenicke |

| 1951 |

Bürger und Wehrmacht in Frankreich [Les citoyens et la Wehrmacht en France] |

Hans Ballreich |

| 1951 |

Die rechtliche Stellung der politischen Parteien in Frankreich [Le statut juridique des partis politiques en France] |

Günther Jaenicke |

Table 2. Avis portant sur des questions de droit français rédigés par des chercheurs et chercheuses du MPIL

Comment expliquer alors cette faible intensité, voire ce manque d’intérêt pour la langue française à l’institut de Heidelberg ou même pour le droit francophone de nos jours ? La raison pour cette évolution est sans aucun doute multifactorielle. Une première explication, qui semble la plus logique, pourrait résider dans la baisse des compétences linguistiques parmi les chercheurs et chercheuses de l’institut. En fait, de nombreux membres de l’institut étaient francophones (et souvent aussi francophiles) dans l’entre-deux-guerres tout comme après la seconde guerre mondiale. Ceci est vrai pour les scientifiques, mais également pour leurs secrétaires polyglottes. Quelle est la situation aujourd’hui ? L’hypothèse d’une diminution des compétences linguistiques ne tient pas la route : si l’on fait l’inventaire linguistique du personnel scientifique de l’institut, on s’aperçoit que plus de la majorité des chercheurs employés par l’institut ont effectué une période de leurs études en France (ou dans la partie francophone de la Suisse ou du Canada) et ont parfois même obtenu un diplôme d’une université francophone. Ils sont donc tout à fait disposés à suivre les évolutions juridiques dans l’espace francophone. Le recul de l’utilisation du français à l’institut ne peut donc guère s’expliquer par une moindre compétence linguistique. Par ailleurs, les directeurs actuels – Anne Peters et Armin von Bogdandy – ont, eux aussi, une maitrise distinguée de la langue française dont ils font preuve régulièrement lors d’événements francophones.

L’hégémonie anglophone

La langue française perdure dans le système de classement de la bibliothèque, introduit en 1924. Les cotes des pays pour les revues spécialisées sont toujours françaises : les revues américaines se trouvent sous EU (États Unis)

Une autre hypothèse pourrait être que l’usage modéré du français et l’étude limitée du droit francophone à l’institut ne font que refléter le contexte politico-juridique plus large, et donc l’importance décroissante du français dans la pratique juridique internationale. Le français joue un rôle particulier en droit international parce que – pour simplifier – la France était une grande puissance (coloniale) lors de la création de l’ordre juridique international. Par conséquent, une grande partie de la diplomatie internationale se déroulait autrefois en français et les instruments juridiques internationaux étaient également rédigés en français. En témoigne, par ailleurs, les recueils de traités et de jurisprudence publiés, voire édités par des membres de l’institut. On peut citer ici le Nouveau recueil général de traités et autres actes relatifs aux rapports de droit international (Recueil Martens) (publié par l’institut de 1925 à 1969) ou encore le Fontes iuris gentium (publié par l’institut de 1931 à 1990), ce dernier étant passé entièrement en anglais en 1986 (sous le nom de World Court Digest).

Bien que la France conserve un siège permanent au Conseil de sécurité des Nations unies et qu’elle reste un pilier du projet européen, elle n’occupe plus depuis quelque temps le rang de grande puissance. Cela se répercute évidemment sur l’usage de la langue française, en recul, pour ne pas dire en chute libre, au profit de l’anglais, devenu depuis la seconde guerre mondiale la lingua franca des relations internationales. Pour l’anecdote, le traité d’Aix-la-Chapelle – signé par la France et l’Allemagne en 2019 – a d’abord été élaboré et négocié en anglais par les diplomates des deux pays, avant d’être traduit en français et en allemand. Le monde diplomatique évolue et, avec lui, les habitudes linguistiques.

Cela nous amène à un troisième facteur qui peut nous aider à comprendre le recul de la langue française à l’institut de Heidelberg : l’anglophonisation du monde de la recherche, y compris dans le domaine du droit. Pour les internationalistes, européanistes ou encore les publicistes comparatistes, l’anglais est aujourd’hui la première langue d’interaction et surtout la langue de publication dominante, voire écrasante. Il suffit de regarder la liste de revues académiques les plus citées en droit international qui sont toutes, sans exception, anglophones. Malgré le fait que nous puissions aujourd’hui, grâce aux outils numériques, consulter beaucoup plus facilement des sources en plusieurs langues et traduire les écrits de nos collègues, nous constatons depuis une vingtaine d’années que les universitaires se réfèrent principalement et de plus en plus à des sources anglophones. Cela vaut en droit international, comme l’avait déjà en 1988 déploré Allain Pellet dans une lettre aux éditeurs de l’American Journal of International Law (AJIL), ou en droit européen comme le montre l’analyse éclairante de Daniel Thym de 2016. Ce biais linguistique pour l’anglais est, par ailleurs, tout particulièrement prononcé chez les auteurs américains qui, dans les mots de Christian Tomuschat (reproduits ici en français), « restent délibérément dans la cage de la littérature anglophone sans jamais regarder au-delà de leurs propres sources ». Même si les outils tels que DeepL ou ChatGTP nous permettraient d’aborder plus facilement des sources en langue étrangère, leur utilisation peut compléter une expertise linguistique de base, mais ne la remplace pas. En outre, les outils numériques favorisent souvent l’anglais en raison des algorithmes qui les alimentent – mais c’est encore un autre débat.

Le français a donc été remplacé non seulement comme langue de la diplomatie internationale et donc de la pratique du droit international, mais aussi comme langue de la recherche en droit international (et européen). Un changement particulièrement radical et significatif à cet égard fut l’abolition du français comme langue de publication du European Journal of International Law en 1998, lorsque la revue est passée sous la gestion de la maison d’édition britannique Oxford University Press, seulement dix ans après son lancement comme journal bilingue (français/ anglais) par des académiques polyglottes.

En tout état de cause, la situation à l’institut Max Planck heidelbergeois n’est donc pas une exception, mais s’inscrit dans une certaine évolution linguistique. Autrement dit, nous pouvons constater que la mondialisation et la diversification du monde de la recherche affaiblit le français. Suivant cette logique, la question est plutôt de savoir si les derniers bastions de la langue françaises – notamment l’Institut de Droit International – vont pouvoir imposer leur politique linguistique francophone dans la durée, surtout si l’on tient compte du fait que certaines discussions s’y tiennent déjà en langue anglaise, comme me l’a confié Anne Peters, membre de cette institution depuis 2021.

Facteurs aggravants : obstacles académiques et politiques

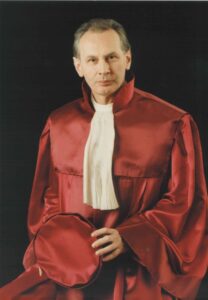

Chercheurs allemands et français côte à côte. Karl-Josef Partsch (à gauche) et Jean-Maurice Verdier (à droite) en 1978 lors du colloque “Koalitionsfreiheit des Arbeitnehmers”[3]

Les caractéristiques particulières du milieu universitaire français du droit (international), marqué par un formalisme très prononcé et une méthode bien distincte (mentionnons ici seulement le plan en deux parties/ deux sous-parties), ne rendent pas nécessairement la recherche juridique émanent de la tradition française facilement accessible. Pourtant, comme l’a démontré avec grande finesse analytique Andrea Hamann, la tradition française du droit international (et, dans une certaine mesure aussi du droit européen) fait preuve d’un pragmatisme. Ce pragmatisme inspirant, voire rafraîchissant pour certains, pourrait s’avérer bénéfique à notre époque, marquée par un sens croissant de la realpolitik et la nécessite de trouver des solutions aux nombreux problèmes qui se posent.

Enfin, on peut y ajouter que le déclin du français à l’institut de Heidelberg suit une tendance politique plus large. Les relations franco-allemandes traversent une période difficile (prolongée). Comme l’ont relaté plusieurs médias français, le vice-chancelier Robert Habeck a déclaré en Septembre 2023 lors de la conférence annuelle des ambassadeurs allemands : « Nous [les Allemands et les Français] ne sommes d’accord sur rien. » Sauf, semble-t-il, en ce qui concerne une certaine distance linguistique. Le gouvernement allemand a décidé de fermer plusieurs instituts Goethe en France, malgré les dispositions du traité d’Aix-la-Chapelle de 2019, dans lesquelles les deux pays s’engagent à entretenir et renforcer l’apprentissage de la langue de l’autre. Malgré le nombre impressionnant d’étudiants ayant suivis un cursus académique binational proposé par l’Université franco-allemande (UFA) – pour la seule année 2022, plus de 1400 étudiants ont suivi les cursus franco-allemands de l’UFA dans le domaine du droit – , grâce à des programmes d’échanges comme Erasmus ou des arrangements de cotutelle, il semble y avoir (à haut niveau politique) un repli (linguistique) qui n’est pas sans conséquence pour le monde de la recherche.

Défense du français dans un contexte (académique) multilingue

Pour conclure, il ne s’agit nullement dans cette contribution de faire preuve de nostalgie, c’est-à-dire de défendre un retour à l’époque où le français était la langue de la diplomatie internationale et du droit international, ni de militer pour un duopole franco-anglais dans les relations internationales démodé. Par ces quelques lignes, je souhaite attirer l’attention des lecteurs sur la question de la diversité linguistique dans le travail universitaire, qui permet également une certaine diversité intellectuelle et conceptuelle. La prédominance de l’anglais dans les études et la pratique du droit international et européen a certes des avantages, car elle facilite (a priori) les échanges et l’accès au savoir. Mais elle a aussi des inconvénients : elle donne l’illusion d’un monde beaucoup plus unifié et inclusif qu’il ne l’est en réalité.

La dominance de l’anglais comme langue scientifique vient, en effet, avec d’importants biais analytiques, conceptuels et autres, comme l’explique Odile Ammann si aisément (dans un texte rédigé en anglais). Si nous voulons éviter un appauvrissement du débat juridique (académique) et, en revanche, maintenir une certaine richesse dans la pensée et la pratique juridiques, il est important de cultiver également une certaine diversité linguistique – sur un plan individuel et institutionnel. Compte tenu de son importance historique et actuelle – le français est la cinquième langue la plus parlée au monde après l’anglais, le mandarin, l’hindi et l’espagnol – il semble opportun que le français fasse partie de cette diversité. Pour moi en tout cas, ma patrie est le multilinguisme et le français en est incontestablement un élément important.

***

A comprehensive version of this article will be published in RuZ – Recht und Zugang

[1] L’auteure remercie chaleureusement Rocío Bargon Sánchez et surtout Chiara Miskowiec pour l’excellent soutien de recherche qu’elles lui ont apporté lors de la rédaction de cet article. Un grand merci également à Anne-Marie Thévenot-Werner pour ses commentaires très constructifs sur une version antérieure de ce texte.

[2] Photo : MPIL.

[3] Photo : MPIL.

|

Suggested Citation:

Carolyn Moser, Ma patrie, c’est le multilinguisme. Une réflexion sur l’utilisation du français dans l’étude et la pratique du droit (à l’institut Max Planck de droit international public de Heidelberg et au-delà), MPIL100.de, DOI: 10.17176/20240405-094941-0 |

|

|

Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED |

A Reflection on the Use of French in the Study and Practice of Law at the Max Planck Institute for International Law in Heidelberg and Beyond

Language is the cornerstone of all legal thought and practice.[1] In fact, it is the most important tool of lawyers, enabling them to develop ideas, present arguments and, more generally, to (re-) shape the legal framework. In other words, a lawyer’s competence is also measured by his or her command of the language. The importance of this linguistic proficiency lies in the ambiguity of (international) legal rules, as Guy de Lacharrière, former French judge at the ICJ, reminds us in his classic work “La politique juridique extérieure”, published in 1983.

Language – (far) more than another tool in the box

However, it would be simplistic to think of language as a mere tool. It is much more than that. Language impregnates our identity and provides a socio-cultural frame of reference that goes beyond its nominative nature. As Albert Camus said: “I have a homeland: the French language.”[2] Language is therefore an important vector of identity and culture, including in the legal context. Given this characteristic of identity and culture, the choice of one language over another has a significant impact on legal thought and practice.

When reading the same judgment in French and English, for instance, one quickly realises that the respective texts not only diverge linguistically, but also convey a different legal culture, sometimes even a different conception of law. Consider, for example, the Les Verts judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Communities (ECJ) of 1986. The French version of the decision refers to a “communauté de droit” (lit. legal community) (later transformed into a “Union de droit” (lit. legal union)), while the English version refers to a “Community [Union] based on the rule of law”. We all know that the Etat de droit concept (adapted by the Court to suit the European polity, i.e. the community and then the Union), which is dear to civil law systems, on the one hand, and the concept of the rule of law used by common law systems, on the other hand, differ in many respects. To think that languages (of law) are simply interchangeable means to fall back on the myth of linguistic equivalence, as Jacqueline Mowbray skilfully demonstrates. Consequently, the use of a particular language can open up to its user not only a lexical field, but also and above all a conceptual and intellectual dimension, which may even have a legal-political dimension.

For historical reasons, French enjoys a privileged status in international and European Union (EU) law. Today, this is reflected in the use of the French language as one or, in some cases, the only working language in major international judicial institutions (in alphabetical order: CJEU, ECHR, ICC, ICJ, ICTR, ICTY). The linguistic dimension of legal proceedings also raises questions of linguistic justice. What is more, French is the working language of many international institutions, including the United Nations Secretariat, as well as academic entities such as the Institut de droit international (Institute of International Law). While some may consider this linguistic privilege to be obsolete, the fact remains that it persists and permeates international and EU law. Indeed, the working language is closely linked to the language of reasoning, which means that reasoning takes place within a given legal framework (in this case, French). And without any aspiration to glorify French law, it is undeniable that it has left significant traces in many other legal systems in Europe and beyond, notably through the Napoleonic Code. It is therefore an asset for any “internationalist”, “Europeanist” or “comparatist” to be able to speak, read and write French for many reasons.

The decline of French (law) at the Heidelberg Institute

In the 1950s and 1960s, French was still one of the main foreign languages spoken at the institute. Two brochures presenting the institute and its work bear witness to this.

Despite this (relative) importance of the French language for the practice of international and European law, French and the study of francophone legal systems are scarce at the Max Planck Institute for International Law (MPIL) in Heidelberg.

To arrive at this conclusion, I plunged – with the support of my brave (student) assistant – into the Institute’s very extensive archives covering the last 100 years. We studied inter alia the protocols of the Monday Meeting (Referentenbesprechung), searched journal and library registers for publications by Institute researchers in French or on French-speaking law, deciphered the handwriting of Victor Bruns in his French-language correspondence with his peers, unpacked staples of legal opinions, collected testimonials from (former) Institute researchers, and turned over numerous pages of various activity reports. This exploration of the archives is by no means exhaustive (and doubtless not free from statistical error), but it does provide some interesting insights.

Good old days? Hermann Mosler and Suzanne Bastid, the first female law professor in France, at the “Judicial Settlement” conference in Heidelberg in 1972.[3]

Apart from a few conferences linking members of the Institute to francophone scholars, the points of contact with the francophone legal community remain sporadic, even if the institutional framework is there, such as the Franco-German academic partnership HeiParisMax, set up in 2015. Much more frequent are, indeed, scholarly exchanges and collaborations with Spanish-, Italian- and of course English-speaking researchers and institutions.

It should also be noted that very few French-speaking scholars come to pursue or deepen their research at the Institute, which also explains the low activity of the Francophone Forum with an average of one or two presentations per year: the unofficial statistics of the Institute’s international officer Mrs Stadler show that, on an annual average, only four researchers, whose working language is French, use the reading room of the Institute or work at the MPIL as guests, which is five times fewer than in the 1990s, according to the activity reports (Tätigkeitsberichte) of that time. This also contrasts significantly with the dozens of Spanish-speaking and hundreds of English-speaking scholars pursuing their research at the Institute these days. It should be borne in mind, however, that in the past, two French-speaking members have been part of the Scientific Advisory Board (Fachbeirat): Pierre Pescatore, Judge at the CJEC, in the 1970s, and Evelyne Lagrange, Professor at the Sorbonne university, in the 2010s. (The latter is still an external scientific member of the Institute today.)

Likewise, France and its legal order, as well as francophone legal systems, have (become) rather rare as objects of study at the Heidelberg Institute. This is evidenced by the low frequency of presentations on French legal news within the framework of the Monday Meeting (Montagsrunde, formerly called Referentenbesprechung), which are currently limited to a maximum of one or two annual presentations (see table 1 below). This means that the legal developments in francophone legal systems, including France, Belgium, parts of Switzerland and Canada as well as – importantly – French-speaking Africa (covering the Maghreb and big parts of sub-Saharan Africa), have virtually no resonance in the Institute, even though there are enough topics to cover. Hence, the successive coups d’Etat in the Sahel region, for example, go largely unnoticed (or at least without academic follow-up) at the Institute.

| Year |

Number of presentations on matters of French law |

| 2023 |

2 (cases before the ECHR against France) |

| 2022 |

0 |

| 2021 |

1 (case before the ICJ involving France) |

| 2020 |

2 |

| 2019 |

2 (including 1 case before the CJEU against France) |

| 2018 |

2 (including 1 case before the ICJ involving France) |

| 2017 |

1 |

| 2016 |

2 |

| 2015 |

1 |

| 2014 |

1 (case before the CJEU against France) |

| 2013 |

2 |

| 2012 |

1 |

| 2011 |

0 |

| 2010 |

2 |

| 2009 |

1 (case before the CJEU against France) |

| 2008 |

5 (including 1 case before the ICJ against France and 1 case before the ECHR against France) |

| 2007 |

6 (including 1 case before the CJEU against France) |

| 2006 |

7 |

| 2005 |

5 (including 1 case before the ECHR against France and 1 case before the CJEU against France) |

| 2004 |

2 |

| 2003 |

3 (including 1 case before the CJEU against France) |

Table 1. Presentations delivered during the Monday Meeting on subjects of French law (in the broadest sense)

An exception to the invisibility of French and francophone law and current legal events is the contribution of French-speaking colleagues to comparative collective works, particularly in the context of the Ius Publicum Europeum project. However, these publications are written in either English or German. On the other hand, it has become very rare for MPIL researchers to publish in French (nowadays). The situation was different twenty or thirty years ago. Until the late 1980s, for example, the Institute regularly published trilingual collections (German, French, English) in the Schwarze Reihe. In fact, between 2002 and 2021, the Schwarze Reihe had no publications in French. Today, on average, 1.5 publications (all types of output – article, chapter, blog – taken together) is published in French per year by one of the Institute’s roughly 50 researchers. Since 2000, only one French-language article has been published in the Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (ZaöRV) on a question of Mauritanian law. The picture is brighter for the Journal of the History of International Law/ Revue d’histoire du droit international, where the latest contributions in French date back to 2020. Articles in German (or English) on French or francophone law published in these two journals can be counted on the fingers of two (small) hands. There have been a few reviews of monographs and collective works published in French, though. All things considered, French is far from being a research language at the Institute, let alone a working language (even at the tertiary level, after German and English).

Analysis of language practices and skills

Telegram from Paul Lachenal, President of the German-Polish Court of Arbitration, to German arbitrator Viktor Bruns. The court’s correspondence and work were conducted exclusively in French.

This linguistic reality contrasts sharply with the situation in the past. In the inter-war period, for example, Director Viktor Bruns dealt exclusively in French with cases related to the German-Polish Mixed Arbitral Tribunal, which was established under the provisions of the Versailles Peace Treaty and of which he was a member. What is more, Directors Hermann Mosler – as a judge at the ECHR (1959-80) and the ICJ (1976-85) – and Jochen Frowein – as a member of the European Commission of Human Rights in Strasbourg (1973-93) – carried out a large part of their (para-) judicial work in French.

It should also be noted that the Institute’s researchers have generally written reports and opinions on French law. Leaving aside all the opinions on the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and on the pursuit of European integration, on matters concerning the law of war, on the Council of Europe which (also) had a link with France, and all opinions of comparative law, there are 13 opinions from 1949 to 1998 which deal exclusively with questions of French law, two thirds of which were drafted in the 1950s (see table 2 below). However, those expert reports seem to have been discontinued since 1998, when Jochen Frowein and Matthias Hartwig produced their report on the legal situation of the cultural goods seized or expropriated by France.

| Year |

Title [with English translation] |

Authors |

| 1998 |

Rechtslage der von Frankreich beschlagnahmten bzw. enteigneten Kulturgüter [Legal situation of cultural goods seized or expropriated by France] |

Jochen A. Frowein and Matthias Hartwig |

| 1997 |

Vereinbarkeit des Gesetzes über die Rechtsstellung der Banque de France mit dem EG-Vertrag [Compatibility of the Law on the Statute of the Banque de France with the EC Treaty] |

Jochen A. Frowein, Peter Rädler, Georg Ress and Rüdiger Wolfrum |

| 1981 |

Rücknahme und Widerruf von begünstigenden Verwaltungsakten in Frankreich, Großbritannien, Italien und den Niederlanden [Withdrawal and revocation of favourable administrative acts in France, Great Britain, Italy and the Netherlands] |

Karin Oellers-Frahm, Rudolf Dolzer, Rolf Kühner, Hans-Heinrich Lindemann and Werner Meng |

| 1962 |

Entschädigungssache des Herrn Jaques Sztern, Paris / Land Nordrhein-Westfalen [Claim for compensation from Mr Jaques Sztern, Paris / Land of North Rhine-Westphalia] |

Fritz Münch |

| 1957 |

Communauté de Navigation Française Rhénane – Land Rheinland-Pfalz betr. Staatshaftung [Communauté de Navigation Française Rhénane – Land of Rhineland-Palatinate with regard to State liability]. |

Günther Jaenicke |

| 1956 |

Welches Erbrecht ist beim Tode eines aus rassischen Gründen emigrierten früheren deutschen Staatsangehörigen, der in Frankreich lebte und in Auschwitz ums Leben kam, von dem deutschen Nachlaßgericht für die Erteilung eines gegenständlich beschränkten Erbscheines anzuwenden? [What law of succession applies to the death of a former German national who emigrated for racial reasons, who lived in France and died in Auschwitz, for the purpose of issuing a certificate of inheritance?] |

Günther Jaenicke |

| 1956 |

Der Rentenanspruch des unehelichen Kindes eines in französischen Diensten gefallenen deutschen Fremdenlegionärs gegen den französischen Staat [The pension entitlement of the illegitimate child of a German legionnaire who died in the service of France against the French state] |

Günther Jaenicke |

| 1955 |

Zulässigkeit des Elsässischen Rheinseitenkanals [Lawfulness of the Lateral Rhine Canal in Alsace] |

Günther Jaenicke |

| 1954 |

Die völkerrechtliche und staatsrechtliche Stellung des Saargebietes [Saarland’s status in international and public law] |

Carl Bilfinger, Günther Jaenicke and Karl Doehring |

| 1953 |

Die völkerrechtliche und staatsrechtliche Stellung des Saargebietes [Saarland’s status in international and public law] |

Günther Jaenicke and Karl Doehring |

| 1952 |

Die Stellung des Saargebietes als assoziiertes Mitglied des Europarates [Saarland’s position as an associate member of the Council of Europe] |

Günther Jaenicke |

| 1951 |

Bürger und Wehrmacht in Frankreich [Citizens and the Wehrmacht in France] |

Hans Ballreich |

| 1951 |

Die rechtliche Stellung der politischen Parteien in Frankreich [The legal status of political parties in France] |

Günther Jaenicke |

Table 2. Opinions on questions of French law drafted by researchers of the institute

How then can we explain this lack of interest in the French language at the Heidelberg Institute, or even in francophone law today? The reason for this development is undoubtedly multifactorial. The most logical explanation would be the decline in the language skills of the Institute’s researchers. As a matter of fact, many staff members of the Institute were francophone (or even francophile) in its founding period and after the Second World War. This applied to the researchers, but also to their multilingual secretaries. So, where do we stand today? The hypothesis of a decline in language skills does not hold water: a linguistic inventory of the Institute’s scientific staff shows that the vast majority of researchers employed by the Institute have completed a period of their studies in France (or the francophone part of Switzerland or Canada), and sometimes even hold a degree from a French-speaking university. They are therefore perfectly qualified to follow legal developments in the French-speaking world. The decline in the use of French at the Institute can thus hardly be explained by a lack of language skills. Moreover, the current directors – Anne Peters and Armin von Bogdandy – also have an excellent command of French, which they regularly use at French-speaking events.

The Anglophone hegemony

The French language is still used in the library’s classification system, introduced in 1924. The country codes for journals are still French: American journals are listed under EU (États Unis).

Another hypothesis might be that the moderate use of French and the limited study of francophone law at the Institute simply reflect the broader political and legal context and, therefore, the declining importance of French in international legal practice. French plays a prominent role in international law because, to put it simply, France was a major (colonial) power at the time when the current international legal system took shape. As a result, until the 20th century, international diplomacy used to be conducted in French, and many international legal instruments were drafted in French. This is evidenced by the collections of treaties and jurisprudence published or edited by staff members of the Institute. Among these are the Nouveau recueil général de traités et autres actes relatifs aux rapports de droit international (Recueil Martens) (published by the Institute between 1925 and 1969) and the Fontes iuris gentium (published by the Institute between 1931 and 1990), which switched entirely into English in 1986 (under the name World Court Digest).

Although France retains a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council and remains a pillar of the European project, it has for quite some time now ceased to be a great power. This has had an undeniable impact on the use of the French language, which is in decline, not to say collapse, in favour of English, which has become the lingua franca of international relations since the Second World War. For instance, the Treaty of Aachen – signed by France and Germany in 2019 – was first written and negotiated in English by diplomats of both countries, and then translated into French and German. The world of diplomacy is changing, and so are language habits and preferences.

This brings us to a third factor that may help to explain the decline of French at the MPIL in Heidelberg: the Anglophonisation of the research world, including in the field of law. For internationalists, Europeanists or comparative public/ constitutional lawyers, English is now the first language of interaction and, above all, the prevailing, if not predominant, language of publication. Just take a look at the list of the most cited academic journals in the field of international law, all of which are published in English. Despite the fact that, thanks to digital tools, we can now much more easily consult sources in several languages and translate the writings of our colleagues, we have noticed over the last twenty years that academics are mainly and increasingly referring to English-language sources. This applies to international law, as Allain Pellet had already deplored in 1988 in a letter to the editors of the American Journal of International Law (AJIL), as well as to European law as Daniel Thym’s insightful analysis of 2016 shows. This linguistic bias towards English is, moreover, particularly pronounced among American authors who, in the words of Christian Tomuschat, “remain deliberately within the cage of the Anglophone literature without ever looking beyond their own home-grown source.” Although tools such as DeepL or ChatGTP allow us to approach foreign-language sources more easily, their use can complement basic linguistic expertise, but it cannot replace it. Moreover, digital tools often favour English because of the algorithms they employ – but that’s yet another debate.

French has thus been replaced not only as the language of international diplomacy and therefore of the practice of international law, but also as a research language in international (and European) law. A particularly radical and significant change in this respect was the disappearance of French as the language of publication of the European Journal of International Law in 1998, when the journal came under the management of the British publisher Oxford University Press, only ten years after its launch as a bilingual (French/ English) journal by polyglot academics.

In any case, the situation at the Heidelberg Institute is not an exception, but part of a general linguistic trend. In other words, we are witnessing the decline of French as a result of the globalisation and diversification of the research world. Following this logic, the question is whether the last bastions of French – in particular the Institut de droit international – will be able to impose its francophone language policy over time, especially given that some discussions at said Institut are already held in English, as Anne Peters, a member of this institution since 2021, told me.

Aggravating factors: academic and political barriers

German and French researchers side by side. Karl-Josef Partsch (left) and Jean-Maurice Verdier (right) in 1978 at the colloquium “Koalitionsfreiheit des Arbeitnehmers”[4]

The peculiarities of the French academic landscape in (international) law, characterised by a pronounced formalism and very specific methods (just to mention the “deux parties / deux sous-parties” outline), do not necessarily make legal research emanating from the French tradition easily accessible. Yet, as Andrea Hamann has shown with great analytical finesse, the French tradition of international law (and to some extent European law) is pragmatic. This pragmatism is inspiring, even refreshing for some, and could prove advantageous in our time, marked by a growing sense of realpolitik and the need to find solutions to the many emerging problems.

Finally, we can also observe that the decline of French at the Heidelberg Institute follows a broader political trend. The Franco-German relationship is going through a (prolonged) difficult period. As reported by several French media, Vice-Chancellor Robert Habeck remarked in September 2023 at the annual conference of German ambassadors: “We [the Germans and the French] do not agree on anything.” Except, it seems, on a certain linguistic distance. The German government has decided to close several Goethe Institutes in France, despite the provisions of the 2019 Treaty of Aachen, which stipulates that the two countries are committed to maintaining and strengthening the learning of each other’s languages. Despite the impressive number of students who have completed a binational academic programme offered by the French-German University (UFA) – in 2022 alone, more than 1,400 students followed Franco-German law courses at the UFA – thanks to exchange programmes such as Erasmus or cotutelle agreements, there seems to be a (linguistic) regression (at a high political level), which is not without consequences for the research world.

Advocating French in a multilingual (academic) context

In conclusion, this contribution is by no means intended to be nostalgic, i.e. to urge a return to the days when French was the language of international diplomacy and international law, or to advocate an outdated Franco-English duopoly in international relations. With these few lines, I would like to draw the readers’ attention to the need for linguistic diversity in academic work, which also allows for a certain intellectual and conceptual diversity. The predominance of English in the research and practice of international and European law certainly has its advantages, making (a priori) exchange and access to knowledge easier. But it also has its downsides: it gives the illusion of a world that is much more unified and inclusive than it actually is.

Indeed, as Odile Ammann explains so delicately, the dominance of English as the language of academia is accompanied by significant analytical, conceptual and other biases. If we want to avoid an impoverishment of the (academic) legal debate and, on the other hand, maintain a certain richness in legal thought and practice, it is important to cultivate linguistic diversity – at both the individual and the institutional level. It seems appropriate that French should be part of this diversity, given its historical and contemporary importance – it is the fifth most spoken language in the world after English, Mandarin, Hindi and Spanish. For me in any case, my homeland is multilingualism, and French is undoubtedly an important part of that.

***

A comprehensive version of this article will be published in RuZ – Recht und Zugang

[1] The author would like to warmly thank Rocío Bargon Sánchez and especially Chiara Miskowiec for their excellent research assistance during the drafting of this article. The original French text was translated into English with the help of Rocío Bargon Sánchez. Many thanks also to Anne-Marie Thévenot-Werner for her highly constructive comments on an earlier version of this text.

[2] In French, Camus’ statement reads as follows: “J’ai une partie: la langue française.”

[3] Photo: MPIL.

[4] Photo: MPIL.

|

Suggested Citation:

Carolyn Moser, Multilingualism as a Homeland. A Reflection on the Use of French in the Study and Practice of Law at the Max Planck Institute for International Law in Heidelberg and Beyond, MPIL100.de, DOI: 10.17176/20240405-095049-0 |

|

|

Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED |