When the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Foreign Public Law and International Law began to operate in January 1925 with a smaller advance team, Marguerite Wolff was a driving force in getting the Institute up and running. According to the diary of Marie Bruns, wife of the Institute’s founding director Viktor Bruns, their friend Marguerite Wolff was not only a member of the academic staff but also what she called the Institute’s housewife.[1] Before we further explore her contribution to this Institute, a few biographical facts should be mentioned.

Family and personal background

Marguerite Wolff, nee Jolowicz, was born in London on 10 December 1883, as a dual British-German citizen, the latter through her father Hermann Jolowicz (1849-1934), a wealthy silk merchant who was born in (then Prussian) Pleschen (Pleszew) and learned the trade in Lyon. Her mother was Marie Litthauer, born 1864 in (then also Prussian) Neutomysl (Nowy Tomyśl). Marguerite had two brothers, Paul (born 1885) and Herbert Felix (born 1890), who would later become Regius Professor of Civil Law at the University of Oxford.[2] Unusually for women at the time, but in line with her liberal bourgeois upbringing, Marguerite Jolowicz obtained a Master of Arts in English from Cambridge University, apparently with a “first”, and as student of Newnham College.[3] In 1906, she married the legal scholar Martin Wolff (1872-1953) and moved to Berlin, then to Marburg (1914), Bonn (1918), and back to Berlin (1921). Marguerite and Martin Wolff had two children: Konrad (1907-1989), who later became a famous pianist, and Victor (1911-1944), who qualified as a barrister and served in the Royal Air Force.[4]

“Housewife”, Assistant, Fellow? Marguerite Wolff at the Institute

Marguerite Wolff, as photographed by Ilse Bing (her daughter-in-law), 1947[5]

Marguerite Wolff worked at the Institute between 1 January 1925 and 1 May 1933 when her employment contract was terminated in the wake of national-socialist legislation aimed at removing all Germans of Jewish origin from public service or related employment. More will be said on this below.

Next to the short entry in the diary of Marie Bruns, we have one other contemporaneous and three non‑contemporaneous first-hand descriptions of her activities at the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Foreign Public Law, with the later descriptions dating from 1951/1952 and relating to compensation claims pursued by Marguerite Wolff.

In a very short self-description, Marguerite Wolff stated in 1951 that she had been employed as “Referentin [senior research fellow in modern MPIL English terminology] for the English and American notions of public international law” and that her employment “ended through termination by Professor Bruns on the basis of racial legislation”.[6] A glowing Dienstzeugnis (reference provided by employer on leaving service) written by Viktor Bruns and dated 19 December 1933 confirms the dates of her employment, initially as “wissenschaftliche Assistentin”, then “Referentin”, and specifies her academic area of work as “public international law with particular emphasis on England and the United States”, with the tasks of “observing the most recent political and legal developments which are relevant for public international law, to compile reports for the archive and the editors of the [Institute’s] journal, and to work academically on smaller and larger specific questions”. Moreover, Bruns notes her outstanding contribution to the editing of the Institute’s journal, her compiling of texts in the English language, providing English-German and German-English translations, and giving English legal terminology courses for other members of the Institute. Bruns praised her as completely bilingual and in full command of legal, political, and economic terminology.[7] The reference contains only a short description of her initial managerial role: “She was instructed with organizational tasks during the set-up of the Institute.”[8]

There is also a warm personal testimonial from 1952 by Marianne Reinert, non-academic staff member of the administration of the Max Planck Society and its predecessor, the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. She states:

“The wife of Prof. Wolff, Marguerite Wolff, an exceptionally intelligent and amiable woman, was one of those personalities who, together with Prof. Bruns, a close friend of hers, built up the Institute for Public International Law in the year 1925. Together with myself, working in the office of the president of our general administration located in the palace [Berliner Schloss], she compiled the starting stock of the library, and then worked as Abteilungsleiterin [head of division] in the Institute. In 1933, Professor Bruns advised her not to return from a holiday in London, where her brother worked as a respected banker, on account her being Volljüdin [of full Jewish descent]. She therefore stopped being a member of the Institute.”[9]

A lawyer without formal training?

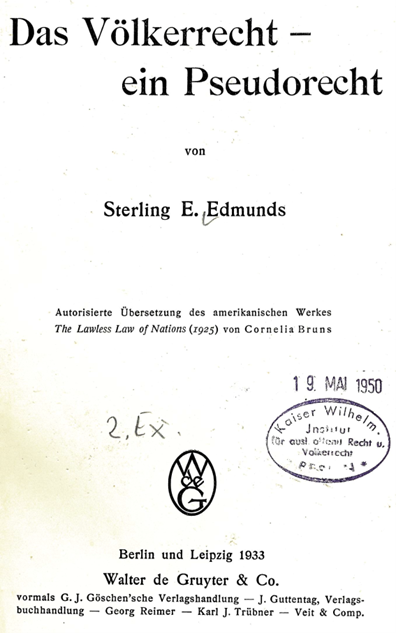

Finally, there is a somewhat problematic testimonial by the former librarian of the Institute, Curt Blass. He begins by giving credit: “Mrs M. Wolff had an important share in the organisational set-up of the Institute in the first years after it had been founded. She was at the time the main staff member for the Director, both academically, and as his secretary.”[10] But he then goes on to describe how after the initial phase her tasks became more and more limited, her lack of legal education a problem, and that no one was surprised when “Professor Bruns announced that Mrs. Wolff had decided to leave the Institute and return to her home country England, to where her husband had already relocated.” That last allegation was certainly incorrect: Martin Wolff only moved to England in 1938.[11] Moreover, the allegation of shortcomings can hardly be squared with Marguerite Wolff’s book on UK press law which the Institute published in 1928.[12] This is a masterly exercise in comparative law, explaining peculiarities of English law to an audience of lawyers trained in the German legal system, which gives the readers no clue that the author had formal legal training in neither English nor German law. It appears much more likely that Viktor Bruns’ reference correctly described the many talents and contributions which the Institute lost when Marguerite Wolff’s contract was terminated.

As the Institute’s own archive reveals, Blass tailored his testimonial to the expectations which Hans Ballreich had formulated on behalf of the Institute. Ballreich had specifically asked Blass to consider the alternative narrative that Marguerite Wolff had decided of her own accord to move to London with her family, lamenting the danger of the Max Planck Society being burdened with very considerable, and in many cases unmerited, compensation claims.[13] Blass expresses his disquiet about this request not in his testimonial, but in a cover letter to Ballreich which was not forwarded to the Max Planck Society. In this cover letter, Blass explains that this request is “a rather delicate task. I have attempted to solve this as well as I can. If you believe that the attached notes could be of use to the Society, please pass them on.”[14] It should be added that there is nothing in the compensation claim file which would suggest that the Max Planck Society had put any pressure on Ballreich. The German Federal Ministries involved had, quite to the contrary, all along been pushing for a favourable treatment of Marguerite Wolff’s compensation claims.[15]

Few other sources appear to exist on the role which Marguerite Wolff played at the Institute. The Institute’s own files perished in a fire which ravaged the Berlin Palace in 1945, and only occasional and fleeting mentions of Marguerite Wolff in other contemporaneous sources have so far emerged.

Those who have previously written about Marguerite Wolff have come to different conclusions about her role at the Institute, and the circumstances surrounding her leaving the Institute. She has been called “unofficial co-director”, “head of division”, or “unofficial head of division” at the Institute. [16] The evidential basis for these attributions remains unclear. Unlike some other Kaiser Wilhelm or Max Planck Institutes, this institute did not have any divisions (Abteilungen)[17] and still does not today. And while the strongest support for the significance of Marguerite Wolff’s role in the Institute’s initial phase is found in the (otherwise problematic) testimonial of Blass, one could easily question whether that would make her an unofficial co-director. This is not how KWI directors were understood to operate under the so-called Harnack Principle, exercising full control over their institute’s research agenda and the hiring of academic staff. It might be more appropriate to translate the somewhat antiquated notion of Marguerite Wolff as the Institute’s “housewife” into 21st century language as staff member with a leading managerial function, in charge of the practical aspects of building up the new institute from scratch.

But little will eventually hang on this terminological question. If we assume instead that Marguerite Wolff and Viktor Bruns correctly described her as Referentin or Senior Research Fellow, this will do nothing to belittle the outstanding achievements of this extraordinary woman. It means that she was treated, as appropriate, on par with fully trained male colleagues at the Institute who shared the same job title, including influential scholars such as Hermann Heller and Gerhard Leibholz.[18]

It is safe to assume that Marguerite Wolff leaving the Institute was triggered by the racial persecution of Jews and the enactment of legislation in April 1933 which would exclude most (and eventually all) persons of Jewish descent from holding any public office. At the same time, the story could be more complex than her being dismissed in April 1933 in immediate application of the infamous Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums [Law to restore the professional civil service]. In April, that applied only to civil servants, then from 4 May 1933 to employees of public law bodies. The earliest dismissal date for such employees would have been 30 June 1933,[19] but this would still not apply to any employees of the Institute, as the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft was organised as a private association. Given that the Brunses were close friends with the Wolffs and not known for national-socialist sympathies, it appears unlikely that Marguerite Wolff was unilaterally dismissed with effect of 1 May 1933 against her express wishes. Conversely, there is nothing to suggest that Marguerite Wolff handed in her own termination notice, which would probably likewise have been too short. While Bruns’ reference remains silent on how and why her employment was terminated, the most likely explanation appears to be that Wolff and Bruns agreed that Bruns would terminate the contract in correct anticipation of further persecution and any lack of medium-term perspective, and that the unduly short notice period was also consensual. On the other hand, the suggestion that this would allow her to not return from a vacation in England is misleading. It was not until 1935 that Marguerite Wolff would move to London to pave the way for her husband’s eventual move to Oxford and London in 1938.[20]

This is not the occasion to explore in detail Marguerite Wolff’s professional and personal life after she left the Institute. Suffice it to say that she worked as news editor for the BBC and as translator at the Nuremberg Trials, supervising the translations of the trial proceedings,[21] that she would eventually receive some compensation for her dismissal, and that she died in 1964.[22] While racial persecution cut her academic career short, she nevertheless continued to contribute to the world of learning as an exceptionally gifted translator and editor of legal texts. She helped to make the work of Martin Wolff’s faculty colleague and fellow émigré scholar Fritz Schultz known to the anglophone world by translating his “Principles of Roman Law” to considerable acclaim. As one reviewer noted: “The translator is to be congratulated on her success in a difficult task. Refractory Law-German has been reduced to clear, readable English”.[23] Moreover, her linguistic contribution to Martin Wolff’s famous textbook on Private International Law was praised by one reviewer as follows: “The excellence of the English is due principally to Mrs. Wolff, whose skill in rendering the author’s thoughts into precise, technical but eminently readable language is a triumphant success”.[24]

[1] Excerpt from Marie Bruns’ marriage diary „Das Institut für Völkerrecht und ausländisches Staatsrecht“, private archive of Rainer Noltenius, Bremen (Germany), transcription by Philipp Glahé, translation by the author, 2.

[2] Interview with Professor J. Anthony Jolowicz (1926-2012), nephew of Marguerite Wolff, Cambridge, 6 February 2002; letter by J. Anthony Jolowicz to the author, dated 11 August 2002; Thomas Hansen, Martin Wolff (1872-1953), 1st ed., Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 2009, 24, citing to a letter by J. Anthony Jolowicz, dated 29 August 2005; Some sources state, probably erroneously, that she re-acquired British citizenship: Herbert A. Strauss/Werner Röder/K.G. Saur (gen. eds.), International Biographical Dictionary of Central European Emigrés 1933-1945, Vol. II Pt.2: The Arts, Sciences, and Literature, Munich: De Gruyter 1983, 1261, “Wolff, Konrad Martin”.

[3] Marion Röwekamp, Juristinnen – Lexikon zu Leben und Werk, 1st ed., Baden-Baden: Nomos 2005, 436-438, 436; While her MA in English from Cambridge University is assured from other sources, this is plausible but less certain for Newnham as her college and the “first” mark, as Röwekamp’s contribution contains several inaccuracies: Marguerite was the oldest (not the second) child; her brother Herbert Felix became Regius Professor in Oxford (not Cambridge); she moved to England in 1935 (not 1933); her son Victor, by contrast, moved to London in 1933 (not 1935) and died in 1944 (not 1942).

[4] Hansen (fn. 2), 24-25, 42-54, 102; Gerhard Dannemann, Martin Wolff (1872-1953), in: Jack Beatson/Reinhard Zimmermann (eds.), Jurist Uprooted, OUP: Oxford 2003, 44-45, 441-461; On Konrad Wolff: see Ruth Gillen (ed.), The Writings and Letters of Konrad Wolff, Greenwood Press: Westport, Connecticut 2000.

[5] Photo: MPIL Archive.

[6] Letter by Marguerite Wolff to “the Director” of the Institute, dated 8 September 1951, APMG, I-1A-3170. Translated from the German original by the author.

[7] Dienstzeugnis for Marguerite Wolff by Victor Bruns, dated 19 December 1933, AMPG, I-1A-3170.

[8] AMPG (fn. 7).

[9] Letter by M[ariannne] Reinert to Mr. Pfuhl, Max Planck Society, dated 9 October 1951, APMG, I-1A-3170: Her short report is based on her own and recollections of some other staff; the 18 year time gap and the fact that she worked for the KWI general administration may explain some of the inaccuracies.

[10] Testimonial by Curt Blass, dated 19 January 1952, AMPG, I-1A-3170; It is doubtful whether Marguerite Wolff ever undertook core secretarial tasks for Viktor Bruns, as Marie Bruns (fn. 1) mentions that the Institute already employed five secretaries when it began to operate.

[11] Dannemann (fn. 4), 449.

[12] Viktor Bruns/Kurt Hentzschel (eds.), Die Preßgesetze des Erdballs, Bd. II: Marguerite Wolff, Das Preßrecht Großbritanniens, Berlin: Verlag Georg Stilke 1928.

[13] Letter by Hans Ballreich to Dr. Curt Blass in Zürich, dated (incorrectly) 14 January 1950 [in fact: 1952], Archive of the MPIL, staff file of Marguerite Wolff, translation by the author.

[14] Letter by Curt Blass to Hans Ballreich, dated 19 January 1952, Archive of the MPIL, staff file of Marguerite Wolff, translation by the author.

[15] See also: Michael Schüring, Minveras verstoßene Kinder. Vertriebene Wissenschaftler und die Vergangenheitspolitik der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Göttingen: Wallstein 2006, 198 f.: critical of the fact that ministerial support was primarily due to the eminence of her deceased husband.

[16] „Unofficial co-director“: Annette Vogt, Marguerite Wolff, in: Jewish Women’s Archive (ed.), The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, last updated 11 May 2022, online: <https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/wolff-marguerite>; Röwenkamp (fn. 3), 437 (“unofficial co-director”, at a later stage); “head of division” (Abteilungsleiterin): Schüring (fn. 15), 196, citing in note 126 incorrectly to the testimonial of Viktor Bruns (fn. 6); “inofficial head of division” (inoffizielle Abteilungsleiterin): Annette Vogt, Wissenschaftlerinnen in Kaiser-Wilhelm-Instituten A-Z, 2nd ed., Berlin: AMPG 2008, 216.

[17] Adolf von Harnack (ed.), Handbuch der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, Berlin: Verlag Reimar Hobbing 1928, 214.

[18] Von Harnack (fn. 18).

[19] § 3 Abs. 1 Zweite Durchführungsverordnung zum Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums.

[20] See Hansen (fn. 2), 102.

[21] Gillen (fn. 4), xxi.

[22] Hansen (fn. 2), 95 f.

[23] P.W. Duff, Review of Fritz Schulz, Principles of Roman Law, Classical Review 51 (1937), 238-239.

[24] John Morris, Review of Martin Wolff, Private International Law, LQR 62 (1946), 88-91, 90.

|

Suggested Citation: Gerhard Dannemann, Marguerite Wolff at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, MPIL100.de, DOI: 10.17176/20240403-102936-0 |

|

| Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED | |

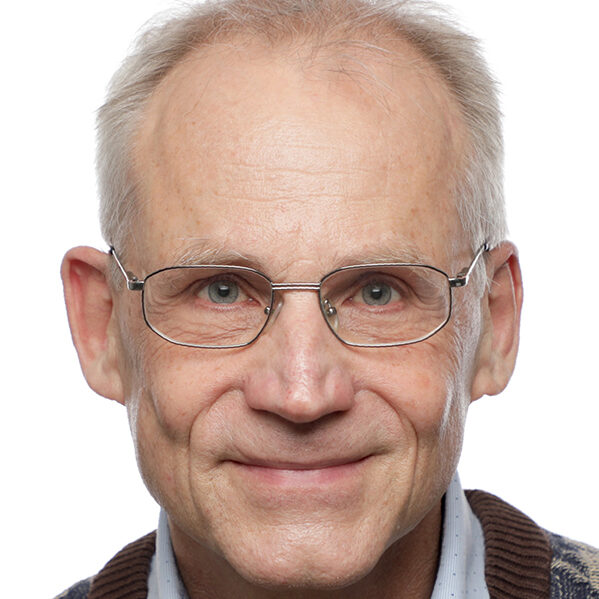

Gerhard Dannemann is Professor of English Law, British Economy and Politics at the Centre for British Studies, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of European and Comparative Law, University of Oxford. He has worked on émigré scholars Martin Wolff and F.A. Mann.