Deutsch

Als ich im Sommer 1991 aus meiner Heimat Südafrika nach Deutschland kam, gab es große Veränderungen im Land, in der Region und in der Welt. Es war die Zeit kurz nach der deutschen Wiedervereinigung, des Zusammenbruchs der ehemaligen Sowjetunion, der Invasion Kuwaits durch den Irak und des Krieges im ehemaligen Jugoslawien. Es war auch eine Zeit großer Veränderungen und Herausforderungen in Südafrika, als sich das Land auf seine ersten demokratischen Wahlen und den Übergang von der weißen Minderheitsregierung zur konstitutionellen Demokratie vorbereitete.

Es war für mich aber auch eine Zeit eigenen intellektuellen Wandels, nachdem ich an das Institut (damals noch in der Berliner Straße untergebracht) gekommen war, um für meine Doktorarbeit über die Bedeutung des deutschen Sozialstaatsprinzips für die künftige südafrikanische Verfassung zu forschen. Während in den 1980er Jahren mehrere südafrikanische Wissenschaftler am Institut tätig waren, war ich zu dieser Zeit eine der wenigen südafrikanischen Wissenschaftlerinnen, die die Gelegenheit zu einem Forschungsaufenthalt hatten. Ich war erst 23 Jahre alt und hatte gerade mein Jurastudium in Freistaat in Südafrika abgeschlossen. Für mich waren die fast zwei Jahre am Institut von Spätsommer 1991 bis zum Frühjahr 1993 prägend – und ein Quantensprung in meiner intellektuellen Entwicklung, der sich letztlich entscheidend auf meinen beruflichen Werdegang auswirkte.

Deutsche erklären die Welt? Einblicke in die Diskussions- und Wissenschaftskultur am MPIL der 1990er

Da ich von einer kleinen, regionalen juristischen Fakultät in Südafrika kam, zu einer Zeit, als das Land aufgrund der Apartheidpolitik politisch noch sehr isoliert war und der akademische Austausch und das kritische Denken dort auf viele Hindernisse stießen, ist es nicht verwunderlich, dass ich meine Heidelberger Umgebung anfangs als einschüchternd und befreiend zugleich empfand. Meine deutschen Sprachkenntnisse waren damals noch sehr begrenzt (im Wesentlichen erworben während zweier intensiver Studienmonate im Sommer 1991 am Goethe-Institut in Schwäbisch Hall) und reichten noch nicht aus, um schwierige deutsche Rechtstexte zu lesen. Auch auf dem Gebiet der Rechtsvergleichung, des Völkerrechts und des Auftretens auf der internationalen akademischen Bühne klafften große Wissens- und Erfahrungslücken. Es konnte daher einschüchternd sein, mit gut ausgebildeten und oft weit gereisten und kultivierten (damals überwiegend männlichen) wissenschaftlichen Mitarbeitenden über eine Vielzahl von rechtlichen und gesellschaftlichen Fragen zu diskutieren.

Manchmal allerdings wünschte ich mir sogar, dass diese Kollegen eher bereit wären, unvoreingenommen zuzuhören, statt sich gleich über hochkomplexe politische und juristische Zusammenhänge in fernen Ländern – mit denen sie persönlich nur wenig Erfahrung hatten – zu äußern, so belesen sie auch zu einem bestimmten Thema sein mochten. Gleichzeitig war es befreiend, sich in einem Umfeld zu befinden, in dem eine fundierte Debatte eine Selbstverständlichkeit war. Darüber hinaus waren diese Diskussionen wichtig, um zu lernen, sich zu behaupten – oft als einzige Frau in der Gruppe (zu einer Zeit, als es kaum ein Bewusstsein für die unbewussten Vorurteile gab, die mit solchen Konstellationen einhergehen) – und dazu in einer Fremdsprache. Darüber hinaus wurde das Bewusstsein dafür geschärft, wie wichtig eine solide Debatte in Verbindung mit Toleranz (einschließlich der Bereitschaft aufmerksam zuzuhören) ist, um eine nuancierte, ausgewogene und tiefgründige akademische Forschung zu fördern. Diese aus meiner Sicht unerlässliche Qualität ist zum Zeitpunkt des Verfassens dieses Beitrags leider zunehmend eine Seltenheit auch an vielen intellektuellen Elite-Institutionen geworden, unter anderem aufgrund des zerstörerischen Einflusses der sozialen Medien, die darauf abzielen, zu polarisieren und zu ‚canceln‘ und damit die Grundlagen der akademischen Freiheit und des demokratischen Diskurses zu untergraben.

Eine lebenslange Verbindung. Der bleibende Einfluss des MPIL

Wichtig war für mich damals die enge soziale Interaktion mit den wissenschaftlichen Mitarbeitenden und einem ganz allgemein sehr unterstützenden Umfeld, wozu auch die damaligen Direktoren beitrugen. Zu dieser Zeit wurde das Institut von Jochen Abr. Frowein und dem mittlerweile verstorbenen Rudolf Bernhardt geleitet. Es gab auch eine kurze Überschneidung mit Rüdiger Wolfrum vor meiner Abreise im Jahr 1993, als er die Nachfolge von Rudolf Bernhardt als Direktor des Instituts antrat. Sowohl Jochen Frowein als auch Rüdiger Wolfrum blieben sehr interessiert an meiner Karriere und unterstützten sie. Zum Beispiel hatte ich nach der Unabhängigkeit des Südsudan im Jahr 2011 die Gelegenheit, mit Rüdiger Wolfrum und seinem Team bei der Beratung zur Verfassungsreform im Südsudan und später auch Sudan zusammenzuarbeiten und dabei auch auf die Erfahrungen Südafrikas in den 1990er Jahren zurückzugreifen. Als große Ehre habe ich empfunden, dass ich im Jahr 2020 (zusammen mit Kathrin Maria Scherr) die Herausgeberschaft des Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law (UNYB) übernehmen durfte, welches im Jahre 1997 von Jochen Frowein und Rüdiger Wolfrum begründet worden war. Der Einfluss ihrer Forschung auf meine eigene Arbeit und die herausragende Rolle des Völkerrechts in der Arbeit des Instituts im Allgemeinen führten ferner dazu, dass sich mein Hauptforschungsinteresse im Laufe der neunziger Jahre vom vergleichenden Verfassungsrecht zum Völkerrecht verlagerte.

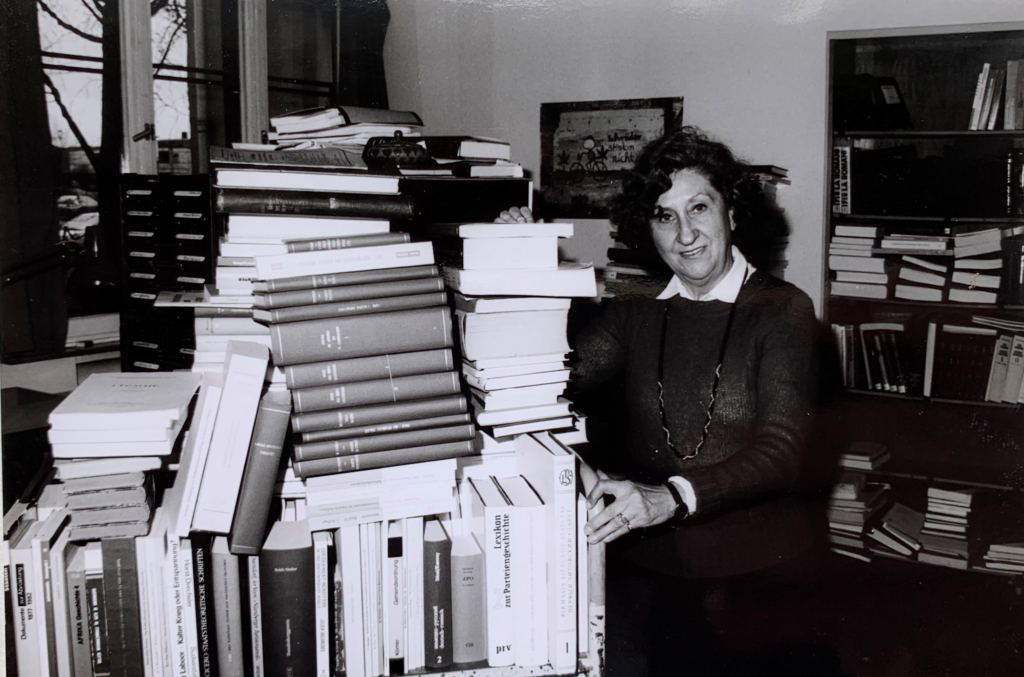

Ein weiterer einzigartiger Aspekt des Instituts war und ist der legendäre Bibliotheksbestand, sowohl in Bezug auf das vergleichende öffentliche Recht als auch auf das Völkerrecht. Wissenschaftler (sowohl junge als auch etablierte) aus ganz Europa und darüber hinaus besuchten die Bibliothek vor allem in den Sommermonaten, was zu einer sehr lebendigen Gemeinschaft von Wissenschaftlern des öffentlichen Rechts und des Völkerrechts führte, die zu dieser Zeit wahrscheinlich einzigartig in Europa war. Der sich daraus ergebende Austausch versorgte auch das akademische Personal des Instituts mit einer Fülle von Informationen, die sowohl für die eigene Forschung als auch für die Arbeit des Instituts insgesamt relevant waren. Der Wissenstransfer, der in und um die Bibliothek herum stattfand, war also eine Zweibahnstraße und von grundlegender Bedeutung zu einer Zeit, als es noch kaum digitale Ressourcen und Kommunikation gab. Für mich persönlich war es auch ein Anstoß, weitere internationale Erfahrungen zu sammeln und neue Horizonte zu erkunden. Ich hatte auch das große Glück, Matthias Herdegen, ehemaliger Referent am Institut und damals Professor an der Universität Konstanz, kennenzulernen. Wegen sein Interesse an den verfassungsrechtlichen Entwicklungen in Südafrika nahm er Kontakt zu mir auf und der Austausch entwickelte sich zu einer nachhaltigen, bis heute andauernde Zusammenarbeit.

Es fiel mir sehr schwer, Heidelberg im Frühjahr 1993 zu verlassen, aber ich hatte das große Glück, die Verbindung zum Institut und zur Stadt in den folgenden Jahren aufrechtzuerhalten, sei es durch anschließende Forschungsaufenthalte, die von der Alexander‑von‑Humboldt‑Stiftung gefördert wurden, oder durch die Teilnahme an einer Reihe von wissenschaftlichen Veranstaltungen und persönlichen Kontakten die sich bis heute gehalten haben. In den letzten Jahren hat sich meine Verbundenheit auch auf die von Rüdiger Wolfrum 2013, nach seiner Emeritierung als Direktor am Institut, gegründete Max‑Planck‑Stiftung für Internationalen Frieden und Rechtsstaatlichkeit ausgeweitet, deren Projekte zur Verfassungsreform global Anerkennung gefunden haben. Durch meine Tätigkeit im Scientific and Development Policy Advisory Committee und als Mitherausgeberin des UNYB, das nun unter der Leitung der Stiftung herausgegeben wird, konnte ich eine Verbindung zur Max‑Planck‑Community aufrechterhalten. Diese langjährige Verbindung ist seit über dreißig Jahren eine Bereicherung, welche ich auch in Zukunft zu pflegen versuchen werde.

English

When I came to Germany from my country of origin South Africa in the summer of 1991, there were major changes in the country, the region, and the world. It was the time shortly after German reunification, the collapse of the former Soviet Union, the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq, and the war in the former Yugoslavia. It was also a time of great change and challenges in South Africa as the country prepared for its first democratic elections and the transition from white minority rule to constitutional democracy.

But it was also a time of my own personal intellectual transformation after coming to the Institute (at the time, still housed in Berliner Straße) to do research for my doctoral thesis on the significance of the German Sozialstaatsprinzip (“welfare state principle”) for the future South African constitution. While there had been several South African scholars working at the Institute in the 1980s, during the early 1990s I was one of few South African academics who had the opportunity for a research visit in Heidelberg. I was only 23 years old and had just completed my law degree in Free State, South Africa. For me, the almost two years at the Institute from late summer 1991 to spring 1993 were formative – and a quantum leap in my intellectual development, which ultimately had a decisive impact on my professional career.

Germans Explaining the World? Insights into the Scientific and Discursive Culture at the MPIL in the 1990s

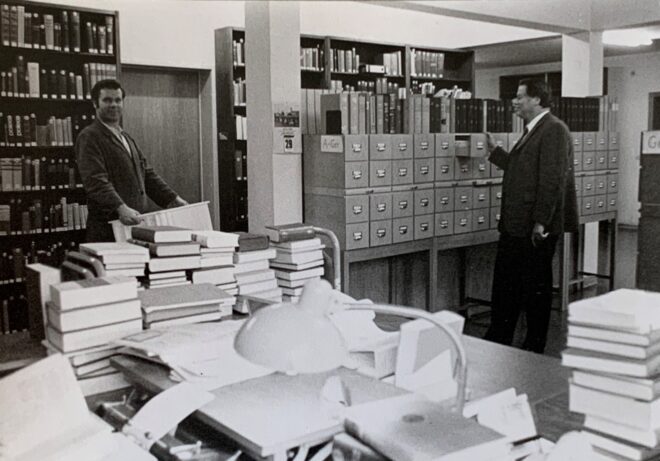

Men in the majority. “Referentenbesprechung” in the institute building in Berliner Straße in 1985 (photo: MPIL)

Coming from a small, regional law faculty in South Africa, at a time when the country was still very isolated politically due to apartheid and academic exchange and critical thinking in South African society faced many obstacles, it is not surprising that I initially found my Heidelberg environment simultaneously intimidating and liberating. My German language skills were still very limited (mainly acquired during two months of intensive study at the Goethe Institute in Schwäbisch Hall in the summer of 1991) and were not yet sufficient to read difficult German legal texts. There were also large gaps in my knowledge and experience in the fields of comparative law, international law, and on how to handle oneself in the environment of international academia. It could therefore be intimidating to discuss a wide range of legal and social issues with the well-educated, often well-travelled and cultured (and at that time predominantly male) academic staff.

Sometimes, however, I did wish that these colleagues would have been more willing to listen with an open mind instead of immediately commenting on highly complex political and legal issues in distant countries – with which they had little personal experience – however well‑read they might have been on a particular topic. At the same time, it was liberating to be in an environment where informed debate was a matter of course. Moreover, these discussions were important for learning to assert myself – often as the only woman in the group (at a time when there was little awareness of the unconscious bias associated with such constellations) – and in a foreign language. Furthermore, my awareness was raised for the importance of robust debate combined with tolerance (including a willingness to listen carefully) to promote nuanced, balanced, and deep academic research. This, in my view, essential quality has, at the time of writing, sadly become increasingly rare even at many elite scholarly institutions, in part due to the destructive influence of social media, which aims to polarise and ‘cancel’, undermining the foundations of academic freedom and democratic discourse.

A Lifelong Connection. The Lasting Influence of the MPIL

Of great significance to me at the time was the close social interaction with the scientific staff and a generally very supportive environment, which was also contributed to by the directors. At the time, the institute was headed by Jochen Abr. Frowein and the late Rudolf Bernhardt. There was also a brief overlap with Rüdiger Wolfrum before my departure in 1993, when he succeeded Rudolf Bernhardt as Director of the Institute. Both Jochen Frowein and Rüdiger Wolfrum remained very interested in and supportive of my career. For example, after the independence of South Sudan in 2011, I had the opportunity to work with Rüdiger Wolfrum and his team in advising on constitutional reform in South Sudan and later Sudan, drawing on South Africa’s experience in the 1990s. It was a great honour for me to take over the editorship of the Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law (UNYB) in 2020 (together with Kathrin Maria Scherr), which had been founded in 1997 by Jochen Frowein and Rüdiger Wolfrum. The influence of their research on my own work and the prominent role of international law in the work of the Institute in general also led to my main research interest shifting from comparative constitutional law to international law over the course of the 1990s.

Another unique aspect of the institute was and is its legendary library collection, both in terms of comparative public law and international law. Researchers (young as well as established) from all over Europe and beyond visited the library, especially during the summer months, resulting in a very lively community of scholars of public law and international law, probably unique in Europe at the time. The ensuing exchange also provided the Institute’s academic staff with a wealth of information that was relevant both for their own research and for the work of the Institute as a whole. The transfer of knowledge that took place in and around the library was therefore a two-way street and of fundamental importance at a time when digital resources and communication were scarce. For me personally, it was also an impetus to gain further international experience and explore new horizons. I was also very fortunate to meet Matthias Herdegen, former research fellow at the Institute and at the time Professor at the University of Konstanz. He established contact due to his interest in the constitutional developments in South Africa and our exchange developed into a lasting collaboration that continues to this day.

Leaving Heidelberg in the spring of 1993 was difficult for me, but I was very fortunate to maintain my connection to the Institute and the city in the years that followed, through subsequent research stays funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and participation in several academic events, as well as via personal contacts that have lasted to this day. In recent years, my ties have also extended to the Max Planck Foundation for International Peace and the Rule of Law, which was founded by Rüdiger Wolfrum in 2013 after his retirement as Director of the institute and whose projects on constitutional reform have received global recognition. Through my work on the Scientific and Development Policy Advisory Committee and as co-editor in chief of the UNYB, which is now published under the auspices of the Foundation, I have been able to maintain a link with the Max Planck community. This long-standing connection has been an enrichment for over thirty years, and I will endeavour to maintain it in the future.

Translation from the German original: Sarah Gebel

Erika de Wet ist Professorin für Völkerrecht und Leiterin des Instituts für Völkerrecht und Internationale Beziehungen an der Universität Graz, Österreich.

Erika de Wet is Professor of International Law and Head of the Department of International Law and International Relations at the University of Graz, Austria.