Deutsch

Das „Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht“ (im Folgenden: Völkerrechts-Institut) ist ein Produkt der Krisen der frühen Weimarer Republik. Gegründet wurde es am 19. Dezember 1924 – als ‚eingetragener Verein’, der mit der Kaiser‑Wilhelm‑Gesellschaft (KWG) in den ersten gut zehn Jahren lediglich assoziiert war.[1] Zurück ging die Entstehung des Instituts auf eine Initiative des am 11. Mai 1920 zum Generalsekretär der KWG berufenen Staats- und Verwaltungsrechtler Friedrich Glum. Aufgabe des Völkerrechts‑Instituts war es, als eine Art brain trust zur außenpolitischen ‚Krisenbewältigung’ beizutragen. Zwar war die verheerende Inflation Ende 1924 gestoppt und die Währung stabilisiert worden, außenpolitisch bewegte sich das Deutsche Reich jedoch weiterhin in höchst unsicheren Fahrwassern. Es war noch nicht in den Völkerbund aufgenommen worden und blieb international weiterhin relativ isoliert. Die Besetzung größerer Teile des Rheinlandes durch französische Truppen hatte nationalistischen Ressentiments im Deutschen Reich kräftige Nahrung gegeben. Nach dem Abbruch des „Ruhrkampfes“ am 26. September 1923 begannen sich die internationalen Konstellationen immerhin allmählich zu entspannen. Das Genfer Protokoll zur „friedlichen Regelung internationaler Streitigkeiten“ wurde am 2. Oktober 1924 unterzeichnet; die Räumung des besetzten Rheinlandes begann im Hochsommer 1925; die Verträge von Locarno Mitte Oktober 1925 bahnten dem Deutschen Reich den Weg in den Völkerbund; formal vollzogen wurde die Aufnahme am 10. September 1926.

Vor diesem Hintergrund war es die zentrale Aufgabe des Völkerrechts‑Instituts „die wissenschaftliche Vorarbeit und Unterstützung für den von der Regierung zu führenden Kampf gegen den Versailler Vertrag, Dawesplan und Youngplan um die völkerrechtliche Gleichberechtigung Deutschlands und der deutschen Minderheiten“ zu leisten.[2] Geleitet wurde die „regierungsnahe Beratungsstelle für Völkerrecht“ (Ingo Hueck) von Viktor Bruns. Bruns, der wenige Tage nach der Gründung ‚seines’ Instituts das 40. Lebensjahr vollendete und seit 1912 Extraordinarius, seit 1920 dann ordentlicher Professor für Staats- und Völkerrecht an der Universität Berlin war, stand bis zu seinem Tod am 28. September 1943 an dessen Spitze.

Dass das Völkerrechts-Institut ‚deutschen Interessen’ gegenüber den angrenzenden europäischen Staaten rechtlich den Weg bahnen sollte, unterstrichen Bruns und seine Mitstreiter, indem sie eine Zweigstelle im französisch besetzten Trier gründeten. Die Mitarbeiter dort widmeten sich seit dem 24. Juli 1925 unter der Leitung des Prälaten Ludwig Kaas der „Auslegung des Versailler Vertrages“, dem „Recht in den besetzten Gebieten [des Rheinlandes], des Saargebietes, Elsaß-Lothringens“ und Südtirols sowie dem „ausländischen Staatskirchenrecht“.[3] Kaas hatte im Herbst 1928 den Vorsitz des Zentrums übernommen und war für die Rechtswende dieser katholischen Volkspartei ab Ende der 1920er Jahre verantwortlich. Am 30. Juni 1933 wurde die Zweigstelle aufgelöst, nachdem Kaas zwei Monate vorher nach Rom emigriert war.

Die Rechtskonstruktion des Instituts und seine ‚Anlehnung’ an die renommierte KWG brachte beträchtliche politische Vorteile mit sich: Zwar war Bruns’ Institut de facto eine Gutachter- und Beratungseinrichtung, vor allem des Auswärtigen Amtes, und Bruns zudem der wichtigste Repräsentant des Deutschen Reichs vor dem Internationalen Gerichtshof in Den Haag, der Form nach war und blieb es jedoch eine unabhängige Einrichtung. Seine Expertisen konnten ‚neutralen‘ Charakter beanspruchen und liefen nicht Gefahr, parteipolitischen Auseinandersetzungen zum Opfer zu fallen; der Direktor und seine Mitarbeiter waren nicht von den kurzlebigen Regierungskoalitionen abhängig. Auch international ließen sich die Gutachten eines nominell unabhängigen Instituts wirkungsvoller einsetzen.

Das Institut im Dritten Reich. Wissenschaftliche Begleitung des neuen deutschen Imperialismus

Aufzug vor dem Alten Museum. “Sieghafter Einzug der Spanischen Legion Condor“. Blick von den oberen Etagen des Berliner Schlosses, jedoch nicht von den Institutsräumen: 06.06.1939[4]

Das Jahr 1933 markiert für das Völkerrechts-Institut in mehrerlei Hinsicht einen Einschnitt. Demokraten wie Carlo Schmid hatten das Institut schon vorher verlassen, andere folgten nach 1933. Der nach den NS-Rassegesetzen als Jude geltende und seit 1927 als Wissenschaftlicher Berater des Instituts tätige Erich Kaufmann musste 1934 diese Stellung aufgeben; er floh in die Niederlande und überlebte dort, teils in der Illegalität, den Krieg. Auch Marguerite Wolff überlebte die NS-Zeit. Sie war bei der Gründung des Instituts von Bruns als wissenschaftliche Assistentin eingestellt worden und wurde aufgrund ihrer jüdischen Herkunft im April 1933 entlassen. Ähnlich ihr gleichfalls jüdischer Ehemann Martin Wolff, der Ende 1925 zum Wissenschaftlichen Mitglied des Zwillings-Instituts für Privatrecht berufen worden war. Mitte der 1930er Jahre emigrierte das Ehepaar nach England. Zu den aus rassistischen Gründen NS‑Verfolgten gehört im Weiteren auch Gerhard Leibholz, ein Mitarbeiter aus der Anfangszeit des Völkerrechts-Instituts, der als Jude diskriminiert noch wenige Wochen vor dem Novemberpogrom 1938 ebenfalls nach England fliehen konnte.

Die Ernennung Hitlers zum Reichskanzler und der Austritt Deutschlands aus dem Völkerbund hatten eine Art politisch-juristischen Paradigmenwechsel zur Folge: Bis 1933 hatte das Völkerrechts-Institut vor allem die Kriegsfolgen mit Gutachten etc. rechtlich abzufedern und rückgängig zu machen versucht. 1933 begaben sich auch das Institut und seine führenden Exponenten auf den aggressiv-imperialen Kurs, den das NS-Regime schon bald einschlug; sie taten dies, ohne dazu gezwungen werden zu müssen – und wuchsen damit in eine zentrale Rolle für das NS-Regime hinein: Als juristisches Beratungsorgan blieb das Institut „im Auswärtigen Amt tonangebend“.[5]

Wo die zentralen Akteure politisch standen, zeigten sie mit ihrem Engagement für Aufrüstung und imperiale Ziele: Viktor Bruns etwa engagierte sich in starkem Maße für die auf diesem Feld besonders eifrige, am 28. Juni 1933 gegründete „Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wehrpolitik und Wehrwissenschaften“ (DGWW); ebenso Ernst Schmitz, seit 12. Mai 1931 Leiter der völkerrechtlichen Abteilung und vom 11. Januar 1936 bis zu seinem Tod Anfang 1942 als enger Vertrauter Bruns’ der stellvertretende Direktor des Völkerrechts-Instituts. Bruns und Schmitz, ein Spezialist für Kriegsrecht, hielten im Auftrag der Gesellschaft militärpolitische Vorträge und gaben der „wehrwissenschaftlichen“ Gesellschaft damit einen seriösen und über Partikularinteressen stehenden Anstrich. Beide galten als zentrale Stützen der DGWW.[6] Und ebenso der, wie Friedrich Glum es formulierte, „faszinierende Staatsrechtslehrer“ Carl Schmitt, den Bruns Anfang Dezember 1933 als „wissenschaftlichen Berater“ an das Institut band. Schmitt, Vordenker der 1930 etablierten Präsidialdiktatur und 1932 Vertreter der Papen-Regierung im „Preußenschlag“-Prozess vor dem Staatsgerichtshof, hielt auf der zweiten Hauptversammlung der DGWW 1934 den zentralen Vortrag.[7]

Das Völkerrechts-Institut war nicht nur mit Vereinigungen, die Aufrüstung und Bellizismus, durchaus auch im Wortsinne, ‚predigten’, eng vernetzt. Auch personell erhielt das Institut ein markant militärisches Gesicht, vor allem sein Aufsichtsgremium: Anfang 1937, nachdem wenige Monate zuvor die Phase der forcierten Aufrüstung offiziell verkündet worden war, wurden in das gemeinsame Kuratorium der beiden Rechts-Institute hochrangige Militärs gewählt, nämlich Reichskriegsminister und Generalfeldmarschall Werner von Blomberg (mit dem Recht, sich vertreten zu lassen), der langjährige Vorsitzende der DGWW General Friedrich von Cochenhausen, der (Anfang 1939 reaktivierte) Admiral a.D. Walter Gladisch sowie der General der Flieger (und spätere Generalfeldmarschall) Erhard Milch.[8]

Pluralismus dank Pragmatismus? Konservative und völkische Standpunkte am KWI

Mitarbeiter des Instituts auf dem Dach des Berliner Schlosses: vl. n. r: Joachim-Dieter Bloch, Ursula Grunow, Alexander N. Makarov, Hermann Mosler (undatiert)[9]

Bemerkenswert ist, dass trotz des angedeuteten Paradigmenwechsels der innere Pluralismus des Instituts auch nach 1933 erhalten blieb – wenn auch innerhalb des vom NS-Regime gesetzten politischen Rahmens, also deutlich nach rechts verschoben: Manche verfolgten weiterhin das Konzept einer – grundsätzlich gleichberechtigten – „Völkerrechtsgemeinschaft“, andere die Idee einer rassistisch‑hierarchischen „Völkergemeinschaft“. Zu letzteren gehörte etwa Herbert Kier, der bereits 1931 der NSDAP beitrat, von 1932 bis 1934 sogar deren österreichischer Landesleitung angehörte (jedoch nicht der SS beitrat) und seit Oktober 1933 als zunächst vorübergehend, seit Herbst 1935 dann dauerhaft Experte für „Volksgruppenrecht“ im Völkerrechts-Institut arbeitete. Diese weiterhin deutliche Spannbreite unterschiedlicher Vorstellungen über Form und Funktion des Völkerrechts hatte zwei Gründe:

Zum einen sollte die traditionelle, stark ‚wilhelminisch grundierte‘ und bildungsbürgerlich geprägte Juristenelite nicht vor den Kopf gestoßen werden. Zahllose Justiz- und Verwaltungsjuristen und ebenso Exponenten der Rechtswissenschaften standen – wie die hohen NSDAP‑Mitgliedszahlen unter ihnen ausweisen – der NS-Bewegung zwar politisch‑weltanschaulich oft sehr nah; sie blieben jedoch zu einem erheblichen Teil weiterhin zu stark klassisch‑juristischen Denkmustern verhaftet, als dass man ihnen binnen kurzer Zeit die obskure ‚rassengesetzliche Rechtslehre‘ von rassistischen Eiferern wie Kier hätte oktroyieren können. ‚Verprellen‘ wollte man die im Wilhelminischen sozialisierten Rechtswissenschaftler jedoch auch nicht, und zwar nicht nur, weil deren politisch‑weltanschauliche Ansichten sich stark mit der Hitler-Bewegung und dem (ebenfalls selbst ideologisch keineswegs homogenen) NS-Regime überschnitten. Die Exponenten der Diktatur brauchten auch und gerade die Wissenschaftseliten, um ‚funktionale‘ Lösungen sowohl zur (in unserem Fall: Rechtsbasierung der) innenpolitischen Konsolidierung als auch für die Umsetzung der von Anbeginn avisierten imperialen Expansion zu finden.

Es war des Weiteren ein eigentümlicher ‚Pragmatismus’ der Protagonisten des NS-Regimes, der hinter der deutlichen Spannbreite unterschiedlicher Vorstellungen über Form und Funktion des Völkerrechts nach 1933 stand. Sie konnten sich so die jeweils funktionalsten, unter den ihnen präsentierten gutachterlichen ‚Lösungen’ für mit dem Völkerrecht verquickte außenpolitische ‚Probleme’ aussuchen. Dies ist der zweite Grund für den – relativen – Pluralismus innerhalb (auch) der Rechtswissenschaften und erklärt, warum sich führende Akteure des Regimes politisch‑administrativ nicht in die Forschungskontroversen des jeweiligen Wissenschaftsfeldes einmischten.

Die, bei den exponierten Persönlichkeiten des Instituts deutlich erkennbare, Selbstmobilisierung zur rechtlichen Fundierung und Durchsetzung der imperialen Ziele der NS-Diktatur schloss im Übrigen Reibungen und Rivalitäten mit ähnlich gelagerten Institutionen keineswegs aus: Seit dem 9. April 1935 firmierte das Völkerrechts- Institut förmlich als „Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut“, ebenso die „Schwesteranstalt“ für ausländisches Privatrecht. Damit kam die KWG einem Übernahmeversuch der am 26. Juni 1933 gegründeten „Akademie für Deutsches Recht“ zuvor. Am 30. Mai 1938 wurde dann auch der bisherige gemeinsame Trägerverein aufgelöst und beide Rechtsinstitute vollständig in die KWG integriert.

Der veränderte Status des Instituts ist kein Indiz für politisch-ideologisch oppositionelle oder gar widerständige Haltungen seiner Akteure, sondern eines von zahllosen Beispielen für systemtypische Konkurrenzen um Macht und Einfluss. Auch der herausragende Stellenwert der KWG samt ihren Instituten für das NS-Regime lässt sich daran ablesen, dass die Autonomie der Wissenschaftsgesellschaft bis 1945 unangetastet blieb. Das galt ebenso für das Völkerrechts-Institut. Das Engagement sowohl für das Völkerrechts-Institut als auch für die „Akademie für Deutsches Recht“ ließ sich im Übrigen individuell problemlos miteinander vereinbaren. Namentlich Bruns prägte ebenso die „Akademie für Deutsches Recht“ als Vorsitzender des Ausschusses für Völkerrecht; außerdem war er Mitglied im Ausschuss für Nationalitätenrecht. So können denn auch entsprechende politische Positionierungen nicht überraschen: Viktor Bruns etwa polemisierte in seinem Vortrag auf der 27. Ordentlichen Hauptversammlung der KWG im Mai 1938 in nicht misszuverstehender Deutlichkeit zunächst gegen den Versailler Vertrag und sonstige „skrupellose Rechtsverletzungen“ der Siegermächte. Am Schluss seines Vortrags unter dem Titel „Die Schuld am ‚Frieden‘ und das deutsche Recht am Sudetenland“ rechtfertigte er die vier Monate später vollzogene Okkupation der zur CSR gehörenden Region, indem er „das trübe Bild einer noch nicht lange hinter uns liegenden Vergangenheit“ mit dem vorgeblich hellen Bild der Gegenwart und Zukunft kontrastierte:

„Das Bild der Gegenwart ist ein anderes; das deutsche Volk hat einen Führer; die Deutschen in Böhmen sind geeint und organisiert, sie stellen eine Volksbewegung von wirklicher Kraft dar. Damit ist auch diese Voraussetzung [eine fehlende politische Geschlossenheit] für die Eingliederung der Sudetendeutschen in den tschechischen Staat dahingefallen.“[10]

Bruns sprach keineswegs nur für sich. Dies zeigt der Blick in das Jahrbuch der KWG von 1939. Im dort veröffentlichten Rechenschaftsbericht der Generalverwaltung heißt es, Bruns’ Vortrag sei von „geradezu historischer Bedeutung […], wurde hier [doch] bereits in unwiderleglicher Weise der deutsche Rechtsanspruch auf eine Neuregelung im böhmisch‑mährischen Raum erhoben und die völkerrechtliche Grundlage für die späteren Maßnahmen [!] des Führers klargestellt.“[11]

Seit den Vorkriegsjahren gestaltete sich die Kooperation des Völkerrechts-Instituts, das in den 1930er Jahren durchgängig zwischen fünfzig und sechzig Mitarbeiter beschäftigte, mit dem NS-Außenministerium und (das ist bisher nicht erforscht[12]) vermutlich auch mit anderen außenpolitisch aktiven Institutionen und Organisationen der Diktatur immer enger. Gleichwohl behielt es seine Selbständigkeit, nicht nur organisatorisch, sondern auch inhaltlich. Es war eine exkulpatorische Schutzbehauptung, wenn Bruns’ Nachfolger Bilfinger am 17. Juli 1947 vor der Spruchkammer in Heidelberg behauptete, sein Institut sei „im Kriege mehr oder weniger eine Filiale des Auswärtigen Amtes gewesen“.[13] Solche Formeln sollten die eigene willige Selbstmobilisierung für die Diktatur kaschieren und zudem vergessen machen, dass das NS-Herrschaftssystem keineswegs monolithisch war.

Die zweifellos vorhandene Bindung an das Auswärtige Amt hatte sozialstrukturelle Folgen: Viele Mitarbeiter des Instituts wechselten in den diplomatischen Dienst oder gehörten gleichzeitig dem Auswärtigen Amt sowie den Stellen der Reichswehr an, die auch Fragen des Völkerrechts zu thematisieren hatten. Infolgedessen glich die Struktur des Völkerrechts‑Instituts tendenziell der des diplomatischen Dienstes: Stärker als in anderen KWI waren unter den Mitarbeitern und Wissenschaftlichen Mitgliedern Adlige vertreten. Zudem „dominierte ein gewisser gesellschaftlicher Dünkel“.[14]

Denunziation und Widerstand. Das Institut am Kriegsende

Ein prominenter Adliger war Berthold Schenk von Stauffenberg, der zum Kreis um Stefan George gehört hatte und einer von dessen Nachlassverwaltern war. Von Stauffenberg hatte eine erste Gesamtdarstellung des internationalen Prozessrechtes verfasst, arbeitete bereits 1929/30 kurzzeitig am Völkerrechts‑Institut und wurde, gerade 30 Jahre alt geworden, am 25. Juni 1935 dort zum Wissenschaftlichen Mitglied ernannt. Am 1. April 1937 avancierte von Stauffenberg zum Leiter der neu eingerichteten Abteilung für „Kriegs- und Wehrrecht“. Als Experte für Seekriegsrecht wurde von Stauffenberg Ende 1939 in das Oberkommando der Marine berufen und war seitdem nur noch selten im Berliner Völkerrechts-Institut. Er blieb aus einer hochkonservativen Haltung heraus dem Dritten Reich „bis in die Kriegsjahre hinein verpflichtet“, ehe er sich ab 1941/42 – nach dem Überfall auf die Sowjetunion und dem offensichtlichen Bruch mit allen völker- und kriegsrechtlichen Regelungen – dem Konservativen Widerstand anschloss. Nach dem Attentat seines Bruders Claus auf Hitler wurde er verhaftet und am 10. August 1944 hingerichtet. Zur Widerstandsbewegung des 20. Juli 1944 gehörte auch Helmuth Graf James von Moltke; auch er war seit Kriegsbeginn in der „Beratungsstelle für Völkerrecht“ im „Amt Ausland/Abwehr“ des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht beschäftigt und wurde am 2. Februar 1945 hingerichtet.

Von Stauffenbergs und von Moltkes Tätigkeit für das Völkerrechts-Institut machten aus dem KWI „nicht eine Institution der Widerstandsbewegung des 20. Juli 1944“ (Hueck).[15] Dass mindestens in den letzten Kriegsjahren die Atmosphäre am KWI von Denunziantentum und Misstrauen geprägt war, illustriert die ‚Affäre Wengler’: Wilhelm Wengler, der in der Bundesrepublik als einer der renommiertesten Universitätslehrer für internationales Recht und Rechtsvergleichung galt, war von 1933 bis 1938 Referent zunächst am KWI für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht gewesen und wechselte dann ans Völkerrechts‑Institut. Wengler, der im Herbst 1942 – ohne wie die Vorgenannten seine Tätigkeit für das KWI aufzugeben – als Referent für Völkerrecht zum Oberkommando der Wehrmacht sowie zur Kriegsmarine abgeordnet wurde, blieb dort in Kontakt mit seinen Kollegen von Moltke und von Stauffenberg. Im Oktober 1943 denunzierte der am Völkerrechts-Institut beschäftigte wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiter und gleichzeitige „Vertrauensmann des Sicherheitsdienstes am Institut“ Herbert Kier Wengler wegen „defätistischer Äußerungen“. Am 14. Januar 1944 wurde Wengler von der Gestapo verhaftet. Er hatte im Unterschied zu von Moltke und von Stauffenberg ‚Glück im Unglück’: Mitte November 1944 wurde Wengler zur Wehrmacht eingezogen und überlebte den Krieg.[16]

Schon vorher, ab Sommer 1944, hatte das Institut begonnen, seine Aktivitäten wegen immer massiverer Luftangriffe in Außenstellen innerhalb Berlins zu verlegen. Teile der Bibliothek wurden in das Berliner Umland ausgelagert. Am 3. Februar 1945 wurden Räumlichkeiten des Völkerrechts-Instituts im Stadtschloss zerstört und auch der größte Teil der Bibliothek sowie der Akten vernichtet; der Rest wurde im Privathaus von Viktor Bruns untergebracht.

Nachfolger von Bruns als KWI-Direktor war am 1. November 1943 Carl Bilfinger geworden, von 1924 bis 1935 Professor für Staats‑ und Völkerrecht in Halle, von 1935 bis 1943 in Heidelberg. Umstritten war Bilfinger während der Nachkriegszeit aufgrund seiner politischen Belastung im Dritten Reich. Die Folge waren heftige vergangenheitspolitische Turbulenzen. Bilfinger musste sein Amt Anfang Juli 1946 niederlegen und sich erst einmal durch ein Entnazifizierungsverfahren „weißwaschen“ lassen. Die kommissarische Leitung des zunächst der Deutschen Forschungshochschule in Berlin angegliederten Völkerrechts-Instituts übernahm Karl von Lewinski.[17] Vom 18. März 1949 bis Anfang 1954 leitete Bilfinger erneut das Institut, nun als Max‑Planck‑Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, das seinen Sitz in Heidelberg, der Heimatstadt Bilfingers, nahm. Demokratische Juristen und Politiker wie Adolf Grimme hielten die erneute Berufung Bilfingers zum Direktor des Völkerrechts‑Instituts aufgrund von dessen NS‑Belastungen für einen „ernsten politischen und sachlichen Fehler“.[18] Der NS-Verfolgte Gerhard Leibholz und viele andere kritisierten die Entscheidung noch schärfer. Der MPG-Senat setzte sie dennoch durch. Erst die Ernennung Hermann Moslers am 29. Januar 1954 markiert den Bruch mit der NS-Vergangenheit des Instituts.

[1] Zur Gründungsgeschichte des Instituts: Ingo Hueck, Die deutsche Völkerrechtswissenschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Das Berliner Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, das Hamburger Institut für Auswärtige Politik und das Kieler Institut für Internationales Recht, in: Doris Kaufmann (Hrsg.), Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus, Bd. 2, Göttingen: Wallstein 2000, 490-527 (499 ff.); Rüdiger Hachtmann, Wissenschaftsmanagement im „Dritten Reich“. Geschichte der Generalverwaltung der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, Bd. 1, Göttingen: Wallstein 2007, 110 ff.

[2] Friedrich Glum, Denkschrift über die Notlage der Forschungsinstitute der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, 2. Sepember 1932, BArch,, R 2/12019, Bl. 14, 4.

[3] Zitate von Viktor Bruns nach: Nelly Keil, Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft in Gefahr, in: Germania ‑ Zeitung für das Deutsche Volk, 25. Dezember 1932.

[4] AMPG, VI. Abt., Rep. 1, Nr. KWIauslöffRechtuVölkerrecht II/6. Fotograf/in unbekannt, vermutlich aber aus dem Institut.

[5] Hueck (Fn. 1), 503.

[6] Vgl. Peter Kolmsee, Die Rolle und Funktion der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Wehrpolitik und Wehrwissenschaften bei der Vorbereitung des Zweiten Weltkrieges durch das faschistische Deutschland, unv. Diss., Universität Leipzig 1966, „Biographischer Anhang der wichtigsten Mitglieder der DGWW”, 3, 14. Die Mitgliederliste liest sich wie ein who is who der rechtskonservativen und frühfaschistischen Bündnispartner der NS-Bewegung; Zu den, lange Zeit engen, Beziehungen zwischen der DGWW und der Generalverwaltung der KWG: Vgl. Hachtmann (Fn. 1), Bd. 1, 480-485.

[7] Vgl. die entsprechende Einladung an Glum und die Generalverwaltung, MPG-Archiv, Abt. I, Rep.1A, Nr. 900/1, Bl. 18.

[8] Aktenvermerk Glums vom 14. Jan. 1937 über eine Besprechung vom 9. Jan. mit Bruns, MPG-Archiv, Abt. I, Rep. 1A, Nr. 2351/4, Bl. 180.

[9] AMPG, VI. Abt., Rep. 1, Nr. KWIauslöffRechtuVölkerrecht III/51.

[10] Ernst Telschow (Hrsg.), Jahrbuch 1939 der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, Leipzig: Drugulin 1939, 57-85 (Zitat: 85).

[11] Telschow (Fn. 10), 52.

[12] Innerhalb des Forschungsprogramms der MPG-Präsidentenkommission zur Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus war das Institut leider nicht Gegenstand eines eigenständigen Forschungsprojektes. Der Aufsatz von Hueck (Fn. 1) bietet allerdings wichtige Eckpflöcke für ein künftiges Projekt.

[13] Zitiert nach: Richard Beyler, „Reine Wissenschaft“ und personelle Säuberungen. Die Kaiser-Wilhelm-/ Max-Planck-Gesellschaft 1933 und 1945, Berlin: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften 2004, 30 f.

[14] Hueck (Fn. 1), 510.

[15] Hueck (Fn. 1), 522.

[16] Ausführlich zu dieser Affäre: Hachtmann (Fn. 1), Bd. 2, 1147-1156.

[17] Von Lewinski (1873-1951) vertrat von 1922 bis 1931 das Deutsche Reich bei den Reparationsverhandlungen in Washington D.C. Danach war er bis 1945 als Rechtsanwalt in Berlin tätig.

[18] Adolf Grimme an Otto Hahn, 14. Juli 1950, zitiert nach: Beyler (Fn. 13), 33; Zu den weiteren Kritiken an der erneuten Berufung Bilfingers: Vgl. Felix Lange, Carl Bilfingers Entnazifizierung und die Entscheidung für Heidelberg. Die Gründungsgeschichte des völkerrechtlichen Max-Planck-Instituts nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, ZaöRV 74 (2014), 697-731, 721 ff.

|

Suggested Citation: Rüdiger Hachtmann, Das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht 1924 bis 1945, DOI: 10.17176/20240403-184342-0 |

|

| Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED | |

English

The “Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law” (hereinafter: International Law Institute) is a product of the crises of the early Weimar Republic. It was founded on 19 December 1924 as a ‘registered association’ (eingetragener Verein), which was merely associated with the Kaiser‑Wilhelm‑Society (Kaiser‑Wilhelm‑Gesellschaft, KWG) for the first ten years.[1] The Institute was founded on the initiative of Friedrich Glum, who was appointed Secretary General of the KWG on 11 May 1920. The task of the International Law Institute was to contribute to foreign policy ‘crisis management’ as a kind of “brain trust”. Although the devastating inflation had been stopped in late 1924 and the currency stabilised, the German Reich continued to move in highly uncertain waters in terms of foreign policy. It had not yet been admitted to the League of Nations and remained relatively isolated internationally. The occupation of large parts of the Rhineland by French troops had fuelled nationalist resentment in the German Reich. After the Ruhrkampf ended on 26 September 1923, international constellations gradually began to relax. The Geneva Protocol on the “peaceful settlement of international disputes” was signed on 2 October 1924; the evacuation of the occupied Rhineland began in midsummer 1925; the Locarno Accords in mid-October 1925 paved the way for the German Reich to join the League of Nations; the admission was formally completed on 10 September 1926.

Against this background, the central task of the International Law Institute was to provide “scientific preparatory work and support for the struggle to be waged by the government against the Versailles Treaty, Dawes Plan, and Young Plan for equal rights under international law of Germany and the German minorities”[2]. The “government-related advisory office for international law” (Ingo Hueck) was led by Viktor Bruns. Bruns, who reached the age of 40 a few days after the founding of ‘his’ institute and had been an associate professor at the University of Berlin since 1912, then an ordinary professor of constitutional and international law since 1920, was director of the institute until his death on 28 September 1943.

Bruns and his colleagues underlined the fact that the International Law Institute was to pave the legal way for ‘German interests’ vis-à-vis the neighbouring European states by founding a branch office in French-occupied Trier. Since 24 July 1925, the staff there, under the direction of prelate Ludwig Kaas, devoted themselves to the “interpretation of the Treaty of Versailles”, the “law in the occupied territories [of the Rhineland], the Saar region, Alsace-Lorraine”, and South Tyrol, as well as “foreign state church law”.[3] Kaas had taken over the chairmanship of the Centre Party (Deutsche Zentrumspartei) in autumn of 1928 and was responsible for the political turn to the right of this Catholic people’s party from the end of the 1920s onwards. On 30 June 1933, the branch office was terminated after Kaas had emigrated to Rome two months earlier.

The legal construction of the Institute and its ‘affiliation’ with the renowned KWG entailed considerable political advantages: although Bruns’ Institute was de facto an institution for the delivery of legal opinions and advisory, primarily to the Foreign Office, and Bruns was also the most important representative of the German Reich before the International Court of Justice in The Hague, it was and remained a formally independent institution. Its expert opinions could claim a ‘neutral’ character and did not run the risk of falling victim to party‑political disputes; the director and his staff were not dependent on short-lived government coalitions. Additionally, the expert opinions of a nominally independent institute could be used more effectively in an international context.

The Institute in the Third Reich. Scientific Support for the New German Imperialism

Parade in front of the Altes Museum: “Victorious entry of the Spanish Condor Legion”. View from the upper floors of the Berlin Palace, but not from the institute rooms: 06.06.1939[4]

The year 1933 marked a turning point for the International Law Institute in several respects. Democrats such as Carlo Schmid had already left the Institute before, others followed after 1933. Erich Kaufmann, who had been working as a scientific advisor to the Institute since 1927, had to give up this position in 1934, as he was considered a Jew according to the Nuremberg Laws; he fled to the Netherlands and survived the war there, partly in illegality. Marguerite Wolff also survived the Nazi era. She had been hired by Bruns as a research assistant when the Institute was founded and was dismissed in April 1933 because of her Jewish origin. Similarly, her husband Martin Wolff, who was also Jewish, had been appointed Scientific Member of the twin-institute for private law at the end of 1925. In the mid-1930s, the couple emigrated to England. Gerhard Leibholz, a staff member from the early days of the International Law Institute, who was discriminated against as a Jew and was able to flee to England just a few weeks before the November pogrom in 1938, was also among those persecuted on racist grounds.

Hitler’s appointment as chancellor and Germany’s withdrawal from the League of Nations resulted in a kind of political-legal paradigm shift: until 1933, the International Law Institute had mainly tried to soften and undo the legal consequences of the war by means such as legal opinions. From 1933 onwards, the institute and its leading exponents also embarked on the aggressive‑imperial course that the Nazi regime soon took; they did so without having to be forced – and, thus, grew into a central role for the Nazi regime: as a legal advisory body, the institute continued to “set the tone in the Foreign Office”.[5]

Where the central actors stood politically was shown by their commitment to rearmament and imperial goals: Viktor Bruns, for example, was heavily involved with the “German Society for Military Policy and Military Science” (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wehrpolitik und Wehrwissenschaften, DGWW), founded on 28 June 1933, which was particularly zealous in this field. Likewise, Ernst Schmitz was head of the international law department from 12 May 1931 and, as Bruns’ close confidant from 11 January 1936 until his death in early 1942, he was deputy director of the International Law Institute. Bruns and Schmitz, a specialist in the law of war, gave lectures on military policy on behalf of the society, thus giving the “Military Science” Society a veneer of integrity and distance to party interests. Both were regarded as central pillars of the DGWW.[6] And so was the, as Friedrich Glum put it, “fascinating teacher of constitutional law” Carl Schmitt, whom Bruns tied to the Institute as a “scientific advisor” at the beginning of December 1933. Schmitt, who had paved the way intellectually for the presidential dictatorship established in 1930 and was the representative of the Papen government in the “Preußenschlag” trial before the State Court in 1932, gave the central lecture at the second general meeting of the DGWW in 1934. [7]

The International Law Institute was not only closely intertwined with associations that ‘preached’, at times in the literal sense, rearmament and bellicism. In terms of personnel, the institute also acquired a decisively military character, especially its supervisory body: in the beginning of 1937, after the phase of accelerated rearmament had been officially announced a few months earlier, high-ranking military officers were elected to the joint board of trustees of the two law institutes, namely Reich Minister of War and Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg (with the right to be substituted), the long-standing chairman of the DGWW General Friedrich von Cochenhausen, the retired Admiral Walter Gladisch (reactivated at the beginning of 1939), and Air Force General (and later General Field Marshall) Erhard Milch. [8]

Pluralism due to Pragmatism? Conservative and Völkisch Viewpoints at the KWI

Employees of the Institute on the roof of the Berlin Palace (undated): from left to right: Joachim-Dieter Bloch, Ursula Grunow, Hermann Mosler, Alexander N. Makarov[9]

It is remarkable that, despite the paradigm shift alluded to, the inner pluralism of the Institute remained intact after 1933 – albeit within the political framework set by the Nazi regime, i.e., clearly shifted to the right: Some continued to pursue the concept of a – fundamentally equal – “community of international law”, others the idea of a “community of nations” (Völkergemeinschaft) based on a racial hierarchy. The latter included Herbert Kier, for example, who joined the NSDAP as early as 1931 and had been an expert on “ethnic group law” (Volksgruppenrecht) at the Institute of International Law since 1936. There were two reasons for the continuation of a range of different ideas about the form and function of international law:

On the one hand, the traditionally educated bourgeois legal elite, which had a strong ‘Wilhelminian’ ethos, was not to be affronted. Numerous lawyers working in the judiciary and the administration as well as exponents of jurisprudence were – as the high NSDAP membership figures among them show – politically and ideologically very close to the Nazi movement. However, a considerable number of them remained too attached to traditional legal thought patterns for the obscure “racial law legal doctrine” (rassengesetzliche Rechtslehre) of racist zealots like Kier to be imposed on them within a short time. However, one did not want to ‘alienate’ the legal scholars who had been socialised in the Wilhelminian era, and not only because their political‑ ideological views overlapped strongly with the Hitler movement and the Nazi regime (which itself was by no means ideologically homogeneous). The exponents of the dictatorship also needed the scientific elites in particular to find ‘functional’ solutions both for (in our case: law-based) domestic political consolidation and for the implementation of the imperial expansion that had been envisaged from the very beginning.

It was furthermore a peculiar ‘pragmatism’ of the protagonists of the Nazi regime that was behind the considerable range of different ideas about the form and function of international law after 1933. This way, political actors were able to choose the most functional of the expert ‘solutions’ presented to them for foreign policy ‘problems’ entangled with international law. This is the second reason for the – relative – pluralism within the legal sciences (among other fields) and explains why leading actors of the regime did not interfere in the controversies of the respective scientific field with political or administrative means.

The self-mobilisation for the legal grounding and implementation of the imperial goals of the Nazi dictatorship, which is clearly observable among the International Law Institute’s prominent personalities, by no means ruled out friction and rivalries with similarly positioned institutions: since 9 April 1935, the International Law Institute formally operated under the name “Kaiser Wilhelm Institute”, as did its “sister institute” for foreign private law. In this way, the KWG preempted a take-over attempt by the Academy for German Law (Akademie für Deutsches Recht), which had been founded on 26 June 1933. On 30 May 1938, the former joint sponsoring association was dissolved and both legal institutes were fully integrated into the KWG.

The changed status of the Institute is not an indication of political or ideological opposition or even resistant attitudes of its actors, but one of countless examples of competition for power and influence typical of the political system. The outstanding importance of the KWG and its institutes for the Nazi regime can also be deducted from the fact that the autonomy of the scientific society remained untouched until 1945. This also applied to the International Law Institute. Incidentally, the commitment to both the International Law Institute and the Academy for German Law could be reconciled without any problems. Bruns, in particular, also left his mark on the Academy for German Law as chairman of the Committee for International Law; he was further a member of the Committee for Nationality Law.

Thus, corresponding political positions are not surprising: Viktor Bruns, for example, in his lecture at the 27th Ordinary General Meeting of the KWG in May 1938, polemicized in no uncertain terms against the Treaty of Versailles and other “unscrupulous violations of law” by the allied powers. At the end of his lecture under the title “The Blame for ‘Peace’ and German Right to the Sudetenland” (“Die Schuld am ‘Frieden’ und das deutsche Recht am Sudetenland”), he justified the occupation of the region belonging to the RČS, which was carried out four months later, by contrasting “the bleak picture of a past not long behind us” with the ostensibly bright picture of the present and future:

“The picture of the present is different; the German people have a Führer; the Germans in Bohemia are united and organised, they represent a popular movement of real strength. Thus, this precondition [a lack of political unity] for the integration of the Sudeten Germans into the Czech state has also fallen away.”[10]

Bruns was by no means speaking only for himself. This is illustrated by taking a look at the 1939 KWG yearbook, where the accountability report of the general administration states that Bruns’ lecture was of “almost historical significance […], since here the German legal claim to a new settlement in the Bohemian-Moravian area was already irrefutably raised and the basis in international law for the Führer’s later measures [!] was clarified”. [11]

Since the pre-war years, the cooperation of the International Law Institute, which in the 1930s consistently employed between fifty and sixty staff members, with the Nazi Foreign Office and (this has not yet been researched[12] ) presumably also with other institutions and organisations of the dictatorship active in foreign policy, became ever closer. Nevertheless, it retained its independence, not only organisationally but also scientifically. It was an exculpatory protective claim when Bruns’ successor Bilfinger asserted before the Heidelberg criminal court on 17 July 1947 that his institute had “more or less been a branch of the Foreign Office during the war”.[13] Such formulas were intended to conceal one’s own willing self-mobilisation for the dictatorship as well as the fact that the Nazi system of rule was by no means monolithic.

The undoubtedly existing ties to the Foreign Office had socio-structural consequences: many of the institute’s staff transferred to the diplomatic service or belonged simultaneously to the Foreign Office or to army offices which also had to address issues of international law. As a result, the structure of the International Law Institute tended to resemble that of the diplomatic service: members of the old German nobility were more strongly represented among the staff and academic members than in other KWIs. In addition, “a certain social conceit” (Ingo Hueck) dominated.[14]

Denunciation and Resistance. The Institute at the End of the War

One prominent nobleman was Berthold Schenk von Stauffenberg, who had belonged to Stefan George’s circle and was one of his testamentary executors. Von Stauffenberg had written the first comprehensive treatise on international procedural law, worked briefly at the International Law Institute in 1929/30 and, having just turned 30, was appointed a Scientific Member there on 25 June 1935. On 1 April 1937, von Stauffenberg was promoted to head of the newly established department for “Law of War and Military Law”. As an expert on the law of naval warfare, von Stauffenberg was appointed to the High Command of the Navy at the end of 1939 and rarely visited at the Berlin International Law Institute thereafter. Out of a starkly conservative stance, he remained “committed [to the Third Reich] well into the war years” before joining the Conservative Resistance from 1941/42 – after the invasion of the Soviet Union and the obvious break with all rules of international law. After his brother Claus’ assassination attempt on Hitler, he was arrested and executed on 10 August 1944. Helmuth Graf James von Moltke also belonged to the resistance movement of 20 July 1944; he too had been employed since the beginning of the war in the Advisory Office for International Law at the “Office of the Exterior/ Defence” of the High Command of the Wehrmacht and was executed on 2 February 1945.

Von Stauffenberg’s and von Moltke’s activities for the International Law Institute did not make it “an institution of the resistance movement of 20 July 1944” (Hueck).[15] The fact that the atmosphere at the KWI was characterised by denunciation and mistrust, at least in the last years of the war, is illustrated by the ‘Wengler Affair’: Wilhelm Wengler, who was considered one of the most renowned university lecturers on international law and comparative law in the post-war Federal Republic of Germany, had first been a lecturer at the KWI for Comparative and International Private Law from 1933 to 1938 and then moved to the International Law Institute. Wengler, who in autumn 1942 – without giving up his work for the institute such as the aforementioned – was seconded to the High Command of the Wehrmacht and the Navy (Kriegsmarine) as a consultant for international law, remained in contact with his colleagues von Moltke and von Stauffenberg. In October 1943, Herbert Kier, a research assistant at the Institute of International Law and at the same time “confidant of the security service at the institute”, denounced Wengler for “defeatist statements”. On 14 January 1944, Wengler was arrested by the Gestapo. Unlike von Moltke and von Stauffenberg, he was ‘lucky in misfortune’: in mid-November 1944, Wengler was drafted into the Wehrmacht and survived the war.[16]

Even before that, from the summer of 1944, the Institute had begun to relocate its activities to outposts within Berlin due to increasingly intense air raids. Parts of the library were moved to the outskirts of Berlin. On 3 February 1945, the premises of the International Law Institute in the City Palace were demolished and most of the library and files were destroyed; the rest was placed in the private home of Viktor Bruns.

Bruns was succeeded as KWI director on 1 November 1943 by Carl Bilfinger, professor of public law and international law in Halle from 1924 to 1935, and in Heidelberg from 1935 to 1943. Bilfinger was a controversial figure during the post-war period due to his political involvement in the Third Reich. The result was fierce turbulence in the politics of the past. Bilfinger had to resign from his post at the beginning of July 1946 and was first to be “whitewashed” by a denazification procedure. Karl von Lewinski took over as provisional director of the International Law Institute, which was now affiliated with the German Research University (Deutsche Forschungshochschule) in Berlin.[17] From 18 March 1949 until the beginning of 1954, Bilfinger again led the Institute, now as the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, which took up residence in Heidelberg, Bilfinger’s home town. Democratic lawyers and politicians such as Adolf Grimme considered Bilfinger’s reappointment as director of the International Law Institute a “serious political and substantial mistake” due to his Nazi‑charges. [18] Gerhard Leibholz, who had himself been persecuted by the Nazis, and many others criticised the decision even more harshly. Nevertheless, it was imposed by the Max Planck Society Senate. It was not until Hermann Mosler’s appointment on 29 January 1954 that the institute broke with its Nazi past.

Translation from the German original: Sarah Gebel

[1] On the founding history of the Institute: See Ingo Hueck, Die deutsche Völkerrechtswissenschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Das Berliner Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, das Hamburger Institut für Auswärtige Politik und das Kieler Institut für Internationales Recht, in: Doris Kaufmann (ed.), Geschichte der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im Nationalsozialismus, Bd. 2, Göttingen: Wallstein 2000, 490-527 (499 ff.); Rolf-Ulrich Kunze, Ernst Rabel und das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht 1926-1945, Göttingen: Wallstein 2004, 47 ff.; Rüdiger Hachtmann, Wissenschaftsmanagement im „Dritten Reich“. Geschichte der Generalverwaltung der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, Bd. 1, Göttingen: Wallstein 2007, 110 ff.

[2] Friedrich Glum, Denkschrift über die Notlage der Forschungsinstitute der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, 2 Sepember 1932, BArch,, R 2/12019, Bl. 14, 4.

[3] Quotations by Viktor Bruns from: Nelly Keil, Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft in Gefahr, in: Germania – Zeitung für das Deutsche Volk, 25 December 1932.

[4] AMPG, VI. Abt., Rep. 1, Nr. KWIauslöffRechtuVölkerrecht II/6; Photographer unknown, but presumably a member of the institute.

[5] Hueck (fn. 1), 503.

[6] See Peter Kolmsee, Die Rolle und Funktion der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Wehrpolitik und Wehrwissenschaften bei der Vorbereitung des Zweiten Weltkrieges durch das faschistische Deutschland, unpublished dissertation., University of Leipzig 1966, „Biographischer Anhang der wichtigsten Mitglieder der DGWW”, 3, 14. The list of members reads like a who’s who of the right-wing conservative and early fascist allies of the Nazi movement; On the relations between the DGWW and the general administration of the KWG, which were close for a long time: see Hachtmann (fn. 1), vol. 1, 480-485.

[7] See the corresponding invitation to Glum and the General Administration, MPG Archives, Dept. I, Rep.1A, No. 900/1, sheet 18.

[8] Glum’s file note of 14 Jan. 1937 on a meeting of 9 Jan. with Bruns, MPG Archives, Dept. I, Rep. 1A, No. 2351/4, sheet 180.

[9] AMPG, VI. Abt., Rep. 1, Nr. KWIauslöffRechtuVölkerrecht III/51

[10] Ernst Telschow (ed.), Jahrbuch 1939 der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, Leipzig: Drugulin 1939, 57-85 (citation: 85).

[11] Telschow (fn. 10), 52.

[12] Within the research programme of the MPG Presidential Commission on the History of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society under National Socialism, the Institute was unfortunately not the subject of an independent research project. However, Hueck’s paper (fn. 1) offers important cornerstones for a future project.

[13] Quoted from: Richard Beyler, “Reine Wissenschaft” und personelle Säuberungen. Die Kaiser-Wilhelm-/ Max-Planck-Gesellschaft 1933 und 1945, Berlin: Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science 2004, 30 f.

[14] Hueck (fn. 1), 510.

[15] Hueck (fn. 1), 522.

[16] For details on this affair: Hachtmann (fn. 1), vol. 2, 1147-1156.

[17] Von Lewinski (1873-1951) represented the German Reich at the reparations negotiations in Washington D.C. from 1922 to 1931. He then worked as a lawyer in Berlin until 1945.

[18] Adolf Grimme to Otto Hahn, 14 July 1950, quoted from: Beyler (fn. 13), 33; On further criticism of Bilfinger’s renewed appointment: see Felix Lange, Carl Bilfingers Entnazifizierung und die Entscheidung für Heidelberg. Die Gründungsgeschichte des völkerrechtlichen Max-Planck-Instituts nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, HJIL 74 (2014), 697-731, 721 ff.

|

Suggested Citation: Rüdiger Hachtmann, The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law 1924 to 1945, DOI: 10.17176/20240403-184436-0 |

|

| Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED | |

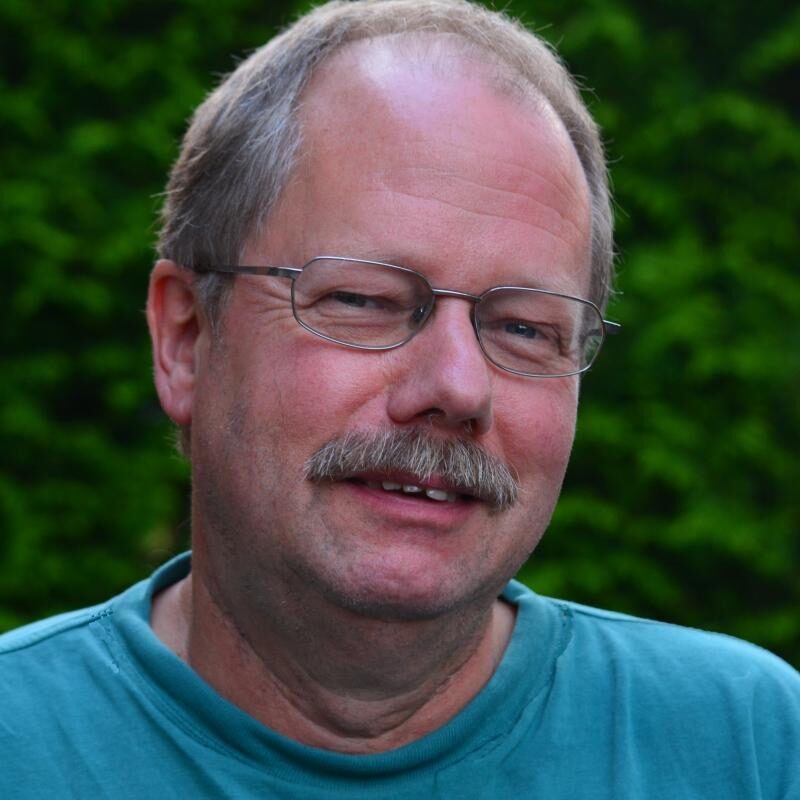

Rüdiger Hachtmann ist Senior Fellow am Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung in Potsdam und apl. Professor an der Technischen Universität Berlin. Forschungsschwerpunkte: Geschichte der NS-Gesellschafts- und Herrschaftsstrukturen sowie der Wissenschaften 1925 bis 1945, der Revolution von 1848/49 und der Rationalisierungsbewegung im 20. Jahrhundert.

Rüdiger Hachtmann is Senior Fellow at the Centre for Contemporary History in Potsdam and Associate Professor at the Technical University of Berlin. Main research interests: History of Nazi social and power structures and the sciences from 1925 to 1945, the revolution of 1848/49 and the rationalisation movement in the 20th century.