Deutsch

Vor 100 Jahren, als das Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht gegründet wurde, verlief zwischen dem Völkerrecht und dem Staatsrecht noch eine scharfe Grenze. Das Völkerrecht regelte die Außenbeziehungen von Staaten, das Verfassungsrecht das Innenverhältnis in Staaten. Überwölbt wurden beide von der Souveränität, die Staaten zugeschrieben wurde und im Kern das Selbstbestimmungsrecht nach außen wie im Inneren meinte. Die äußere Souveränität gab den Staaten einerseits das Recht, ihre Beziehung untereinander frei zu regeln. Andererseits schützte sie die Staaten vor der Einmischung fremder Staaten in ihre inneren Angelegenheiten. Die innere Souveränität bezog sich auf das Recht der Staaten, ihre Herrschafts- und Gesellschaftsordnung frei zu bestimmen, und fand ihren höchsten Ausdruck in der Verfassungsgebung. Beide Seiten der Souveränität hingen insofern zusammen, als die äußere Voraussetzung der inneren ist.

Dementsprechend konnten die Disziplinen des Völkerrechts und des Staatsrechts ein Eigenleben führen. Wo die eine endete, begann die andere. Es war möglich, Völkerrecht zu erforschen und zu lehren, ohne dass man sich im Staatsrecht auskannte, und umgekehrt. Beide waren juristische Disziplinen, aber sie hatten es mit verschiedenen Arten von Recht zu tun. Das Völkerrecht war vertraglich begründetes Recht und ermangelte einer überstaatlichen öffentlichen Gewalt, die es hätte durchsetzen können. Das öffentliche Recht ging aus Gesetzgebung hervor und war mit Sanktionsmöglichkeiten versehen. So verhielt es sich auch noch, als ich 1957 das Jurastudium aufnahm, obwohl damals mit der Gründung der Vereinten Nationen bereits eine grundlegende Änderung der Verhältnisse eingetreten war, die sich aber nicht sofort in einer geänderten Wahrnehmung niederschlug. Ich möchte sogar sagen, dass es sich auch noch so verhielt, als ich 1979 Professor für Öffentliches Recht in Bielefeld wurde. Mein Büro befand sich neben dem von Jochen Frowein, der den Lehrstuhl für Völkerrecht innehatte, bevor er Direktor des Heidelberger Max-Planck-Instituts wurde. Wir pflegten ein gut nachbarliches Verhältnis, aber mit seiner Disziplin hatte ich nichts zu tun.

Die Veränderung, die mit der Gründung der UN einherging, war fundamental, wenngleich sie wegen des bald einsetzenden Ost-West-Gegensatzes, der den Weltsicherheitsrat lähmte, lange Zeit latent blieb. Fundamental war sie gleichwohl, weil die UN sich von älteren internationalen Bündnissen und Allianzen dadurch unterschied, dass ihr von den Staaten Hoheitsrechte abgetreten worden waren, welche sie nun ihnen gegenüber ausüben durfte, notfalls mit militärischer Gewalt, ohne dass die Staaten sich dagegen unter Berufung auf ihre Souveränität wehren konnten. Oberhalb der Staaten gab es nun eine internationale öffentliche Gewalt mit Rechtsetzungsbefugnissen und Durchsetzungsmechanismen, die das nationale Recht auf Dauer nicht unberührt ließ. Die dreihundert Jahre währende Identität von öffentlicher Gewalt und Staatsgewalt war damit zu Ende. Die Grenze zwischen den beiden Rechtsmassen und damit auch zwischen den Disziplinen wurde porös. An Bedeutung steht diese Veränderung der Entstehung des Staates im 16. Jahrhundert und seiner Konstitutionalisierung im 18. Jahrhundert nicht nach.

Völkerrecht

Infolge dieser Entwicklung nahm das Völkerrecht an Bedeutung erheblich zu. Der Bedeutungsgewinn äußerte sich gerade in der Grenzüberschreitung zum nationalen Recht. Die staatliche Souveränität ist seitdem keine absolute mehr, und zwar weder nach außen noch nach innen. Das Mittel des Krieges, ehedem mangels anderer Durchsetzungsmechanismen zur Rechtsverwirklichung statthaft, wurde illegitim. Nur der Verteidigungskrieg ist noch zulässig. Ferner hat sich ein ius cogens ausgebildet, das die Staaten beim Vertragsschluss bindet. Der Einzelne hat eine Rechtsstellung im Völkerrecht gewonnen. Die Staaten sind in der Regelung ihrer inneren Verhältnisse nicht mehr völlig frei. Das humanitäre Völkerrecht zieht ihnen Grenzen. Grundrechte – ihrer Genese in der amerikanischen und der französischen Revolution nach schon immer Menschenrechte – sind es nun auch ihrer Wirkung nach, wenngleich an Effektivität immer noch weit hinter dem staatlichen Grundrechtsschutz zurückbleibend. Humanitäre Interventionen sind im Prinzip anerkannt. Die internationale Gerichtsbarkeit hat einen erheblichen Aufschwung genommen. Weitere supranationale Institutionen sind unter oder neben den UN zustande gekommen. Die wissenschaftliche Disziplin, die diese Entwicklung zum Teil vorgedacht hat, sah sich dadurch wiederum in ihrer Bedeutung beträchtlich gesteigert.

Europäisches Recht

In Europa hat sich diese Entwicklung noch einmal beschleunigt und intensiviert. Sie begann bald nach der Entstehung der UN mit der Gründung des Europarats 1949. In Gestalt der Europäischen Menschenrechtskonvention steht ihm ein rechtliches Instrument zur Verfügung, das einen Mindeststandard an Menschenrechtsschutz in den Mitgliedstaaten garantieren soll und vom Europäischen Gerichtshof für Menschenrechte durchgesetzt werden kann. Die EMRK hält sich im Rahmen des traditionellen Völkerrechts insofern, als sie Entscheidungen des EGMR keine unmittelbare innerstaatliche Wirkung entfalten, also den für konventionswidrig befundenen staatlichen Akt nicht annullieren. Sie überschreiten die Grenzen des traditionellen Völkerrechts aber dadurch, dass Einzelne die Mitgliedstaaten wegen Verletzung von Konventionsrechten verklagen können. Zwar hat der Europarat nicht die Möglichkeit, Urteile zwangsweise durchzusetzen. Er kann aber immerhin den Staaten Geldstrafen auferlegen, wenn sie sich nicht an die Urteile des EGMR halten.

Eine weitere Steigerung entfaltete die Europäische Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft, die in demselben Jahr gegründet wurde, als ich mit dem Jurastudium begann, ohne sich aber im Jurastudium schon auszuwirken. Die EWG, heute EU, übertrifft alle anderen supranationalen Organisationen an Kompetenzfülle und Organisationsdichte und übt die ihr von den Mitgliedstaaten übertragenen öffentlichen Gewalt nicht nur anlassbezogen und punktuell aus wie die UN, sondern permanent und flächendeckend. Seit den grundstürzenden Entscheidungen des Europäischen Gerichtshofs in den Fällen van Gend & Loos und Costa v. ENEL von 1963 und 1964 beansprucht das europäische Recht Vorrang vor dem nationalen Recht. Erst durch die Rechtsprechung des Gerichts ist die EU zu dem geworden, was sie heute ist: ein präzedenzloses Gebilde zwischen einer supranationalen Organisation und einem Bundesstaat, aber näher an diesem als an jener. Der EuGH setzt den Vorrang nicht nur beharrlich durch, sondern erweitert den Anwendungsbereich des Europarechts noch durch eine außerordentlich extensive Interpretation, der nur einige nationale Verfassungsgerichte äußerste Grenzen zu ziehen versuchen.

Nachhaltiger als das Völkerrecht änderte das Europarecht den Gegenstand des öffentlichen Rechts, den Staat und die staatliche Rechtsordnung. Gleichwohl wurde es noch lange ohne Bezug zum Verfassungsrecht, ja zum nationalen Recht überhaupt, behandelt. Anfangs kümmerten sich teils Völkerrechtler, teils Verfassungsrechtler um das neue Rechtsgebiet. Bald schon trat aber eine Spezialisierung des Europarechts ein. Europarechtliche Lehrstühle, Lehrveranstaltungen, Vereinigungen, Zeitschriften und Kongresse entstanden. Eine Eigenart der neuen Disziplin war, dass sich ihre Vertreter überwiegend mit dem politischen Projekt der europäischen Integration identifizierten und daher eine kritische Distanz zum Gegenstand vermissen ließen. Die Europarechtswissenschaft war lange Zeit apologetisch und wurde damit der Funktion von Wissenschaft nicht völlig gerecht.

Staatsrecht

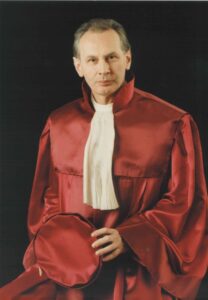

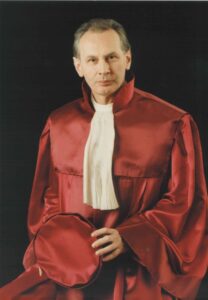

Dieter Grimm als Richter am Bundesverfassungsgericht 1987 [1]

Im Staatsrecht vollzog sich unterdessen eine ambivalente Entwicklung. Der Bedeutungsgewinn des internationalen Rechts macht sich innerstaatlich primär als Bedeutungsverlust der nationalen Verfassungen bemerkbar. Jede Kompetenzabtretung an supranationale Organisationen verkürzt den Anwendungsbereich der nationalen Verfassungen. Sie können ihren Anspruch, die auf dem Territorium des Staates ausgeübte öffentliche Gewalt umfassend zu regeln, nicht mehr einlösen. Der Rechtszustand eines Staates ergibt sich nur noch aus einer Zusammenschau von nationalem und internationalem Recht. Es muss aber betont werden, dass das nicht notwendig gegen die Verfassung gerichtet ist. Das Grundgesetz zum Beispiel war von Anfang an offen für die Anwendung überstaatlichen Rechts in seinem Geltungsbereich. Die Entwicklung darf auch nicht nur unter Verlustgesichtspunkten gesehen werden. Gerade beim Menschenrechtsschutz ist in vielen Staaten, in denen die Grundrechte bis dahin rechtlich keine Rolle spielten, durch den internationalen Menschenrechtsschutz eine erhebliche Verbesserung eingetreten.

Andererseits ist es durch die Ausbreitung der Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit in der zweiten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts zu einer ganz neuen Relevanz der Verfassung für politisches Handeln und gesellschaftliche Verhältnisse gekommen. Ausgangspunkt für Deutschland (und im Gefolge für zahlreiche weitere Staaten) war das Lüth-Urteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichts, erlassen im selben Jahr, in dem die EWG ins Leben trat. Von ihm ist über die Zeit eine Entwicklung ausgegangen, die zu einer Konstitutionalisierung der gesamten nationalen Rechtsordnung geführt hat. Die Disziplin des Staatsrechts, infolge dieser Bedeutungssteigerung der Verfassung fast nur noch als Verfassungsrecht bezeichnet, hatte daran erheblichen Anteil. Entgegen der bekannten These hat das Bundesverfassungsgericht die Staatsrechtslehre nicht „entthront“. Vielmehr konnte das Gericht für bedeutende Urteile auf neue Erkenntnisse der Staatsrechtslehre zurückgreifen.

Die Existenz der Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit hat die Staatsrechtslehre dann aber auch wieder zu immer neuen dogmatischen Verfeinerungen angespornt, so dass heute bereits vor einer Überdogmatisierung gewarnt wird. Allemal ist aber die öffentliche Bedeutung der Staatsrechtslehre durch die überragende Wichtigkeit des Verfassungsgerichts erheblich gestiegen. War die Weimarer Republik mit ihrer ständig gefährdeten Verfassung eine Blütezeit der Verfassungstheorie, so ist die Bundesrepublik mit ihrer fest verwurzelten Verfassung eine Blütezeit der Verfassungsdogmatik. Obwohl die Fortschritte des Völkerrechts und noch weit mehr die Auswirkungen des europäischen Rechts – EMRK wie Unionsrecht – den Gegenstand der Wissenschaft vom öffentlichen Recht, den Staat und das Staatsrecht, nachhaltig verändert haben, hat es lange gedauert, bis die Disziplin die Veränderungen wahrnahm und als relevant für die Behandlung des eigenen Fachs anerkannte.

Rechtsvergleichung

Die zunehmende Verflechtung der Rechtsordnungen, vertikal wie horizontal, hat der Verfassungsvergleichung, ja, dem Vergleich im öffentlichen Recht überhaupt, erheblichen Auftrieb gegeben. Lange Zeit war Rechtsvergleichung keine eigenständige Disziplin. Das heißt nicht, dass es sie nicht gab, sondern nur, dass sie sich noch nicht zu einer Disziplin verdichtet hatten. Rechtsvergleichende Forschungen entsprangen weitgehend der Neigung Einzelner und bezogen sich meist auf wenige favorisierte Länder, oft nur das eigene und ein weiteres. Seit dem neuen Jahrtausend ist die Rechtsvergleichung, gerade im Verfassungsrecht, ein boomendes Feld. Die Gründe liegen zum einen in der Intensivierung der Staatenbeziehungen, zum anderen in der Internationalisierung, die das Bedürfnis nach Kenntnis fremder Rechte erheblich erhöht hat. Hinzu kommt die große Zahl neuer Verfassungen und neuer Verfassungsgerichte gegen Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts, die den Vergleich beflügelt hat.

Mittlerweile kann man an den Universitäten und Forschungseinrichtungen bereits eine Verselbständigung der Rechtsvergleichung beobachten. Vergleichende Lehrveranstaltungen werden heute routinemäßig abgehalten, die Zahl komparatistischer Publikationen, Periodika, Vereinigungen und Kongresse wächst kontinuierlich. Der Verfassungsvergleich wird mit anderen Erkenntnisinteressen und anderen Methoden betrieben als die wissenschaftliche Bearbeitung des positiven Rechts. Beide widmen sich einem normativen Gegenstand. Aber einmal steht die Geltung und richtige Deutung und Anwendung des geltenden Rechts im Vordergrund, das andere Mal die Rechtswirkung und die tatsächliche Praxis. Hier wird die Forschung in normativer, dort in empirischer Absicht betrieben. Dementsprechend dominiert hier die juristische Interpretation, dort die rechtssoziologische Erhebung.

Der Vergleich findet häufig noch verhältnismäßig unambitioniert statt. Es gibt Textvergleiche, Institutionenvergleiche, Rechtsprechungsvergleiche, bisweilen auch Methodenvergleiche, jedoch oft ohne Berücksichtigung des Kontextes, in dem das Recht seine Wirkung entfaltet und von dem die Wirkung abhängt. Diese Art der Rechtsvergleichung ist nicht nutzlos, aber von begrenztem Nutzen. Erst die Einbeziehung der Rechtsverwirklichung vermittelt vertiefte und realitätsnahe Kenntnisse des fremden Rechts und erlaubt Rückschlüsse auf das eigene. Für das eigene Recht kann man bis zu einem gewissen Grad ohne Kontext auskommen, weil das Kontextwissen immer schon mitläuft, oft unausgesprochen oder sogar unbewusst. Für ausländisches Recht muss der Kontext explizit gemacht werden. Das macht die Rechtsvergleichung schwierig, aber auch erst ertragreich.

Ähnlich verhält es sich mit der Theoriegeleitetheit der vergleichenden Forschung. Sie präjudiziert den Blick auf den Gegenstand. Im Rahmen dieses kurzen Vortrags ist nur Zeit, auf zwei Großtheorien einzugehen. Es gibt Rechtsvergleichung auf der Grundlage der Annahme, dass das öffentliche Recht (wie Recht überhaupt) eine relative Autonomie genießt und rechtliche Operationen einer spezifisch juristischen Logik folgen. Für andere ist das ein realitätsblinder Idealismus. Verfassungen sind dann nicht zur Legitimation und Limitation von Herrschaft da, sondern erweisen sich als hegemoniale Projekte zur Machtsicherung über die Zeit. Rechtsprechung ist für diese sich als realistisch verstehende Forschungsrichtung ein Vorgang, der anderen als juristischen Kriterien folgt, weil Richter wie politische oder wirtschaftliche Akteure Nutzenmaximierer sind und anderweitig gefundene Ergebnisse nur nachträglich als rechtlich zwingend ausgeben. Dogmatik und Methode erscheinen dann als Berufsideologie. Sie verdienen keine wissenschaftliche Beachtung. Das erklärt das Desinteresse vieler Rechtsvergleicher am Vorgang der Auslegung und Anwendung des Rechts. In den USA ist diese Sicht weit verbreitet, in Europa hat sie bisher nicht die Oberhand gewonnen.

Das MPI

Wenn ich mich zum Schluss der Frage zuwende, wie sich diese Entwicklung in dem Max-Planck-Institut widerspiegelt, so handelt es sich zum einen um Eindrücke, die keiner eigenen Forschung entspringen, zum anderen um Informationen, die ich den Forschungen von Felix Lange entnehme. Danach dominierte in der Zeit von der Gründung des Instituts bis zum Kriegsende das Völkerrecht. Das entsprach den Gründungsmotiven des Instituts, den völkerrechtlichen Standpunkt des Deutschen Reichs in der vom Versailler Vertrag geprägten Nachkriegszeit zu stärken. Auch nach der Wiedergründung im Jahr der Entstehung der Bundesrepublik blieb es trotz der veränderten Bedingungen zunächst bei der Priorisierung des Völkerrechts. Offenkundig war der Praxisbezug der Forschung. Dem entsprach die Methode. Im Unterschied zu einer eher philosophisch-historischen Annäherung an den Gegenstand, der anderwärts vorherrschte, war sie juristisch. Neuere Fragestellungen und Theorieansätze hatten lange keine Chance.

Die Wirkung des Instituts war freilich groß. Allenthalben traf man auf den völkerrechtlichen Lehrstühlen in Deutschland Habilitanden aus dem MPI an. Für den europäischen Menschenrechtsschutz war das MPI besonders wichtig, weil zwei seiner Direktoren Richter am EGMR waren, Hermann Mosler von 1959 bis 1981, Rudolf Bernhardt von 1981 bis 1998, zuletzt sogar Präsident. Ein weiterer Direktor, Jochen A. Frowein, gehörte von 1973 bis 1993 der Europäischen Kommission für Menschenrechte an, die dem Gerichtshof bis zu der Reform von 1999 vorgeschaltet war. Georg Ress, der von 1998 bis 2004 als EGMR-Richter amtierte und zuvor schon Mitglied der Kommission gewesen war, war aus dem MPI hervorgegangen.

Für das deutsche Staatsrecht war das Institut nicht zuständig, wohl aber von Beginn an für das ausländische öffentliche Recht. Gleichwohl trat der Vergleich erst seit Ende der fünfziger Jahre stärker in Erscheinung, insbesondere durch breit angelegte vergleichende Kolloquien, die ihren bleibenden Niederschlag in zum Teil umfangreichen Publikationen fanden. Viele machen aber den Eindruck einer eher additiven als integrativen Vergleichung. Stark war das Institut jedoch, was die Vorhaltung von Expertise über das öffentliche Recht fremder Staaten betraf. Diese Expertise war aber nicht in sich rechtsvergleichend. Insofern bildete das Jahr 2002 eine Zäsur in der Institutsgeschichte. Erstmals wurde ein Direktor berufen, dessen Interessenschwerpunkt nicht das Völkerrecht war, sondern das Europarecht und die Rechtsvergleichung im öffentlichen Recht, und zwar mit erkennbar theoretischen Ambitionen, die vor allem der Erklärung des öffentlichen Rechts unter Bedingungen der Internationalisierung und Globalisierung galten. Der internationale Einfluss des MPI ist damit abermals gestiegen.

[1] Foto: Dieter Grimm.

|

Suggested Citation: Dieter Grimm, 100 Jahre Öffentliches Recht. Die Entwicklung der Disziplin und das MPI, MPIL100.de, DOI: 10.17176/20240403-102642-0 |

|

| Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED | |

English

100 years ago, when the Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law was founded, a sharp boundary divided international law and constitutional law. International law regulated the external relations among states, constitutional law the internal relations within states. However, both shared the notion of sovereignty, which was ascribed to states and in essence referred to the right to self-determination both externally and internally. External sovereignty gave states the right to freely regulate their relations with each other, on the one hand. On the other hand, it protected them from interference in their internal affairs by foreign states. Internal sovereignty referred to the right of states to freely determine their system of governance and social order and found its highest manifestation in the act of constitution-making. Both sides of sovereignty were related insofar as external sovereignty is a prerequisite for internal sovereignty.

Consequently, the disciplines of international law and constitutional law could exist independently of each other. Where one ended, the other began. It was possible to research and teach international law without being familiar with constitutional law, and vice versa. Both were legal disciplines, but they dealt with different types of law. International law was based on treaties and lacked a supranational public authority that could have enforced it. Public law emerged from legislation and was characterised by the possibility of sanctions. This was still the case when I started studying law in 1957, even though a fundamental change in circumstances had already occurred with the founding of the United Nations, which, however, was not immediately reflected in a changed perception. I might even go so far as to say that this was still the case when I became Professor of Public Law in Bielefeld in 1979. My office neighboured that of Jochen Frowein, who held the Chair of Public International Law before becoming Director of the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg. We had a good neighbourly relationship, but I had nothing to do with his field.

The transformation that was brought forth by the founding of the UN was fundamental, even if it remained latent for a prolonged period of time due to the onset of the East-West conflict, which paralysed the UN Security Council. Nevertheless, it was a fundamental change because the UN differed from older international associations and alliances in that states had transferred sovereign rights to it, which it was now authorised to exert on them, if necessary by using military force, without the states being able to defend themselves by invoking their sovereignty. Above the states, there existed now an international public authority with legislative powers and enforcement mechanisms that in the long term would not leave national law untouched. The three-hundred-year-old identity of public authority and state authority had thus come to an end. The boundary between the two bodies of law and consequently between the disciplines became porous. In terms of significance, this change equals the emergence of the state in the 16th century and its constitutionalisation in the 18th century.

International Law

As a result of this development, the importance of international law increased considerably. The increase manifested itself particularly in the transgression of the border with national law. Since then, state sovereignty is no longer absolute, both internally and externally. War, formerly permissible due to the lack of other enforcement mechanisms for the realisation of law, became illegitimate. It remains permissible only for purposes of self-defense. Furthermore, a jus cogens has developed, which binds states when concluding treaties. The individual has gained a legal status in international law. States are no longer completely free to regulate their internal relations. International humanitarian law imposes limits on them. Fundamental rights – in the American and French revolutions already perceived as human rights – are now human rights also in terms of their impact, even if their effectiveness still lags far behind the protection of fundamental rights by the state. Humanitarian interventions are in principle recognised. International jurisdiction has seen a considerable upswing. Other supranational institutions have come into being under or alongside the UN. The academic discipline, which in part anticipated this development, has in turn seen its importance increased considerably.

European Law

In Europe, this development has once again accelerated and intensified. It began soon after the emergence of the UN with the founding of the Council of Europe in 1949. In the form of the European Convention on Human Rights, it has a legal instrument at its disposal that is intended to guarantee a minimum standard of human rights protection in the member states and can be enforced by the European Court of Human Rights. The ECHR remains within the framework of traditional international law insofar as decisions of the ECtHR do not have direct domestic effect, i.e. they do not annul state acts found to be contrary to the Convention. However, they exceed the limits of traditional international law in that individuals can sue member states for violations of convention rights. The Council of Europe does not have the power to enforce judgements. However, it can impose fines on states if they do not comply with the judgements of the ECtHR.

The European Economic Community, which was founded in the same year that I started studying law, was another step forward, although it had no impact on my law studies. The EEC, now the EU, surpasses all other supranational organisations in terms of powers and organisational density, and exercises the public authority delegated to it by the member states not only on an ad hoc and selective basis like the UN, but permanently and comprehensively. Since the landmark decisions of the European Court of Justice in the van Gend & Loos and Costa v. ENEL cases of 1963 and 1964, European law claims precedence over national law. It is only through the jurisprudence of the Court that the EU has become what it is today: an unprecedented entity between a supranational organisation and a federal state, but closer to the latter than to the former. The ECJ not only persistently enforces primacy, but also extends the scope of application of European law by means of an extraordinarily extensive interpretation, which only some national constitutional courts attempt to draw ultimate limits to.

European law changed the object of public law, the state, and the national legal order, more permanently than international law. Nevertheless, for a long time it was treated without reference to constitutional law, or indeed to national law in general. Initially, the new area of law was dealt with partly by international law experts and partly by constitutional law experts. Soon, however, the treatment of European law became a matter for specialists. Chairs, courses, associations, journals, and congresses on European law were established. One peculiarity of the new discipline was that its members predominantly identified with the political project of European integration and therefore lacked a critical distance to the subject matter. For a long time, the discipline of European law was apologetic and thus did not fully fulfil its scholarly function.

Constitutional Law

Dieter Grimm as Federal Constitutional Court judge, 1987 [1]

Meanwhile, an ambivalent development has taken place in constitutional law. The growing importance of international law entails a loss of importance of national constitutions. Every transfer of competences to supranational organisations reduces the scope of application of national constitutions. They can no longer fulfil their claim to comprehensively regulate the public authority exercised on the territory of the state. The law of the land can only be ascertained by way of a synopsis of national and international law. However, it must be emphasised that this is not necessarily directed against the constitution. German Basic Law, for example, has always been open to the application of supranational law within its area of application. The development should not only be seen from a perspective of loss. International human rights protection, for instance, has led to a considerable improvement in the protection of human rights in many states where fundamental rights had previously played no legal role.

On the other hand, the spread of constitutional jurisdiction in the second half of the 20th century led to a completely new relevance of the constitution for political action and social relations. The starting point for Germany (and subsequently for numerous other countries) was the Lüth judgement of the Federal Constitutional Court, issued in the same year in which the EEC came into being. Over the course of time, it has resulted in the constitutionalisation of the entire national legal system. The discipline of “Staatsrecht”, almost exclusively referred to as constitutional law as a consequence of this increase in the importance of the constitution, played a significant role in this. Contrary to a well-known thesis, the Federal Constitutional Court has not “dethroned” the discipline of “Staatsrecht”. On the contrary, the Court was able to draw on new insights from constitutional law theory for important judgements.

The existence of constitutional jurisdiction has, however, spurred constitutional law doctrine on to ever new dogmatic refinements, so that today there are already warnings of an over-dogmatisation. Nevertheless, the public significance of the discipline has increased considerably due to the paramount importance of the Constitutional Court. While the Weimar Republic, with its constantly jeopardised constitution, was a high point of constitutional theory, the Federal Republic, with its firmly rooted constitution, is a high point of constitutional dogmatics. Although the progress of international law and even more so the effects of European law – the ECHR and Union law – have permanently changed the subject of the study of public law, the state and its law, it took a long time for the discipline to recognise the changes and acknowledge them as relevant for the study of its own subject.

Comparative Law

The increasing interdependence of legal systems, both vertically and horizontally, has given comparative constitutional law, and indeed comparative public law in general, a considerable impetus. For a long time, comparative law was not an independent discipline. This does not mean that it did not exist, but merely that it had not yet crystallised into a discipline. Comparative legal research was largely the result of the inclination of individuals and usually related to a few favoured countries, often just one’s own and one further country. Since the new millennium, comparative law has been a booming field, especially in constitutional law. The reasons for this lie on the one hand in the intensification of state relations and on the other in internationalisation, which has considerably increased the need for an understanding of foreign law. Added to this is the large number of new constitutions and new constitutional courts towards the end of the 20th century, which has fuelled comparative law.

Nowadays, one can observe a growing independence of comparative law at universities and research institutions. Comparative courses are now routinely taught, and the number of comparative publications, periodicals, associations, and conferences continues to grow. Constitutional comparison is pursued with different epistemological interests and methods than the academic study of positive law. Both are dedicated to a normative subject. Yet on the one hand, the focus is on the validity and correct interpretation and application of the law in force, and on the other hand on the legal effect and actual practice. In the former, research is conducted with normative intent, in the latter with empirical intent. Accordingly, the legal interpretation dominates in one case, and the legal-sociological analysis in the other.

Comparisons are often still relatively unambitious. There are text comparisons, comparisons of institutions, comparisons of case law, sometimes even comparisons of methods, but often without taking into account the context in which the law unfolds its effect and on what the effect depends. This type of legal comparison is not useless, but it is of limited use. Only the inclusion of the actual application of the law provides in-depth and realistic insights into foreign law and allows conclusions to be drawn about one’s own law. For one’s own law, one may get along to a certain extent without regard to the context, because the contextual knowledge always runs in parallel, often unspoken or even unconsciously. For foreign law, the context must be made explicit. This makes comparative law difficult, but it also makes it rewarding.

A similar situation applies to the theory-led nature of comparative research. It prejudices the view of the object. In the context of this short presentation, there is only time to discuss two major theories. There is comparative law based on the assumption that public law (like law in general) enjoys relative autonomy and that legal operations follow a specific legal logic. For others, this is reality-blind idealism. Constitutions are not there for the legitimisation and limitation of rule, but rather serve as hegemonic projects for securing power over time. For this research direction, which sees itself as realistic, jurisprudence is a process that follows criteria deviating from legal standards, because judges, like political or economic actors, are utility maximisers and only retrospectively present their results as if derived with necessity from the law. Doctrine and method therefore appear as professional ideology. They do not deserve academic attention. This explains the lack of interest shown by many comparative lawyers in the process of interpreting and applying the law. Although this perspective is widespread in the USA, it has not yet gained prevalence in Europe.

The MPIL

When I finally turn to the question of how this development is reflected in the Max Planck Institute, I rely on the one hand on impressions that are not based on my own research, and on the other hand on information that I have gathered from Felix Lange’s research. According to this, international law dominated the period between the founding of the Institute and the end of the war. This was in line with the Institute’s founding motives of strengthening the German Reich’s position on international law in the post-war period, which was characterised by the Treaty of Versailles. Even after its re-establishment in the year the Federal Republic of Germany was founded, international law was initially prioritised despite the changed conditions. The practical relevance of the research was obvious. The methods corresponded with this. In contrast to a more philosophical-historical approach to the subject matter, which prevailed elsewhere, the approach was of a legal nature. For a long time, newer questions and theoretical approaches had no real prospect.

The impact of the Institute was, however, considerable. You could find habilitation graduates from the MPI in international law departments all over Germany. The MPI was particularly important for the protection of European human rights because two of its directors were judges at the ECHR, Hermann Mosler from 1959 to 1981 and Rudolf Bernhardt from 1981 to 1998, who eventually became its president. Another director, Jochen A. Frowein, was a member of the European Commission of Human Rights from 1973 to 1993, which operated as first instance until the reform of 1999. Georg Ress, who served as an ECtHR judge from 1998 to 2004 and had previously been a member of the Commission, had also emerged from the MPI.

The Institute did not cover German constitutional law, but it did cover foreign public law from the very beginning. Nevertheless, it was only from the end of the 1950s onwards that comparative law became more prominent, particularly through broad-based comparative colloquia, some of which were documented in extensive publications. Many, however, give the impression of an additive rather than integrative comparison. Nevertheless, the Institute was particularly influential when it came to providing expertise on the public law of foreign states. However, this expertise was not inherently comparative. In this respect, 2002 marked a turning point in the Institute’s history. For the first time, a director was appointed whose focus of interest was not international law, but rather European law and comparative public law, with recognisable theoretical ambitions that were primarily aimed at explaining public law under conditions of internationalisation and globalisation. As a result, the international influence of the MPI increased once again.

Translation from the German original: Áine Fellenz

[1] Photo: Dieter Grimm.

|

Suggested Citation: Dieter Grimm, 100 Years of Public Law. The Development of the Discipline and of the MPI, MPIL100.de, DOI: 10.17176/20240403-102716-0 |

|

| Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED | |

Dieter Grimm ist em. Professor für Öffentliches Recht an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Grimm wurde 1979 Professor für Öffentliches Recht an der Universität Bielefeld und war von 1987 bis 1999 Richter des Bundesverfassungsgerichts. Nach seinem Ausscheiden aus dem Gericht lehrte er in Berlin und Yale. 2001 bis 2007 war er außerdem Rektor des Wissenschaftskollegs zu Berlin.

Dieter Grimm is Professor Emeritus of Public Law at the Humboldt University of Berlin. Grimm became Professor of Public Law at the University of Bielefeld in 1979 and was a judge at the Federal Constitutional Court from 1987 to 1999. After leaving the court, he taught in Berlin and Yale. From 2001 to 2007, he was also Rector of the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin.