Deutsch

Personeller und intellektueller Input von KWI und MPI im Friedenspalast von Den Haag

Wie Jan Klabbers in seinem Blogbeitrag[1] zutreffend bemerkt hat, kann sowohl das Kaiser‑Wilhelm‑Institut (KWI) als auch das Max‑Planck‑Institut (MPI) für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht als Schmiede für die Besetzung hochrangiger völkerrechtsrelevanter Posten im internationalen und nationalen Bereich angesehen werden. Daher ist es nicht überraschend, dass sich auch unter den Richtern internationaler Gerichte seit jeher zahlreiche Personen finden, die aus dem Institut hervorgegangen sind.

In diesem Beitrag soll dies mit Blick auf den Internationalen Gerichtshof (IGH) in Den Haag und seinen Vorgänger, den Ständigen Internationalen Gerichtshof (StIGH), gezeigt werden. Die Wechselbeziehung zwischen diesen Institutionen ist einerseits deswegen im Rahmen der 100‑Jahrfeier interessant, weil beide aus etwa derselben Zeit stammen und auf das damals noch im Dornröschenschlaf liegende Völkerrecht fokussiert sind, zum anderen, weil meine eigene Tätigkeit am Institut immer auch auf diesen Bereich konzentriert war (dazu unten mehr). Dabei ist der erste Ansatz natürlich die Frage danach, ob deutsche Richter in diesen Institutionen aus dem KWI/MPI kamen (I.). An zweiter Stelle ist von großer Bedeutung dann aber auch die Beteiligung deutscher Völkerrechtler als Verfahrensvertreter in streitigen Fällen und Gutachten vor dem StIGH und IGH. Dieser Aspekt ist natürlich deutlich schwieriger zu beleuchten und kann hier nur exemplarisch dargestellt werden, da eine detaillierte Untersuchung den Charakter des Blogs sprengen würde (II.). An dritter Stelle soll noch kurz ein Blick auch auf den „wissenschaftlichen Input“ des Instituts zum StIGH und IGH geworfen werden (III.).

I. Deutsche Juristen als Richter am StIGH und IGH

Sowohl der StIGH als auch der IGH bestanden beziehungsweise bestehen bekanntlich aus 15 permanenten Richtern, die für jeweils neun Jahre gewählt werden und die alle über eine unterschiedliche Staatsangehörigkeit verfügen müssen. Hinzukommen können noch ad hoc Richter, die von Streitparteien, die keinen Richter ihrer Nationalität auf der Richterbank haben (Art. 31 IGH-Statut), für die Zwecke dieses Streitfalls ernannt werden können. Zudem können alle Mitgliedstaaten des Gerichts in Gutachtenverfahren ihre Stellungnahme zur vorgelegten Rechtsfrage abgeben (Art. 66 IGH-Statut).

Walther Schücking (links) und Viktor Bruns in Den Haag, undatiert[2]

Angesichts der Tatsache, dass die Vereinten Nationen mittlerweile 193 Mitgliedstaaten haben und der Gerichtshof „eine Vertretung der großen Kulturkreise und der hauptsächlichen Rechtssysteme der Welt gewährleisten“ soll, kommt der Wahl der Richter entscheidende Bedeutung zu. Ohne hier in die Details zu gehen, die in Art. 2-19 des Statuts geregelt sind, ist zu klären, unter welchen Voraussetzungen deutsche Juristen Richter im Gerichtshof werden können. Dabei ist vor allem die Frage nach dem Zustandekommen der Kandidatenlisten von Interesse. Die auf den ersten Blick naheliegende Lösung, dass die Staaten Kandidaten benennen, ist mit guten Gründen nicht übernommen worden. Ausschlaggebend war, dass die Liste der Kandidaten soweit wie möglich unabhängig von politischen Einflussnahmen sein soll. Das führte zu der Regelung, dass die Richterkandidaten aus einer in einem komplizierten Verfahren aufgestellten Liste von Personen vorgeschlagen werden; diese wird von den jeweiligen nationalen Gruppen des Ständigen Schiedshofs erstellt.[3] Die Wahl erfolgt durch den Sicherheitsrat und die Generalversammlung gleichzeitig in getrennten Wahlgängen (ohne Vetorecht im Sicherheitsrat), wobei alle drei Jahre ein Drittel der Richter gewählt wird.[4] Eine Wiederwahl ist zulässig. Auch wenn dies nirgends ausdrücklich vorgesehen ist, hat jedes ständige Mitglied im Sicherheitsrat traditionell einen Richter im Gerichtshof.[5] Die restlichen zehn Richter werden auf der Grundlage von Quoten gewählt, die den einzelnen Regionalen Gruppen, die seit 1963 im Rahmen der VN bestehen, zugeteilt sind. Seit 2017 sieht die Verteilung unter Einschluss der Richter mit Staatsangehörigkeit eines ständigen Mitglieds des Sicherheitsrats folgendermaßen aus: Westeuropa und andere Staaten (WEOC) wird durch vier Richter vertreten, Osteuropa durch zwei Richter, Lateinamerika ebenfalls durch zwei Richter, Asien durch vier Richter und Afrika schließlich durch drei Richter. Da zur WEOC auch die Vereinigten Staaten zählen, bleibt für diese Gruppe nur eine Richterstelle, die „frei“ besetzt werden kann, da grundsätzlich drei der Posten durch Staatsangehörige eines ständigen Mitglieds des Sicherheitsrats vorgegeben sind: die USA, Frankreich und Großbritannien. Allerdings ist das Vereinigte Königreich 2017 erstmals mit einer Kandidatur gescheitert, so dass derzeit die USA und Frankreich einen Richterposten besetzen und die übrigen beiden WEOC-Positionen von Australien (Charlesworth) und Deutschland (Nolte) besetzt sind.

Der StIGH, der 1922 gegründet wurde und das erste internationale ständige Gericht überhaupt war, datiert vor der Gründung des KWI und hatte im Laufe seines Bestehens nur einen Richter deutscher Nationalität; das war Walther Schücking, der damalige Direktor des Kieler Instituts für Völkerrecht, des heutigen Walther‑Schücking‑Instituts. Seit 1921 stand er auf der Liste der möglichen ad hoc Richter und 1931 wurde er zum Richter berufen. Allerdings konnte er seine Amtszeit nicht ausschöpfen, da er schon 1935 verstarb. Seine Richterstelle wurde nicht wieder durch einen deutschen Juristen gefüllt, nachdem das Deutsche Reich im Jahr 1933 nicht nur aus dem Völkerbund ausgetreten war, sondern auch das Statut des StIGH gekündigt hatte.[6]

Als ad hoc Richter wirkten drei Deutsche in Verfahren vor dem StIGH mit: Viktor Bruns,[7] Ernst Rabel,[8] und der bereits erwähnte Walther Schücking.[9] Aus dem KWI war Viktor Bruns somit der erste deutsche Jurist, der am StIGH als Richter, genauer als ad hoc Richter, eingebunden war.

Am IGH gab/gibt es bisher vier deutsche Richter: Hermann Mosler (1976 bis 1985), Carl-August Fleischhauer (1994 bis 2003), Bruno Simma (2003 bis 2012) sowie Georg Nolte (seit 2021). Bei Hermann Mosler führte der Weg zum Richteramt über die Funktion als ad hoc Richter im Fall North Sea Continental Shelf.[10] Auch Carl-August Fleischhauer und Bruno Simma haben als ad hoc Richter vor dem IGH gewirkt, allerdings erst nach Beendigung ihres Amts als Richter. Fleischhauer, dessen Amtszeit am IGH 2003 geendet hatte, wurde direkt im Anschluss als deutscher ad hoc Richter im Fall Certain Property ernannt, der seit 2001 vor dem Gericht anhängig war.[11] Zwar war zu dieser Zeit, 2003, Bruno Simma als deutscher Richter im Gericht tätig, da er aber bereits zuvor als Mitglied des völkerrechtlichen Beirats des Auswärtigen Amtes mit der zugrundeliegenden Rechtsfrage befasst gewesen war, trat er nach Art. 17 Abs. 2 IGH-Statut von der Teilnahme an diesem Fall zurück. Bruno Simma war jedoch später als von Costa Rica nominierter ad hoc Richter im Fall Maritime Delimitation in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean tätig.[12] Außerdem wirkte er als von Chile benannter ad hoc Richter im Fall Dispute over the Status and Use of the Waters of the Silala[13], sowie für Costa Rica im Fall Land Boundary in the Northern Part of the Isla Portillo[14] mit.

Zu den genannten drei Personen, die, teils vor (so Hermann Mosler), teils nach ihrer Amtszeit, als Richter auch als ad hoc Richter wirkten, ist als einziger weiterer ad hoc Richter deutscher Nationalität Rüdiger Wolfrum, ehemaliger Direktor am MPI, aufgetreten, der nicht am IGH, aber am Internationalen Seegerichtshof als Richter tätig war. Vor dem IGH ist er momentan in zwei Fällen als ad hoc Richter tätig.[15]

Bis auf Bruno Simma, der zwar zu keiner Zeit offizieller Mitarbeiter am Institut, diesem jedoch stets eng verbunden war,[16] gingen alle genannten Richter aus dem MPI hervor. Hermann Mosler war, als er zum Richter gewählt wurde, Direktor des Instituts. Carl‑August Fleischhauer war nach seinem zweiten Juristischen Staatsexamen ab 1960 Referent am Institut, wo er unter Hermann Mosler seine Dissertation schrieb. 1961 promovierte er dann an der Heidelberger Universität.[17] Kurz darauf beendete er seine Zeit am Institut bereits wieder und begann ab 1962 eine beeindruckende Karriere im Auswärtigen Amt, bevor er später stellvertretender Generalsekretär der Vereinten Nationen und deren Rechtsberater wurde. Dem Institut blieb er jedoch durch seine Mitgliedschaft im Kuratorium von 1975‑2002 verbunden.

Georg Nolte, dessen Amtszeit als Richter am IGH im Jahr 2021 begann, war in seiner wissenschaftlichen Laufbahn dem MPI sehr eng verbunden und ist es weiterhin durch seine Tätigkeit im Kuratorium des Instituts. Von 1984 bis 1990 war er neben der juristischen Referendarzeit als Doktorand wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter und von 1992-1999 Referent am MPI. 1991 promovierte er unter seinem akademischen Lehrer Jochen Abr. Frowein, seinerzeit Direktor am Institut, [18] und 1998 habilitierte er sich, ebenfalls bei Frowein.[19]

Sieht man sich diese Bilanz an und stellt sie in Zusammenhang zu der Tatsache, dass jeweils nur ein Richter am IGH aus Europa neben den Staatsangehörigen der Vetomächte USA und Frankreich (und bis 2017 Großbritannien) dem Gerichtshof angehören kann, so ist auch hier ein starker Einfluss des MPI als Wegbereiter für höchste Karrieren nicht zu verkennen.

II. Institutsmitarbeiter als Parteivertreter in Verfahren vor dem Gerichtshof

Wie in nationalen Verfahren, werden auch vor internationalen Gerichten die Parteien durch „Anwälte“ vertreten, wobei es keine der Zulassung von Anwälten im nationalen Recht vergleichbare Voraussetzung gibt. Art. 42 des Statuts legt nur fest, dass Staaten durch „agents“ vertreten werden (das sind die „Ansprechpartner“ des IGH; im konkreten Fall und aus praktischen Gründen handelt es sich in der Regel um die diplomatischen oder konsularischen Vertreter in Den Haag). Diese können – und das geschieht auch regelmäßig – durch „counsels or advocates“ unterstützt werden, die anwaltlich die Belange der Parteien in Form der Ausarbeitung der Schriftsätze und der Plädoyers in der mündlichen Verhandlung vertreten. Weder im Statut noch in der Verfahrensordnung wird Näheres zur erforderlichen Qualifikation dieser Personen vorgegeben. Man geht von der allgemeinen Erwartung aus, dass Staaten nur „entsprechend qualifizierte Personen“ bestellen werden, was natürlich in ihrem eigenen Interesse liegt und daher in der Praxis grundsätzlich auch erfolgt ist. Und hier kommen dann wieder das KWI und das MPI in den Blick, mit ihrem besonderen Fokus auf das Völkerrecht, das immer Gegenstand der Fälle vor dem Internationalen Gerichtshof ist.

Aus dem KWI, dessen Gründung in die Anfangsjahre des StIGH fällt, war nur Viktor Bruns, der, wie oben erwähnt, in mehreren Fällen vor dem StIGH als ad hoc Richter fungierte, auch als Vertreter Deutschlands in zwei Fällen eingesetzt.[20]

Viktor Bruns (links) als Prozessvertreter, undatiert.[21]

Aus den Informationen über andere Mitarbeiter des KWI lässt sich nur für Carlo Schmid und Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg ein Hinweis auf eine Beteiligung in Verfahren vor dem StIGH entnehmen. Beide wurden in den zwei genannten Fällen von Bruns in dessen Vertretung des Deutschen Reichs vor dem Gericht einbezogen.[22] Erich Kaufmann, der von 1927 bis 1934 als wissenschaftlicher Berater des KWI fungierte,[23] und sein Assistent Friedrich Berber,[24] waren auch als Parteivertreter vor dem StIGH tätig, waren aber nicht als Mitarbeiter aus dem Institut hervorgegangen.

Vor dem IGH waren und sind Juristen (ehemalige und aktuelle) aus dem MPI in weit größerem Maße als counsel, und zwar nicht nur für Deutschland, vertreten. So ist Professor Frowein im Fall „Liechtenstein gegen Deutschland“ für die Bundesregierung tätig geworden und im Fall „Kamerun gegen Nigeria“ war er eingebunden, hat jedoch sein Mandat vor Beendigung des Verfahrens niedergelegt; im Gutachten zur Unabhängigkeit des Kosovo hat er die Rechtsauffassung Albaniens vorgetragen. Die jetzige Direktorin Anne Peters war Teil des deutschen Teams zur Vertretung der deutschen Rechtsauffassung im Fall „Nicaragua gegen Deutschland“,[25] in dem bisher erst eine einstweilige Anordnung ergangen ist, so dass sie weiter im Verfahren eingebunden ist.

Agents der deutschen Seite im Verfahren „Nicaragua gegen Deutschland“ (v.l.n.r.): Paolo Palchetti, Samuel Wordsworth, Anne Peters, Christian J. Tams[26]

Von den ehemaligen Mitarbeitern wurde Michael Bothe 2003/2004 zur Vertretung der Rechtsansichten der Arabischen Liga im Gutachten zum Bau der israelischen Sperranlagen im besetzten palästinensischen Gebiet herangezogen[27] und Christian Tomuschat hat Deutschland im Immunitätsstreit zwischen Italien und Deutschland vertreten[28]. Ein ehemaliger Mitarbeiter des Instituts beeindruckt in diesem Zusammenhang ganz besonders, da er in 16 Fällen als Vertreter einer Partei tätig war, beziehungsweise noch ist, und somit als Teil der bar angesehen wird, der „ständigen Anwaltschaft“ vor dem IGH, von der man oft spricht, obwohl es sie offiziell nicht gibt: Andreas Zimmermann. Es würde zu weit führen, hier alle Fälle zu nennen und mag daher genügen, auf die noch anhängigen Fälle und erst kürzlich abgeschlossenen Verfahren hinzuweisen: das laufende „Gutachten zum Klimawandel“, den (zweiten) „Immunitätsfall Italien v. Deutschland“ und das Streitverfahren „Guyana gegen Venezuela“ (bei dem, wie erwähnt, Rüdiger Wolfrum der von Guyana benannte ad hoc Richter ist; beide noch anhängig), sowie das kürzlich abgeschlossene Gutachtenverfahren zum Rechtsstatus des besetzten palästinensischen Gebiets.[29]

Imposant: Die Eröffnung der Verhandlung im Fall „Bahrain, Ägypten, Saudi-Arabien und Vereinigte Arabische Emirate gegen Katar“, 2019[30]

Jeder dieser counsel hat zum Teil andere Mitarbeiter des Instituts (oder seines Lehrstuhls) bei der Ausarbeitung der Schriftsätze und der Vorbereitung der mündlichen Verhandlung miteingebunden und bisweilen sogar zu den Verhandlungen mit nach Den Haag genommen, was für die Betroffenen natürlich jeweils ein absolutes Highlight war. Aus eigener Erfahrung[31] kann ich sagen, dass die Teilnahme an einem Fall in den imposanten Räumlichkeiten des Friedenspalasts in Den Haag ein unvergessliches Erlebnis darstellt. Zudem beeindruckt insbesondere auch das konkrete Vorgehen: So wird, zum Beispiel, größter Wert auf die Verhinderung jedes Kontakts der Parteien und ihrer Vertreter mit den Richtern und den Parteivertretern der Gegenseite gelegt, was einige Vorkehrungen für den Aufenthalt, etwa bezüglich Kaffeepausen, Zuteilung von Arbeitsräumen und Ähnlichem, mit sich bringt. Außerdem wird umfassender Einsatz verlangt, da nach dem mündlichen Vortrag der Gegenpartei oder auch auf Fragen der Richter nach dem eigenen Plädoyer in der Regel nur die Abend- und Nachtstunden zur angemessenen Vorbereitung der Reaktion verfügbar sind.

III. Wissenschaftlicher Input für die Arbeit des Gerichtshofs

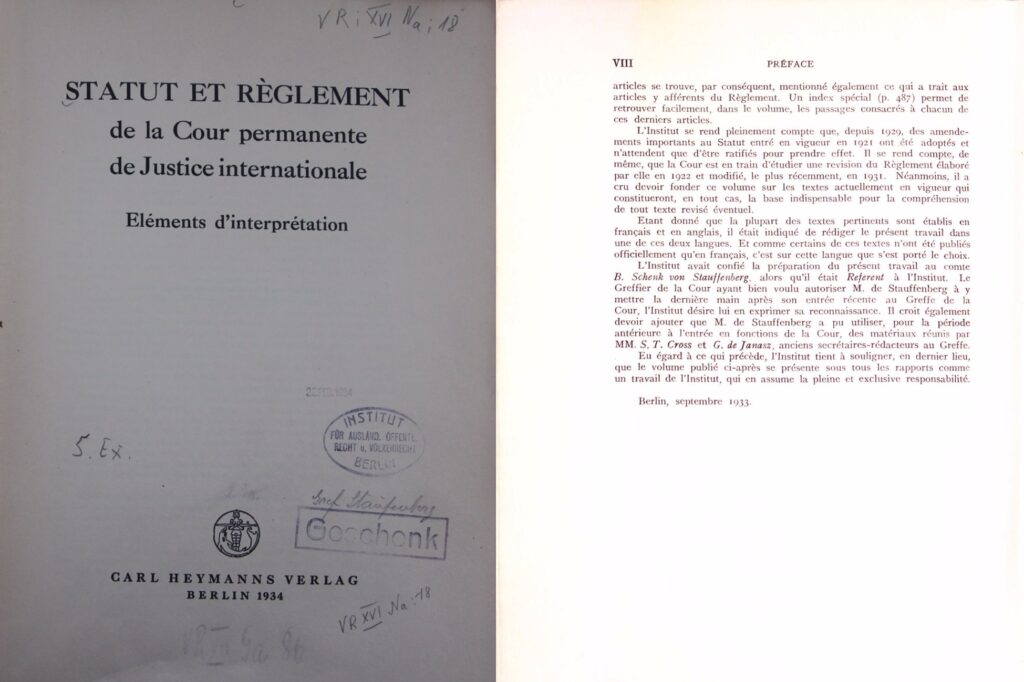

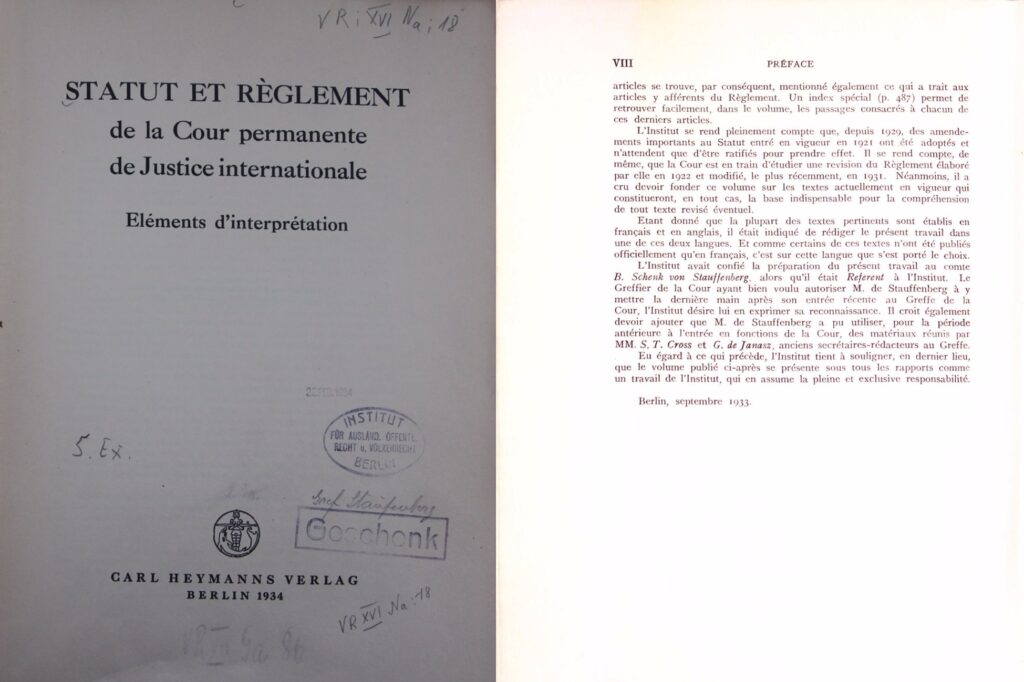

Abschließend sei noch kurz, wie oben angekündigt, ein Wort zum „geistigen“ Input des KWI und MPI zum (Ständigen) Internationalen Gerichtshof gesagt. Hierbei kann es aber nicht um die unzähligen wissenschaftlichen Arbeiten gehen, die sich mit dem Gericht und seiner Rechtsprechung befassen, sondern es soll nur auf eine Publikation hingewiesen werden, die nach Aussagen aus dem Gerichtshof offenbar auf keinem Schreibtisch der Richter fehlt: Den Kommentar zum Statut des Gerichts, der auf die Initiative der Unterzeichnenden und Andreas Zimmermann während ihrer gemeinsamen Zeit am Institut beruht. Wie alle juristischen Texte, sind auch das Statut und die Verfahrensordnung des Gerichts interpretationsfähig und -bedürftig. Daher ist es erforderlich, dass die Auslegung der Bestimmungen durch den Gerichtshof selbst dokumentiert und kritisch begleitet wird. Dabei hilft bekanntlich besonders ein Kommentar, der diese Fragen kontinuierlich aufarbeitet und analysiert, eine Publikationsart, für die deutsche Juristen allgemein bekannt sind. Und in dieser Tradition stand dann auch bereits der erste Kommentar zum Statut und der Verfahrensordnung des StIGH, der im Jahre 1934 vom KWI herausgegeben wurde. Nur im Vorwort erfährt man, dass die Hauptarbeit dieses Werks von Berthold Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg geleistet worden ist, der aber nicht als Autor erscheint und diese Arbeit im Wesentlichen während seiner Zeit als Mitarbeiter der Kanzlei des StIGH vorgenommen hat.

Abschließend sei noch kurz, wie oben angekündigt, ein Wort zum „geistigen“ Input des KWI und MPI zum (Ständigen) Internationalen Gerichtshof gesagt. Hierbei kann es aber nicht um die unzähligen wissenschaftlichen Arbeiten gehen, die sich mit dem Gericht und seiner Rechtsprechung befassen, sondern es soll nur auf eine Publikation hingewiesen werden, die nach Aussagen aus dem Gerichtshof offenbar auf keinem Schreibtisch der Richter fehlt: Den Kommentar zum Statut des Gerichts, der auf die Initiative der Unterzeichnenden und Andreas Zimmermann während ihrer gemeinsamen Zeit am Institut beruht. Wie alle juristischen Texte, sind auch das Statut und die Verfahrensordnung des Gerichts interpretationsfähig und -bedürftig. Daher ist es erforderlich, dass die Auslegung der Bestimmungen durch den Gerichtshof selbst dokumentiert und kritisch begleitet wird. Dabei hilft bekanntlich besonders ein Kommentar, der diese Fragen kontinuierlich aufarbeitet und analysiert, eine Publikationsart, für die deutsche Juristen allgemein bekannt sind. Und in dieser Tradition stand dann auch bereits der erste Kommentar zum Statut und der Verfahrensordnung des StIGH, der im Jahre 1934 vom KWI herausgegeben wurde. Nur im Vorwort erfährt man, dass die Hauptarbeit dieses Werks von Berthold Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg geleistet worden ist, der aber nicht als Autor erscheint und diese Arbeit im Wesentlichen während seiner Zeit als Mitarbeiter der Kanzlei des StIGH vorgenommen hat.

In dieser Ausgabe des Statut-Kommentars aus dem MPIL-Bestand verweist nicht nur das Vorwort, sondern auch eine handschriftliche Notiz auf Berthold Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg, wenn auch mit einem fehlenden „f“.

Dieser erste Kommentar ist noch auf Französisch verfasst, einer der beiden offiziellen Sprachen des Gerichts. Er umfasst 498 Seiten und bearbeitet und kommentiert die einzelnen Bestimmungen des Statuts sowie der jeweils einschlägigen Vorschriften der Verfahrensordnung, wobei immer zunächst ein Blick in die Geschichte der Vorschrift geworfen und dann die praktische Anwendung anhand der einschlägigen Rechtsprechung analysiert wird. Dieser Kommentar – und das ist bemerkenswert – war überwiegend von nur einem Wissenschaftler allein erarbeitet worden und hat lange auf einen Nachfolger warten müssen. Als Hermann Mosler zum Richter am IGH berufen wurde, brachte er den Gedanken ins Gespräch, dass das MPI die Tradition fortsetzen sollte und trug diese Idee insbesondere an die Verfasserin dieses Beitrags heran, die damals hauptamtlich für das Referat IGH zuständig war.[32] Es war aber sofort klar, dass eine einzelne Person diese Arbeit nicht mehr durchführen konnte, sondern dass ein größeres Team eingesetzt werden musste. Der Gedanke blieb präsent und konnte erst verwirklicht werden, als Andreas Zimmermann ein Konzept für das Vorgehen entwickelte, in welchem die Publikation nicht mehr vom MPI als Hauptverantwortlichen getragen wurde, sondern als „freie“ Publikation in der Verantwortung der Herausgeber erarbeitet wurde. Die erste Auflage[33] erschien 2006, also mit einem beachtlichen Abstand zum Werk von Stauffenberg. Insgesamt etwa 50 Autoren aus aller Welt konnten verpflichtet werden, die Kommentierung der Artikel anhand der Rechtsprechung des IGH zu übernehmen und das daraus resultierende Werk, das bei Oxford University Press in englischer Sprache erschien, umfasste knapp 1580 Seiten. Seitdem erscheint im Abstand von etwa fünf Jahren eine Neuauflage – die bislang letzte, die dritte, im Jahr 2019[34] – und Vorüberlegungen für eine vierte Auflage werden derzeit angestellt. Der Herausgeberkreis hat sich im Lauf der Zeit geändert, wobei die konstante treibende und organisatorisch unermüdlich aktive Kraft Andreas Zimmermann geblieben ist. In diesem Zusammenhang darf natürlich auch sein hervorragendes Team an der Universität Potsdam nicht unerwähnt bleiben, das unschätzbare Leistungen bei der Fertigstellung dieser Publikation erbringt.

IV. Schlussbemerkung

Dieser summarische Überblick über die nicht unbedeutende Rolle, die frühere und gegenwärtige Mitarbeiter des KWI und MPI im StIGH und IGH gespielt haben und noch spielen, belegt die Bedeutung der Vermittlung intensiver Kenntnisse in allen Bereichen des Völkerrechts, die nach wie vor neben den Universitäten vor allem auch von einer wissenschaftlichen Institution wie dem heutigen MPI geleistet werden kann. Angesichts der Ausweitung des Völkerrechts auf Bereiche, die einst als rein innerstaatliche Angelegenheiten betrachtet wurden, ist diese Aufgabe wichtiger denn je und zeigt Auswirkungen nicht nur mit Blick auf den IGH, sondern auch auf die Präsenz von Mitarbeitern des MPI in anderen internationalen Gerichten wie dem Europäischen Menschenrechtsgerichtshof und dem Gerichtshof der Europäischen Union, dem Seegerichtshof und zahlreichen internationalen Schiedsgerichten. Dass diese Tradition erhalten bleibt, ist von größter Bedeutung, angesichts der heutigen Weltlage, in der das Völkerrecht eine immer größere Rolle spielt und damit insbesondere auch die Organe, die eingesetzt sind, um seine Beachtung sicherzustellen.

[1] Jan Klabbers, Gazing at Europe: The Epistemic Authority of the MPIL, MPIL100.de.

[2] Foto: AMPG, Bruns, Viktor, II_1.

[3] Der Ständige Schiedshof, der in der Konvention von 1899 zur Friedlichen Beilegung von Streitigkeiten gegründet wurde, besteht im Wesentlichen aus einer Liste von Juristen, auf die jeder Mitgliedstaat vier Personen setzen kann, auf die als Richter in Schiedsverfahren zurückgegriffen werden kann. Diesen Personen ist das Vorschlagsrecht der IGH-Richter-Kandidaten übertragen, wobei jede Gruppe vier Personen vorschlagen kann, von denen nur zwei die Staatsangehörigkeit der Gruppe haben dürfen. Für Staaten, die nicht Partei des PCA sind, ist eine entsprechende alternative Lösung vorgesehen.

Die deutsche nationale Gruppe besteht derzeit aus Doris König, Stefan Oeter (früher Referent am MPIL), Anne Peters (derzeit Direktorin des MPIL) sowie Andreas Zimmermann (ebenfalls vormals Referent am MPIL).

[4] Auch ad hoc Richter, die von Parteien eines Streits benannt werden können, die keinen Richter ihrer Nationalität auf der Richterbank haben, sollen „vorzugsweise“ (Art. 31 Abs.2 Statut) aus dieser Liste gewählt werden. Allerdings ist es nicht zwingend, dass sie die Nationalität des Staates haben, der sie benannt hat.

[5] Eine Ausnahme davon gab es jedoch 2017, als der Kandidat des Vereinigten Königreichs nicht gewählt wurde und 2023, als der Kandidat aus Russland nicht gewählt wurde.

[6] Bemerkenswert ist, dass Walther Schücking sich danach gegenüber der Reichsregierung geweigert hat, seine Rechtsposition aufzugeben.

[7] StIGH, Jurisdiction of the Courts of Danzig (Pecuniary Claims of Danzig Railway Officials who have Passed into the Polish Service, against the Polish Railways Administration), Advisory Opinion vom 3. März 1928, PCIJ Reports, Series B, No. 15; StIGH, Access to, or Anchorage in, the Port of Danzig of Polish Vessels, Advisory Opinion vom 11. Dezember 1931, PCIJ Reports Series A/B, No. 43; StIGH, Treatment of Polish Nationals and other Persons of Polish Origin or Speech in the Danzig Territory, Advisory Opinion vom 4. Februar 1932, PCIJ Reports Series A/B, No. 44.

[8] PCIJ, Certain German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia (Germany v Poland), Urteil vom 25. August 1925, Preliminary Objections, PCIJ Reports Series A, No. 6 und Urteil vom 25. Mai 1926, Merits, PCIJ Report Series A, No. 7; StIGH, Factory of Chorzów (Germany v Poland), Urteil vom 16. Dezember 1927, Measure of Interim Protection, PCIJ Reports Series A, No. 13 und Urteil vom 13. September 1928, Merits, PCIJ Reports Series A, No. 17.

[9] StIGH, S.S. Wimbledon (United Kingdom, France, Italy & Japan v. Germany), Urteil vom 17. August 1923, PCIJ Reports Series A, No. 1; StIGH, Rights of Minorities in Upper Silesia (Minority Schools) (Germany v Poland), Urteil vom 26. April 1928, PCIJ Reports Series A, No. 15.

[10] IGH, North Sea Continental Shelf (Federal Republic of Germany /Netherlands), (Federal Republic of Germany /Denmark), Urteil vom 20. Februar 1969.

[11] IGH, Certain Property (Liechtenstein v Germany), Preliminary Objections, Urteil vom 10.02.2005, ICJ Reports 2005, 6.

[12] IGH, Certain Activities Carried out by Nicaragua in the Border Area (Costa Rica v Nicaragua), Compensation, Urteil vom 02.02.2018, ICJ Reports 2018, 15.

[13] IGH, Dispute Over the Status and Use of the Waters of the Silala (Chile v Bolivia), Merits, including counter-claims of Bolivia, Urteil vom 01.12.2022, ICJ Reports 2022, 614.

[14] ICJ, Costa Rica v Nicaragua (Fn. 12), Rn. 15.

[15] Im Fall Arbitral Award of 3 August 1899 (Guyana v Venezuela) für Guyana und im Fall Legal and Maritime Delimitation and Sovereignty over Islands (Gabon v Equatorial Guinea) für Equatorial Guinea.

[16] Er war von 2003-2008 Mitglied im Fachbeitrat des Instituts, und von 2010- 2023 Mitglied im Kuratorium.

[17] Carl-August Fleischhauer, Die Grenzen der sachlichen Zuständigkeit des Bundeserfassungsgerichts bei der Kontrolle der gesetzgebenden Gewalt, der Staatsleitung und den politischen Parteien, Heidelberg 1960. Das Promotionsrecht steht bekanntlich nur den Universitäten zu, was aber für das MPI kein Problem darstellt, weil alle Direktoren auch immer offiziell in die Universitätslehre eingebunden sind.

[18] Georg Nolte, Beleidigungsschutz in der freiheitlichen Demokratie / Defamation Law in Democratic States, Beiträge zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht Bd. 105, Heidelberg: Springer 1999.

[19] Georg Nolte, Eingreifen auf Einladung: Zur völkerrechtlichen Zulässigkeit des Einsatzes fremder Truppen in internen Konflikten auf Einladung der Regierung, Beiträge zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht Bd. 136, Heidelberg: Springer 1999.

[20] 1931 im Streit über die deutsch-österreichische Zollunion und 1933 zur polnischen Agrarreform.

[21] Foto: Privatarchiv Rainer Noltenius.

[22] Siehe: Carlo Schmid, Erinnerungen, 2. Aufl., Stuttgart: Hirzel 2008, 131; Petra Weber, Carlo Schmid. Eine Biographie, Berlin: Suhrkamp 1996, 66 ff. Schmid hatte den StIGH auch zum Thema seiner Habilitationsschrift gemacht: Karl [damals noch dieser Name] Schmid, Die Rechtsprechung des Ständigen Internationalen Gerichtshofs, Stuttgart: Ferdinand Enke 1932. Von Stauffenberg war von 1929 -1931 Referent am KWI und von 1931-1933 „redigierender“ Sekretär in der Kanzlei des StIGH. 1933 kehrte er ans KWI zurück. Siehe zu Stauffenberg unten Punkt III.

[23] Siehe: Reinhard Rürup/Michael Schüring, Schicksale und Karrieren. Gedenkbuch für die von den Nationalsozialisten aus der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft vertriebenen Forscherinnen und Forscher, Göttingen: Wallstein 2008, 239-240.

[24] Friedrich Berber war nur für einen befristeten Aufenthalt am KWI beschäftigt, aber kein Mitarbeiter des Instituts. Siehe: Fritz [Friedrich] Berber, Sicherheit und Gerechtigkeit. Eine gemeinverständliche Einführung in die Hauptprobleme der Völkerrechtspolitik, Berlin: Carl Heymanns Verlag, 1934; Friedrich Berber, Zwischen Macht und Gewissen. Lebenserinnerungen, herausgegeben von Ingrid Strauss, München: C.H. Beck: 1986, 68-69; siehe auch: Katharina Rietzler, Friedrich Berber and the Politics of International Law, MPIL100.de.

[25] IGH, Alleged Breaches of Certain International Obligations in respect of the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Provisional measures, Order vom 30.04.2024.

[26] Foto: Anne Peters.

[27] IGH, Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Gutachten vom 09.06.2004, ICJ Reports 2004, 136.

[28] IGH, Jurisdictional Immunities of the State (Germany v. Italy: Greece intervening), Urteil vom 03.02.2012, ICJ Reports 2012, 99.

[29] IGH, Legal Consequences arising from the policies and practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Including East Jerusalem, Gutachten vom 19.07.2024.

[30] Foto: UN Photo/ICJ-CIJ/Frank van Beek. Bereitgestellt für die editorische Nutzung durch den IGH.

[31] Prof. Frowein hatte mich im Fall Certain Property (Liechtenstein v Germany) bei der Vorbereitung des von ihm zu behandelnden Aspekts der Zuständigkeit des Gerichtshofs einbezogen. In dem Fall ging es bekanntlich um angebliche Entscheidungen Deutschlands, Eigentum von Liechtensteiner Staatsangehörigen, das zu Reparationszwecken nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg enteignet worden war, ohne Zusicherung von Entschädigung als deutsches Vermögen zu behandeln. Liechtenstein bezog sich zur Stützung seiner Anträge auf die Benes- Dekrete von 1945, auf deren Grundlage deutsches Vermögen enteignet worden war, das auf dem Staatsgebiet der damaligen Tschechoslowakei belegen war. Vor deutschen Gerichten, insbesondere vor dem Bundesverfassungsgericht mit Urteil vom 28. Januar 1998, war immer die Zulässigkeit der Klage verneint worden mit Blick auf Art. 3 Abs.3 Teil VI des Vertrags über die Regelung von aus Krieg und Besatzung entstandener Fragen vom 26. Mai 1952. Vor dem IGH scheiterte die Klage Liechtensteins an der Unzuständigkeit des Gerichtshofs. Als Zuständigkeitsgrundlage hatte Liechtenstein sich auf das Europäische Übereinkommen zur Friedlichen Beilegung von Streitigkeiten von 1957 berufen. Da nach diesem Abkommen die Zuständigkeit des IGH nur für Streitigkeiten gilt, die nach Inkrafttreten des Abkommens zwischen den Parteien entstanden sind, im konkreten Fall der 18. Februar 1980. Da der Streit aber auf die Benes-Dekrete von 1945 und nicht auf die spätere deutsche Rechtsprechung zurückging, wies der IGH die Klage wegen mangelnder Zuständigkeit ab.

[32] Wie in mehreren Blogs bereits erwähnt, hatte jeder Referent des Instituts sog. Referatsgebiete zu betreuen, die natürlich regelmäßig wechselten. Dazu gehörte in der Regel mindestens ein Staat und eine internationale Organisation oder Institution. Aufgabe war es, über jede Entwicklung in diesen Referatsgebieten regelmäßig in der montäglichen Besprechung vorzutragen, was den enormen Vorteil hatte, dass alle Mitarbeiter auf dem neusten Stand von Verfassungsänderungen oder anderen öffentlich-rechtlichen Entwicklungen in nahezu allen Staaten der Welt informiert waren und ebenso über Aktivitäten und Entwicklungen internationaler Organisationen.

[33] Herausgeber waren A. Zimmermann, C. Tomuschat und K. Oellers-Frahm.

[34] Herausgeber dieser Auflage sind A. Zimmermann und C. Tams mit einem Umfang von inzwischen nahezu 2000 Seiten: Die 2. Auflage erschien 2012, herausgegeben von A. Zimmermann, C. Tomuschat, K. Oellers-Frahm und C.J. Tams mit einem Umfang von etwa 1750 Seiten.

English

Personnel and Intellectual Input of the KWI and MPI into the Peace Palace at The Hague

As Jan Klabbers has rightly underlined in his contribution[1], the Kaiser‑Wilhelm‑Institute (KWI) as well as the Max‑Planck‑Institute (MPI) for Comparative Public Law and International Law can be regarded as reservoirs for filling high ranking positions in the international and national domain. Therefore, it does not come as a surprise that among the judges of international courts and tribunals, numerous persons can be found who have been (or are) related to the institute. This blog will investigate this phenomenon with regard to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and its predecessor, the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ). In the context of the institute’s 100-year anniversary, the relationship between these institutions is of relevance for a number of reasons. On the one hand, they were founded within a very short period of one another and are both devoted to international law, which, at that time, only played a modest role. On the other hand, there is my own personal connection, as the primary focus of my research at the institute centered around this topic. In light of this, I would like to begin by addressing the question of whether judges of these institutions came from the KWI/MPI (I). Subsequently, this article will investigate whether German international lawyers from the institute have acted as counsel or agent in contentious cases or advisory opinions before the PCIJ and the ICJ. This aspect is more difficult to analyze, and can only be presented here exemplarily, since a detailed investigation would go beyond the limits of this blog (II). And thirdly and finally, the “intellectual input” of the institute to the work of the PCIJ and ICJ will briefly be touched on (III).

I. German Lawyers as Judges at the PCIJ and the ICJ

The PCIJ and the ICJ are both composed of 15 permanent judges, each elected for a term of nine years, and no two of whom may be nationals of the same state. (Art. 3, para. 1 of the Statute). In addition, judges ad hoc may be chosen for a particular case by a party which has no judge of its nationality on the bench (Art. 31 Statute). Moreover, all members of the Court (that’s to say all member states of the UN) can present their legal position to a question presented to the Court for delivering an advisory opinion (Art. 66 Statute).

Walther Schücking (left) and Viktor Bruns in Den Haag (undated photo)[2]

With a view to the fact that the United Nations consists of 193 member states, and that the International Court shall assure “the representation of the main forms of civilization and of the principal legal systems of the world” (Art. 9 Statute), the election of the judges is of utmost importance. Without going too heavily into the election details laid down in Arts. 2-19 of the Statute, it remains nevertheless important to explain the preconditions under which German lawyers may be elected to the Court. In this respect, the question of how to achieve candidacy in the first place is highly relevant. The idea that states should present their own candidates, which seems at first glance the most obvious approach, was not accepted (and with good reason), namely, this is because the list of candidates is intended to be, to the highest degree possible, independent from political influence. Accordingly, the agreed upon regulation stipulates that candidates are to be nominated on the basis of a list, that is established by a complicated procedure by the national groups of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA).[3] The election then takes place simultaneously in the Security Council and General Assembly independently of one another (without application of the right of veto in the Security Council). Every three years, one third of the judges are elected, and with re-election being possible (Art. 13).[4] Although no provision exists in this regard, each permanent member of the Security Council has a judge of its nationality on the bench.[5] The remaining ten judges are elected on the basis of quotas, which are accorded to the regional groups determined in the framework of the United Nations in 1963. Since 2017, the allocation of seats, including the judges of the nationality of one of the permanent members of the Security Council, is as follows: Western Europe and Other Countries (WEOC) is represented by four judges, Eastern Europe by two judges, Latin America also by two judges, Asia by four judges and Africa by three judges. As the United States of America are part of the WEOC, only one seat remains for this group to be filled by “free” choice: Three places in this group are reserved to nationals of the permanent members of the Security Council: namely the United States of America, France and the United Kingdom. In 2017, however, the candidate from the United Kingdom was not elected, meaning only the United States and France currently have a judge of their nationality on the bench. The remaining two seats are filled by Australia (Charlesworth) and Germany (Nolte).

The PCIJ, founded in 1922, was the first permanent international court ever. It dates thus earlier than the KWI. During its existence there was only one judge of German nationality on its Bench, namely Walther Schücking, the then Director of the Institute for International Law at Kiel, nowadays the Walther‑Schücking‑Institute. Since 1921 he was listed in the PCA as an eligible ad hoc judge, and in 1931 he was elected judge of the PCIJ. He was unable, however, to fulfill his term of office, because he died in 1935. His seat was not filled by a German lawyer, because Germany had not only left the League of Nations in 1933, but also cancelled its membership in the statute of the PCIJ.[6]

There have been three German lawyers working as judges ad hoc in procedures before the PCIJ: Viktor Bruns[7], Ernst Rabel[8] and the already mentioned Walther Schücking[9]. Thus, Viktor Bruns was the first German lawyer from the KWI engaged as judge, or, more precisely, judge ad hoc in the PCIJ.

So far, there have been four judges of German nationality at the ICJ: Hermann Mosler (1976 – 1985); Carl‑August Fleischhauer (1994 – 2003); Bruno Simma (2003-2012) and Georg Nolte (since 2021). In the case of Hermann Mosler, his route to judgeship came via his role as a judge ad hoc in the case North Sea Continental Shelf.[10] Similarly, Carl‑August Fleischhauer and Bruno Simma acted before the Court in the capacity of judges ad hoc, but only after their term of office as judge. Fleischhauer, whose term as judge of the ICJ had ended in 2003, was directly afterwards nominated as judge ad hoc by Germany in the case Certain Property, which had been pending before the Court since 2001.[11] At this time, Bruno Simma was already sitting on the bench, but as he had been previously involved in the question at stake in his function as member of the Council for International Law of the Foreign Office, he was prevented from sitting on the bench by Art. 17, para 2 of the Statute. Bruno Simma was later nominated by Costa Rica as judge ad hoc in the case Maritime Delimitation in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean.[12] Furthermore, he acted as judge ad hoc nominated by Chile in the case Dispute over the Status and Use of the Waters of the Silala[13] and also, as judge ad hoc nominated by Costa Rica, in the case Land Boundary in the Northern Part of the Isla Portillo.[14]

Besides the three persons who also acted before (as Hermann Mosler did) or after their term of office in the Court as judge ad hoc, the only other lawyer from the MPI to appear acting in the same capacity is Rüdiger Wolfrum, who did not serve as a judge at the ICJ but instead at the International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea. He is currently sitting as judge ad hoc in two cases before the ICJ.[15]

With the exception of Bruno Simma who had never been an official employee of the institute, although he was always closely related to it[16], the other three judges referred to above all came from the institute. When Hermann Mosler was elected as judge of the ICJ, he was also Director of the institute. Carl‑August Fleischhauer had, after passing the second State Examination, served from 1960 onwards as a research fellow at the MPI where he wrote his doctoral thesis. In 1961 he was conferred a doctorate degree at the University of Heidelberg[17]. Shortly afterwards he terminated his employment at the MPI and began an impressive career in the Foreign Office, before, sometime later, he became Under Secretary‑General and Legal Counsel of the United Nations. He remained closely associated with the MPI through his membership in the Kuratorium from 1975 to 2002.

The academic career of Georg Nolte, whose term of office as judge in the ICJ started in 2021, was closely linked to the MPI, a relationship which has continued through his activity in the Kuratorium of the Institute. From 1984 to 1990, alongside his legal preparatory service (Referendarzeit), he also worked on his doctoral thesis and was employed at the institute, where he served from 1992 to 1999 as a research fellow. In 1991, he obtained his doctoral degree under the supervision of his academic mentor Jochen Abr. Frowein, then Director at the institute[18], and, in 1998, was awarded his habilitation degree, once more under the supervision of Frowein.[19]

In light of this information and in the context of the fact that usually only one European lawyer can be elected as judge at the ICJ (besides the three judges of the nationality of the veto-powers United States, France and (until 2017) the United Kingdom), the significant impact of the MPI in forming international lawyers qualified for the highest offices is undeniable.

II. Members of the Institute Acting as Counsel in Proceedings Before the International Court

As is also the case with national legal procedures, the parties in cases before international courts and tribunals are represented by “advocates”, although there is no requirement comparable to the admission of lawyers under national law. Art. 42 of the Statutes states simply that “the parties shall be represented by agents”: These are the contact persons for the Court, and are – for practical reasons -, as a rule, the diplomatic or consular representatives of the parties at The Hague. The agents can – and in general always do – have “the assistance of counsel or advocates” who represent the parties by drafting the pleadings and presenting the parties’ argument in the oral proceedings. Neither the Statute nor the Rules of Procedure of the Court stipulate any details concerning the qualification of these persons. The basic assumption is that states will only entrust this function to “adequately qualified persons”, which, of course, lies in their own interest and has therefore generally been the case in practice. It is at this point that the KWI and the MPI once again come into view, because of their particular focus on international law that is the subject matter of all cases before the International Court.

Among the members of the KWI, which was founded two years after the creation of the PCIJ, it was only Viktor Bruns who served, as mentioned above, in several cases as a judge ad hoc before the PCIJ, and who also acted in two other cases as counsel for Germany.[20]

Viktor Bruns (left) acting as a counsel (undated photo)[21]

From the information on other KWI employees, only Carlo Schmid and Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg can be identified as having been involved in cases before the PCIJ. Both were involved by Viktor Bruns in the cases referred to above, in which he acted as counsel for Germany.[22] Erich Kaufmann, who served from 1927 to 1934 as academic counsel of the KWI[23], and his assistant Friedrich Berber[24], also acted as counsel before the PCIJ, but had no official affiliation to the KWI.

Coming now to the involvement of former (and current) lawyers from the MPI as counsel (not just for Germany) in procedures before the ICJ, the situation is more impressive. Prof. Frowein, for example, has acted as counsel for Germany in the case Certain Property (Liechtenstein v. Germany) and was involved in the case Land and Maritime Boundary Between Cameroon and Nigeria (Cameroon v Nigeria), but resigned from his appointment during the proceedings. In the advisory opinion concerning the question of the independence of Kosovo he presented the legal position of Albania. The present director of the MPI, Anne Peters, was part of the team representing the legal position of Germany in the case Nicaragua v Germany[25]; in which until now, only an order on the request for interim protection has been delivered, meaning she remains involved in this case.

Agents of Germany in the case „Nicaragua v Germany“ (from left to right): Paolo Palchetti, Samuel Wordsworth, Anne Peters, Christian J. Tams[26]

With regard to former members of the institute, mention has to be made of Michael Bothe, who represented in 2003/2004 the League of Arab States in the advisory opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory[27].

Equally of note, is Christian Tomuschat, who acted as counsel for Germany in the Immunities case between Italy and Germany[28]. There is, however, a former member of the MPI who occupies an outstanding position in this respect: He acted (or continues to act) in 16 cases as counsel for one of the parties and is thus regarded as a member of the “bar”, the “permanent advocacy” of the ICJ, which does, however, not exist as an “official” organ. It would be going too far to list here all these cases, and may thus be sufficient to name only those that are still pending or have been decided very recently. Noteworthy are the still‑pending advisory opinion concerning the Obligations of States in respect of Climate Change; the (second) case concerning Questions of jurisdictional Immunities of the State and Measures of Constraint against State-owned Property (Italy v Germany); as well as the case concerning the Arbitral Award of 3 October 1899 (Guyana v Venezuela). Both are still pending, with the latter being the case in which, as was already mentioned, Rüdiger Wolfrum is the judge ad hoc nominated by Guyana. Finally, the only recently concluded very important advisory opinion on the Legal Consequences arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Including East Jerusalem,[29] in which Andreas Zimmermann acted as counsel for the government of the State of Palestine.

Impressive: The opening of the hearings in the case “Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates v Qatar” in 2019[30]

Typically, the counsels are assisted by researchers from the institute (or their chair) in drafting pleadings and memorials and preparing for the oral proceedings. Sometimes, they even have the privilege of accompanying the counsel to the oral proceedings in The Hague, which is, of course, a real highlight for those involved. From my own experience[31], I can say that participating in a case in the impressive premises of the Peace Palace at The Hague is an unforgettable experience. Equally impressive are the details of the actual proceedings: For example, great emphasis is placed on maintaining a strict separation between the parties and their counsels and the representatives and agents of the other party, which, for example, entails taking certain precautions for coffee breaks, office allocations, and so on. Furthermore, full commitment is required because, as a rule, only the evening and night hours are available for preparing an adequate response after the oral presentation of the opposing party or to questions from the judges after one’s own pleading.

III. Intellectual Input Towards the Work of the International Court

Finally, mention should be made of the “intellectual input” of the KWI and MPI to the work of the (Permanent) Court of International Justice. It would be impossible here, however, to address the countless academic publications devoted to the Court and its jurisprudence, so instead I wish only to draw attention to one publication in particular, which, according to information from the Court, is obviously present on the desk of every judge: Namely, the Commentary on the Statute of the Court, a publication that Andreas Zimmermann and myself developed during our common time at the institute. Like all legal texts, the Statute and the Rules of Procedure of the Court are not only open to, but also in need of interpretation. Therefore, it is important that the interpretation of the provisions by the Court itself is documented and critically analyzed. In this respect, it is well known that commentaries are a particularly effective means of continuously updating and analyzing these developments, and are, moreover, a form of publication that German legal academia is renowned for. The first commentary on the Statute and Rules of Procedure of the Permanent Court of International Justice was published in 1934 by the KWI and also follows this tradition. Only in the preface is it mentioned that the bulk of the work of the publication was done by Berthold Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg, who is, however, not mentioned as the author of the commentary, and who essentially carried out this work during his time as an associate in the Registry of the PCIJ.

In this edition of the commentary from the MPIL library, not just the preface, but also a handwritten note points to Berthold Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg, even if his name is misspelled with only one “f”.

This first commentary was published in French, one of the two official languages of the Court. It is 498 pages long and analyzes the provisions of the Statute and the related Rules of Procedure by first referring always to the history of the provisions, and then to the practical application in the jurisprudence of the Court. This commentary was written essentially by only one person alone – a fact that remains truly remarkable. It was a long time before the 1934 publication found a successor. When Hermann Mosler was elected judge at the ICJ, he raised the idea that the MPI should continue the tradition of publishing a commentary, addressing myself in particular, as at that time I was officially responsible for the “Referat” International Court of Justice.[32] It was, however, immediately obvious that a single person alone could not execute this task, and it would instead require a larger team to manage the project. The idea remained on the agenda but could only be realized when Andreas Zimmermann developed an idea for its implementation, whereby the MPI would no longer be held as the main responsible organ, and the commentary would instead be enacted as a “free” publication under the responsibility of the editors. The first edition[33] appeared in 2006, a remarkably long time after Stauffenberg’s commentary. Altogether, nearly 50 authors from all over the world could be engaged to comment on the articles of the Statute on the basis of the jurisprudence of the Court. The outcome was a book edited by Oxford University Press in English counting roughly 1580 pages. Since then, a new edition was published about every five years, the most recent of which is the third edition from 2019[34]. Work on the fourth edition is already underway. The team of editors has changed over time, but the permanent active driving force is still Andreas Zimmermann. In this regard, mention should also be made of his excellent team at the University of Potsdam, who do an inestimable job in the production of the manuscript.

IV. Final Remark

This summary of the rather remarkable role that former and present researchers of the KWI and MPI have played – and still play – in the PCIJ and the ICJ demonstrates the importance of procuring knowledge in all fields of international law, a task that can be performed by universities, but is most effectively carried out by research institutions like the MPI. In light of the expansion of international law into areas that were once considered purely domestic affairs, the role of institutions like the MPI is more important than ever before. The activities of such organizations have an impact not only with regard to the ICJ, but also through the role of researchers from the MPI sitting in other international courts and tribunals, such as the European Court of Human Rights, the European Court of Justice, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea and numerous international arbitral tribunals. That this tradition of the MPI be continued seems of utmost significance in the present world: International law is playing an increasingly important role on the global stage and, as a consequence, so too are the organs created for guaranteeing its implementation.

Translation from the German original: Karin Oellers-Frahm/Callum Hanks.

[1] Jan Klabbers, Gazing at Europe: The Epistemic Authority of the MPIL, MPIL100.de

[2] Photo: AMPG, Bruns, Viktor, II_1.

[3] The Permanent Court of Arbitration, which was founded by the Convention of 1899 on the Peaceful Settlement of Disputes, is essentially made up of a list of lawyers to which each member State may nominate four persons who may be called upon to sit as judge in an arbitration procedure. These national groups have the right to propose candidates to be elected as judge at the International Court. Each national group may propose four persons, only two of whom may be of the nationality of the proposing group. For those states that are not parties to the Permanent Court of Arbitration, a corresponding alternative solution has been provided for.The German national group is currently composed of Doris König, Stefan Oeter (a former researcher at the Institute), Anne Peters (current Director at the MPIL), and Andreas Zimmermann (also a former researcher at the MPIL).

[4] Also, judges ad hoc who are nominated by a state which has no judge of its nationality on the bench in a particular case, should “preferably” be chosen from among the persons of the national groups of the PCA (Art. 31 para 2 Statute). It is, however, not required that they are of the nationality of the nominating State.

[5] An exception to this tradition occurred, however, in 2017 when the candidate of the United Kingdom was not elected, and again in 2023, when the Russian candidate was not elected.

[6] It is interesting to note, in this context, that Walther Schücking resisted the government’s request to give up his seat.

[7] PCIJ, Jurisdiction of the Courts of Danzig (Pecuniary Claims of Danzig Railway Officials who have Passed into the Polish Service, against the Polish Railways Administration), Advisory Opinion of 3 March 1928, PCIJ Reports, Series B, No. 15; PCIJ, Access to, or Anchorage in, the Port of Danzig of Polish Vessels, Advisory Opinion of 11 December 1931, PCIJ Reports Series A/B, No. 43; PCIJ, Treatment of Polish Nationals and other Persons of Polish Origin or Speech in the Danzig Territory, Advisory Opinion of 4 February 1932, PCIJ Reports Series A/B, No. 44.

[8] PCIJ, Certain German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia (Germany v Poland), Judgement of 25 August 1925, Preliminary Objections, PCIJ Reports Series A, No. 6 and Judgement of 25 May 1926, Merits, PCIJ Report Series A, No. 7; PCIJ, Factory of Chorzów (Germany v Poland), Judgement of 16 December 1927, Measure of Interim Protection, PCIJ Reports Series A, No. 13 and Judgement of 13 September 1928, Merits, PCIJ Reports Series A, No. 17.

[9] PCIJ, S.S. Wimbledon (United Kingdom, France, Italy & Japan v. Germany), Judgment of 17 August 1923, PCIJ Reports Series A, No. 1; PCIJ, Rights of Minorities in Upper Silesia (Minority Schools) (Germany v Poland), Judgement of 26 April 1928, PCIJ Reports Series A, No. 15.

[10] ICJ, North Sea Continental Shelf (Federal Republic of Germany v Netherlands) and (Federal Republic of Germany v Denmark), Judgment of 20.02.1969, ICJ Reports 1969, 3.

[11] ICJ, Certain Property (Liechtenstein v Germany), Preliminary Objections, Judgment of 10.02.2005, ICJ Reports 2005, 6.

[12] ICJ, Certain Activities Carried out by Nicaragua in the Border Area (Costa Rica v Nicaragua), Compensation, Judgment of 02.02.2018, ICJ Reports 2018, 15.

[13] ICJ, Dispute Over the Status and Use of the Waters of the Silala (Chile v Bolivia), Merits, including counter-claims of Bolivia, Judgment of 01.12.2022, ICJ Reports 2022, 614.

[14] ICJ, Costa Rica v Nicaragua (Fn. 12), para. 15.

[15] In the cases Arbitral Award of 3 August 1899 (Guyana v Venezuela), nominated by Venezuela, and in Legal and Maritime Delimitation and Sovereignty over Islands (Gabon v Equatorial Guinea), nominated by Equatorial Guinea.

[16] From 2003 to 2008 he was member of the Fachbeirat of the Institute, and from 2010 to 2023 a member of the Kuratorium.

[17] Carl-August Fleischhauer, Die Grenzen der sachlichen Zuständigkeit des Bundesverfassungsgerichts bei der Kontrolle der gesetzgebenden Gewalt, der Staatsleitung und den politischen Parteien, Heidelberg: Univ. Diss. 1960. The right to confer doctoral degrees is conferred to the universities alone, which does not, however, constitute a problem for the MPIL, because its directors are always officially integrated into the University.

[18] Georg Nolte, Beleidigungsschutz in der freiheitlichen Demokratie / Defamation Law in Democratic States, Beiträge zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht Vol. 105, Heidelberg: Springer 1999.

[19] Georg Nolte, Eingreifen auf Einladung: Zur völkerrechtlichen Zulässigkeit des Einsatzes fremder Truppen in internen Konflikten auf Einladung der Regierung, Beiträge zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht Vol. 136, Heidelberg: Springer 1999.

[20] 1931 in the case concerning the Customs Regime Between Germany and Austria; 1933 in the case concerning the Polish Agrarian Reform.

[21] Photo: Private Archive of Rainer Noltenius.

[22] Cf. Carlo Schmid, Erinnerungen, 2nd. Edition, Stuttgart: Hirzel 2008, 131; Petra Weber, Carlo Schmid. Eine Biographie, Berlin: Suhrkamp 1996, 66 ff. Schmid had also chosen the PCIJ as the subject of his doctoral thesis: Karl [in those days he still used this name] Schmid, Die Rechtsprechung des Ständigen Internationalen Gerichtshofs, Stuttgart: Ferdinand Enke 1932. Von Stauffenberg served from 1929 to 1931 as Research Fellow at the KWI and from 1931 to 1933 as “editing” Secretary in the Registry of the PCIJ. 1933 he returned to the KWI. See also infra III.

[23] Cf. Reinhard Rürup/Michael Schüring, Schicksale und Karrieren. Gedenkbuch für die von den Nationalsozialisten aus der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft vertriebenen Forscherinnen und Forscher, Göttingen: Wallstein 2008, 239-240.

[24] Friedrich Berber was only employed at the KWI for a limited period, but never had an official function at the KWI. Cf. Fritz [Friedrich] Berber, Sicherheit und Gerechtigkeit. Eine gemeinverständliche Einführung in die Hauptprobleme der Völkerrechtspolitik, Berlin: Carl Heymanns Verlag, 1934; Friedrich Berber, Zwischen Macht und Gewissen. Lebenserinnerungen, edited by Ingrid Strauss, Munich: C.H. Beck: 1986, 68-69. Cf., also, Katharina Rietzler, Friedrich Berber and the Politics of International Law, MPIL100.de.

[25] ICJ, Alleged Breaches of Certain International Obligations in respect of the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Provisional measures, Order of 30.04.2024.

[26] Photo: Anne Peters.

[27] ICJ, Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion of 09.06.2004, ICJ Reports 2004, 136.

[28] ICJ, Jurisdictional Immunities of the State (Germany v. Italy: Greece intervening), Judgment of 03.02.2012, ICJ Reports 2012, 99.

[29] ICJ, Legal Consequences arising from the policies and practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Including East Jerusalem, Advisory Opinion of 19.07.2024.

[30] Photo: UN Photo/ICJ-CIJ/Frank van Beek. Made available for editorial use by the ICJ.

[31] I had the privilege of assisting Prof. Frowein in the case Certain Property (Liechtenstein v Germany) in preparing the memorial and the oral pleading on the aspect attributed to him, namely the question of the jurisdiction of the Court. The case concerned alleged decisions of Germany to treat certain property of Liechtenstein nationals as German assets having been seized after the Second World War for the purposes of reparation without ensuring any compensation. Liechtenstein based its claims on the Benes Decrees of 1945 according to which German property located on the territory of what was then Czechoslovakia, was seized. Before German courts, and in particular before the German Constitutional Court in its judgment of 28 January 1998, the claims were regularly dismissed as inadmissible on the basis of Art. 3, para 3, Part VI, of the Convention on the Settlement of Matters Arising out of the War and the Occupation of 26 May 1952. The claim was dismissed by the ICJ for lack of jurisdiction. As its jurisdictional bases Liechtenstein invoked the European Convention for the Peaceful Settlement of Disputes of 29 April 1957. As, according to this Convention, the jurisdiction of the Court only exists for disputes related to facts or situations that arose after the entry into force of the Convention between the parties, namely 18 February 1980. The Court dismissed the case because the real cause of the dispute was not to be found in the German Courts’ decisions, but in the Benes Decrees and the Settlement Convention dating before the entry into force of the Settlement Convention between Germany and Liechtenstein.

[32] As has already been mentioned in several contributions, each research fellow of the MPIL was responsible for so-called Referate, which, of course, changed from time to time. As a rule, the Referate covered at least one state as well as an international organization or institution. Their task was to present during the Monday sessions, any relevant development in their fields, which had the very welcome side effect for all researchers at the Institute of being kept up to date with the newest constitutional developments (or other aspects of public law) of nearly all countries globally as well as of the activities and developments in international organizations.

[33] Edited by A. Zimmermann, C. Tomuschat and K. Oellers-Frahm.

[34] The editors of this edition are A. Zimmermann and C. J. Tams; the volume has nearly 2000 pages. The second edition was published in 2012, edited by A. Zimmermann, C. Tomuschat, K. Oellers-Frahm and C.J. Tams counting some 1750 pages.

Karin Oellers-Frahm ist Senior Research Affiliate am MPIL, wo sie ab 1970 als wissenschaftliche Referentin mit Schwerpunkt internationale Gerichtsbarkeit und Rechtsvergleichung gearbeitet hat.

Karin Oellers-Frahm is a Senior Research Affiliate at the MPIL where she had worked from 1970 onwards as Research fellow focusing on international jurisdiction and comparative law.

The Peace Palace in Den Haag (Photo: Public Domain)

The Peace Palace in Den Haag (Photo: Public Domain)

Pingback: Völkerrecht im Radio. Marianne Grewe-Partsch interviewt das Institut 1966 – MPIL100

Pingback: Eine „ganz unverhoffte Freude“. Eindrücke aus der Gründungszeit des Instituts 1924-1926 – MPIL100

Pingback: Praxisnähe und wissenschaftliche Reflexion. Das Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht – ein „state agent“? – MPIL100

Pingback: Das Institut und das Bundesverfassungsgericht – MPIL100

Pingback: Das MPIL an der Schnittstelle zwischen Wissenschaft und Praxis. Vier Thesen einer Praktikerin und Alumna – MPIL100

Pingback: „Crimes against Humanity“ und die Völkermordkonvention. Kein Thema für das Institut? – MPIL100

Pingback: Völkerrecht im Widerstand? Berthold von Stauffenberg in der Erinnerungskultur des Instituts – MPIL100

Pingback: Viktor Bruns als Richter am Deutsch-Polnischen Gemischten Schiedsgericht – MPIL100

Pingback: MPIL100 – Beginn einer Spurensuche – MPIL100

Pingback: Why Translating Law Means Translating Culture – MPIL100