When rival Sudanese delegations arrived in Heidelberg in 2002, they refused even to share a hotel lobby. Three sleepless weeks later they walked out of the Max Planck Institute with a joint bill of rights that became the spine of Sudan’s 2005 Interim Constitution.

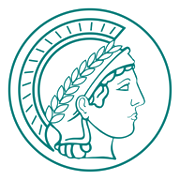

At the center was Rüdiger Wolfrum: international judge, peace-broker, and the first “outsider” ever hired to direct the institute. He insists academia should do more than publish; it should settle real disputes. “The Foreign Office never touched our text,” he recalls, proud of a process that mixed 3 a.m. draft sessions with feedback from chiefs, mayors, and imams.

Wolfrum emphasizes that the advisory group at these negotiations included acclaimed experts from both the Global South and North—among them Judge Tafsir Malick Ndiaye (Senegal), Judge Thomas A. Mensah (Ghana), Prince Raad bin Zeid (Jordan), Professor Fred Morrison (USA), and Ambassador Tono Eitel (Germany). Crucially, representatives from both Sudan and South Sudan were able to fully participate and shape the process. As Wolfrum notes, “A constitution that is imposed — or even merely feels imposed — can never achieve the acceptance necessary for its effectiveness.”

In this MPIL100 conversation with Moritz Vinken, Wolfrum explains how academia can host hard political talks, and why young scholars shouldn’t choose between rigor and relevance—they can, and must, deliver both.

About Rüdiger Wolfrum

As a lawyer, Rüdiger Wolfrum bridged courtroom, classroom, and conflict mediation. As president and long-serving judge of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, he helped shape modern maritime jurisprudence while directing the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law in Heidelberg. A builder of legal knowledge infrastructures, he spearheaded the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law (MPEPIL) and the Journal of the History of International Law (JHIL), and advanced ideas like solidarity as a structural principle of international law. Beyond scholarship, he advised peace and constitution-making processes in Sudan, South Sudan, and Lebanon, designing inclusive, locally grounded negotiations. His work—a blend of doctrine and practice—has influenced courts, scholars, and policymakers, and continues through the Max Planck Foundation for International Peace and the Rule of Law.