In modern and contemporary times, it is not often that one can encounter someone who was a true pioneer. However, for education in public international law at Croatian universities, Juraj Andrassy was the first one in many aspects. A pioneer and a Nestor, the first appointed professor of international law as a designated field, not in combination with another legal discipline, at the Faculty of Law of the University of Zagreb.[1] While the Zagreb Faculty of Law has an unbroken continuity of almost 250 years (the higher education in law in Zagreb started in 1776 and has since continued uninterrupted, despite all changes in legal structure and political circumstances over the two and a half centuries), before Andrassy became a professor of international law, this field had always been joined in with other disciplines such as legal history or constitutional law.

Juraj Andrassy was born in Zagreb on 12 August 1896. His father, Ljudevit Andrassy, was a professor of Roman law at the Zagreb Faculty of Law. Young Juraj followed in the choice of his career, receiving his doctoral title in 1919. Soon after, Andrassy went to Paris, where he studied public law, focusing especially on public international law. Andrassy then moved back to Zagreb, where he started his academic path at the Zagreb Faculty of Law, which would remain his main occupation until the end of his life in 1977.[3]

Portrait of Juraj Andrassy as a young man (undated, painter: Slavko Tomerlin)[4]

In his capacity as professor of international law, Andrassy created what has remained the curricular foundation of education in public international law in Croatia, and even in ex-Yugoslavia, to this day. This included the first postgraduate programme in international (public and private) law and the first textbook on international law written in Croatian language for purposes of education of lawyers.[5] Although significantly revised by his successors at the Zagreb Chair for International Law in light of progressive developments of international law, the structure of this book still provides a basis for the organisation of the Croatian system of general international law. Based on this work, but also his scientific and lexicographical work, Andrassy can be rightfully credited for creating Croatian international law terminology.[6] His names for various legal concepts in international law remain in use by Croatian internationalists and have passed the test of time and usage.

On the international level, Andrassy was a member of the most important learned societies of international law, including the Institut de Droit International, where he became an associate member in 1952, and a full member in 1961.[7] As a member of the Institute, Andrassy twice served as a rapporteur on two different, although somewhat connected resolutions, first on the topic of utilisation of non-maritime international waters (except for navigation) and the second time on measures concerning accidental pollutions of the seas. His reports on both topics resulted in extensive discussions and comments from some of the most eminent international lawyers of the time, finally ending in the adoption of resolutions by the Institute’s plenum in 1961[8] and 1969[9], respectively. Over the years, Andrassy served two terms as vice-president and was elected president of the Institute in 1969. In 1971 he organized the only session of the Institute held in Zagreb up until today.

Juraj Andrassy and the MPIL. A Long and Determined Relationship

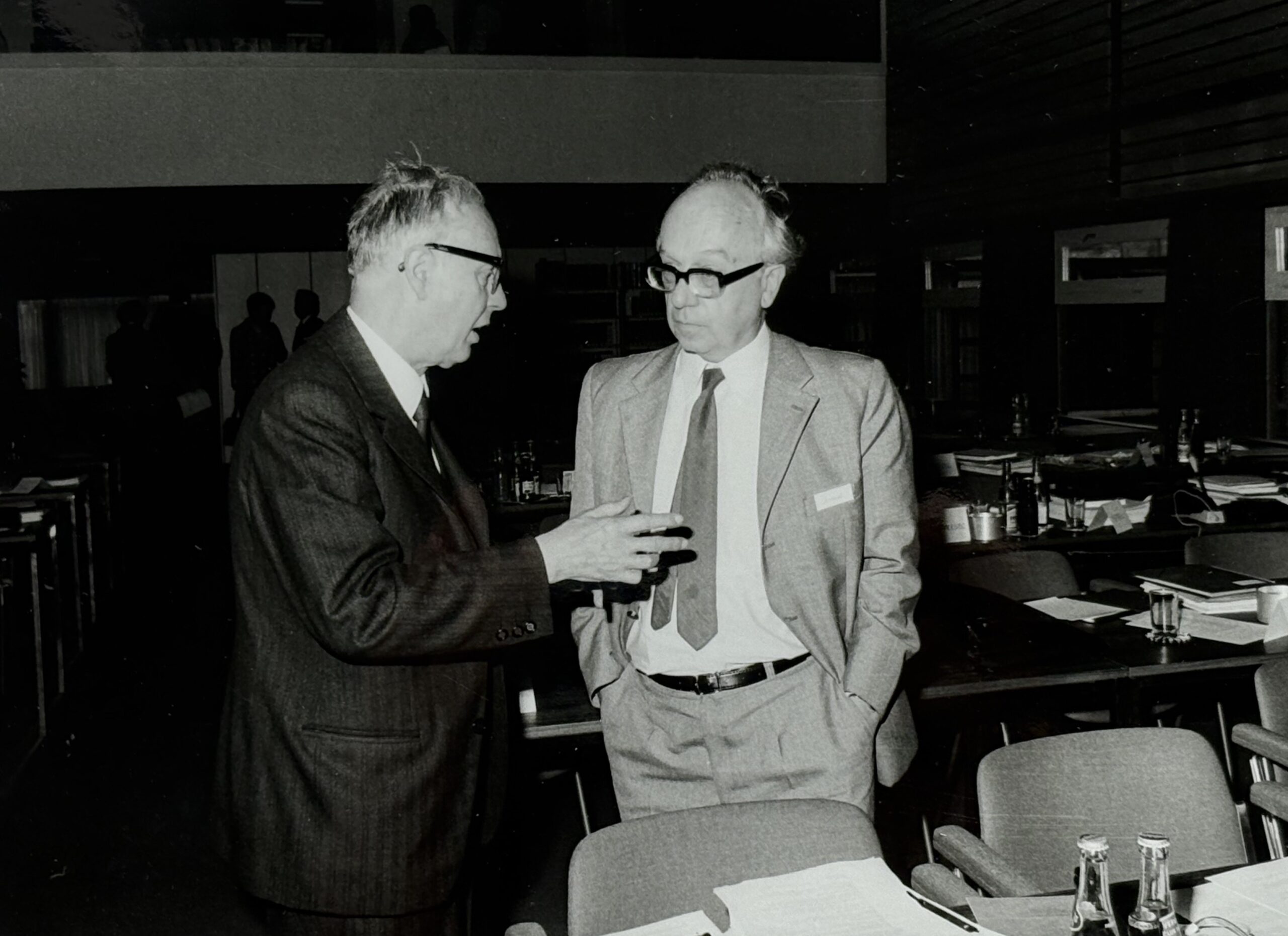

Juraj Andrassy and Helmut Strebel at the Institute’s conference on “Judicial Settlement” in 1972[10]

Andrassy’s association with the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (MPIL) was mostly from a distance due to his commitments in Zagreb, however it remained long lasting and determined. First occasions of cooperation can be traced back to a time that was significant both for the MPIL and for Andrassy himself: In 1951, Andrassy lectured at The Hague Academy for International Law for the second time. At the same time, the MPIL in Heidelberg was going through the first years of its reestablishment after the end of the Second World War and the process of (re-)connecting with colleagues in Europe and beyond. Andrassy’s topic that summer was Les relations internationales de voisinage (“The international relations of neighbourhood”)[11], a concept that he had dealt with across various fields of international law. It was likely in The Hague, that MPIL-Associate and long-standing editor of the its publications, Helmut Strebel, first met Andrassy.[12] Immediately after the summer, in early October of the same year, Strebel wrote to Andrassy inquiring whether he would be willing to write two contributions for the Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentlisches Recht und Völkerrecht (ZaöRV, English title: Heidelberg Journal of International Law, HJIL).[13] Andrassy gladly accepted both offers.[14]

The first one of these is an article accompanying the translation (also provided by Andrassy) of Chapter XI of the Yugoslav Criminal Code (Krivični zakon) of 1951, which constituted a national codification of public international law, such as crimes against humanity. Chapter XI of the Code encompasses ten articles, establishing criminal liability in Yugoslav law of the time for, inter alia, genocide, war crimes, and crimes against cultural heritage. Andrassy, however, in his contribution accompanying the translation, did not restrict himself to providing a commentary or contextualization of the translated Chapter XI, but rather provided a review of public international law aspects of various parts of the Yugoslav Criminal Code, identifying and explaining international legal aspects of it.[15] In the correspondence between Strebel and Andrassy from around the time when this article was published in the HJIL and in Andrassy’s own work one cannot find a direct answer to the question of motivation, namely why Strebel asked Andrassy to write on a topic that was not in the focus of Andrassy’s interest at the time. However, some answers can be deduced from the letters exchanged between the two international law scholars: In these letters, Andrassy and Strebel are discussing the validity of laws in Yugoslavia during, before, and after the occupation of the country during the Second World War.[16] At first glance, one might think that Strebel just had an interest in the emerging postwar Yugoslav legal system. However, one can speculate about another reason, although there are no concrete clues or explicit evidence in the correspondence itself. At the time, the question of war crimes was still the topic of the day, which many international and public lawyers dealt with, as evidenced, inter alia, by the existence of the Institut für Besatzungsfragen (Institute for Occupation Studies), the Heidelberger Juristenkreis and other similar groups in German legal scholarship at the time.[17]

The second, smaller, contribution by Andrassy was a book review. The book, Grundprinzipien des modernen zwischenstaatlichen Nachbarrechts by Hans Thalmann, was published in Zürich in 1951.[18] Andrassy, who himself was a pioneer in the field that Thalmann chose as a main topic of his dissertation, was, judging by his comments in the review, glad to see, read, and review a book by another, as Andrassy himself called him, “pioneer in the field”. Both this review of Thalmann’s book[19] and the aforementioned article were published in HJIL volume 14, the journal’s second postwar volume, dated 1951, but effectively published only in the first months of the following year, 1952.

The correspondence between Strebel and Andrassy continued and in 1953, Andrassy again published an article in the HJIL, this time on another topic, which, at the time, represented an intriguing novelty, while today it can be considered mainly of interest for the history of international law: In February 1953, the so-called Balkan Entente Pact made international headlines. It was an international cooperation and assistance treaty between Yugoslavia, Greece, and Turkey. Considering both the historical and then-recent experiences with difficult relations between the three states, the Pact, which set a tone of peacefulness, coexistence, and cooperation (especially in the light of a USSR aggression that the three signatory states feared) between them, was a significant event. The HJIL editors, almost immediately after the news on the signing of the Pact broke, decided on publishing its integral text (in French). At the same time, they needed a competent international lawyer to provide a commentary to the text. Andrassy accepted their invitation, and his commentary was published accompanying the translation, involving meticulous analysis and carefully formulated conclusions.[20]

In 1958, Andrassy published his longest and most comprehensive contribution to the HJIL. The article, which opened volume 19 of the journal, bears the title Betrachtungen über die Zuständigkeit des Internationalen Gerichtshofes (“Considerations on the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice”).[21] In it, Andrassy studiously develops the theory of jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice, a topic that he investigated for many years: Exactly ten years earlier, he had published a book in Croatian, titled Međunarodno pravosuđe (“International Judiciary”)[22], that discussed similar topics at greater length. His theory, as presented in the article, encompasses a model based on the distinction between functional and treaty-based jurisdiction, aligned with the more traditional divide between jurisdiction ratione personae and ratione materiae.

Over the years, Andrassy published a handful more book reviews in the HJIL: In 1955[23] a review of a book on the law of the sea by Milovan Zoričić, the only Croat that has ever sat on the bench of the International Court of Justice, and a further review in 1958[24].

In 1966, Andrassy published his final contribution to the Journal, this time in French, under the title Les progrès techniques et l’extension du plateau continental (“Technical advances and the extension of the continental shelf.”)[25], another highly debated topic of the time, which occupied Andrassy for many years. In 1951, he had published a monograph in Croatian on the topic, under the title Epikontinentalni pojas (“Continental Shelf”)[26], which created an impetus for him to publish on the question of how advancement of technology should be followed by law. Andrassy made clear that law should engage in meaningful discussion with the technological advancements and reflect them, both in a new convention concerning the continental shelf and in the change of the existing regulations. He made his arguments clear, advocating for the change of Article 1 of the 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf in order to clearly restrict the outer limit of the continental shelf.[27]

It would certainly be an overstatement to claim that the relationship between Andrassy and the MPIL was determinative for either the Croatian professor or the German research institute. However, their relationship was clearly both strong and cordial, reflecting Andrassy’s interest in different fields of public international law, on the one hand, and the MPIL’s eagerness to investigate and inform the international scientific community about important developments of international law, on the other, thereby affirming the Institute’s leading position in the field in a new geopolitical constellation after 1945.

[1] Vladimir Ibler, Juraj Andrassy: The Man and his Work, Jugoslovenska revija za međunarodno parvo 26 (1979), 9.

[2] Photos: Leon Žganec-Brajša.

[3] On Andrassy’s life, see: Vladimir Ibler, La vie et l’oeuvre du Professeur Juraj Andrassy, in: Vladimir Ibler (ed.), Mélanges offerts à Juraj Andrassy/Essays in International Law in Honour of Juraj Andrassy/Festschrift für Juraj Andrassy, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff 1968, VII–XII.

[4] Source: Željko Pavić (ed.), Pravni fakultet u Zagrebu: 1776–1996, Zagreb: Pravni fakultet u Zagrebu 1996.

[5] Božidar Bakotić, En souvenir de Juraj Andrassy, Jugoslovenska revija za međunarodno pravo 26 (1979), 22–23.

[6] Bakotić (fn. 5).

[7] Nina Vajić, Andrassy i Institut za međunarodno pravo, Jugoslovenska revija za međunarodno pravo 26 (1979), 187.

[8] Neuvième Commission/Rapporteur M. Juraj Andrassy, Utilisation des eaux internationales non maritimes (en dehors de la navigation), Annuaire, Institut de droit international Vol. 49 (1961), 370–373.

[9] Douzième Commission/Rapporteur M. Juraj Andrassy, Mesures concernant la pollution accidentelle des milieux marins; Mesures en cas d’accident survenu, Annuaire, Institut de droit international Vol. 53 (1969), 363–369.

[10] Photo: MPIL.

[11] Académie de Droit International de la Haye (ed.), Les relations internationales de voisinage, Collected Courses of The Hague Academy of International Law Vol. 79 (1951), Leiden: Brill 1968.

[12] Letter from Helmut Strebel to Juraj Andrassy, dated 2 October 1951, II. Abt., Handakten Helmut Strebel, Wissenschafliche Korrespondenz, rep. 44, no. 31, vol. 1, Archive of the Max Planck Society.

[13] Letter Helmut Strebel (fn. 12).

[14] Letter from Juraj Andrassy to Helmut Strebel, dated 10 October 1951, II. Abt., Handakten Helmut Strebel, Wissenschafliche Korrespondenz, rep. 44, no. 31, Archive of the Max Planck Society.

[15] Juraj Andrassy, Völkerrechtliche Elemente im jugoslawischen Strafrecht, HJIL 14 (1952), 549–560.

[16] Letters from Helmut Strebel to Juraj Andrassy (fn. 12, 14).

[17] Philipp Glahé, The Heidelberg Circle of Jurists and its Struggle against Allied Jurisdiction: Amnesty-Lobbyism and Impunity-Demands for National Socialist War Criminals (1949–1955), Journal of the History of International Law – Revue d’histoire du droit international 22 (2019), 1–44.

[18] Hans Thalmann, Grundprinzipien des modernen zwischenstaatlichen Nachbarrechts, Zürich: Polygraphischer Verlag 1951.

[19] Juraj Andrassy, Thalmann, Hans: Grundprinzipien des modernen zwIschenstaatliehen Nachbarrechts. Zürich: Polygraphischer Verlag 1951. 175 S. (Zürcher Studien zum Internationalen Recht. Nr. 19), Buchbesprechung (Book Review), HJIL 14 (1952), 578–579.

[20] Juraj Andrassy, Der Balkan-Entente-Pakt von Ankara vom 28. Februar 1953, HJIL 15 (1953/1954), 133–139.

[21] Juraj Andrassy, Betrachtungen über die Zuständigkeit des Internationalen Gerichtshofes, HJIL 19 (1958), 1–23.

[22] Juraj Andrassy, Međunarodno pravosuđe: ustrojstvo i postupak, Zagreb: Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti 1948.

[23] Juraj Andrassy, Zoričić, Milovan: Teritorijalno more s osvrtom na otvoreno i unutarnje more, vanjski pojas i pitanja kontinentalne ravnine. [Das Territorialmeer unter Berücksichtigung der hohen See, der Eigengewässer, der zusätzlichen Zone und der Fragen des Festlandsockels]. Zagreb 1953. 270 S. (Zagreb, Werke der jugoslawischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Band 45), Buchbesprechung (Book Review), HJIL 16 (1955/1956), 127–129.

[24] Juraj Andrassy, Bloomfield, L. M.; Gerald F. Fitzgerald: Boundary Waters Problems of Canada and the United States (The International Joint Commission 1912-1958). Toronto: Carswell 1958. X, 264 S., Buchbesprechung (Book Review), HJIL 20 (1960), 699–700.

[25] Juraj Andrassy, Les progrès techniques et l’extension du plateau continental, HJIL 26 (1966), 698–704.

[26] Juraj Andrassy, Epikontinentalni pojas, Zagreb: JAZU Jadranski institut 1951.

[27] Cf.: Budislav Vukas, Juraj Andrassy o pravu mora, Jugoslovenska revija za međunarodno pravo 26 (1979), 202–203, 206.

Leon Žganec-Brajša is a doctoral candidate and teaching and research assistant at the Department of Public International Law at the University of Zagreb.

Close links with the Institute: Juraj Andrassy and Alexander N. Makarov at the conference “Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit der Gegenwart” in 1961 (Photo: MPIL)

Close links with the Institute: Juraj Andrassy and Alexander N. Makarov at the conference “Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit der Gegenwart” in 1961 (Photo: MPIL)