English

I arrived in Heidelberg along with the dozens and dozens of blue Trabants of those fleeing East Germany via Hungary. Neuenheimer Feld, the area of Heidelberg where the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (MPIL) is located, was full of these cars that, in their precariousness, evoked another world which would soon disappear.

I came to write my doctoral thesis, which my mentors, Professors Vincenzo Atripaldi and Claudio Rossano, wanted to have a strong comparative flavour. Claudio Rossano, in particular, who had spent a lot of time in Heidelberg during his studies, spoke of it as a place where I could study profitably and, at the same time, forge friendships. He recalled the presence of many young colleagues who, together with him, had spent a period of study between the MPIL and the Juristisches Seminar (the law faculty building), including Augusto Barbera, Carlo Amirante, and Alfonso Masucci.

Socialising in the Reading Room

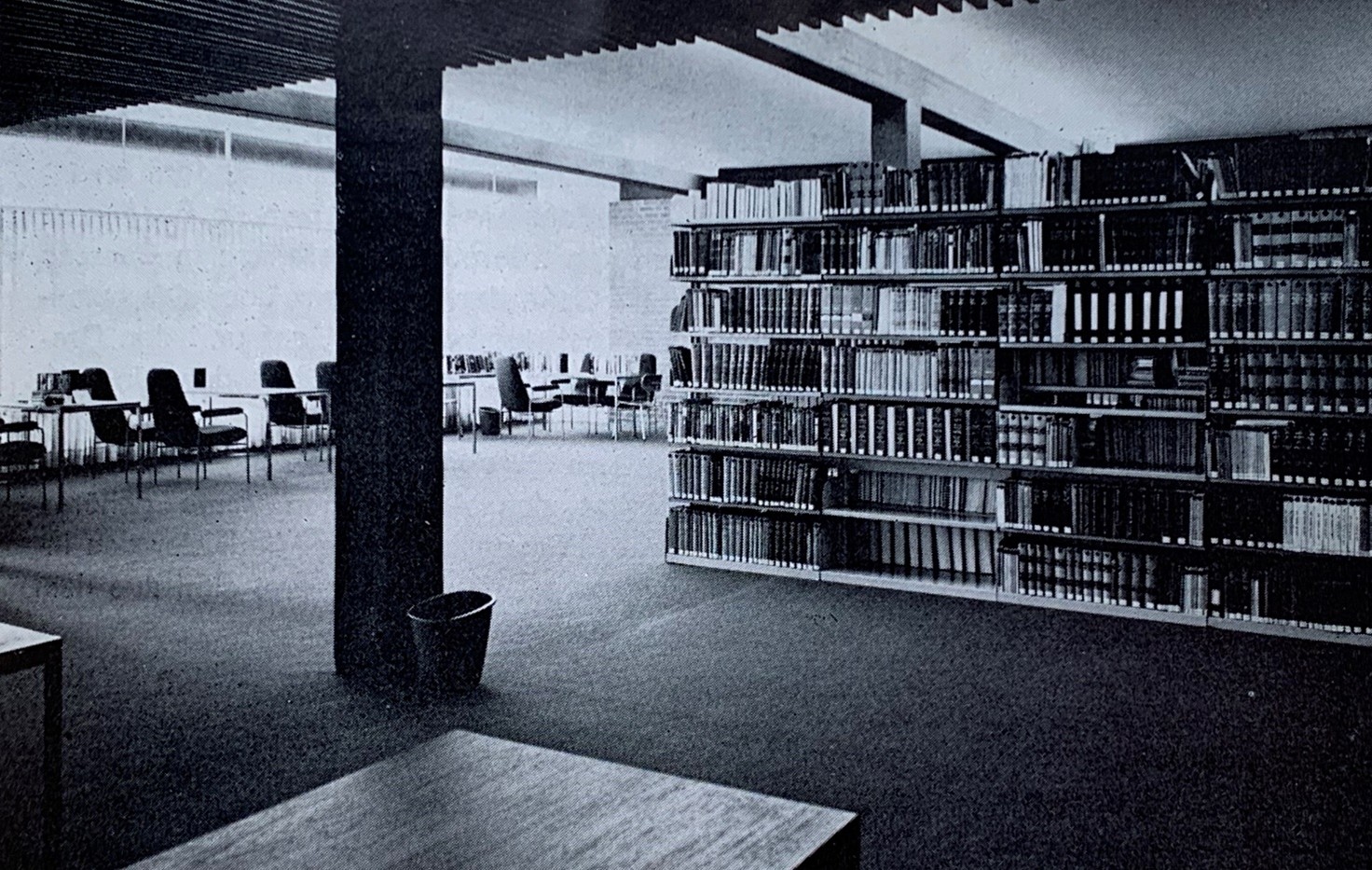

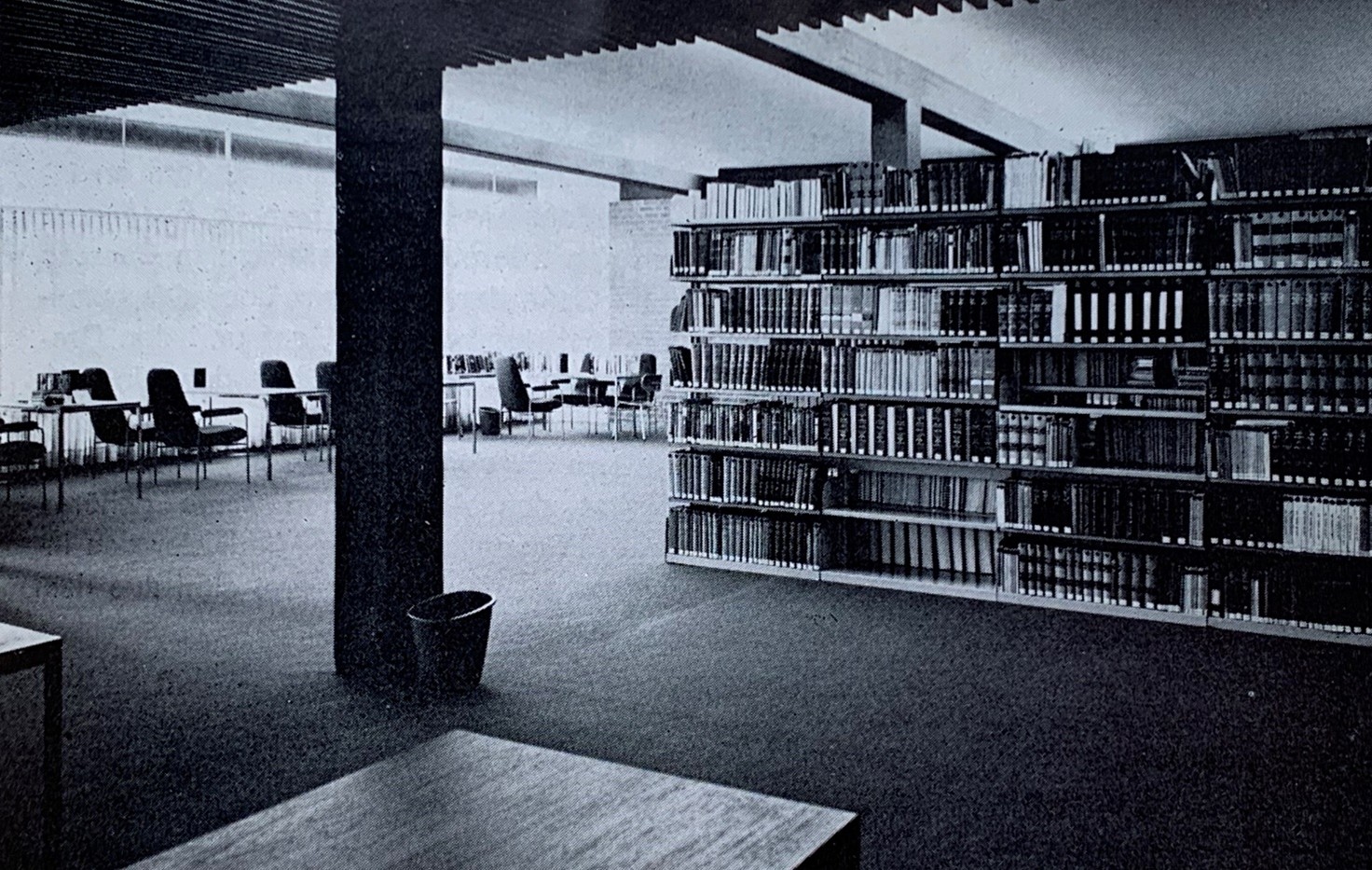

The Institute’s reading room at the Max-Planck-Haus, 1975[1]

It was perhaps because I had just spent six months in Zurich at the Institute of Comparative Constitutional Law, where I did not have the opportunity to meet any peers working on their PhDs, but what struck me from the very beginning of my time at the MPIL was the immediate immersion in an atmosphere of sharing and comparing one’s research activities with other young scholars. There were daily exchanges of opinion on what was happening around us – the fall of the Iron Curtain – and, at the same time, on the research that everyone was carrying out. The atmosphere among us – I mean among those who “inhabited” the Lesesaal (reading room) – was so positive that I decided to stay much longer than the initially planned six months.

At that time, the reading room was frequented mainly by young people from Greece, South Africa, Israel, the former Yugoslavia, and Turkey. There were also many Spaniards and Portuguese. The Germans, who came from nearby universities to complete their doctoral and habilitation theses, could not be overlooked either. There were a few English- and Frenchmen as well. And then there were the Italians, a presence that was not large initially but would soon become perhaps the largest and most constant community. It was there that I met –to name friends and colleagues to whom I am still bound today– Agatino Cariola, Giuseppe Cataldi, Filippo Donati, Pier Francesco Lotito, and Alberto Lucarelli. Typically, Italians stayed for relatively short periods and then immediately returned to Italy.

I decided to stay longer, and this allowed me to consolidate relationships and friendships with many (then) young scholars, who hold important positions in universities and institutions around the world today. Here, again, I would like to mention a few: Iris Canor, Miguel Angel Cabellos Espierrez, Erika de Wet, Petros Mavroidis, Petros Patronos, and José Luis Rodriguez Alvarez.

After some time, the Institute Director I was reporting to, Professor Jochen A. Frowein, invited me to attend the weekly meeting that, at the time, took place every Monday afternoon (the Referentenbesprechung, now Monday Meeting) and involved all the young research fellows. For me, it was an opportunity not only to observe a different way of doing research – more participatory or ‘from below’ than what was happening at Italian universities at the time – but above all to come into contact (and in some cases to make friends) with the many young Germans who chose to do their training at the MPIL. Many of them are now professors at prestigious universities in Germany or involved in European institutions (Michael Hahn, Matthias Hartwig, Georg Nolte, Stefan Oeter, Jörg Polakiewicz, and Andreas Zimmermann).

The Library. An Invaluable Resource

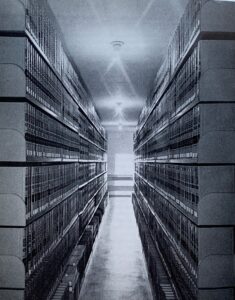

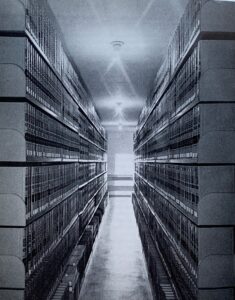

The library stack in 1975[2]

To speak only of the personal and academic relationships which have developed and strengthened over the years would, however, be to omit the main reason why so many young researchers from all over the world came to the Institute. And that reason was, and is, the library. The abundance of the library, which goes back to the Berlin period, is impressive. In this particular case, as I had to write a thesis that had at its roots the study of federal systems, access to the classics of German federalism, and more, was crucial. From that abundance flowed stupendous classics of legal literature on the subject (some written in Gothic letters). What was equally, if not more astonishing, however, was the fact that Italian publicist literature, not only from the 20th century but also from the 19th century, was available as well. I remember the amazement of librarians who wondered (and perhaps still wonder today) why on earth Italians would ask for Italian books. The answer obviously lies in the shortcomings of many Italian university libraries.

I don’t think it exists anymore today, but until the late 1990s, there was a paper index of articles, compiled by subject: A work of exceptional value, today taken over, mostly, by the Internet (and the OPAC system). But at the time, it was a tool of incomparable value for anyone who wanted to conduct research in a new area or refine their knowledge or check something on a particular subject. And not only with regard to German literature, but literature from all over the world.

And now I come to the people who, over the years, have made the library work. I would like to dedicate a thought to the Library Director, Joachim Schwietzke, who, even today, although retired, still makes his experience and profound knowledge of treatise history available to the Institute. But special thanks go to the many other library staff with whom I have come into contact over the years: Marianne Kraft, Ali Zakouri, and Sandra Berg.

A Modernised Institute. The MPIL Since 2002

The new Institute building in 2010[3]

At the turn of the century, the Institute renewed its leadership, first with the arrival of Armin von Bogdandy, who took over as director in 2002, and then with Anne Peters in 2013. My relationship with Armin in particular has become increasingly friendly over time. Precisely for this reason, it is not for me to pass judgement on whether and how the Institute has changed in the last twenty years.

Certainly, from a strictly personal point of view, my view of the Institute has naturally changed. At some point, my sojourns no longer had the exclusive purpose of studying research originating in Italy, but also became an opportunity to become involved in the Institute’s research. The fact that Armin von Bogdandy’s field of scientific interest favoured European constitutional law played a role in this, thus intercepting my study activities more immediately. I am thinking in particular of my involvement in the adventure of the magnum opus that was Jus Publicum Europaeum, coordinated precisely by Armin von Bogdandy, and which gave me the opportunity to enter into communication with many highly estimated foreign colleagues.

Then, there is an objective factor that is obvious when looking at the composition of the research staff from a historical perspective (albeit still related to my personal experience): Whereas up until the late 1990s researchers were mostly German, in the last twenty years the presence of young foreign scholars within the research staff is undoubtedly considerable. To this objective evidence a further notation must be added, concerning, more specifically, the presence of qualified young Italian scholars, whom I have been able to meet personally in recent years. Some have returned to Italian universities, others have found a place in foreign universities, and others have chosen the path of international institutions, bearing witness to the fact that the selection made by the Institute was carried out with an exclusive focus on quality: Davide Paris, Angelo Junior Golia, Sabrina Ragone, Giacomo Rugge, Valentina Volpe. There might be some more I am forgetting.

For my part, I do not miss any opportunity to encourage the young people who work with me to come to the Institute for a brief, or longer, research stay. In this way, relationships are developed between new generations.

Concluding these brief personal recollections, one would like to talk about a Max Planck ‘model’, i.e. a research facility excellence which has always been open to all, where anyone who wants to put themselves to the test is welcomed and enabled to study. A model that has been supported with public funds for a hundred years, a successful example of cooperation between the Bund (federal government) and the Länder (governments of German states). But this would be too complex, and perhaps irritating, for us Italians. The fact is that, like the protagonist of a Heinrich Böll short story, I continue to have the ‘defect’ of returning to Heidelberg whenever I can.

***

[1] Photo: MPIL.

[2] Photo: MPIL.

[3] Photo: MPIL.

Italiano

Sono arrivato ad Heidelberg insieme alle decine e decine di Trabant azzurre che, attraverso l’Ungheria, fuggivano dalla Germania orientale. Neuenheimer Feld, la zona di Heidelberg dove ha sede il Max Planck Institut (MPIL), era piena di queste auto che, nella loro precarietà, evocavano un altro mondo, che di lì a poco sarebbe definitivamente scomparso.

Vi andai per scrivere la tesi di dottorato, che i miei maestri, i professori Vincenzo Atripaldi e Claudio Rossano, vollero avesse una forte impronta comparatistica. Claudio Rossano, in particolare, che aveva trascorso molto tempo ad Heidelberg al tempo della sua formazione, me ne parlò come di un luogo in cui avrei potuto studiare proficuamente e, allo stesso tempo, intessere amicizie. Rievocò la presenza di tanti giovani colleghi che, insieme a lui, avevano trascorso un periodo di studio tra il Max Planck e lo Juristisches Seminar (la facoltà di Giurisprudenza di Heidelberg), tra cui Augusto Barbera, Carlo Amirante, Alfonso Masucci.

La sala di lettura come luogo di socializzazione

La sala di lettura dell’Istituto nella Max-Planck-Haus nel 1975[1]

Fu forse perché arrivavo da sei mesi trascorsi a Zurigo presso l’Istituto di diritto costituzionale comparato, dove non ebbi occasione di conoscere coetanei anch’essi in fase di formazione, ma ciò che mi colpì fin dall’inizio dell’Istituto (intendo ovviamente il Max Planck) fu l’immediata immersione in un’atmosfera di condivisione e di confronto delle proprie attività di ricerca con altri giovani studiosi. Erano quotidiani gli scambi di opinione su quanto stava avvenendo intorno a noi –lo sgretolarsi della cortina di ferro- e, allo stesso tempo, sulle ricerche che ciascuno portava avanti. Il clima che si creò tra di noi -intendo tra quelli che popolavano la Lesesaal, la sala di lettura- fu così positivo che decisi di rimanere ben oltre il periodo di sei mesi inizialmente previsto.

La sala di lettura, in quegli anni, era frequentata soprattutto da giovani provenienti dalla Grecia, dal Sud Africa, da Israele, dalla ex-Jugoslavia, dalla Turchia. Molti anche gli spagnoli e i portoghesi. I tedeschi, che arrivavano dalle Università vicine per portare a termine i loro lavori di dottorato e di abilitazione, costituivano anche una presenza discreta. Pochi gli inglesi e i francesi. E poi vi erano gli italiani, una presenza che all’epoca non era nutrita ma che lo sarebbe divenuta col tempo, tanto da costituire, forse, la comunità più folta e costante. È lì che ho conosciuto -per fare dei nomi di amici e colleghi a cui sono ancora oggi legato- Agatino Cariola, Giuseppe Cataldi, Filippo Donati, Pier Francesco Lotito, Alberto Lucarelli. La caratteristica degli italiani era quella di rimanere per periodi relativamente brevi e poi ritornare subito in Italia.

Io decisi di rimanere più a lungo e ciò mi permise di consolidare rapporti ed amicizie con molti giovani (all’epoca) studiosi, che oggi ricoprono ruoli importanti in università e istituzioni di tutto il mondo. Anche qui ne cito alcuni: Iris Canor, Miguel Angel Cabellos Espierrez, Erika de Wet, Petros Mavroidis, Petros Patronos, José Luis Rodriguez Alvarez.

Dopo qualche tempo, il direttore dell’Istituto a cui facevo riferimento, il prof. Jochen A. Frowein, mi invitò a partecipare alla riunione settimanale che all’epoca si svolgeva ogni lunedì pomeriggio (Referentenbesprechung) e coinvolgeva tutti i giovani referendari. Fu per me l’occasione non solo di osservare un modo diverso di fare ricerca, più partecipato ‘dal basso’, di quanto non accadesse a quell’epoca nelle Università italiane, ma soprattutto di entrare in contatto (e in alcuni casi di stringere amicizia) con i tanti giovani tedeschi che sceglievano di svolgere la loro attività di formazione presso il Max Planck. Molti di loro sono oggi professori in prestigiose università in Germania o impegnati nelle istituzioni europee (Michael Hahn, Matthias Hartwig, Georg Nolte, Stefan Oeter, Jörg Polakiewicz, Andreas Zimmermann).

Di valore ineguagliabile: la biblioteca

Il magazzino della biblioteca[2]

Parlare solo delle relazioni personali e accademiche, che negli anni si sono sviluppate e consolidate, vorrebbe però dire omettere la ragione principale per la quale così tanti giovani ricercatori, proveniente da tutto il mondo, si recavano all’Istituto. E quella ragione era ed è la biblioteca. Il pozzo librario, formatosi a partire dal periodo berlinese, è impressionante. Nel caso specifico, dovendo scrivere una tesi che aveva alle sue radici lo studio dei sistemi federali, l’accesso ai classici del federalismo tedesco, e non solo, era fondamentale. Da quel pozzo emergevano classici stupendi della letteratura giuspubblicistica in argomento (alcuni scritti in lettere gotiche). Ciò che tuttavia era altrettanto, se non più sorprendente, era la possibilità di avere a disposizione anche la letteratura pubblicistica italiana, non solo quella novecentesca ma anche quella ottocentesca. Ricordo lo stupore dei bibliotecari che si chiedevano (e forse ancora oggi si chiedono) perché mai gli italiani chiedessero in consultazione libri italiani. La risposta sta ovviamente nelle carenze di molte biblioteche universitarie italiane.

Oggi non credo esista più, ma fino alla fine degli anni Novanta del secolo scorso esisteva poi uno schedario cartaceo degli articoli, redatto per soggetti. Un’opera di valore eccezionale, oggi in gran parte travolta da internet (e dal sistema Opac). Ma all’epoca era uno strumento di incomparabile valore per chi volesse condurre una ricerca su un soggetto nuovo oppure volesse perfezionare e svolgere gli ultimi controlli su una determinata materia. E non solo con riguardo alla letteratura tedesca ma a quella mondiale.

E vengo ora alle persone che, negli anni, hanno fatto funzionare la biblioteca. Mi piace dedicare un pensiero al direttore della biblioteca, Joachim Schwietzke, che ancora oggi, per quanto in pensione, mette a disposizione dell’Istituto la sua esperienza e la sua profonda conoscenza della storia dei trattati. Ma un ringraziamento particolare va ai tanti altri addetti alla biblioteca con i quali sono venuto a contatto negli anni: Marianne Kraft, Ali Zakouri, Sandra Berg.

Un istituto rinnovato. Il MPIL dal 2002

Il nuovo edificio dell’Istituto nel 2010[3]

A cavaliere del secolo l’Istituto ha rinnovato i propri vertici, prima con l’arrivo di Armin von Bogdandy, insediatosi come direttore nel 2002 e poi con Anne Peters nel 2013. Con Armin il rapporto è divenuto, col passare del tempo, sempre più amicale. Proprio per questo non sta a me esprimere un giudizio sul come e sul se l’Istituto sia cambiato negli ultimi vent’anni.

Certo è che, da un punto di vista strettamente personale, anche il mio sguardo sull’Istituto è naturalmente cambiato. A partire da un certo momento, i miei soggiorni non sono stati solo di studio per ricerche che nascevano in Italia ma sono divenuti anche occasione di coinvolgimento nelle ricerche dell’Istituto. In ciò ha giocato un ruolo la circostanza che il campo di interesse scientifico di Armin von Bogdandy abbia privilegiato il diritto costituzionale europeo, intercettando così più immediatamente le mie attività di studio. Penso in particolare al coinvolgimento nell’avventura di quell’opus magnum che è stato Jus Publicum Europaeum, coordinato appunto da Armin von Bogdandy, e che mi ha dato l’occasione di entrare in comunicazione con molti colleghi stranieri di grande valore.

Vi è poi un fattore oggettivo che emerge non appena si guardi alla composizione del personale di ricerca in una prospettiva storica (per quanto sempre legata alla mia personale esperienza). Mentre fino alla fine degli anni Novanta del secolo scorso i ricercatori erano per lo più tedeschi, negli ultimi venti anni la presenza di giovani studiosi stranieri, all’interno del personale di ricerca (Mitarbeiter), è senz’altro notevole. A questa evidenza oggettiva va aggiunta una ulteriore notazione, riguardante, più in particolare, la presenza di qualificati giovani studiosi italiani, che negli ultimi anni ho potuto conoscere personalmente. Alcuni sono ritornati in Università italiane, altri hanno trovato spazio in Università straniere, altri hanno scelto la strada delle istituzioni internazionali, a testimonianza che la selezione fatta dall’Istituto è stata svolta guardando esclusivamente alla qualità: Davide Paris, Angelo Junior Golia, Sabrina Ragone, Giacomo Rugge, Valentina Volpe. E forse ne dimentico qualcuno.

Per parte mia, non perdo l’occasione di spronare i giovani che collaborano con me a svolgere periodi più o meno lunghi di studio presso l’Istituto. Si sviluppano così rapporti tra nuove generazioni.

Concludendo questi brevi ricordi personali, verrebbe voglia di parlare di un ‘modello’ Max Planck, e cioè di una struttura di ricerca di eccellenza, aperta da sempre a tutti, in cui chiunque voglia mettersi alla prova viene accolto e messo in condizione di studiare. Un modello che da cento anni viene sostenuto con fondi pubblici, esempio riuscito di cooperazione tra Bund e Länder. Ma questo sarebbe un discorso troppo complesso e forse irritante per noi italiani. Sta di fatto che, come il protagonista di un racconto di Heinrich Böll, continuo ad avere il ‘difetto’ di tornare ad Heidelberg quando posso.

***

Raffaele Bifulco is a Professor of Constitutional Law at the LUISS Guido Carli University of Rome.

The main entrance of the former Institute’s building in Berliner Strasse in 1975 (Photo: MPIL)

The main entrance of the former Institute’s building in Berliner Strasse in 1975 (Photo: MPIL)