The close ties between the Max Planck Society and the Israeli scientific community, especially the Weizmann Institute of Science, go back to the 1950s, not long after the Holocaust.[1] They include the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (MPIL), as I discovered as a law student at Tel Aviv University (TAU).

In the mid-1980s, a small announcement appeared on the TAU “blackboard” stating that the law faculty was looking for students for a course on “European Community Law” to be taught by Professor Joseph Weiler (then of the University of Michigan Law School). A curious “trophy” was promised: of the students who successfully completed the course, a few would be selected to participate in a delegation to the Max Planck Institutes. None of the students really knew what these were. In the summer of 1987, the first delegation of about a dozen Israeli students and two professors came for a two-week visit, first to the Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law in Hamburg, followed by a one-week visit to the MPIL in Heidelberg. A year later, I was part of the second delegation, which was the only one to also visit the Max Planck Institute for International and Comparative Criminal Law in Freiburg.

Long associated with the Institute. Joseph Weiler at the Masterclass “How to Read Decisions of the European Court of Justice?“ in Heidelberg, 2017[2]

The seminars were structured as a series of lectures on German private law and European and German public law. Each lecture consisted of a lengthy introductory presentation by a German scholar to familiarise the Israeli students with German law, followed by a comparative section in which the Israeli students provided input. It was an important learning experience for the Israeli students to encounter the civil law approach. Comparisons between Israel’s predominantly common law system (which was in the process of transforming into a mixed system) and the continental civil law tradition, as well as debates on certain aspects of legal theory and interdisciplinarity, unfolded. The importance of these links was reflected by the fact that the Directors (Ernst-Joachim Mestmäcker in Hamburg and Jochen Abr. Frowein in Heidelberg) opened with keynote speeches and a welcome reception in their private homes. A telling anecdote can be mentioned: One of the things the Israeli delegation did in Heidelberg was to listen to the famous Referentenbesprechung (now known as the Monday Meeting today). The Institute made an exception by holding the meeting in English rather than the usual German. Years later, in light of the increasing number of international visiting scholars, this exception was extended so that the Monday meetings alternated between English and German. In retrospect, the exception I described could hence be seen as the Israeli delegation’s contribution to the internationalisation of the MPIL.

Close ties between the Max Planck Society and Israel. Otto Hahn, the President of the MPG, on his way to the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot in 1959 (with Feodor Lynen, Wolfgang Gentner, Alice Gentner, and Josef Cohn)[3]

It became a tradition for delegations from both Max Planck institutes to come to the TAU Law Faculty in the following winter semester to participate in seminars with their counterparts. This tradition of reciprocal visits continued for several years, with some variations, first annually and then every two years. At a certain point, the visits of the German academics stopped. Eventually, the Israeli student delegations also came to an end, mainly because the funding was cut.

These academic trips provided an important link between scholars from the two legal systems. Many Israeli scholars came for research stays at the Max Planck Institutes, and many German scholars participated in conferences at the TAU Law Faculty or came as visiting professors. Moreover, it was one of the rare instances in which research institutes made direct contact with students, and not just with academics. For us students, it was an eye-opener to realise that law is not only a profession, but also an academic field where researchers carry out in-depth analytical studies of abstract legal issues, for which the library is the laboratory. It also showed us the importance of comparative law. Moreover, for many Israeli students it was the first time (similar to the idea behind the EU’s Erasmus programme) that we left Israel professionally, talked about legal issues in English, realised that legal problems cross borders, met foreign (German) researchers and got to know their interests, culture, and hobbies. Many made lasting personal connections (long before social media) and continued to write letters and to visit each other on private trips. At a time when many Holocaust survivors were ambivalent about even visiting Germany, this was an important bridging experience.

The Trubowicz Building of Law, which houses the Tel Aviv University Faculty of Law[4]

Indeed, cooperation between the MPIL and Israeli law faculties has flourished. A director of the MPIL – Professor Frowein – and researchers were involved in the Hukah Le’Israel (A Constitution for Israel) project, a movement to draft a constitution for Israel based on the experience of comparative law. The project ultimately failed, but it was successful intellectually. In addition, the strong German influence left its mark on a parallel attempt to change the Israeli electoral system and introduce direct election of the prime minister (which was introduced into the Israeli legal system for three electoral terms but was subsequently abolished). Cooperation has deepened with the establishment of two Minerva Centres for the Protection of Human Rights at the Hebrew University and TAU, supervised by the directors of the MPIL.

At the MPIL, there has always been a deep interest in the Israeli legal system. Over the years, there was always a researcher responsible for reporting on Israeli legal developments. Israel was often discussed either from the perspective of international law (for example, the Oslo Accords and later the Second Lebanon War) or from the perspective of constitutional law (the 1990s was the time when Israel underwent its “constitutional revolution”, enacting basic laws dealing with human rights and entrenching them by borrowing the German principle of proportionality and the possibility of judicial review).

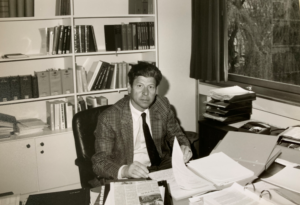

Jochen Abr. Frowein in his office at the Institute, 1985[5]

Personally, being part of the student delegation to MPIL was a life-changing experience. Unlike many of my friends from university who chose to continue their studies at the best universities in the US, I was one of the very few Israeli students to complete my PhD in Germany while on a scholarship from the MPIL. After completing my LL.B. at TAU and my military service in the Legal Department of the Israel Defence Forces, I studied for an LL.M. at the College of Europe in Bruges, Belgium. The supervisor of my master’s thesis, Professor Jörn Pipkorn of the Legal Service of the European Commission recommended that I contact his friend Jochen Frowein for a PhD. The name sounded familiar. Professor Frowein not only agreed that I could work on my dissertation at the Institute but also helped me to obtain a Minerva scholarship (the first to be awarded to a law student), which made my stay financially easier. Choosing Europe, I decided to become a scholar of European Union law. I received my PhD from the Europa-Institut at the University of Saarland, Germany (my PhD supervisors were Professor Stein and Professor Ress, both MPIL alumni).

Although I returned to Israel and joined the academic world, I never really left the MPIL. I returned on almost every academic leave to continue my research in European law, benefiting from the invaluable brainstorming with the brilliant scholars and from the amazing library. I climbed the academic ladder in Israel and also became an honorary professor at the Europa-Institut in Saarbrücken and a senior research affiliate at the MPIL. Most importantly, I made friends with academics in Germany and around the world who have at some point passed through the MPIL. I feel deeply indebted to the MPIL, which became my academic home.

[1] On the development on relations with the Weizmann Institute see: Carola Sachse (ed.), Wissenschaft und Diplomatie: die Max-Planck-Gesellschaft im Feld der internationalen Politik (1945–2000), Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2023, 70 – 107; English edition forthcoming.

[2] Photo: MPIL.

[3] Photo: APMG.

[4] Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

[5] Photo: MPIL.

Professor Iris Canor is a member of the Faculty of Law at Zefat Academic College and the Striks School of Law at the College of Management Academic Studies in Israel, and a Senior Research Affiliate at MPIL. She also teaches as an adjunct professor at the Law Faculty of the University of Saarland and at the Law Faculties of Tel-Aviv University and Bar Ilan University.

The Institute building in Berliner Straße, 1971 (Photo: AMPG)

The Institute building in Berliner Straße, 1971 (Photo: AMPG)

Pingback: Impressions of an Italian traveller. The Institute in the Course of Time – MPIL100